Revolutionary Ambitions

The French Revolution heralded commissions for patriotic monuments commemorating the newly established republic. In 1794, Lequeu submitted five designs to competitions for major civic projects. Although some of his proposals were publicly exhibited, none were selected to be built.

Lequeu embraced revolutionary iconography and became a member of the National Guard and the Popular and Republican Society of the Arts, a patriotic assembly that espoused the ideology of the Reign of Terror. His precise political beliefs, however, are difficult to discern. Lequeu’s designs for projects celebrating revolutionary ideals are rich in detail but also humorous and occasionally ironic.

Symbolic Order for a State Room of a National Palace

Emblematic of the ancien régime, the aristocrat was a subject of scorn during the revolution, when many nobles fled France under the threat of the guillotine. Lequeu’s design for a column comprising an aristocrat with shackled wrists punishes the former ruling class in effigy: the noble, denied liberty, is forced to support the weight of the building. This overtly political design

testifies to Lequeu’s active production of revolutionary iconography.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Symbolic Order for the State Room of a National Palace, 1789

Pen and black ink, gray-brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Tomb of Isocrates, Athenian Orator

Turning to another ancient source—Plutarch’s Lives of the Ten Orators—Lequeu transcribed a description of the rhetorician Isocrates’s tomb and rendered a fantastic vision of its appearance. While the original tomb was surmounted by a column bearing a mermaid, symbolizing Isocrates’s eloquence, a mistranslation of the original Greek led Lequeu to include a sheep as the base.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Tomb of Isocrates, Athenian Orator, 1789

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

The Gate of Parisis, from Civil Architecture

This proposal for a monumental entrance gate honoring the Celtic tribe that gave Paris its name was exhibited in the Hall of Liberty shortly before the Reign of Terror ended in 1794. It is dense with republican imagery. Atop an arch, a colossal figure of the Gallic Hercules wears a Phrygian cap, surmounted by a Gallic rooster, as he holds a statue of Liberty standing on a globe. Yet Lequeu’s apparent support for the revolution cannot be taken at face value. On the back of the drawing, he wrote, “A drawing to save me from the guillotine. Everything for the fatherland.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

The Gate of Parisis, from Civil Architecture, 1794

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Aqueduct Transporting Water to the Holy City, from Civil Architecture

This imaginary aqueduct was meant to provide the “most limpid virgin pure water to the Sacred City.” At left is a Tower of Liberty and at right a “republican road,” and beneath the arcade are paths for pedestrians and carriages. The tower is embellished with symbols of independence and liberation. At left, in a diagram of the cornice, the artist calls for decorating the frieze with cat’s heads; the feline was Lequeu’s favorite avatar

of freedom.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Aqueduct Transporting Water to the Holy City, from Civil Architecture, ca. 1800–1804

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Monument to the Glory of Illustrious Men, for the Place de la Victoire, from Civil Architecture

In year II of the republican calendar (1793–94), a competition was held to design a monument commemorating those who had died on 10 August 1792 while storming the Tuileries Palace to depose the king. Lequeu witnessed the celebrations organized in their honor, and some of his marginal inscriptions on this entry are copied from the ephemeral monument erected outside the ruined palace at that time. Even though Lequeu’s design was exhibited in the Hall of Liberty—the assembly room of the Revolutionary Tribunal at the Conciergerie prison—the project was abandoned after Maximilien Robespierre’s dramatic fall from power in July 1794.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Monument to the Glory of Illustrious Men, for the Place de la Victoire, from Civil Architecture, 1794

Pen and black ink, gray-blue wash, pen and red ink, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: For most of the 18th century, French artists enjoyed the patronage of the king and the aristocracy, but these sources of support were dramatically affected by the Revolution when the king was executed, along with many of the aristocrats who hadn't already fled France. Some artists took sides in the political upheaval, such as the painter Jacques-Louis David, whose friendship with Robespierre eventually landed him in prison. Others saw their careers founder or flourished, based on their allegiance. Many who were closely associated with the Ancien Régime left Paris to find work abroad. Remarkably, Lequeu navigated the changing cultural landscape, having only briefly worked with private aristocratic patrons before the Revolution. After a period of insecurity, he focused his energy on teaching, while participating in revolutionary competitions and securing a position with the new government's land registry office. The rest of his mature career unfolded under Napoleon's leadership. This made him part of the new order, which lasted until Napoleon's final downfall at Waterloo in 1815. Lequeu was forced into retirement that year, which marked the return of the monarchy and the start of the Bourbon Restoration. This design for a monument celebrating the martyrs of the Revolution shows Lequeu rallying to the revolutionary cause. But is this from professional expediency, or a reflection of his personal, political sympathies? On the verso, the artist scrawled a comment referring to the 1790s as "the time when human victims were sacrificed to liberty". And on the back of a design for a city gate displayed nearby, he claimed that it "saved me from the guillotine". These remarks, even if in jest, reveal a keen awareness that art and politics could be a matter of life and death.

Etruscan Labyrinth

Intrigued by subterranean labyrinths, Lequeu here envisaged the legendary tomb of the Etruscan king Lars Porsena said to have been built around 500 BCE in Chiusi, Italy. Erected above an inescapable labyrinth, the massive structure boasted tiers of pyramids surmounted by a globe and adorned with bells that sounded in the wind. The scale of the monument is evident from the miniscule figures beneath the trees. At upper left is a rendering of a Roman coin struck in Spain; Lequeu interpreted its design as the mythical labyrinth of the Cretan king Minos. At right, Lequeu provided a compendium of ancient labyrinths based on descriptions from Herodotus and Pliny as well as contemporary travel literature.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Etruscan Labyrinth, 1792

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, patch with revision at base of monument

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Design for a Temple of the Earth, from Civil Architecture

Intrigued by celestial and terrestrial globes, Lequeu frequently employed spheres in his designs. This example reinvents the artist’s Temple of Equality (displayed nearby) but takes the earth as its subject. At center would be a “magnificent spectacle of a planetary model . . . Surrounded by the dome’s representation of the celestial firmament.” Lequeu initially submitted the design to the revolutionary authorities in 1794, but his proposal was unsuccessful. In 1819–20, under the Restoration, he recycled the plan for a competition to design a chapel dedicated to St. Louis in Père-Lachaise Cemetery. After it was rejected again, Lequeu included the drawing in his Civil Architecture as a Temple of the Earth.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for a Temple of the Earth, from Civil Architecture, 1794

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Proposal for the Completion of the Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, from Civil Architecture

Following his victory at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, Napoleon decided to build a monument to the glory of his Grande Armée. The Arc de Triomphe was erected up to the level of the vaults by Jean-François-Thérèse Chalgrin, but construction slowed when he died in 1811. Lequeu’s subsequent proposal sought a solution for the design during the intermediary period before the project resumed in 1823. He transformed the two piers into separate military towers, one on the left for soldiers of the newly restored Louis XVIII’s army and the other for the commanding generals and officers, with a monumental statue of the king situated in between.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Proposal for the Completion of the Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, from Civil Architecture, 1815–23

Pen and black ink, brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Design for an Assembly Hall

The revolutionary constitution ratified 24 June 1793 (year I) established Primary Assemblies, each comprising between two hundred and six hundred citizens who would gather to vote, although this process was never implemented. Among the welter of architectural competitions in 1794 was one to

commemorate the constitution with a space for these assemblies. In his proposal for an assembly hall, Lequeu transformed Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières’s Paris Corn Exchange (1763–69) into a grand arena, circular in plan, capped with a soaring dome, and illuminated by an oculus.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for an Assembly Hall, 1794

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

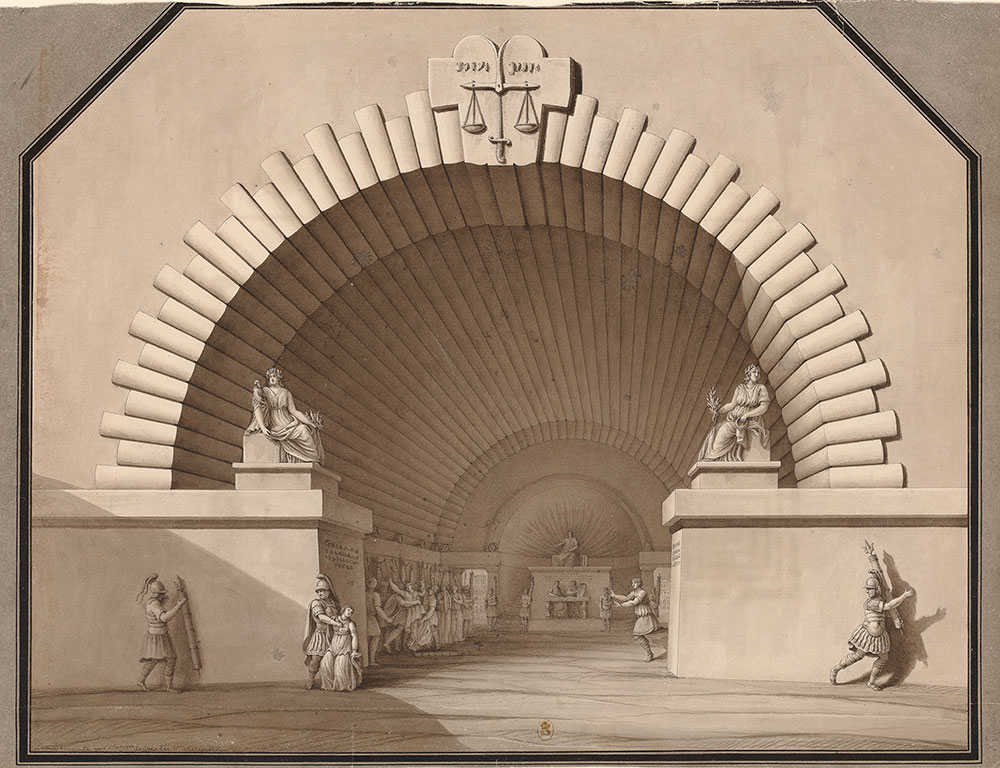

Scene from the Tragedy of Virginia

This design for a theater set was inspired by a 1793 edition of the play Virginie by Jean-François de La Harpe (1739–1803), a passage from which Lequeu copied on the verso of the sheet. As recounted by the ancient writer Livy in his history of Rome, Virginia’s father stabbed her to death to prevent her capture by the lustful Appius Claudius, who claimed she was a fugitive slave from his own estate. Her murder inspired Roman plebeians to revolt against a patrician tribunal. The revolutionary overtones of the subject undoubtedly appealed to Lequeu, who set the tragic action at left in front of a grand vaulted space reminiscent of the cloaca maxima—the Roman sewer—which underscores the theme of the decay of justice.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Scene from the Tragedy of Virginia, 1794–95

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Apotheosis of Trajan

This scene envisages a Roman ceremony marking the deification of the deceased Emperor Trajan in 117 CE. It shows a colossal burning pyre surmounted by a wax effigy of the emperor being kissed by his successor. Lequeu turned to contemporary sources for details as he envisioned the ancient ritual.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Apotheosis of Trajan, after 1802 (inscribed 1794)

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: At the time of his death, Lequeu owned an impressive library containing over 240 titles. The posthumous inventory of his apartment includes a list of books that comprise an intellectual portrait of the artist. His regular and intensive use of these sources is reflected in the copious writings on his drawings. One thing is evident, he was a bookworm. If we imagine ourselves in his studio among the bindings, we would find many classic works on architecture from tomes by the ancient Roman Vitruvius to the Italian Renaissance master, Andrea Palladio. He also own standard texts by contemporary French architects, such as Jean-François Blondel. Reflecting his polymath curiosity, he amassed volumes devoted to chemistry, mathematics, gardening, and the antiquities of Herculaneum. An avid reader of literature as well, he had editions of Michel de Montaigne's introspective essays, Jean de Lafontaine's amusing fables, and an 1804 French edition of the illustrated erotic masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance, The Dream of Poliphilo by Vittorio Colonna. Lequeu also had access to a number of reference works and encyclopedias, and he was familiar with the many volumes of Diderot and d'Alembert's famous Encyclopédie. He was not shy about cracking open the binding on more scandalous titles, including Richard Payne Knight's illustrated exploration of The Ancient Cult of Priapus, the God of Fertility. All of these works helped fuel Lequeu's remarkable creations on paper and continue to inspire a sense of kinship with those whose imaginations are spurred by a good book.

Design for a Temple of Equality

Lequeu prepared this design for a temple in the former aristocratic garden adjacent to the Paris mansion of banker Nicolas Beaujon (now the Élysée Palace) in 1794. He had joined the Popular and Republican Society of the Arts that year, and members were required to demonstrate a refined form of patriotism—likely the reason Lequeu dedicated the temple to Equality. Lequeu adapted the spherical structure from a model popularized by Antoine Laurent Thomas Vaudoyer’s 1782 design for a globular house.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for a Temple of Equality, 1794

Pen and black ink, gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Proposal for an Arch Celebrating the Treaty of Amiens, from Civil Architecture

The Treaty of Amiens, signed by England and France in 1802, created a peaceful interlude during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. A subsequent decree called for proposals for public art to commemorate the truce; the submitted designs would be exhibited for a month in the Gallery of Apollo at the Louvre. In Lequeu’s response, the Ionic capitals in the tower at left are embedded with hearts and rooster heads evoking the fighting cock of Rhodes, an animal celebrated by the ancients for its spirit and a symbol of courage and valor for the victorious French.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Proposal for an Arch Celebrating the Treaty of Amiens, from Civil Architecture, 1802–3

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie