An Architect in Practice and on Paper

After training at the Rouen Public School of Design, in 1779 Lequeu moved to Paris. He found work with the architect Jacques Germain Soufflot, an endeavor that came to an end with the master’s death the following year. He continued to work with Soufflot’s nephew François, overseeing construction at the Hôtel de Montholon. Before the revolution, Lequeu also pursued private patronage.

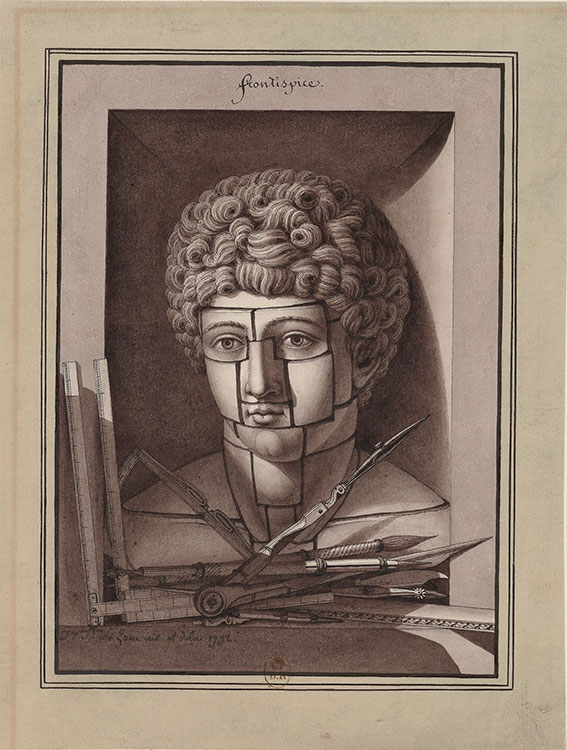

In 1792, Lequeu prepared a series of didactic studies to investigate the structural principles behind drawing the human head. The frontispiece to his New Method Applied to the Elementary Principles of Drawing, Tending to Graphically Perfect the Outline of the Human Head by Means of Various Geometric Figures announces his ambition to decipher antique ideals of beauty using modern tools and geometry.

Lequeu’s principal collection of drawings, grouped under the title Civil Architecture, was conceived originally as a textbook for the practice of architectural draftsmanship. It soon became a repository for a stunning range of designs that, unconstrained by the practicalities of construction, combined elements of humor, memory, and fantasy, often with extensive annotations. While Lequeu prepared the basic instructional drawings at the outset of his career, he continued adding to the collection for the rest of his life.

Draftsman’s Tools, from Civil Architecture

This sheet presents the draftsman’s arsenal: brushes, penholders, graphite, rulers, ruling pens, and erasers. In the accompanying text, Lequeu described his drawing process as a series of stages, beginning with contour lines and following with the addition of light and shadow. He was deeply conscious of the diverse sources of his materials, which, as his annotations indicate, came from as far as China, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Siam (now Thailand).

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Draftsman’s Tools, from Civil Architecture, 1782

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

The Principle of Shadows, frontispiece to the Civil Architecture

In the 107 drawings that comprise his Civil Architecture, Lequeu offered methods for depicting three-dimensional forms, the architectures “of various peoples scattered on the Earth,” and his own inventions. He paid special attention to “shadows and their different effects projected on plans, elevations and profiles by the sunlight or burning bodies,” which was the subject of

a larger debate among contemporary architects.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

The Principle of Shadows, frontispiece to Civil Architecture, 1782

Pen and black ink, gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Funerary monument, from Civil Architecture

Through an agglomeration of architectural decoration, Lequeu transformed a Corinthian column into a funerary monument. Reminders of death and ancient sepulchral rituals abound: a ceremonial urn atop the column; an ancient tear vessel, or lachrymatory, below; and a skull in the pediment above a ceremonial torch. He even incorporated pairs of crossed tibias in the coffered decoration of the cornice seen in the plan at lower left. Most striking, however, is that a large part of the page is dominated not by the monument but by its shadow, which forms a shape that is both strange and ominous.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Funerary Monument, from Civil Architecture

