Erotic Imagination

When Lequeu’s drawings entered the Royal Library, twenty-seven sheets with “lascivious and obscene” subjects were relegated to the restricted access division, later dubbed Hell (L’Enfer). Born in an era that celebrated libertinism, investigations of sexuality, and antiquities with erotic subjects, Lequeu created works ranging from explicit anatomical studies to suggestive juxtapositions of flesh and stone.

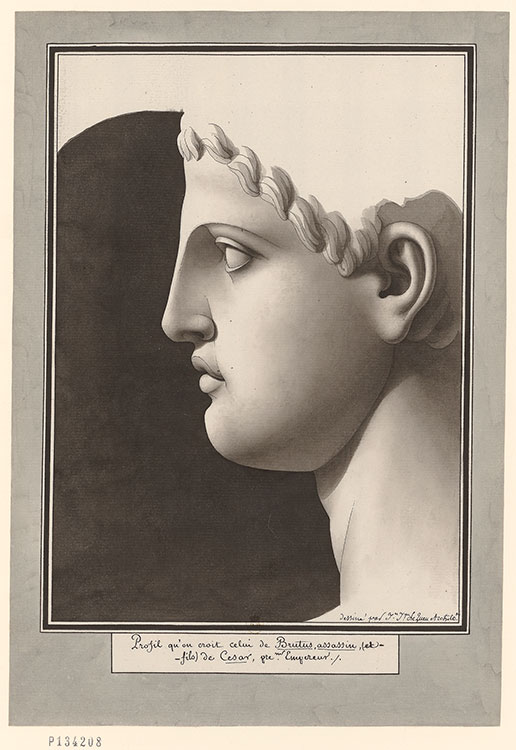

Brutus, the Assassin and Son of Caesar

This sculptural profile drawing depicts Brutus, whom Lequeu’s inscription describes in terms of his role in the assassination of his adopted father Julius Caesar. Identified by Lequeu as the “first emperor,” Caesar was proclaimed dictator for life in February of 44 BCE but was murdered soon after by senators who felt such a move threatened the the Roman republic. Revolutionaries in France celebrated Brutus as a virtuous republican who put his convictions in support of the state ahead of his love for his father.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Brutus, the Assassin and Son of Caesar, ca. 1792

Pen and black ink, black and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

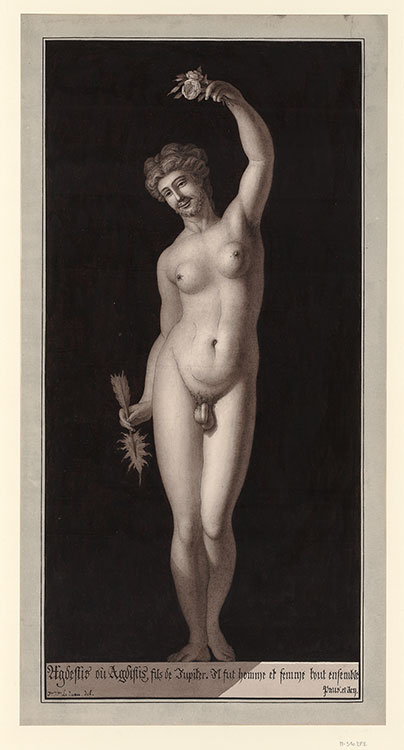

Agdistis, Son of Jupiter

Lequeu was intrigued by the concept of gender fluidity. His interest led him to depict a rarely discussed figure from a 1727 mythological dictionary: Agdistis, born of the gods Jupiter and Cybele, who had both male and female physical attribut es and was castrated by the gods. Lequeu showed the young deity frontally, with breasts and male genitalia. The figure holds a rose and an arrow-shaped lightning bolt, alluding to the female and male sexual organs.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Agdistis, Son of Jupiter, ca. 1794–95

Pen and black ink, black and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

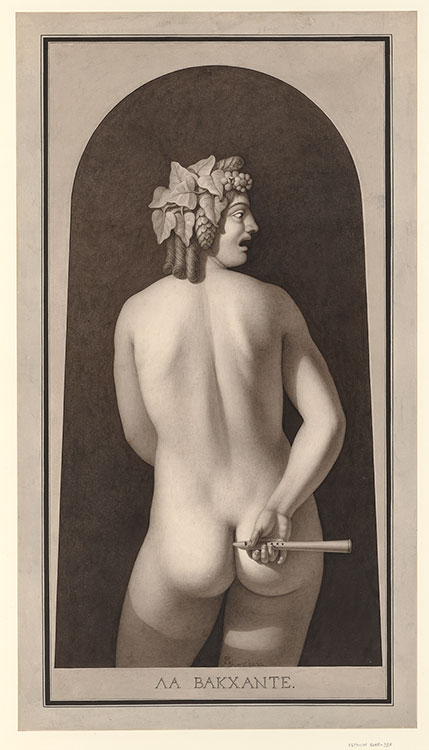

The Bacchante

Lequeu’s explorations of amorous themes are often amusing. Seen from behind, a woman wearing an ivy wreath positions an aulos, a wind instrument used during feasts, suggestively near her backside. An inscription in Greek identifies her as one of the bacchantes, female companions of Bacchus, the god of wine, who indulged in frenzied trances while possessed by the wild power of nature. Her face, seen in profile, resembles a theatrical mask—a reminder that classical stage performances originated in bacchic rituals.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

The Bacchante, ca. 1798

Pen and black ink, black and gray-brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

He Is Free

This curious scene considers the association between liberation and libertine architecture. A nude woman, lying on her back in a gravity-defying pose, extends her upper body from a niche to free a male lyrebird; the first specimens of this bird, native to Australia, had just reached Europe. Below the niche, four melancholy masks frame the title. The contrast between the woman’s soft, curved body and the sharp, rigid stone surround produces an erotic tension.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

He Is Free, 1798–99

Pen and black ink, brown and red wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

What She Sees in a Dream

Here, Lequeu visualized a young woman experiencing an erotic dream. She lies asleep on a sofa above an elaborate alcove housing a peacock and baskets with fruits and flowers. Other imagery evoking male genitalia, including arrows, acanthus shoots, and a winged cupid riding a phallus, surrounds her.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

What She Sees in a Dream, 1794–95

Pen and black ink, brown and black wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Alcove Window

Voyeurism, a motif throughout Lequeu’s designs, is explored explicitly in this nude. Through the bull’s-eye window of an alcove, the viewer gazes at a turbaned woman, eyes downcast and unaware of an observer’s presence, as she holds a mirror. The pointed ornament surrounding the opening is echoed in the antique-like relief on the mirror, which depicts a cupid holding a mirror decorated with a standing figure. This infinitely recurring effect visualizes voyeurism as an insatiable quest that both tantalizes beholders and separates them from the objects of their desire.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Alcove Window, 1797–98

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

The White Savage

Lequeu’s provocatively titled, objectifying study of female buttocks combines near-clinical accuracy with pornographic intent. He labeled parts of the body (“the anus,” “the rump”) while commenting on the physical attributes of his model (“well-formed buttocks,” “firm thighs”). This type of sheet, drawn from life, might have been created in sessions like the one Lequeu described in a 1795 account of his whereabouts during a royalist uprising: “At nine o’clock the citizens Anne-Marie- Catherine Remy and Françoise Thouvenin . . . came to my place to model [and] I occupied myself by drawing several attitudes until three in the afternoon.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

The White Savage, ca. 1795

Pen and black ink, gray and brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Tavern and Hammock of Love, from Civil Architecture

Lequeu’s design for a guinguette, a tavern devoted to eating, drinking, and cabaret performances, is ornamented with tableware, bottles, and wheels of cheese and has columns shaped like wine barrels. The theme of earthly delights is developed in the plan at right for a hammock inside a lush garden that contains flowers producing the “odor of paradise.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Tavern and Hammock of Love, from

Civil Architecture, ca. 1810

Pen and black ink, gray and brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

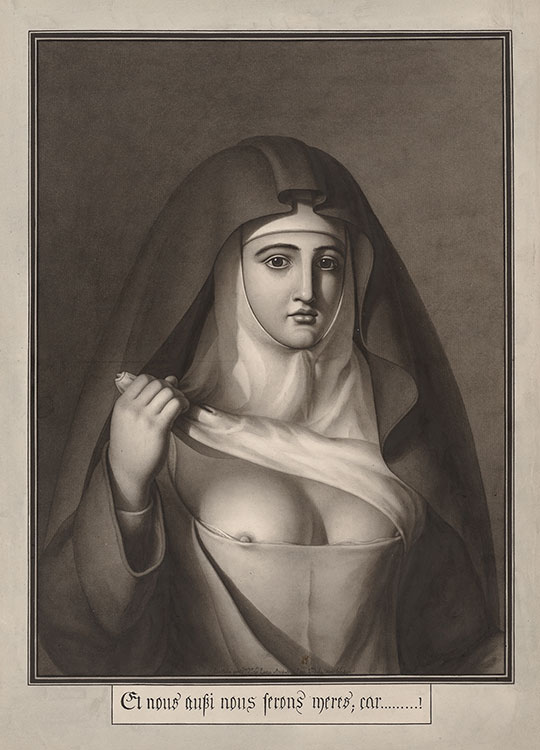

And We Shall be Mothers Because…!

The meaning of this transgressive image of a nun baring her breasts is ambiguous. Lequeu’s cryptic caption may allude to the suppression of the religious orders in 1792, when such institutions were condemned as bastions of social oppression. Such anticlericalism contributed to dechristianizing practices under the Reign of Terror, including mass executions of clergy and coerced marriages. The gesture of stripping off age-old habits and devoting oneself to procreation corresponds with the revolutionary goal of reinventing society, a sentiment echoed in Denis Diderot’s novel Memoirs of a Nun (published posthumously in 1796).

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

And We Shall be Mothers Because . . . !, 1793–94

Pen and black ink, black and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie