Face-to-face with Lequeu

Lequeu’s donation to the Royal Library reveals his desire for recognition: it included notes for an autobiography, letters, newspaper articles, instructional essays and manuals, and a significant cache of self-portraits. He restricted the display of his 1792 self-portrait (shown nearby) until 1850. This focus on controlling the spread of his work indicates a concern for his legacy, which consisted largely of his drawings.

Spanning the range of his career, Lequeu’s self-portraits give a sense of the artist as an individual, one whose adaptability served him well during an era of political upheaval. Lequeu offered portrayals of himself as an intellectual, formally posed among his books, and as a citizen, informally attired and in profile. He also used himself as a model for a series of physiognomic studies exploring comic and dramatic expressions of emotion. These works underscore Lequeu’s complex persona and hint at the broad range of his interests, which extended far beyond inventive architectural designs.

Self-portrait (Jean-Jacques Lequeu Reflecting)

In the 1822 catalogue he prepared for the sale of his drawings, Lequeu described himself as “reflecting” in this self-portrait. Seated in a niche, he pauses in his studies. He is surrounded by his accomplishments, including the new map of Paris upon which he rests his arm. The inscription identifies him as an architect of the Rouen Academy, but the elements surrounding him deviate significantly from academic tradition and indicate his personal style as a designer. The pilasters contain fluted diamond-shaped panels that match his signet ring, while the keystone above him is adorned with a beaver, a natural builder.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Self-Portrait (Jean-Jacques Lequeu Reflecting), 1792

Pen and black and brown ink, brown and gray wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

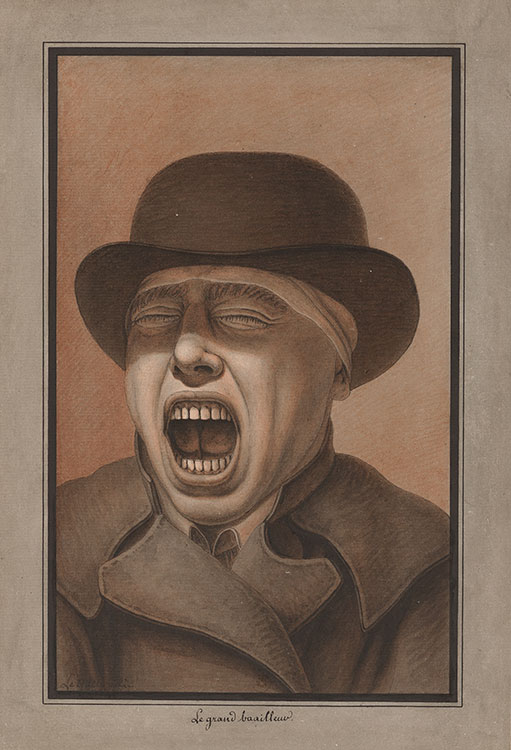

The Great Yawner

Lequeu inserted an additional a into the French word bailleur (yawner) identifying this man with his mouth agape, perhaps to echo the sound of a prolonged yawn. The artist was likely familiar with contemporary depictions of the subject, such as a 1783 self-portrait by Joseph Ducreux (1735–1802) in which he is shown midyawn and Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s 1781–83 bronze head of a yawning man.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

