Prophet of the Avant-Garde

You are free to see in Mister Ubu as many allusions as you like, or, if you prefer, just a plain puppet, a schoolboy’s caricature of one of his teachers who represented to him everything in the world that is grotesque.

—Alfred Jarry, address to the audience at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre, 1896

In a career spanning just thirteen years, Jarry produced an eclectic body of work that has reverberated in the art and literature of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Writers and artists have drawn upon Jarry’s work at moments of historical and cultural change, most acutely on the eve of the Second World War and at the advent of counterculture movements in Europe and America. A metaphor for political corruption and injustice, Ubu—like the spiral on his belly—is also a symbol of pataphysics and its infinite applications in the conception of alternative realities. The character also stands in for the author himself as an oracle of life’s absurdities and as an icon of the subversive imagination. Jarry’s adoption of Ubu as an alter ego, paralleled in his use of puppets, technology, and appropriated texts and imagery as “original” works of art, continues to resonate in the indirect gestures of the readymade and other idea-based art. Works in this section point to some of the evidence of Jarry’s continuing legacy in the modern era.

Messalina

Oscar Wilde and Arthur Symons drew attention to Jarry’s works in England during his lifetime; and the Scandinavian poet Sophus Claussen made an aborted attempt to translate Ubu roi into Danish. It was in Prague, however, where the first full translation of Jarry’s work appeared. His novel Messaline (1903) was serialized in 1904 in Arnošt Procházka’s seminal journal of the Czech avant-garde, Moderní revue, and was issued by the magazine’s imprint in book form in 1908. Jarry’s works would continue to hold sway in Central and Eastern European countries throughout the twentieth century as a touchstone for artists’ responses to totalitarian regimes.

For the subsequent generation of artists and writers, Jarry’s iconoclasm came to define the ethos of the modern avant-garde. His influence owes much to his encounter with the Italian Futurist poet, F.T. Marinetti (1876–1944), and close friendship with Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918), the poet who would coin the terms cubism and surrealism. Marinetti called Jarry “the unquestionable literary genius of the underworld.” It was Apollinaire’s accounts of Jarry after his death, however—the gun-waving antics and eccentric lifestyle and dress—that left an indelible mark on the latter’s legacy.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Messalina ([Prague]: Moderní bibliotéka, 1908). The Morgan Library & Museum, anonymous gift for the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection, 2017. PML 197675. Anonymous gift, 2017.

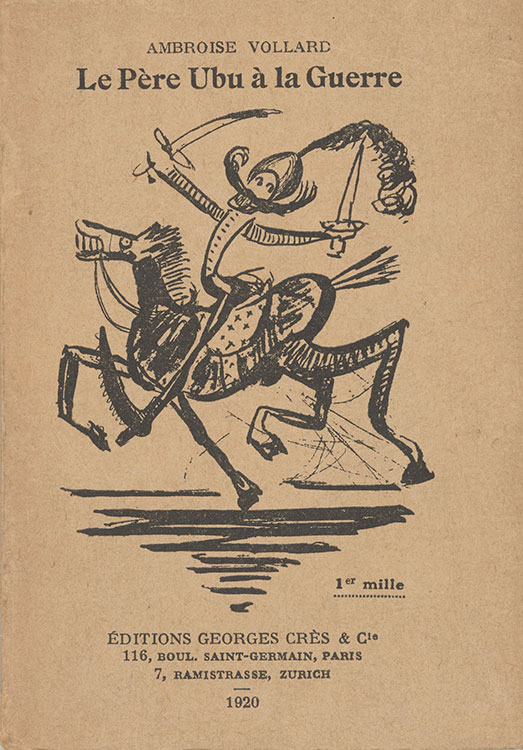

Ambroise Vollard

Ambroise Vollard—gallerist, publisher, and friend to Jarry—wrote comedic texts featuring Ubu during and after World War I. A symbol of collective tyranny and of the mindless mob, Vollard’s Ubu appears in colonial settings, hospitals, and battlefields. To illustrate his series of publications, Vollard called upon artist friends with radically different aesthetics: Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), Jean Puy (1876–1960), and Georges Rouault (1871–1958).

Ambroise Vollard (1867–1939), Le Père Ubu à l’aviation. Cover illustration by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), (Paris: Éditions Georges Crès et cie, 1918). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197109. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Le Père Ubu à la guerre

Ambroise Vollard (1867–1939), Le Père Ubu à la guerre, dessins de Jean Puy (Paris: Éditions Georges Crès et cie, 1920). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197113.

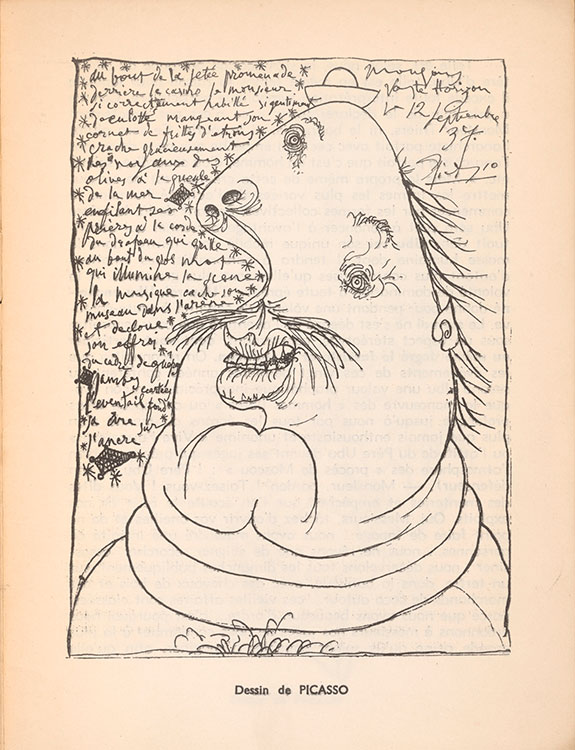

Pablo Picasso

Legends surfaced, proliferated by Apollinaire and Max Jacob (1876–1944), among others, about encounters between Pablo Picasso and Jarry. Some were undoubtedly apocryphal; they were made further credible, however, by the number of sketches of Ubu and Jarry that Picasso left behind. The painter used Ubu as a symbol for injustice and oppression during the political upheavals of the 1930s, especially those wrought by the Spanish general, Francisco Franco. As Picasso became more proficient in French, he learned passages of Jarry’s plays by heart and collected his manuscripts and other artifacts, even claiming that his pet owls were ancestors of Jarry’s birds.

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), illustration, in Ubu enchaîné (Paris: s.n., 1937). The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2018. PML 198110. © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

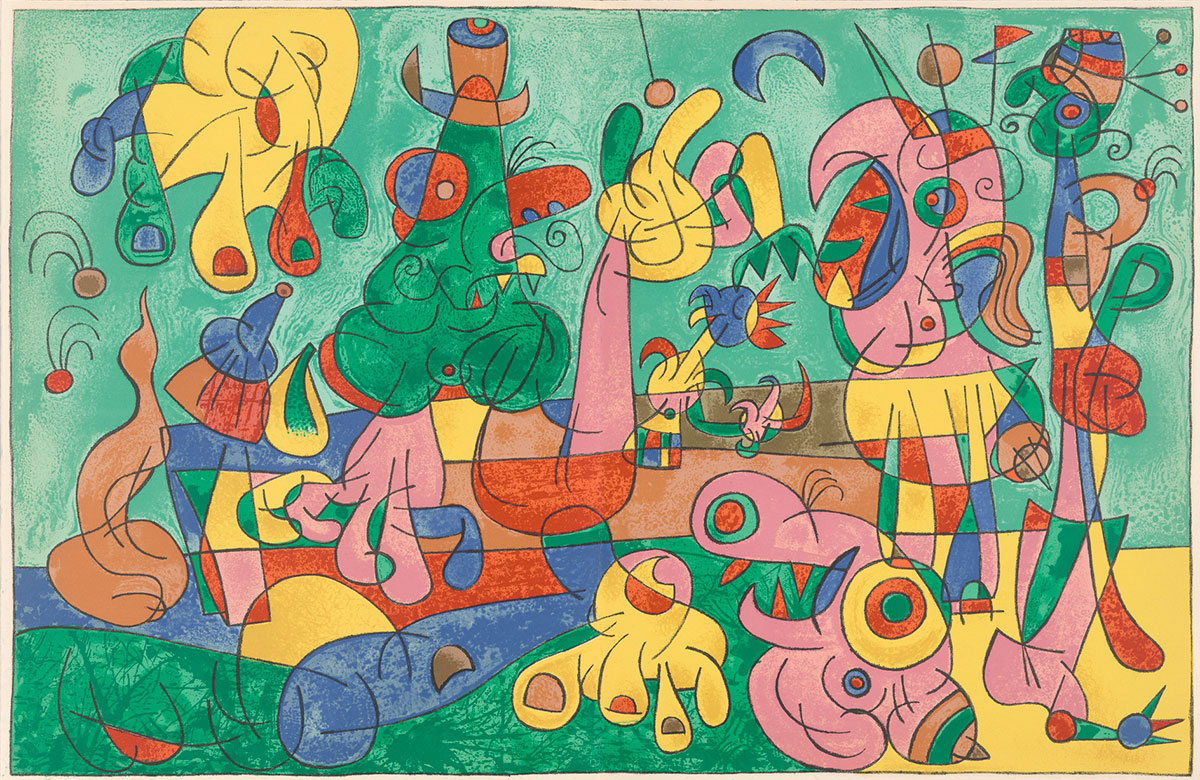

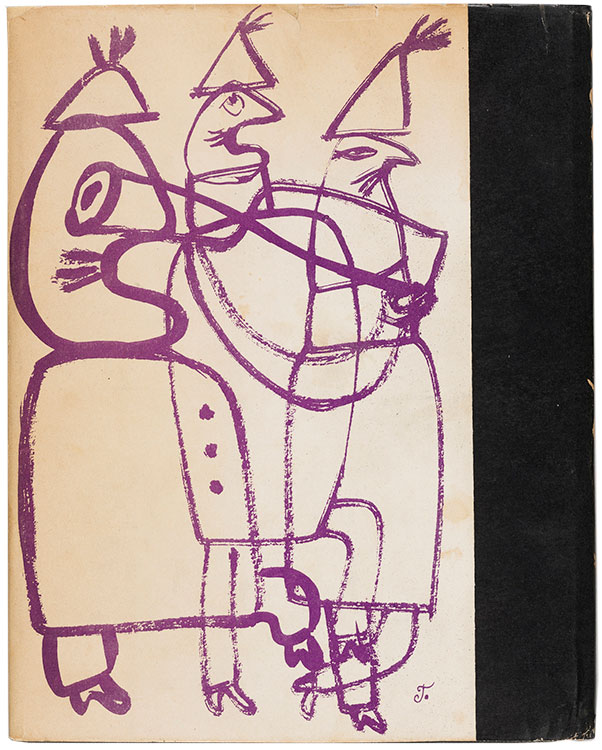

Joan Miró

On the fortieth anniversary of Jarry’s death, Joan Miró (1893–1983) signed a contract to illustrate Ubu roi. The ambitious edition took two decades to complete. The Catalan painter had been drawn to Jarry’s work since the 1920s, not only his most celebrated play but also his drawings, theoretical writings, and the novels Docteur Faustroll and Le surmâle. For Miró, as for Picasso, Ubu symbolized the corruption of the Franco regime in Spain. As he grew older, he expanded his interpretation of the character in projects both sinister and playful, creating his own adventures that imagined Ubu’s childhood. Eventually, Miró’s conception of Ubu came to encompass all that was base in humanity—including, the painter once said, the art market.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi, lithographies originales de Joan Miró (Paris: Tériade éditeur, 1966). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197100. © Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris 2019.

Dora Maar

Maar is known for her beautiful and surreal black-and-white photomontages, which often combine street photography with erotic fragments of the female body. This image of an armadillo fetus is exceptional in her oeuvre for its repellent qualities. Maar’s original title for the work was Portrait d’Ubu. At the first exhibition of Surrealist objects in Paris in 1936, the curators grouped the photograph with “interpretations of found objects.” Throughout her life, Maar neglected to explain the subject or title of the work. Its creation coincided with her participation in Parisian radical anti-fascist movements spearheaded by the writers Georges Bataille and André Breton.

Dora Maar (1907–1997) Père Ubu, 1936, gelatin silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gilman Collection, Purchase, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, by Exchange, 2005; 2005.100.443. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

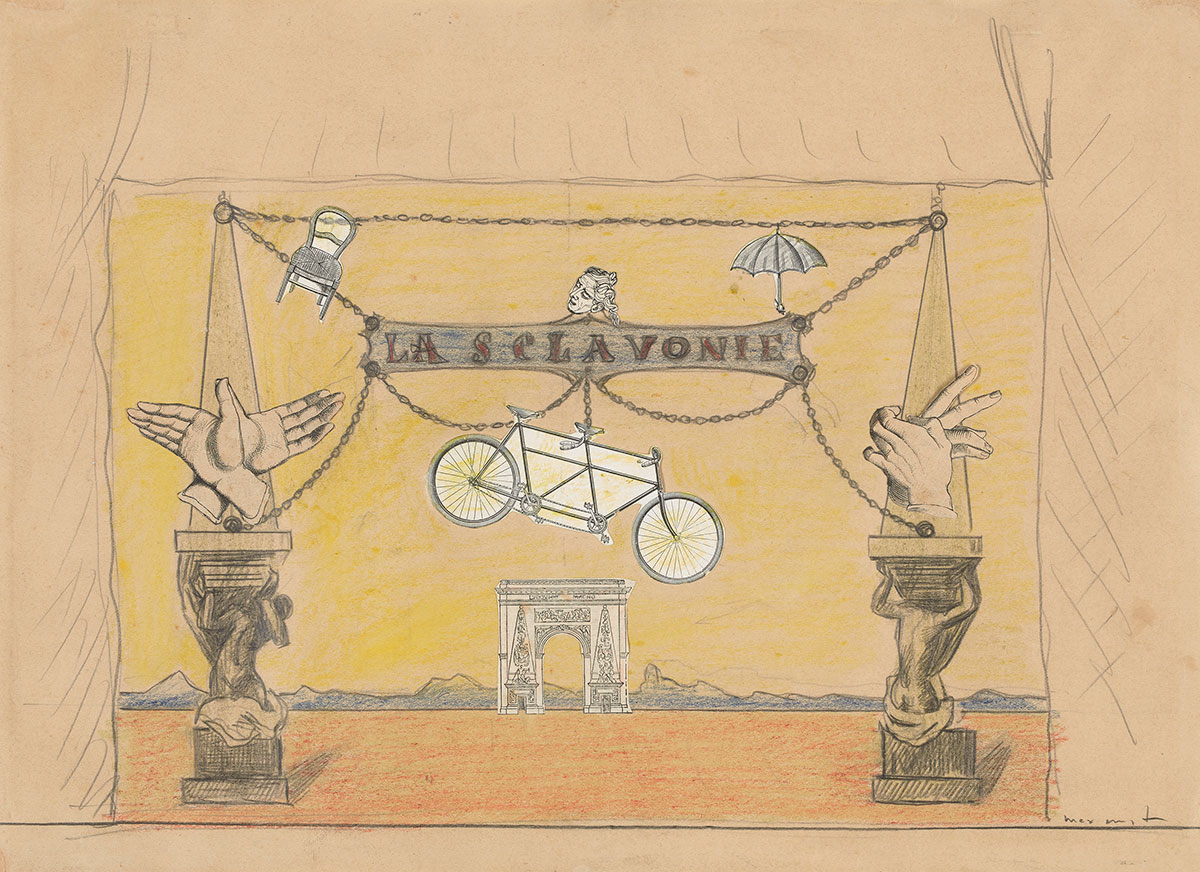

Max Ernst

The rise of nationalism was the subtext for Sylvain Itkine’s 1937 world premiere of Jarry’s 1899 play Ubu enchaîné. André Breton oversaw the design of the program, which contained texts and illustrations by Paul Eluard, Pablo Picasso, René Magritte, and other figures associated with Surrealism. Max Ernst’s set designs for the production were based on his collages of found imagery and drawings. Breton called Jarry “the master of us all.” For the Surrealists, Ubu was not only a tyrant: in their collaborative deck of tarot cards Le jeu de Marseilles, the group used Jarry’s woodcut portrait of Ubu as the joker.

Max Ernst (1891–1976), set design for Alfred Jarry, Ubu enchaîné, 1937, graphite and wax crayon, with collage of cut relief-printed papers, on tan wove paper. The Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph R. Shapiro, 1992.220. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

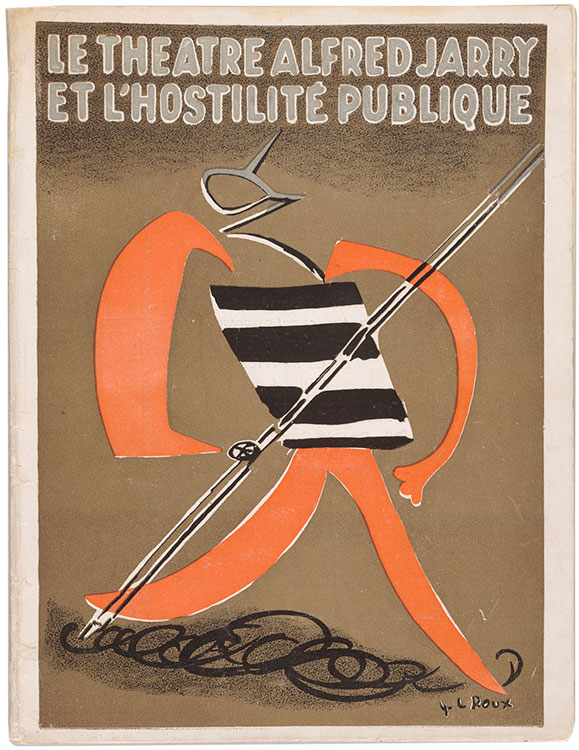

Le Théâtre Alfred Jarry et l’hostilité publique

After breaking with the Surrealists, Antonin Artaud and Roger Vitrac formed Le Théâtre Alfred Jarry, taking inspiration from Jarry’s antinaturalist theatrical philosophy and the burlesque brutality of performance inherent in Ubu roi. This booklet, which served as a manifesto as well as a complete history of the company, appeared just after hostile reactions in the press and among their peers had caused the group to disband. The section documenting critics’ blurbs used quotations from both real and fictional reviews (a few opinions were attributed to Père Ubu).

Antonin Artaud (1896–1948) and Roger Vitrac (1899–1952), Le Théâtre Alfred Jarry et l’hostilité publique, cover illustration by G.-L. Roux (1904–1988) [Paris: s.n., 1930]. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2017. PML 197100.

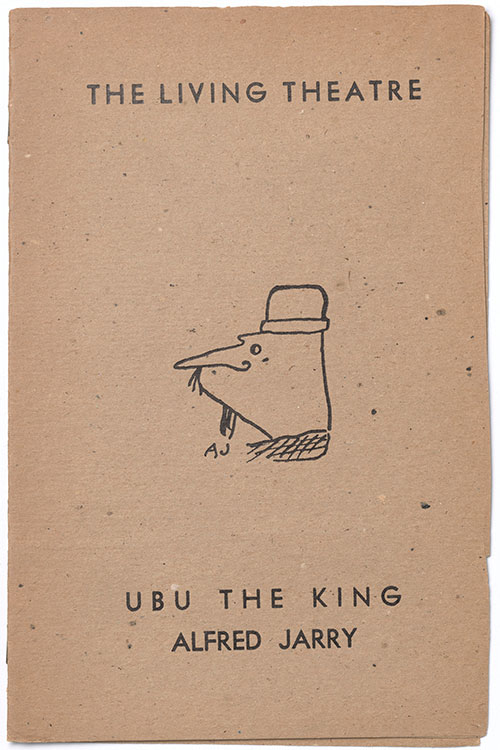

Ubu the King

After the Second World War, Jarry’s identification as a provocateur and an icon of free expression made him a touchstone for burgeoning countercultural movements. Underground magazines such as Free Unions, Evergreen Review, and Gnaoua featured translations of his work as a bridge spanning late Surrealism, the Theatre of the Absurd, and experimental literature of the 1950s and 1960s. The Living Theatre, founded in New York by Judith Malina and Julien Beck, used one of Jarry’s drawings of Ubu on a program when staging his drama in tandem with a play by the avant-garde poet, John Ashbery.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu the King [and] John Ashbery (1927–2017), The Heroes (New York: [The Living Theatre], [1952]). The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2018. PML 197920.

Mary Reynolds and Marcel Duchamp

“Rabelais and Jarry are my gods,” Marcel Duchamp once stated. Jarry’s engagements with machines, science, alter egos, wordplay, and the letter r certainly resonate in Duchamp’s works. His friend Mary Reynolds (1891–1950) was one of the few Surrealist devotees of Jarry to express herself through the art of bookbinding. She created unique bindings for all of Jarry’s major works. Her first project, shown at left in the case, realized Duchamp’s design for an edition of Ubu roi. The U-shaped covers synthesize the work in one letterform—a gesture Jarry himself made in reference to the second letter r in the play’s first word, “merdre.” It also suggests a pun in English (you are Ubu).

Reynolds’s extraordinary binding design for Docteur Faustroll, shown at right, suggests an assimilation of Jarry and Duchamp. The perforated copper sheets on the covers, which allude to Faustroll’s sieve-bottomed boat, are framed like the windowpanes in versions of Duchamp’s miniature readymades. Inside the book’s covers, Reynolds chose the color green for the silk endpapers, reflecting both Ubu’s signature expletive (“By my green candle!”) and the green silk lining of Duchamp’s The Green Box (1934).

At left in case: Mary Reynolds (1891–1950) and Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), bookbinding, ca. 1934–35, goatskin, gilt, silk, and glassine, on Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Librarie Charpentier et Fasquelle, 1921). The Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries. At right in case: Mary Reynolds (1891–1950), bookbinding, ca. 1940, calf and other leathers, copper, gilt, and glassine, on Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Gestes et opinions du Docteur Faustroll, pataphysicien (Paris: Librairie Stock, 1923). The Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries.

Franciszka Themerson

Two women shaped the reception of Jarry’s writings in the English-speaking world. For a 1951 edition of Ubu roi, artist and small-press publisher Franciszka Themerson (1907–1988) illustrated virtually every page and rendered Barbara Wright’s translation in calligraphic handwriting. Their version of the play became the most widely disseminated text by Jarry in English. Themerson’s engagement with Jarry persisted for several decades. She went on to design sets, masks, and costumes for the landmark production of the play in 1964 at the Marionetteatern in Stockholm.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi: A Drama in 5 Acts, translated by Barbara Wright (1915–2009), illustrations by Franciszka Themerson (1907–1988) (London: Gaberbocchus Press, 1951). The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2019. PML 198260. © Themerson Estate.

Readies for Bob Brown’s Machine

After there was no one left in the world, the painting machine, animated inside by a system of weightless springs, revolved . . . like a spinning top, . . . dashed itself against pillars, swayed and veered in infinitely varied directions, and followed its own whim in ejaculating onto the walls’ canvas the succession of primary colors . . . this modern deluge.

—Alfred Jarry, Docteur Faustroll

The autonomous creativity of Faustroll’s painting machine reverberates in some of the machine-based art since the Second World War. It has also been a factor in experimental literature. The expatriate writer Bob Brown (1886–1959) proposed that humans should learn to see words “machine-wise.” He invented a reading machine to transform words into optic images. A single line of microscopic text would pass under a lens and then be projected directly into a person’s mind by means of light—ideally, according to Brown, at great velocity. To suit the project, Brown devised a new genre of writing he called readies—a neologism combining the words read, ready, and talkies. Soliciting contributions from Gertrude Stein and William Carlos Williams, among others, Brown added arrows and dashes to encourage the mutual acceleration of machine and human perception.

Bob Brown (1886–1959), Readies for Bob Brown’s Machine (Cagnes-sur-Mer: Roving Eye Press, 1931). The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2018. PML 197919.

Collège De ’Pataphysique

One of the central tenets of the Collège de ’Pataphysique, manifest in all its endeavors, is Jarry’s idea that the comedic is profoundly serious. Founded in 1948 by devotees of Jarry’s imaginary science, the college is headed by the Inamovable Curator, Doctor Faustroll; for several years, a crocodile served as Vice-Curator. Members—some with honorifics such as Transcendent Satrap and Commander of the Order of the Grand Gidouille—have included Marcel Duchamp, Jean Dubuffet, Max Ernst, Eugène Ionesco, Tanya Peixoto, and the Marx Brothers. A constant over more than seven decades has been the attention paid by pataphysicians around the world to the aesthetics of book and magazine design. The works displayed here on the wall and in the case echo Jarry’s serious yet playful experiments in the art of the book.

Installation view: Alfred Jarry: The Carnival of Being, Engelhard Gallery, January 24 through 10 May 2020. Publications of the Collège De ’Pataphysique, Paris. Top (left to right): Soleil de printemps, illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), [1957]. Hymne des palotins: Tel qu’il fut chanté more antiquissimo à la première d’Ubu cocu le 4 merdre lxxiii, [1952]. Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), Oukiva trene sabot, [1958]. Bottom (left to right): Claude Terrasse (1867–1923), Seconde version musicale de la Chanson du décervelage, [1956]. Raymond Queneau (1903–1976), Lorsque l’esprit, [1954]. Irénée-Louis Sandomir [i.e., Emmanuel Peillet] (1914–1973), Oraison funèbre de Mélanie le Plumet, [1949]. Jean Mollet (1877–1964), Jarry inconnu, [1962]. Les nouveaux timbres, [1952]. Tatane, [1954]. Case (left to right): Viridis Candela: Cahiers du Collège de ’Pataphysique, no. 1 (April 1950). Le vieux de la montagne (Geneva: Éditions Connaître, [1957]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. Boris Vian (1920–1959) and Stanley Chapman (1925–2009), ’Pataphysics? What’s That? (London: The London Institute of ’Pataphysics, 2006). The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2019. PML 198472. Roger Shattuck (1923–2005) and Simon Watson Taylor (1923–2005), eds. “What is ’Pataphysics? [’Pataphysics Is the Only Science].” Cover after a design by Juan Esteban Fassio (1924–1980). Special issue, Evergreen Review 4, no. 13 (1960). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017.

Evergreen Review

Like the sorcerer’s apprentice, we have become victims of our own knowledge—principally of our scientific and technological knowledge. In ’Pataphysics resides our only defense against ourselves. . . . Outwardly one may conform meticulously to the . . . conventions of civilized life, but inwardly one watches this conformity with the care and enjoyment of a painter choosing his colors. . . . ’Pataphysics, then, is an inner attitude, a discipline, a science, and an art, which allows each man to live his life as an exception, proving no law but his own.

—Simon Watson Taylor, “Superliminal Note,” 1960

In 1960, English-speaking members of the Collège de ’Pataphysique presented pataphysics to a broad audience for the first time in Evergreen Review. The editors pointed to the subject’s timeliness: the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, publicized the previous year, had posited that every outcome of an event is realized in divergent parallel universes. Readers have continued to sift through Jarry’s enigmatic writings in order to define pataphysics; in recent decades, however, figures in the arts and sciences have devoted more energy to creating works based on their individual interpretations. Several central ideas persist: universal equivalence, supplementary realities, and a science that is governed by particularities and exceptions—to which some have added the axiom that to understand pataphysics is to fail to understand pataphysics. The London Institute of Pataphysics continues to elaborate upon Jarry and his constellation as a pataphysical artist and thinker of the past, present, and future.

Roger Shattuck (1923–2005) and Simon Watson Taylor (1923–2005), eds. “What is ’Pataphysics? [’Pataphysics Is the Only Science].” Cover after a design by Juan Esteban Fassio (1924–1980). Special issue, Evergreen Review 4, no. 13 (1960). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197062. © 1960 by Evergreen Review. Used by permission of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

Thomas Chimes

Chimes’s lifelong interest in Jarry and, in particular, ideas associated with his novel Docteur Faustroll informed a series of panel portraits followed by white paintings and what he called the Hermes Cycle. Figures in the white paintings materialize and dissipate in a void of translucence—suggestive of the author’s own neologism, ethernity, where time converges with light and the dimensions of the universe. Both the white paintings and the panel portraits were based on the few surviving photographs of Jarry. The convergence of contemporary painting and photographic documentation of the present (now perceived from the future as the past) enabled Chimes’s exploration of Jarry’s pataphysical notions of Time.

Thomas Chimes (1921–2009), Alfred Jarry (Departure from the Present), 1973, oil on panel. The Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection. Courtesy of Locks Gallery.

William Kentridge

Kentridge once stated that Ubu resides in all of us. In this series of eight etchings, the artist suggests a kind of hybrid self-portraiture. Kentridge used photographs of himself as the basis for the figures and juxtaposed them with the grotesque body of Ubu, rendered cartoonishly in chalk. The works originated in the context of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee hearings in the postapartheid era of the artist’s native South Africa. Revelations of the government’s barbarity, as well as the victims’ unresolved desire for both retribution and amnesty, informed Kentridge’s exploration of art attuned to ambiguity. Kentridge continued to use Ubu in works across mediums, including, and often combining, drawing, painting, animation, theater, video, and sculpture.

William Kentridge (b. 1955), Ubu Tells the Truth, 1996–97, hardground, softground, aquatint, drypoint, and engravings. The Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection. The Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.