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

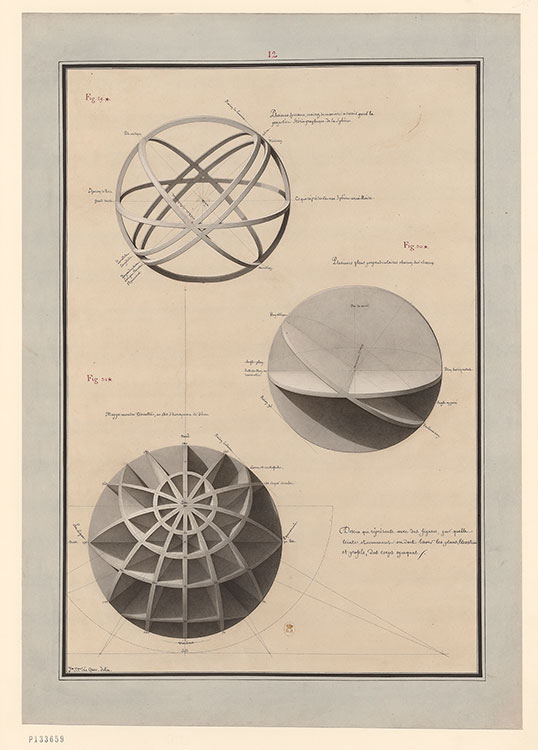

Study of Spheres, from Civil Architecture

Civil Architecture includes a number of didactic sheets outlining visual models for technical draftsmanship. This page offers instructions for creating volume and using light and shadow to define complex three-dimensional objects, like armillary spheres and terrestrial globes. The caption at bottom, “Globe of the Earth, or a framework of a dome,” reflects the wide range of subjects encompassed by Lequeu’s guidelines.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Study of Spheres, from Civil Architecture,

Pen and black ink, gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Frontispiece to the New Method

Lequeu used drawing to interrogate the ancient canon of beauty, epitomized in this sheet by a venerated Roman marble bust thought to represent ideal human proportions. He divided the head into its component parts as if it comprised masonry blocks; beneath, he placed an array of the draftsman’s tools.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Frontispiece to New Method, 1792

