The Author of Ubu Roi

Jarry’s reputation as a genius provocateur solidified at the premiere of his play Ubu roi. The violent satire stemmed from puppet shows that were collaborations between Jarry, his sister, and two classmates in high school. Ubu, a grotesque buffoon inspired by their physics teacher, remained the vehicle for Jarry’s creative projects for the rest of his life.

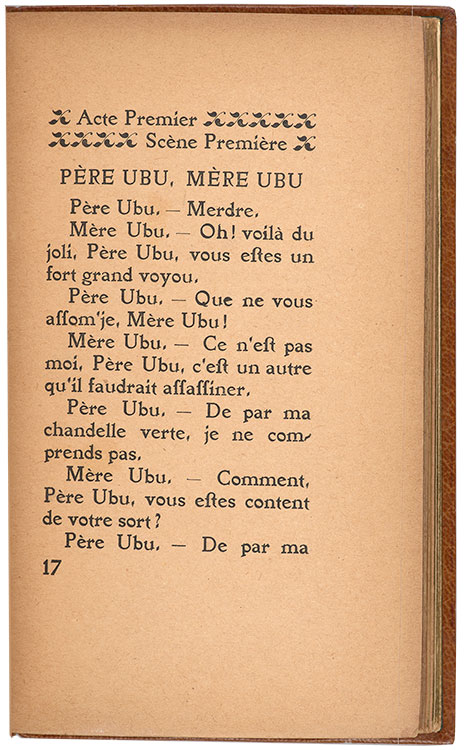

The plot was simple: A tyrant usurps the Polish throne. He slaughters his enemies, meets defeat at the hands of the Russians, and escapes on a vessel headed toward France. The first word uttered on stage was Ubu’s yawp: “Merdre.” Jarry’s neologism added a second r to merde, the French word for “shit.” Wearing a cardboard mask, Ubu appeared barely human and spoke in an unmodulated voice. His feral physicality unsettled the crowd, as did the scenery (every setting was combined on one painted backdrop). As a whole, Ubu roi seemed to signify the imposition of artistic will on established modes of making art, heightened by its absurdities and the author’s apparent indifference to the audience’s comprehension. The play’s public dress rehearsal and single performance reverberated for years to come.

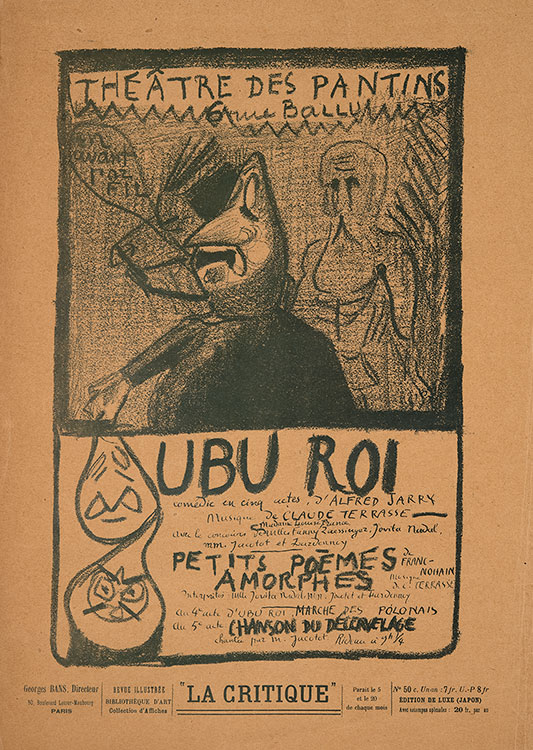

Program for Ubu roi

Jarry was in the midst of work on Perhinderion in early 1896 when he proposed a production

of Ubu roi to Aurélien Lugné-Poe, the director of the cutting-edge Théâtre de l’Œuvre. As incentive, Jarry volunteered to handle the Œuvre’s publicity and race around Paris on his bicycle to drum up subscriptions. He also helped to adapt the translation of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. Diminutive in size, Jarry played the part of a troll.

Lugné-Poe had first taken an interest in Jarry based on his experimental books and magazines. A postcard and an inscribed special copy of Les minutes in the Morgan’s collection suggest that, even as plans for Ubu roi were underway, the author continued to use his publications to gain the director’s confidence. Jarry’s determination to bring an equal degree of innovation to the stage, however, began to test Lugné-Poe. He was wary of Jarry’s reputation as an eccentric and was baffled by the play. He was on the verge of canceling the project until Rachilde assured him that, no matter what, Ubu roi would be a sensation. On 9 and 10 December, 1896, Rachilde’s prediction came true. It was a succès de scandale.

Program for Ubu roi at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre (Paris: La Critique), 1896. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray fund, 2019. PML 198466.

Ubu roi

Profanity was a common occurrence on cabaret stages in the 1890s. Jehan Rictus and Aristide Bruant were well-known for using what was then euphemistically called the “mot de Cambronne.” That a serious actor uttered a word that sounded like “shit” on the stage of a formal theater was something else altogether. The crowd booed and whistled for around fifteen minutes when Firmin Gémier delivered his first line; another lengthy interruption occurred later in the play when an actor’s hand served as a doorknob. The shouting doubled in volume after Gémier said Jarry’s name at the curtain.

Jarry had published an essay on the theater a few weeks before the premiere to prepare critics for Ubu roi. His radical ideas were summed up in the title: “The Futility of the Theatrical in the Theater.” For Jarry, actors and naturalist sets were the most “hideous and incomprehensible objects” cluttering the stage. He advocated for minimal props, to be moved around by handlers in plain sight. The use of cardboard masks and unnatural voices could transform performers into symbols, almost like letterforms, to express the writer’s ideas. By dispensing with the illusion of reality, a figure on stage could be a “walking abstraction” in service to the creator’s vision.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197019.

Program for Ubu roi

Jarry was the only playwright at the Œuvre to illustrate his own program (though uncredited, he also served as Ubu roi’s director and conceived its costumes and sets). His unusual design placed the actors’ names sideways, emphasizing the list of characters’ names instead. This is one of Jarry’s few depictions of Ubu without a spiral on his belly or a toilet-brush scepter in his hand. His distorted, mechanical arm holds a bag of money; the other bears a flaming candle or torch similar to the one held by the central figure in Rousseau’s painting La guerre.

Jarry’s addition of a leaf atop Ubu’s head would have been recognizable as an allusion to caricatures of Louis-Philippe I as a pear. The audience may have struggled to make sense of the burning house and the spheric creature, however. The kneeling men at the bottom left were copied from a late medieval woodcut Jarry had appropriated previously for his book César-antechrist.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), program for Ubu roi, 1896, lithograph. Collection Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University. Museum Purchase. Photography by Peter Jacobs

Ubu roi

Jarry’s revolt against norms onstage was equally apparent in his design for Ubu roi’s publication. The book was typeset in his Renaissance-style font, Perhinderion. The play’s lengthy subtitle, which referred to its origins as a high-school marionette play, was another echo of Renaissance printing practices. Jarry’s presentation of the seminal text of modern theater—with its radical mise-en-scène and shocking neologisms—was arcane, resembling early editions of canonic prose more than cutting-edge drama. It appeared six months before the play’s premiere.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197019.

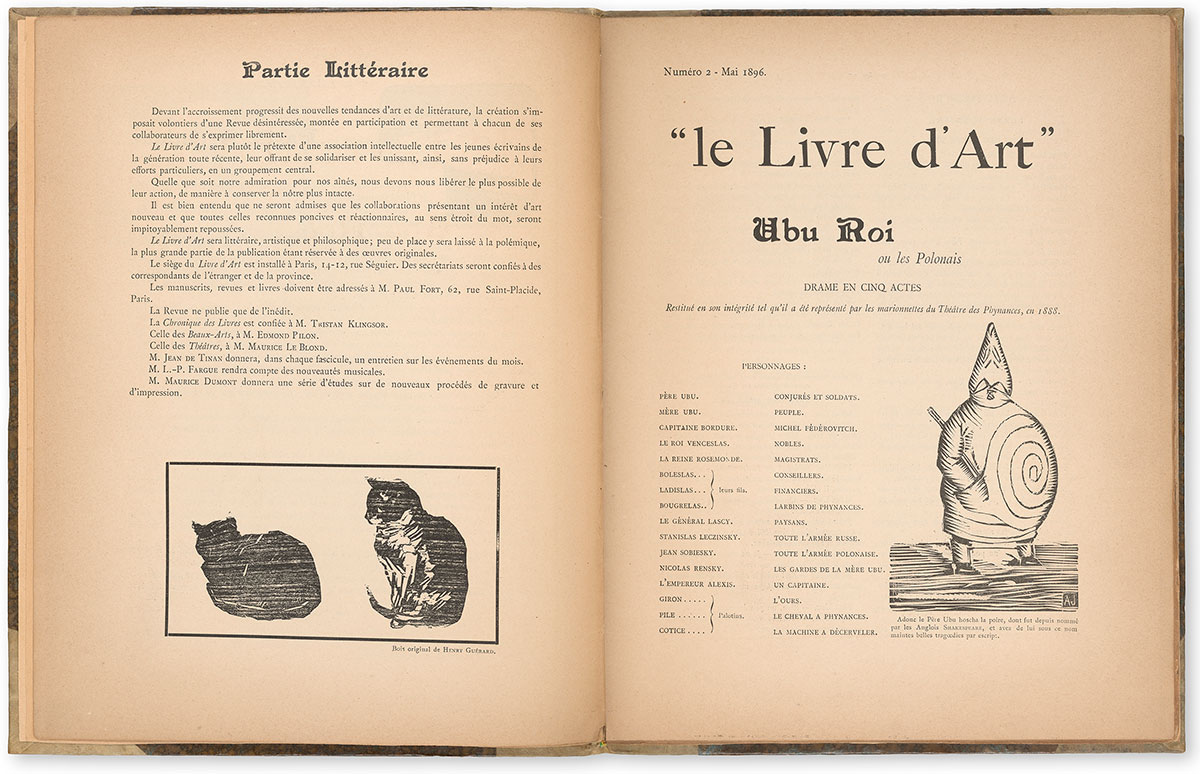

Livre d’Art

The woodcut portrait of Ubu that Jarry used as the book’s frontispiece was starkly modern in contrast with the book’s design. It had already appeared

The woodcut portrait of Ubu that Jarry used as the book’s frontispiece was starkly modern in contrast with the book’s design. It had already appeared

in the play's serialization in an avant-garde magazine that promoted the artistic revival of the woodcut.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), “Ubu roi,” in Livre d’Art no. 2 (April 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197088.

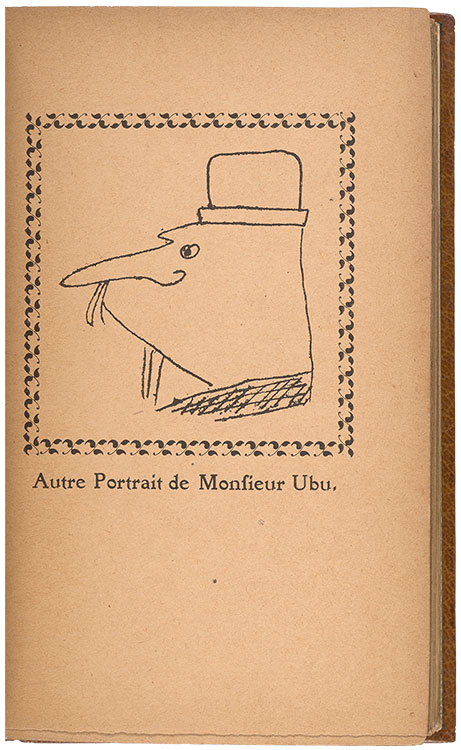

Autre Portrait de Monsieur Ubu

When Jarry reprinted the crude woodcut in the first edition, he also added this second portrait—a more cartoonish image of Ubu. That the images looked nothing alike introduced the pataphysical concept of the equivalence of opposites into the realm of contemporary illustration.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197019.

Ubu roi, texte et musique

Jarry capitalized on Ubu roi’s notoriety by issuing a facsimile of the manuscript the following year. For the edition, he rendered in pen and ink the text, title, and every ornament as well as his two portraits of Ubu. He also incorporated Claude Terrasse’s incidental music and shared credit with the composer on the cover. Jarry used the opportunity to describe his ambitious plans for an orchestra—which, in performance, had amounted to little more than a piano and some timpani.

Of his cycle of full-length plays—Ubu roi, Ubu enchaîné, and Ubu cocu—only the first was performed during Jarry’s lifetime. Ubu enchaîné was published in 1900, however, as an addendum to the second edition of Ubu roi. This version bore no traces of Jarry’s idiosyncratic illustrations or inventive book design. By that point, Jarry had switched publishers and had ceded the role of Ubu’s iconographer to Terrasse’s brother-in-law, the painter Pierre Bonnard.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Claude Terrasse (1867–1923), Ubu roi, texte et musique, facsimile autographique (Paris: Mercure de France, 1897). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197020.

L'amour absolu: roman

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the practice of publishing facsimiles of manuscripts became a trend for Symbolist writers. The movement’s chief poet, Stéphane Mallarmé, had issued his manuscript of Poésies in a photo-lithographed edition of 40 copies in 1887. Jarry’s friends Rachilde, Marcel Schwob, and Remy de Gourmont followed suit. When Jarry could not find a publisher for L’Amour absolu, he paid to produce his novel in this fashion in an edition of fifty copies.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), L'amour absolu: roman ([Paris: Mercure de France, 1899]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197024.

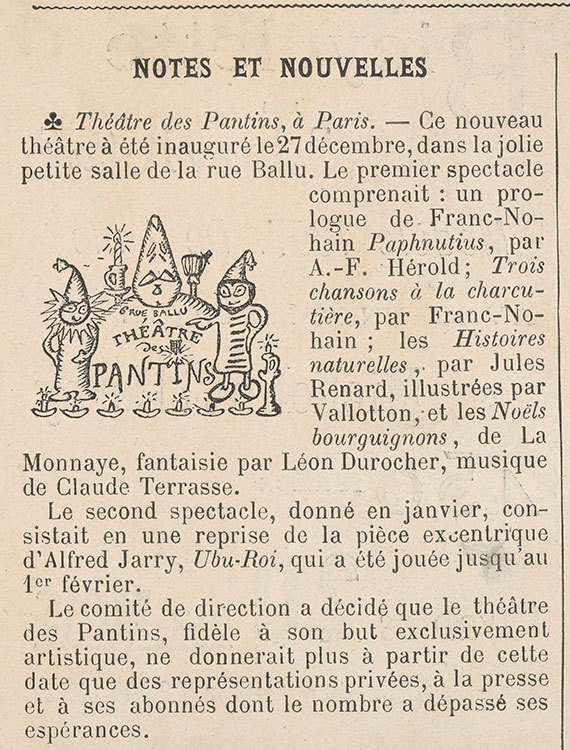

Théâtre des Pantins

"Notes et nouvelles: Théâtre des Pantins, à Paris," Revue encyclopédique Larousse (5 fév. 1898), p. [9]. Private collection.

Théâtre des Pantins

Jarry adapted Ubu roi for an avant-garde marionette theater he cofounded in 1897 with the painter Pierre Bonnard, the composer Claude Terrasse, and the writers Franc-Nohain and A.-F. Herold. The Théâtre des Pantins mounted their shows in the atelier behind Terrasse’s house. Edouard Vuillard and Bonnard painted the walls and Jarry and Franc-Nohain acted as chief puppeteers. Bonnard also built the marionettes with the exception of Ubu, which Jarry created himself.

Censorship had not been an issue at the Œuvre because it was a subscribers’ theater. The Pantins was open to the public, however, so the company had to submit the script to a bureaucrat for review (predictably, his scatological neologism “merdre” was cut). This shorter version of Ubu roi for marionettes was never published. There were three performances.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), program for Ubu roi at the Théâtre des Pantins, 1898, lithograph. Collection Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University. Museum Purchase, David A. and Mildred H. Morse Art Acquisition Fund. Photography by Peter Jacobs

Marionettes

Photographs of the marionette of Ubu created by Charlotte Jarry (1865–1925), ca. 1888-89, in Les soirées de Paris, no. 24 (1914). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197215.

Marionettes

Marionettes created by Alfred Jarry and Pierre Bonnard for the Théâtre des Pantins, ca. 1897–98. Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet, Paris.

Marionettes created by Alfred Jarry and Pierre Bonnard for the Théâtre des Pantins, ca. 1897–98. Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet, Paris.

Ouverture d’Ubu roi

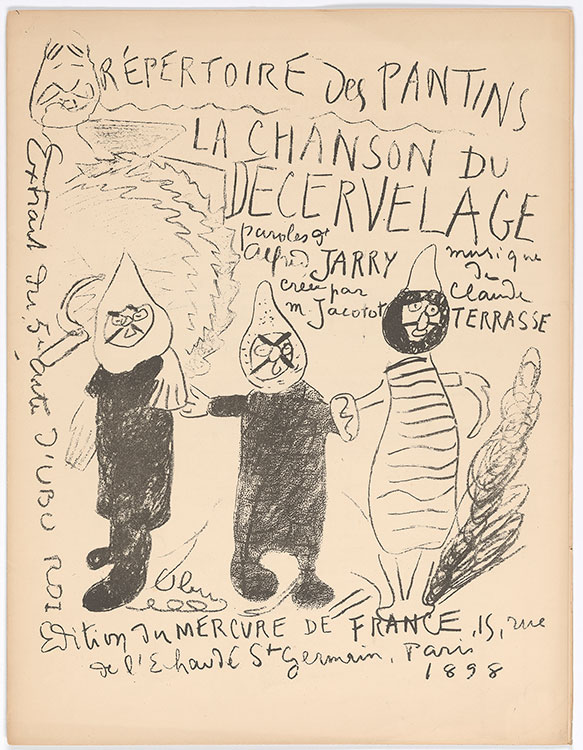

Claude Terrasse’s incidental music for the Théâtre des Pantins’ puppet shows outlasted the short-lived endeavor. Individual songs were issued as sheet music with striking lithographed covers designed by Jarry and Bonnard.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Claude Terrasse (1867–1923), Répertoire des Pantins: Ouverture d’Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1898). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197089.

Marche des polonais

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Claude Terrasse (1867–1923), Répertoire des Pantins: Marche des polonais (Paris: Mercure de France, 1898). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197090.

La chanson du décervelage

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Claude Terrasse (1867–1923), Répertoire des Pantins: La chanson du décervelage (Paris: Mercure de France, 1898). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197091.

Ubu sur la butte

After the Théâtre des Pantins folded, Jarry adapted the play yet again for low-brow hand puppets at the rowdy Cabaret des Quat’z’arts in Montmartre. Ubu sur la butte, as he later titled it, ran for sixty-four performances in 1901. For the scenario, Jarry cannibalized Ubu roi to reduce the play to two acts. The substantial changes he made reflected his anticipation of censorship and respect for the cabaret milieu. Like most puppet shows, the new version breached the fourth wall with a dialogue between the director and the archetypal puppet Guignol, who also referenced the cabaret and its spectators.

Five years later, Jarry published Ubu sur la butte as part of his booklet series he called Théâtre mirlitonesque—a term comparable to “ridiculous theater.” For the title page and cover designs, he copied the architectural frame on the 1535 title page of François Rabelais’s Gargantua—published in Lyon, the birthplace of the hand-puppet tradition—but used mirlitons, which are a kind of kazoo, in place of Rabelais’s classic columns.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu sur la butte, Théâtre mirlitonesque (Paris: Sansot et Cie, 1906). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197031.