The Great Yawner

Pen and black ink, brown and gray wash, red chalk

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

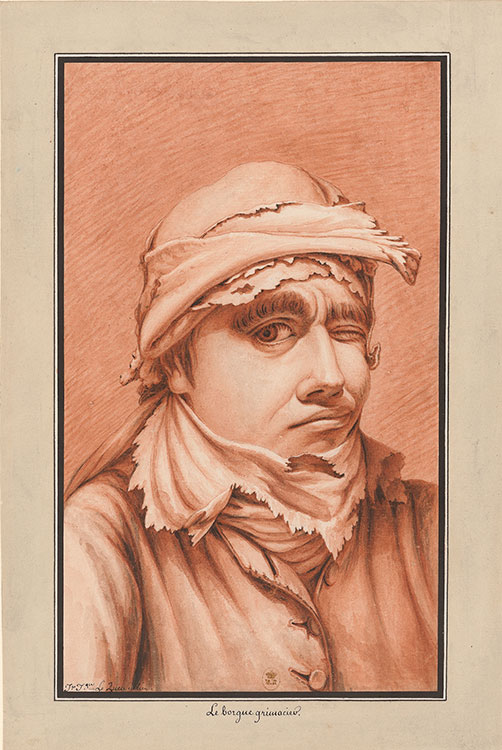

Squinting Man

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Squinting Man

Red chalk and wash, brown ink

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Pouting Man

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Pouting Man

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Jennifer Tonkovich: Welcome to Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect. Drawings from the Bibliothèque nationale de France. This is Jennifer Tonkovich, the Eugene and Clare Thaw Curator of Drawings and Prints here at The Morgan Library & Museum. Lequeu left us a paper legacy of more than 800 drawings, and among them are several sheets in which he used himself as the model. These self-portraits feed our curiosity about the individual behind this large and strange group of works. These drawings not only capture the artist's appearance, but also alert us to how he wanted to be seen. An informal profile portrait shows us a smiling Lequeu. In fact, he would've had to work with a friend in order to trace his profile. He heartily approved of this particular portrait, noting that it was a good likeness. In a more formal self-portrait, he poses as an architect from Rouen who wants to be seen and remembered as an educated professional, well-groomed, reflective, and surrounded by his work. Less straightforward is the striking series of physiognomic studies in which he depicts himself with exaggerated facial expressions. These works invite us to imagine him sitting in his modest apartment, looking at himself in a mirror, pulling faces and trying to capture them on the page. He preens, he pouts, he makes vulgar gestures, he's bare-chested or in tattered clothes. These solo performances raise compelling questions. Who was his imagined audience? Is Lequeu, who wrote several plays, acting for us? Are these meant to be amusing? What do we make about the poignant air of self-pity that arises from the mockery? We know Lequeu thought about the intimate nature of portraiture and how a likeness could also serve as an object of desire. In his writings, he wondered what would've happened "if I had been favored enough by nature, or rather happy enough, for a woman to desire the imitation of my features?"

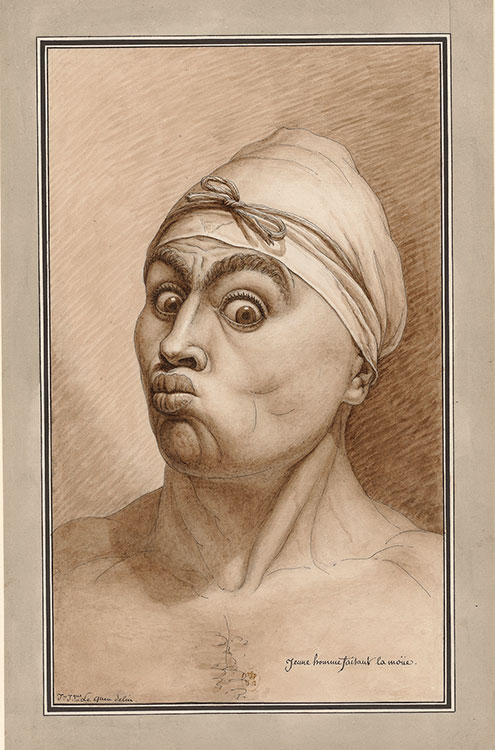

Preening Man

Lequeu’s careful studies of facial expressions also function as self-portraits, revealing the artist at different stages of life and in a range of moods. As with the character heads sculpted by Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (1736–1783) first exhibited in Vienna in 1793, Lequeu’s portraits examine how facial expressions convey not only fleeting emotions but also ingrained elements of a subject’s personality. Here, the bare- chested artist, his head wrapped in a flannel, puckers his lips and raises his brows in a parody of vanity.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Preening Man

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

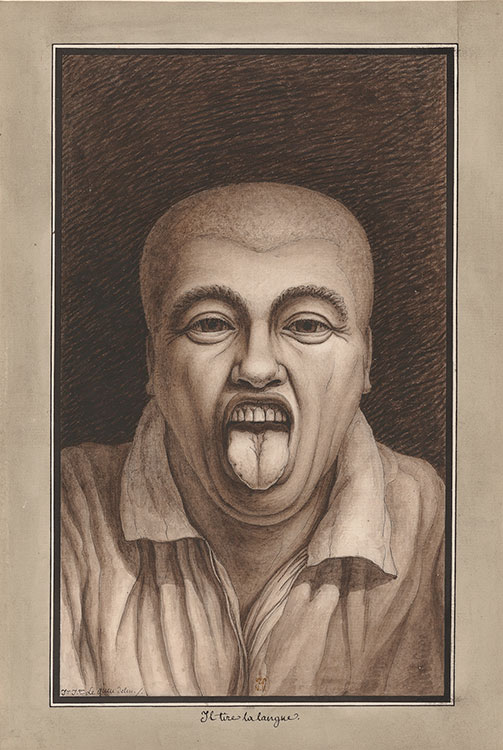

He Sticks Out His Tongue

Wearing an open-necked shirt and with his head shorn, a man opens his mouth wide to stick out his tongue, a bold and direct gesture that is striking in its vulgarity.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

He Sticks Out His Tongue

Pen and black ink, brown wash

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie

Self-portrait in Profile

Lequeu indicated in his inscription—“This second profile much more closely resembles Jean Jacques Lequeu Junior, Architect”—that he was pleased with this attempt at capturing his likeness, produced when he was thirty- six years old. In an open-necked shirt, his hair tied back with a cord, the artist appears at ease. The profile portrait, a popular style during the revolutionary era, harks back to ancient Roman coins, and Lequeu himself was a collector of coins and medals. To outline himself in profile, Lequeu likely relied on a physionotrace, a recently invented device for drawing silhouettes.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826)

Self-Portrait in Profile, 1793

Pen and black ink and wash, over black chalk

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie