Beautiful Like Literature

In the fiction and journalism Jarry published in the twentieth century, his engagement with printed matter expanded from innovations in book designs to ideations of the medium in writing. Documents, imaginary libraries, and the literature of visionary science play central roles in his tour de force, Docteur Faustroll. Subtitled “a neo-scientific novel,” the work elaborated on pataphysics for the first time and, in its sheer experimentation, forecast landmarks of literary modernism.

Faustroll and his 1902 novel, Le surmâle, also manifested Jarry’s conceptions of technology in artistic practice. His cultivation of hybrid personae throughout his life, unifying puppet and puppeteer in theater and Alfred and Ubu in real life, persisted in his exploration of the creative assimilation of man and machine. On one occasion when he casually fired a gun at another man, Jarry described the act as “beautiful like literature.” This lack of separation between artistic gestures and their presumed opposition in extreme pastimes and play suggests an equivalence between performance and life, between art and non-art—what André Breton would later characterize as a paradigmatic shift. After Jarry, the differentiation between art and life was annihilated.

© RMN-Grand Palais / Erich Lessing/ Art Resource, N.Y.

La machine à explorer le temps

Jarry showcased his rhetorical virtuosity and irreverence later in life by publishing a book’s worth of speculative essays in magazines. Among many of the subjects Jarry addressed were cannibalism, a machine to beat women, and “killer pedestrians”; his review of a new postage stamp described it as a depiction of a blind prostitute (it was in fact the female personification of the French Republic). In one of his most famous vignettes, “The Passion Considered as an Uphill Bicycle Race,” Jesus gets a flat tire after riding over a bed of thorns and has to carry his wooden cross-frame bike up a hill over his shoulder.

Soon after H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine was translated into French, an article on how to build a time machine appeared under the byline of Jarry’s fictional character, Doctor Faustroll. Jarry borrowed passages from writings by the physicist Lord Kelvin to conceive of a real machine that was a gyroscopic device, initially described as analogous to a bicycle. Most of the essay was devoted to the phenomenon of time itself. Jarry proposed an “imaginary present” and defined time travel in pataphysical terms: isolated in a machine within the luminiferous ether, past and present could be explored simultaneously. Jarry emphasized his definition of duration typographically: “Duration is the transformation of a succession into a reversion. In other words: THE BECOMING OF A MEMORY.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), “Commentaire pour servir à la construction pratique de la machine à explorer le temps,” in Mercure de France, no. 110 (February 1899). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197152.

Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll

Faustroll, Jarry’s most imaginative and absurd novel, is a textual collage comprising the art, science, and people who shaped his aesthetic life. Treatises on pataphysics, legal documents, equations measuring the surface of God, and letters from another dimension are folded into a travel narrative about Faustroll, a bailiff, and a monkey whose sole utterance is “Ha Ha.” They set sail from Paris to Paris by sea on Faustroll’s copper mesh bed. Other beings on their voyage are three-dimensional elements conjured from an inventory of books Jarry calls the livres pairs (coequal or equivalent books). Twenty-fourth on that list is an anonymous play titled Ubu roi. Across “foliated space,” Faustroll draws from it “the 5th letter of the first word in the first act”—in other words, the second r in Jarry’s linguistic distortion merdre—synthesizing in one letterform (one piece of type) his radical transformation of artistic practice.

Henri Rousseau also makes an appearance in the novel: he defaces banal art with a painting machine, which eventually projects its own works on the walls of a “Palace of Machines.” Rejected by publishers, Jarry added a note to the Faustroll manuscript predicting that it would not appear in print “until the author has acquired enough experience to savor all its beauties.” The book was published four years after his death at age thirty-four.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll, pataphysicien: Roman néo-scientifique, suivi de Spéculations (Paris: Eugène Fasquelle, 1911). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197152.

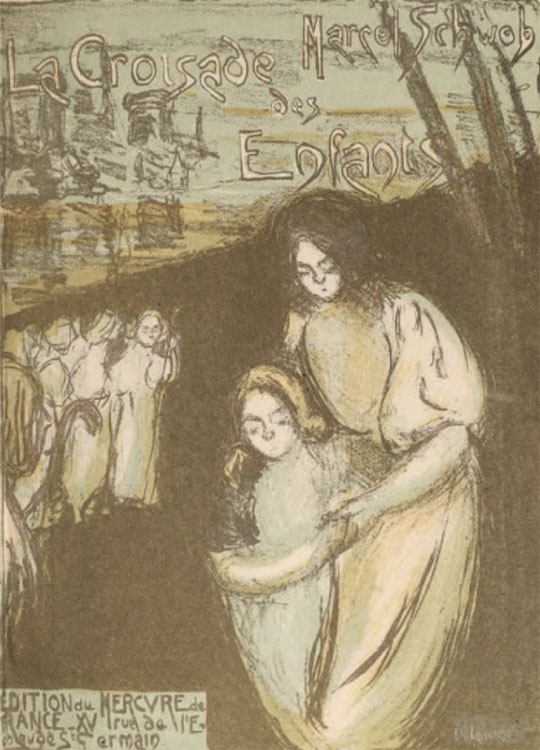

La croisade des enfants

Faustroll’s many departures from the conventions of nineteenth-century novels include Jarry’s persistent invocation of living writers and artists. Among the works Jarry draws attention to are Emile Verhaeren’s Les campagnes hallucinées, Bonnard’s poster for La revue blanche, and La croisade des enfants by the author who championed his early career, Marcel Schwob. Real scientists of the day—those prone to bizarre theories, at least— are also invoked and interwoven with explanations of pataphysics, Jarry’s “science of imaginary solutions.” In addition to the specter of Lord Kelvin, the physicist C. V. Boys looms large. Jarry used ideas from Boys’s 1890 book on soap bubbles to explain why Faustroll’s copper mesh bed was seaworthy.

Marcel Schwob (1867–1905), La croisade des enfants. Cover illustration by Maurice Delcourt (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2019. PML 198234.

Société des vélocipèdes Clément

At a time when bicycling was transitioning from a pastime to an athletic activity, Jarry used his Clément Luxe for commutes to and from the country and for intracity transportation. He exalted bicycles as a “new organ” for man and an extension of the skeleton. Kinetic man-machines, when ridden at top speed, had the potential, Jarry suggested, to transform the artist’s consciousness. Guns, fencing foils, and even fishing rods seemed to function the same way in Jarry’s pursuit of extreme recreation. All were inextricable from his artistic identity in his final years, blurring the lines between creative expression and life.

“Catalogue illustré des célèbres cycles Clément,” Société des vélocipèdes Clément, no. 4 (1895). Collection of Pryor Dodge.

Alfred Jarry fencing

Unidentified photographer, Alfred Jarry (at right) fencing with his teacher Félix Blaviel in Laval, 1906. The Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection.

Le surmâle

Encounters between man and technology in Le surmâle take on perverse and morbid characteristics. In the novel, a “love-inspiring-machine” electrocutes the hero after he demonstrates his supermale status by engaging in sex eighty-two consecutive times. The novel also features a ten-thousand-mile race between a locomotive and a five-man tandem bike. The riders are fueled with “perpetual motion food”—a compound chiefly comprised of strychnine and alcohol. Midway through the race, one of the cyclists dies; the corpse, whose feet are strapped to the pedals, continues on, however, and the “human mechanisms” outlast the train.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Le surmâle: Roman moderne. Cover illustration by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: Fasquelle éditeurs, 1970). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197614. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Vins en gros

Used in the extreme, “recreational” drugs—absinthe, wine, and ether—were devices Jarry used to supplement his imagination like a form of artificial intelligence. They also sapped his health and finances. After the magazines he depended upon for income folded, Jarry’s reputation as a delinquent in pecuniary matters became more pronounced. This envelope, addressed to Jarry by his wine merchant, contained one of the many outraged, threatening demands for payment overshadowing his final year. Jarry may have been intoxicated when he scrawled an indignant untruth on the back of the same envelope: “I always pay my debts.”

Envelope addressed by Gaston Jobard to Alfred Jarry, stamped 3 October 1907. On verso: Letter from Jarry to Jobard, October 1907. Collection of Christophe Champion, Librairie Faustroll.

“The Testament of Père Ubu”

In 1906, Jarry believed he was on the verge of death and wrote a letter to Rachilde that is now referred to as “The Testament of Père Ubu.” Jarry asks her to undertake a “posthumous collaboration” by finishing his novel after he dies. Writing about himself as Ubu in the third person, he concedes the irony that the author of The Supermale is now spent. Ubu’s furnace “is not going to explode, but rather just switch itself off . . . quite calmly, like an exhausted motor.” Jarry compares Ubu’s brain to a “perpetual machine” that will persist and dream without him. “He left such beautiful things on earth,” adds Jarry,“but he is disappearing in such an apotheosis! . . . He has armed himself before Eternity and is not afraid.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), letter to Rachilde, 28 May 1906 (“The Testament of Père Ubu”). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. MA 9074.