Le moutardier du pape

Over a decade, Jarry composed librettos for at least ten operettas. Most remained unfinished or were printed posthumously. Par la taille would be the second and last title to appear in Jarry’s whimsical Théâtre mirlitonesque book series in 1906. In 1907, his friends helped organize a deluxe publication of his comic opera Le moutardier du pape—a farcical retelling of the legend of Pope Joan, who disguised herself as a man. The book’s design united a pensive (much younger) portrait of Jarry with eleven-year-old images of Ubu, who has no role in the operetta.

Similar to Jarry’s ahistorical approach to book design, his comic operas contain anachronistic figures and technologies. Photography and the Salvation Army are invoked within the ninth-century setting of Le moutardier, which also features a telephone. The title character tells Joan he is going to make a call “without a line,” adding, “for the time being, pending its invention.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Le moutardier du pape: Opérette bouffe en trois actes (Paris: s.n., 1907). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197034.

Pantagruel

Characters in Jarry’s comic operas are empty vessels, similar to marionettes. As one scholar phrased it, the subject of these librettos is arguably language itself. Jarry’s paragon in the linguistic arts was François Rabelais. For eight years, Jarry labored to turn Rabelais’s Pantagruel into an operetta. By 1904, however, his health had declined, exacerbated by alcoholism and poverty. Pantagruel’s composer, Claude Terrasse, persistently pressed Jarry to make progress on the libretto. He lured the writer to his country house to help him dry out and finish the text, but neither plan was successful (a friend completed the libretto after Jarry’s death). The fanciful baroque sets and costumes used in its 1911 premiere proved to be the antithesis of the anti-naturalist mise-en-scène that defined Jarry’s career.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Eugène Demolder (1862–1919), Pantagruel: Opéra-bouffe en cinq actes et six tableaux, musique de Claude Terrasse (Paris: Société d’éditions musicales, 1911). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197036.

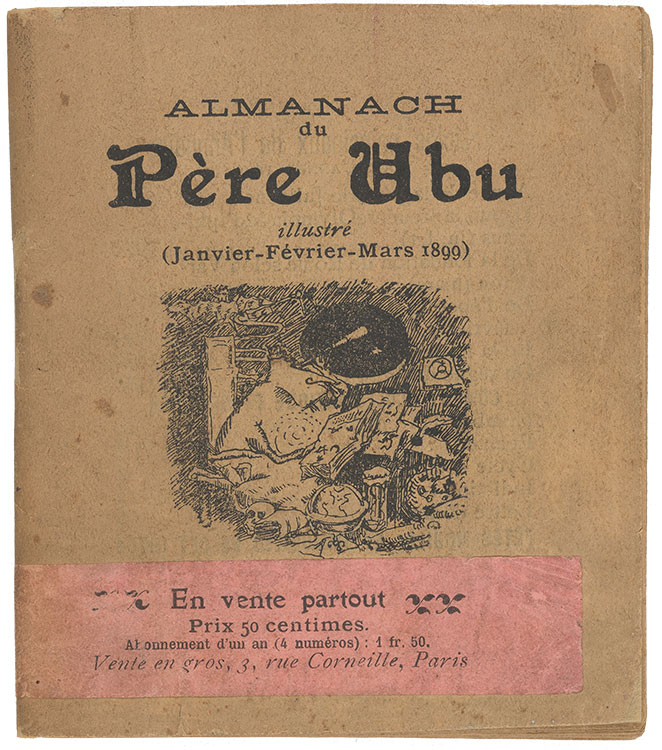

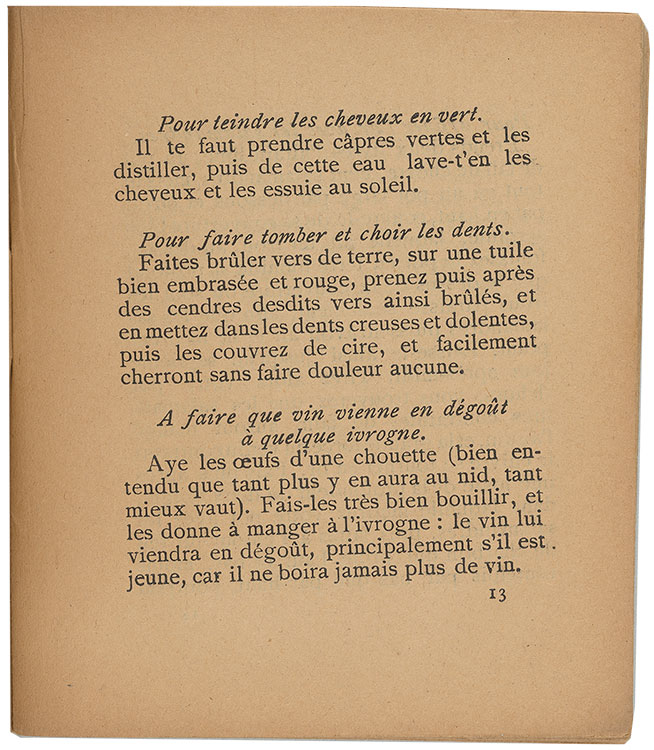

Almanach du Père Ubu illustré

Ubu returned to print for Jarry’s reinvention of a centuries-old genre: the common almanac. Both the author and the illustrator, Pierre Bonnard, were uncredited. Jarry applied his own approach to illustration when composing the texts by assembling original material with passages appropriated from old books. There were new playlets as well as sixteenth-century recipes for dyeing one’s hair green (supposedly something Jarry himself did on one occasion). The religious calendars—a requisite of early almanacs—listed the feast dates celebrating genuine saints as well as Saint Merdre. Another requisite of the genre, astronomical forecasts, predicted a partial “eclipse of Père Ubu.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach du Père Ubu illustré. Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: s.n., [1898]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197025.

Almanach du Père Ubu illustré

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach du Père Ubu illustré. Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: s.n., [1898]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197025.

Almanach du Père Ubu illustré

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach du Père Ubu illustré. Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: s.n., [1898]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197025.

Almanach du Père Ubu illustré

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach du Père Ubu illustré. Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: s.n., [1898]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197025.

Île du Diable

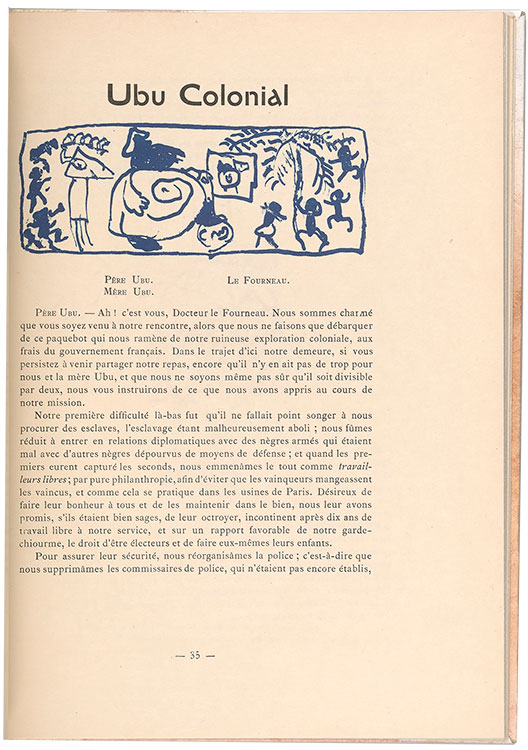

Jarry’s most overt political commentary surfaces in the Ubu almanacs. The play Île du Diable (Devil’s Island), included in the first almanac, dramatizes events related to the Dreyfus affair. Ubu is cast as an effigy of the corrupt French military. The character would stand in as a proxy for France itself in the second almanac’s Ubu colonial, which comprises an account of Ubu’s visit to Africa. Jarry’s satire of the attitudes informing colonial practices was always indiscriminate, ridiculing both the perpetrators and victims of colonialism—an ambivalence affirmed by Bonnard’s offensive caricatures.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach du Père Ubu illustré. Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: s.n., [1898]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197025.

Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle), cover

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, cover. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle), pp.42-43

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, pp.42-43. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, pp.42-43. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle), p. 35

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, p. 35. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle), pp.14–15

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, pp. 14–15. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

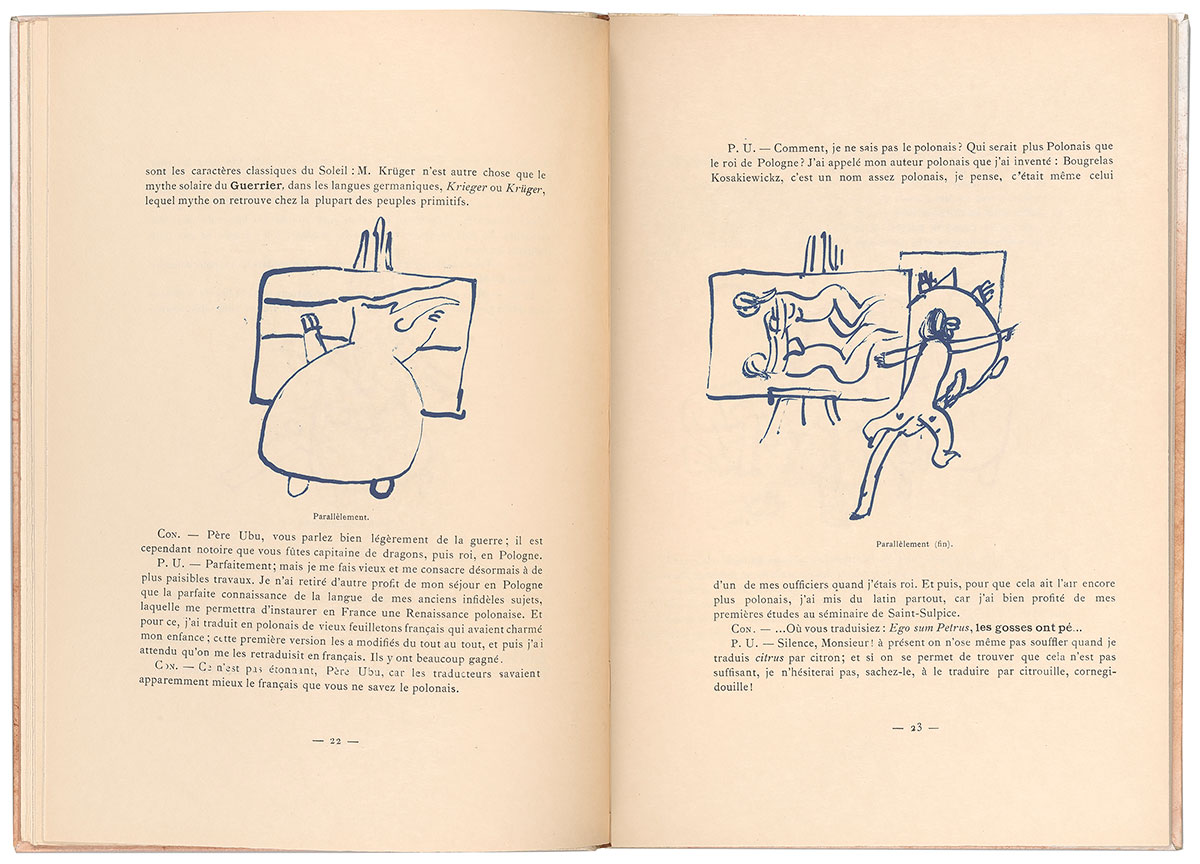

Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle), pp. 22–23

The 1901 almanac was produced in a luxurious edition, a first for Jarry. This collaborative enterprise between Jarry, Bonnard, and other friends took shape in the basement of Ambroise Vollard’s modern art gallery. The influential dealer (also the almanac’s anonymous publisher) had just begun to conceive deluxe illustrated books of poetry, now called livres d’artistes, as promotional materials for contemporary artists. Vollard’s first such project, Paul Verlaine’s Parallèlement (1900), was a showcase for Bonnard’s sensual lithographs. Jarry and the painter mocked its scandalous imagery in one of the almanac’s episodes; they also created their own suggestive text and images for several letters in “Ubu’s Alphabet.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, pp. 22–23. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.