Pen and black ink, gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

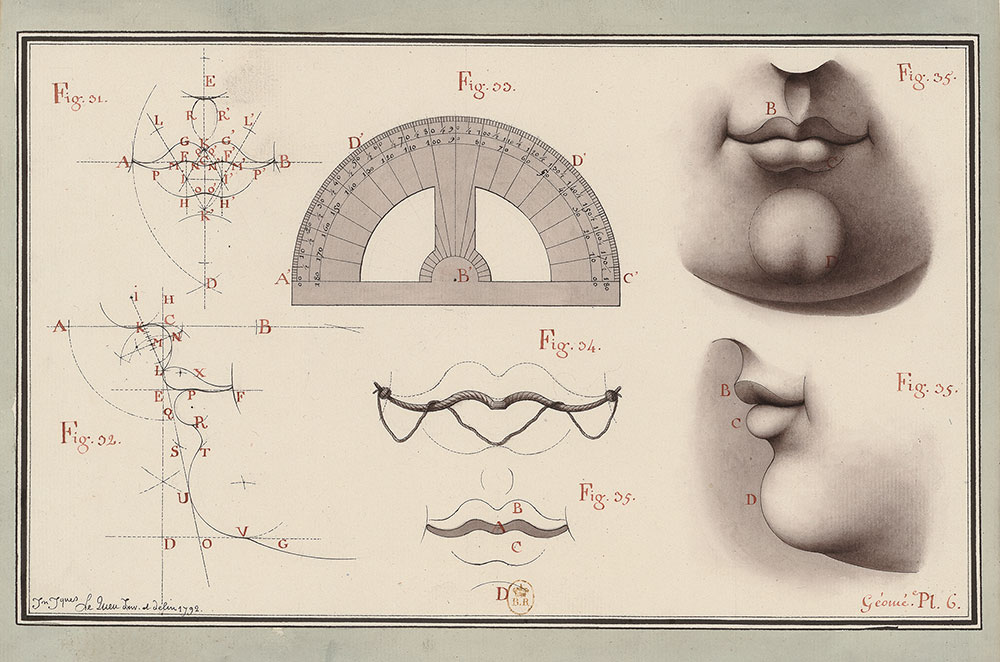

Study of Mouths, from New Method

Applying his methodical approach to proportions, Lequeu used a protractor to draw a mouth frontally and in profile. As diagrammed, the contour of lips drawn according to this method would be derived from a series of curved arches extrapolated from a sequence of fixed points. The commentary compares the sinuous line of a closed mouth to a cupid’s bow, evoking the “sweet melancholy smile” of Venus’s “perfect mouth.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Study of Mouths, from New Method, 1792

Pen and black ink, gray-brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Study of a Head, from New Method

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Study of a Head, Seen from Behind, from

New Method, 1792

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Study of a Head, Seen from Behind, from New Method

To understand the structure that underlies facial beauty and expressions, Lequeu studied the musculature of

the face and its geometric components. His notes on proportions indicate his familiarity with published anatomical texts. Lequeu’s commentary, however, ironically acknowledges the limitations of his method, noting that “it would be impossible to determine the true combination of passions on our face.”

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Study of a Head, from New Method, 1792

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Proposal for the Dome of Sainte-Madeleine, Rouen

In 1773, the Rouen architect Jean Baptiste Le Brument was entrusted with building a chapel for the city’s hospital and proposed capping the building with a stone dome. Lequeu, who worked for Le Brument, drew a design for the stone dome from five different angles on this sheet. At lower left, it is outlined horizontally in a rectangular diagram, half viewed from underneath and half from above. This is elaborated in the upper registers, showing an exterior elevation and two cross- sections, with and without coffering. The designs are connected by dotted lines and corresponding letters,

inviting viewers to rotate the imaginary structure in their mind’s eye. (Ultimately, a lighter and less costly wooden- framed structure was adopted.)

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Proposal for the Dome of Sainte-Madeleine, Rouen, 1775

Pen and black ink, gray and brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Perpendicular Section of the Verdiers Mill

The date of this design’s creation and the location

of the mill it depicts—the town of Guiseniers, between Rouen and Paris—suggest that Lequeu executed it during one of his frequent stays at his granduncle’s residence there. The detailed rendering and precisely numbered list of components elaborate on an illustration of rustic agriculture in Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie (1751–66), which Lequeu studied closely.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Perpendicular Section of the Verdiers Mill, 1778

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

A Stove for the Ceremonial Staircase at the hôtel de Montholon

Stoves, often used in place of fireplaces to heat structures, were frequently placed in thoroughfares where residents would not linger. Lequeu took this necessary but smoky feature as the basis for a meditation on architectural and bodily heat. A snaked column alludes to the famous serpentine tripod at Delphi, playfully comparing the hot air produced by the stove with oracular smoke. Above the firebox, the chaste goddess Diana holds an oil lamp suggestively, emphasizing the tension between the heat of desire and the virginity required to tend the temple fire.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

A Stove for the Ceremonial Staircase at the Hôtel de Montholon, 1785

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

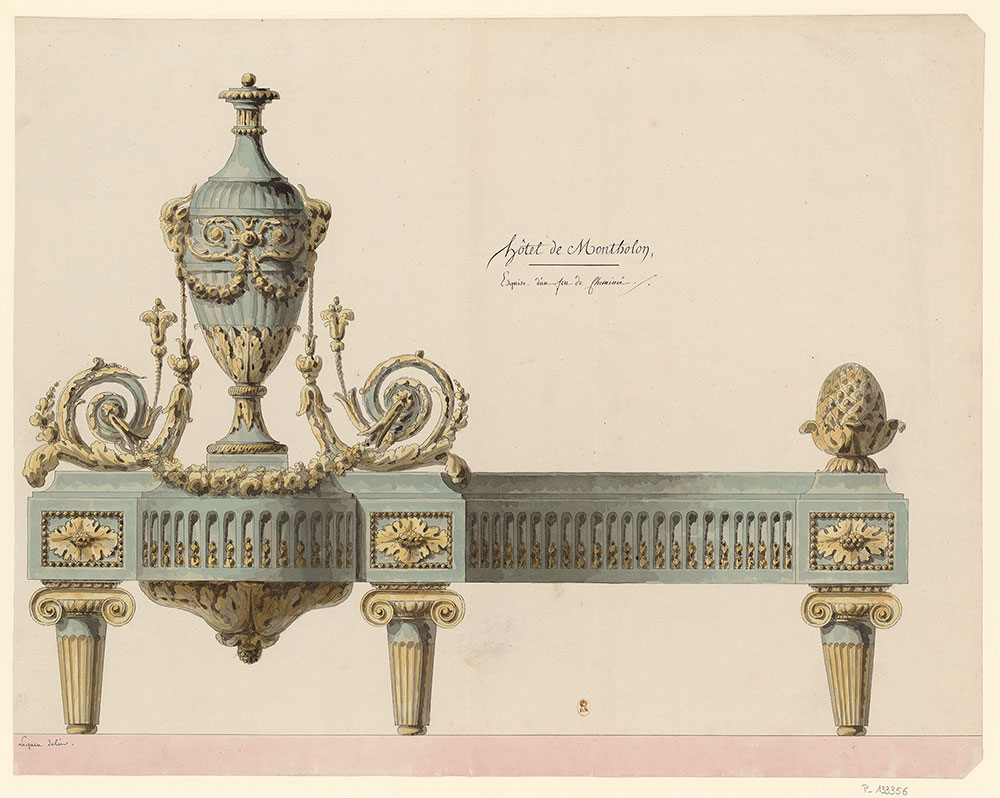

An Andiron for the hôtel de Montholon

The Hôtel de Montholon, built in 1785 by François Soufflot and still standing on one of the Grands Boulevards in northern Paris, is a rare example of a sumptuous neoclassical mansion of the eighteenth century. Lequeu was appointed site foreman, in charge of its construction and interior design. This unrealized design for a living room is dominated by a pair of caryatids, sculptural columns in the form of young women thought to have been enslaved symbolically as architectural supports.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for a Living Room at the Hôtel de Montholon, 1785

Pen and black ink, gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Design for a Living Room at the hôtel de Montholon

The Hôtel de Montholon, built in 1785 by François Soufflot and still standing on one of the Grands Boulevards in northern Paris, is a rare example of a sumptuous neoclassical mansion of the eighteenth century. Lequeu was appointed site foreman, in charge of its construction and interior design. This unrealized design for a living room is dominated by a pair of caryatids, sculptural columns in the form of young women thought to have been enslaved symbolically as architectural supports.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Design for a Living Room at the Hôtel de Montholon, 1785

Pen and black ink, gray wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Façade of a Pleasure Palace, called the Temple of Silence

In an effort to establish his architectural career, Lequeu courted aristocratic clients with designs for country residences in the waning moments of the ancien régime. Construction began on a villa in Rouen for one patron, Louis-Jacques Grossin, comte de Bouville, but the project was halted by the revolution and the count’s flight from France. That this intimate villa was conceived as a Temple of Silence is indicated by the figure of Harpocrates, the Hellenistic god of secrets, in the tympanum. The design was included in an 1813 publication on civil architecture by Lequeu’s friend Jean-Charles Krafft, suggesting contemporary awareness of the artist’s work.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Façade of a Pleasure Palace, Called the Temple of Silence, 1788

Pen and black ink, brown wash, watercolor

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie