The Pataphysics of the Book

Jarry introduced the term “pataphysics” in 1893. He presented it as a given—as if pataphysics was the mother of the invention of pataphysics. Another given, according to Jarry, was that opposites are equivalent. Later, he would write that pataphysics is “the science of imaginary solutions,” concerned with laws that govern exceptions (the particular, rather than the general); it explains the universe supplementary to this one—or, at least, it describes a universe that could and perhaps should be envisioned in place of our own. Unconstrained by time, pataphysics dwells in Eternity and in the imagination of the artist.“God—or myself—created all possible worlds,” wrote Jarry.

The imaginative universe of Jarry’s book and magazine design reflects these pataphysical notions as well as the unfettered nonconformity he brought to bear on all aspects of his life. As proponents of the art of the book attempted to recapture the past, Jarry renovated publishing as an artistic practice. In place of the unity of text, illustration, and type, he welcomed disjointedness and anachronisms, while co-opting existing words and images as his own.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Books figure as hallucinatory or apocalyptic metaphors in Jarry’s writings. He rarely reflected on the subject in essays other than to mock the uniformity of French book covers. Jarry’s first cover designs were chiefly black, with no title or author, just a small heraldic symbol printed in gold. For the special editions, he used medieval imagery from the Ars memorandi (The Art of Memory).

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

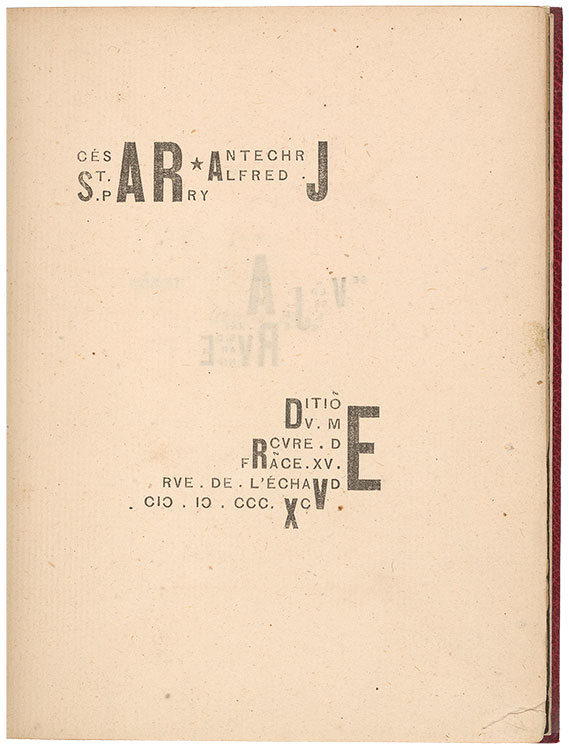

César-antechrist

Now, I had in my hands—since when?—a book—certainly written by me; how and when? no memory— where all that I was to see, all that I was to think afterwards, was foretold. . . . And the letters were pictures.

—Alfred Jarry, “Opium” (1893)

Jarry privileged painting over writing. Images, he argued, can be perceived all at once, whereas writing is sequential and thus constrained by duration. This title-page design defies the linearity of reading, however, presenting itself as both image and information. Some letters operate in multiple words; others are unstable (a J can be an I or a Y). Jarry’s use of medieval tildes (as in Frãce for France) requires the reader to complete the words.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

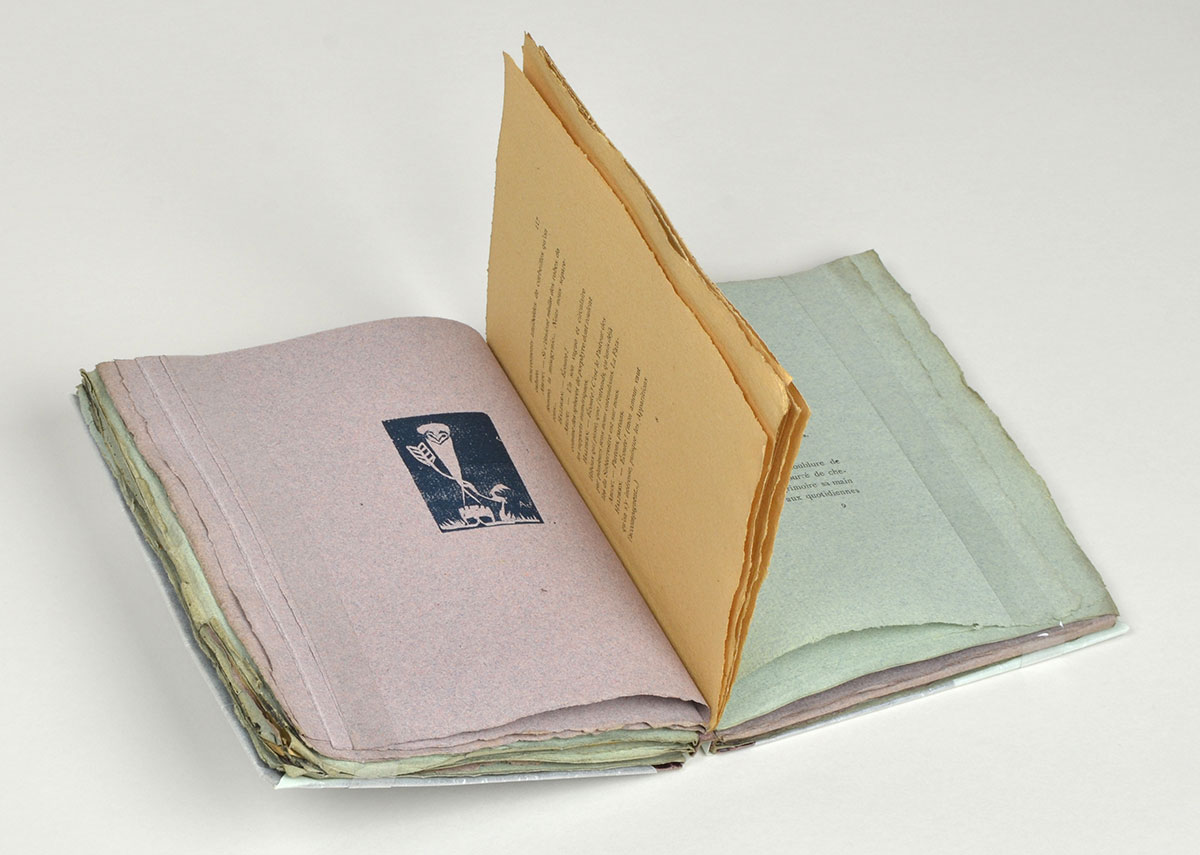

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Jarry’s first publication, Les minutes de sable mémorial, was a collection of poetry, prose, and plays (some were written for puppets). Many pieces by the twenty-one-year-old had appeared previously in avant-garde magazines. His creative approach to the interplay of text and image was unprecedented, however. The Symbolist writer and critic Remy de Gourmont mentored Jarry in the art of the book. As the unofficial artistic director of the magazine Mercure de France and its imprint, Gourmont had established a house style that was both modern and medieval, informed by advertising and the aesthetics of early printing. Jarry absorbed his mentor’s taste and used it as a point of departure for his experimental designs, going so far on two occasions as to produce a book on three different-colored papers.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). Collection of Christophe Champion, Librairie Faustroll.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

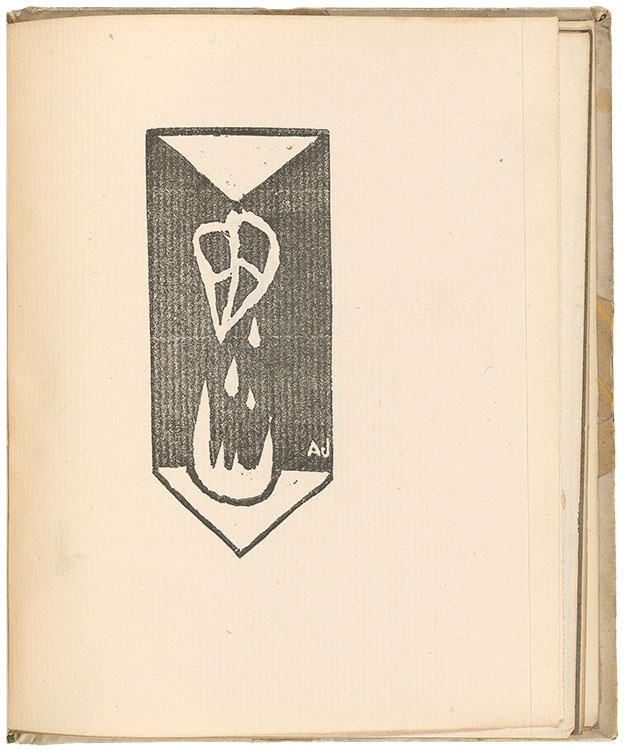

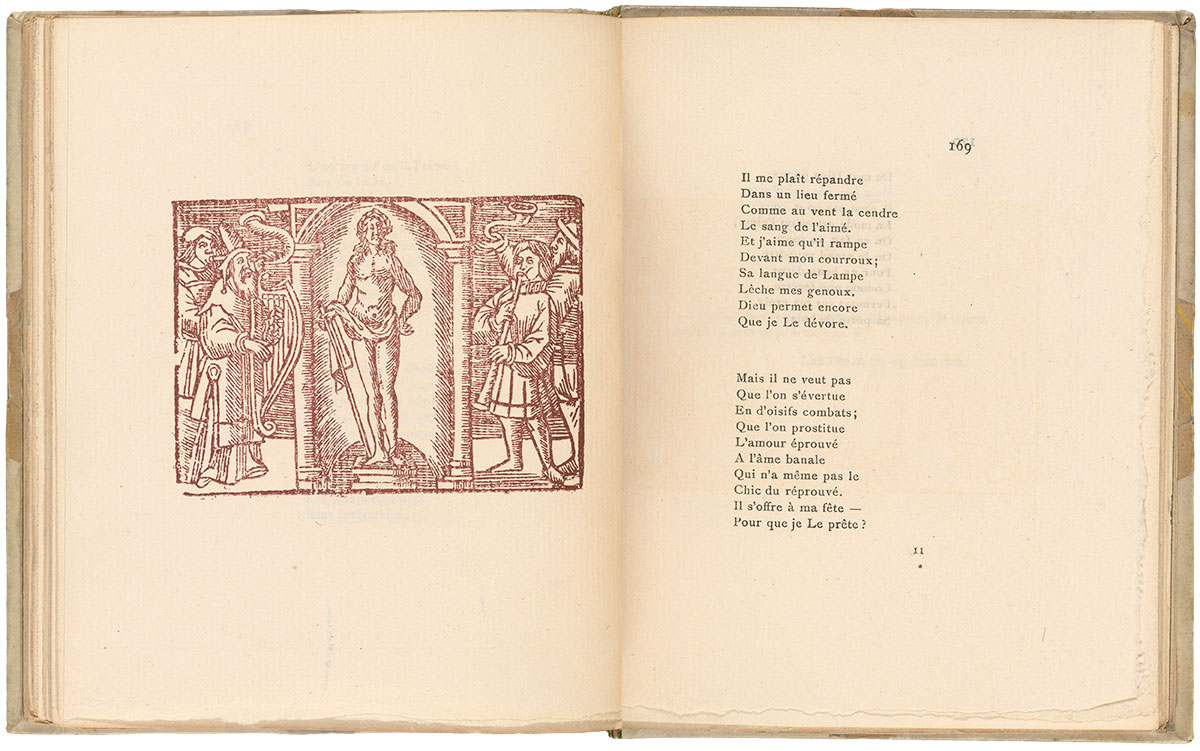

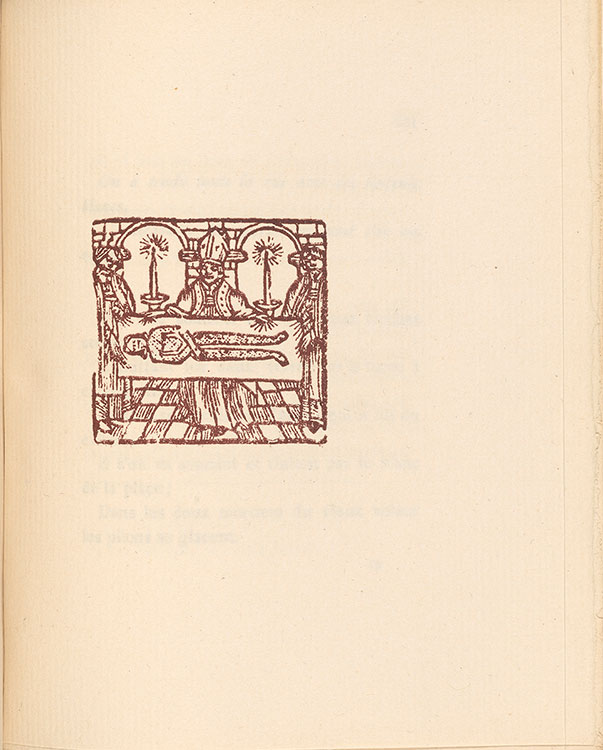

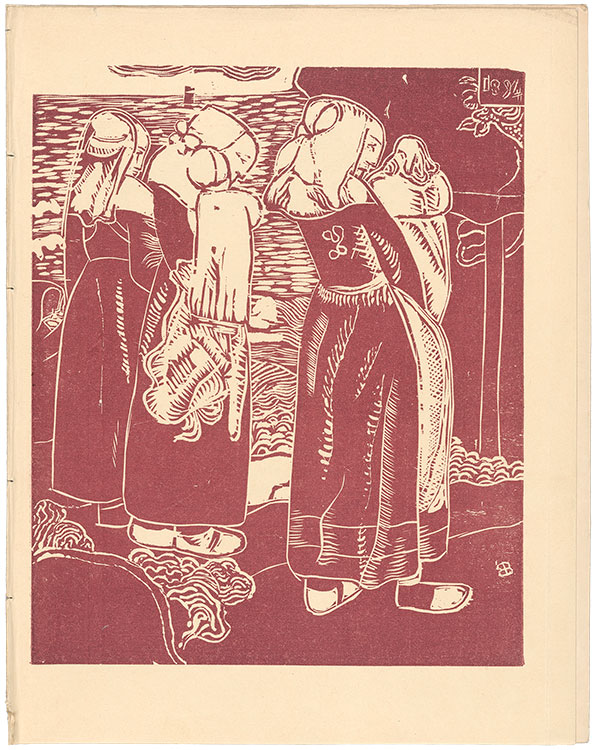

The woodcut illustrations Jarry began to create in 1894 around the artists at Pont-Aven combined a crude modern aesthetic with primitive imagery he came across in old religious prints. Unlike his contemporaries, he made no attempt to unify the disparate designs within his early books. Claustrophobic arrangements of ornaments, obscure forms, occult symbols and other designs that verge on abstraction were melded into one visual vocabulary.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017

César-antechrist

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

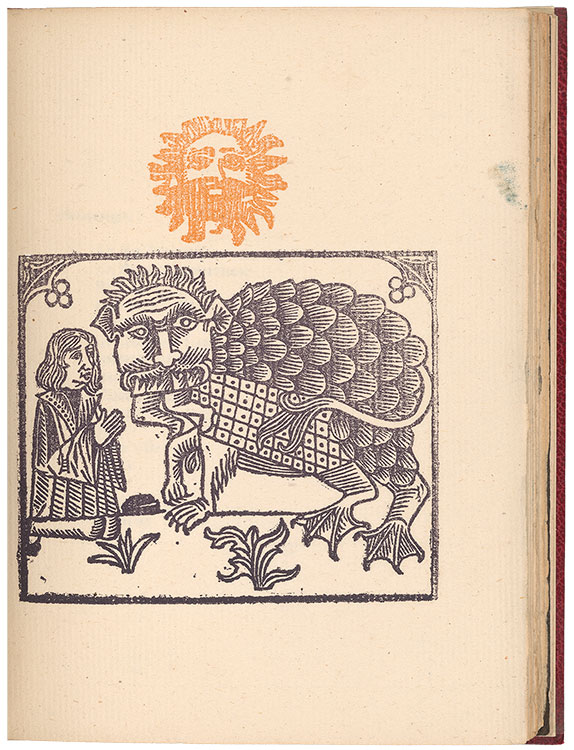

César-antechrist

In his early books, Jarry interspersed his own woodcuts (or line drawings he passed off as woodcuts) with found imagery. This illustration for his second book is a composite design of two Renaissance woodcuts. He appropriated most of these kinds of woodcuts from an old catalogue documenting four centuries of popular imagery. Their unacknowledged presence in tandem with Jarry’s modern literature and design seemed to resituate the past in the contemporary or, conversely, suggested that Jarry’s work is itself anachronous. His engagement with both the Middle Ages and the modern shares traits with Baudelaire’s definition of beauty and ideas suggested by Nietzsche’s Meditations on the Untimely; but Jarry fractured this unity in the realm of the book arts. Such disharmony was at odds with figures such as William Morris who were attempting to unify book design in ways that reflected Richard Wagner’s concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

César-antechrist

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

César-antechrist

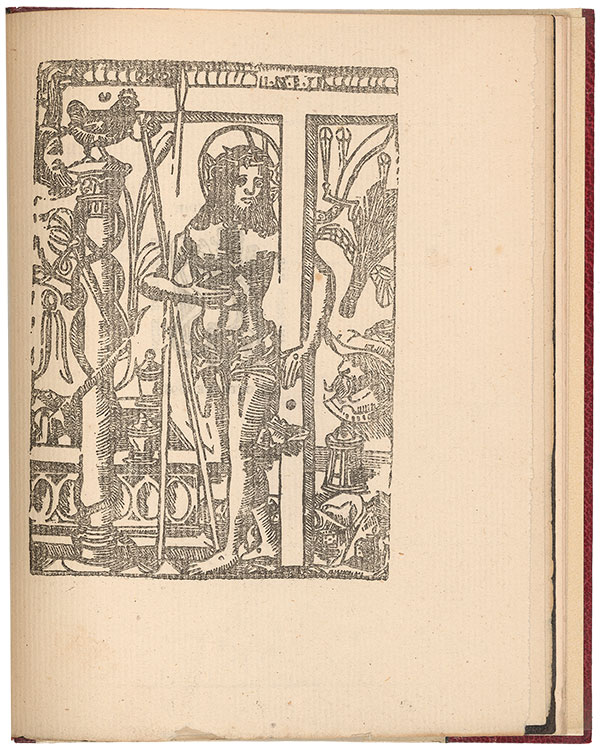

The privileging of found imagery over original designs became more pronounced in Jarry’s second book. This frontispiece, which is one of only two original illustrations in his apocalyptic drama César-antechrist, is something of a hybrid. Jarry chose elements from multiple woodcut illustrations in a popular renaissance series of papal prophecies; he rearranged them and added hand-drawn elements to his busy design. By merging a catalogue of images into one pictorial field, Jarry’s collage suggests a Cubist approach to “reading” an illustrated book on one page.

The privileging of found imagery over original designs became more pronounced in Jarry’s second book. This frontispiece, which is one of only two original illustrations in his apocalyptic drama César-antechrist, is something of a hybrid. Jarry chose elements from multiple woodcut illustrations in a popular renaissance series of papal prophecies; he rearranged them and added hand-drawn elements to his busy design. By merging a catalogue of images into one pictorial field, Jarry’s collage suggests a Cubist approach to “reading” an illustrated book on one page.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

Source imagery, Prophetia dello abbate Joachino circa li Pontifici [et] R.E. (Venice: Niccolò & Domenico dal Gesù, 1527),The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1925. PML 23177.

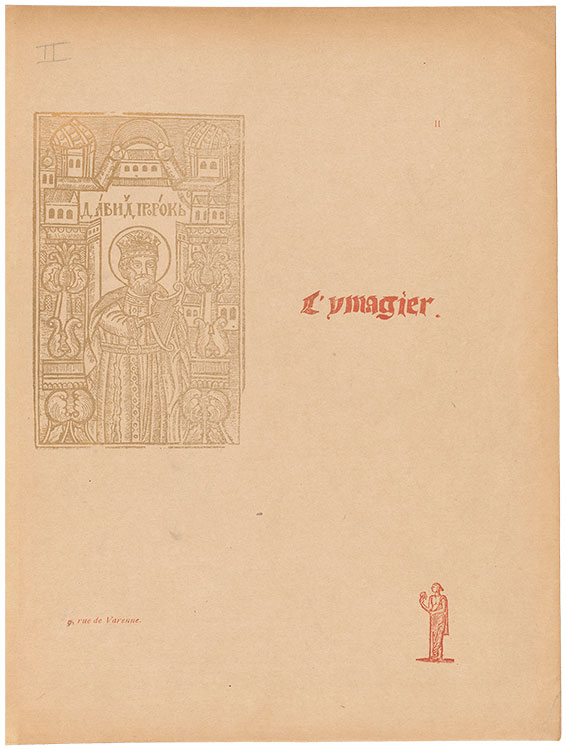

L’Ymagier

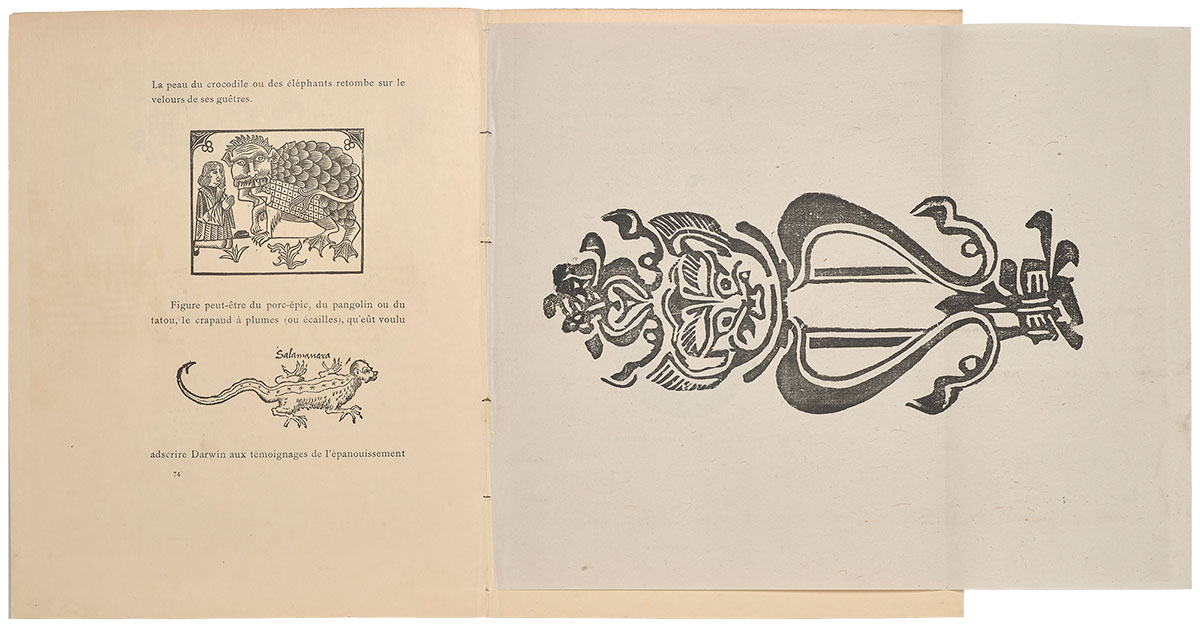

Jarry’s first magazine, L’Ymagier (1894-96), which he coedited with Remy de Gourmont, reversed the traditional separation of disparate forms, genres, and artistic periods. As a kind of radical museum in print, the magazine not only proposed equivalence across modern history and high and low culture but also questioned the distinction between original and copy. Gourmont and Jarry each contributed a few prints of their own usually under pseudonyms. Most of their contributions, however, were essays and commentaries on visual iconography over time. The chimerical, time-bending aesthetic of the magazine conformed to Jarry’s inverted definition of beauty in the second issue, which defined the monstrous as “all original, inexhaustible beauty.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Remy de Gourmont (1858–1915), eds., L’Ymagier no. 2 (1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

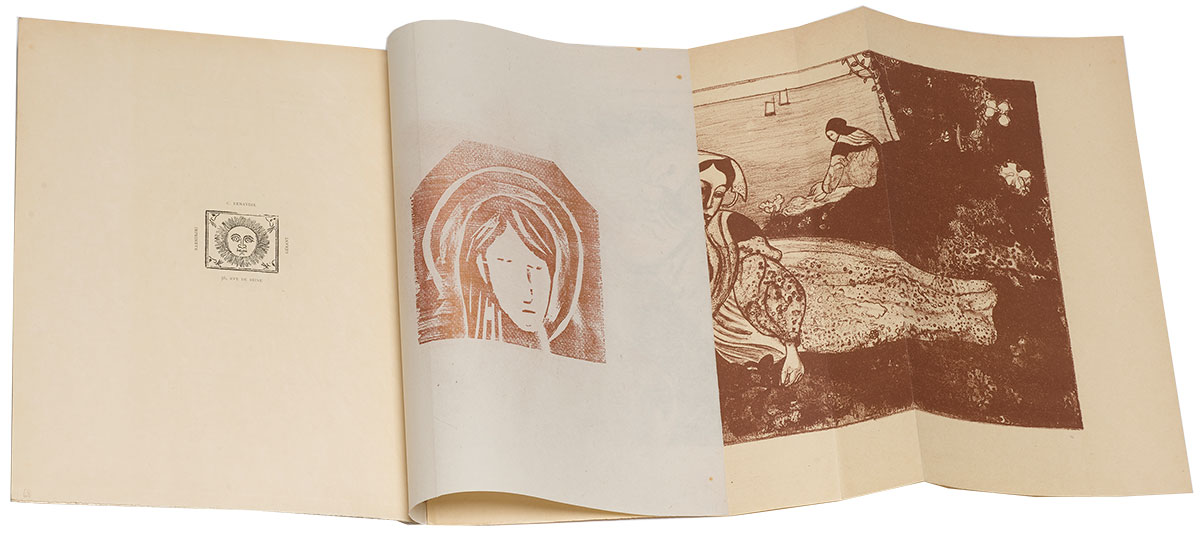

Sainte Madeleine

Many of the prints in L’Ymagier were reproduced on sliver-thin exotic or colored papers that, when folded, might open vertically, horizontally, or both. Contemporary prints by several of the artists he knew in Pont-Aven—including Charles Filiger, Paul Gauguin, Armand Séguin, and Roderic O’Conor—and other painters he admired, such as Émile Bernard and Henri Rousseau, were collated with Renaissance and folkloric imagery, Épinal prints, facsimiles of early typography, and non-Western art.

Found imagery, Remy de Gourmont (1858–1915), Sainte Madeleine, wood engraving, and Armand Séguin (1869–1903), Femme couchée, zincograph, in L’Ymagier, no. 2 (January 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

“Les Monstres”

Found imagery and Southeast Asian woodcut, in Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), “Les Monstres,” in L’Ymagier no. 2 (January 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

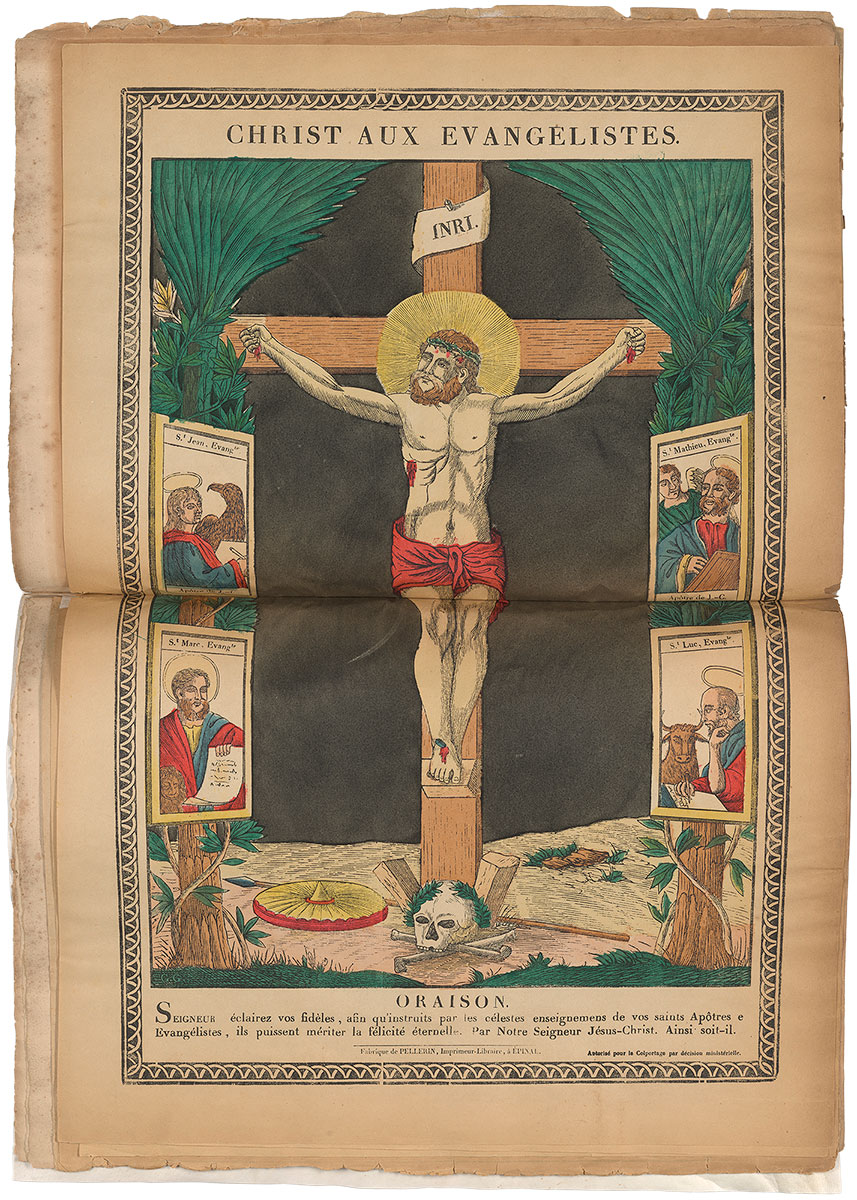

Jésus sur la croix

Large Épinal prints were folded and bound directly into the magazine. These cheap color-stenciled woodcuts were still available in bookstalls along the Seine, but their primitive quality belonged to an earlier part of the nineteenth century. By the 1890s, the Pellerin firm was reproducing the woodcuts using photomechanical processes. Jarry and Gourmont commissioned hundreds of copies to include in L’Ymagier. In essays relating to the iconography and history of the woodcut, the editors lauded the most famous engraver of Épinal prints, François Georgin, as a master worthy of comparison to Albrecht Dürer.

François Georgin (1801–1863), Jésus sur la croix, Épinal print, 1824, reprinted by the Pellerin firm, in L’Ymagier, no. 1 (October 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. And Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Notre-Dame des Ermites

François Georgin (1801–1863), Notre-Dame des Ermites, Épinal print, 1824, reprinted by the Pellerin firm, in L’Ymagier, no. 3 (April 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. And Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Le Miroir du pécheur

François Georgin (1801–1863), Le Miroir du pécheur, Épinal print, 1825, reprinted by the Pellerin firm, in L’Ymagier, no. 1 (October 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. And Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Vierge à l’enfant

Charles Filiger (1863–1928), Vierge à l’enfant (also known as Ora pro nobis), photomechanical print with added hand stenciling, in L’Ymagier, no. 1 (October 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Bretonnes

Armand Séguin (1869–1903), Bretonnes, reproduction of a woodcut, in L’Ymagier, no. 2 (January 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

L’Ymagier, no. 1

L’Ymagier, no. 1 (October 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Monstrorum historia

Reproduction of a woodcut from Ulisse Aldrovandi, Monstrorum historia (Bologna: Nicolai Tebaldini, 1642), in L’Ymagier, no. 5 (October 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197082.

César-antechrist in L’Ymagier

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist, lithograph, in L’Ymagier, no. 2 (January 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Henri Rousseau

Of H. Rousseau: there is above all “War (terrifying, she passes . . . ).” With legs outstretched the horror- struck steed stretches its neck with its dancer’s head, black leaves inhabit the mauve clouds, and bits of debris fall like pine cones among the translucent corpses of axolotls attacked by bright-beaked crows.

—Alfred Jarry, “Minutes d’art,” 1894

In his singular, independent approach to life and art, Henri Rousseau, much like Jarry, was viewed as sui generis. The painter was also a native of Jarry’s hometown, Laval. They were nearly thirty years apart in age and did not meet until 1894 in Paris. Few artifacts survive attesting to their friendship, although they lived together briefly.

Rousseau’s painting La guerre was the subject of ridicule when it was exhibited in 1894 at the Salon des Indépendants, but it made a significant impact on the twenty-year-old Jarry and inaugurated their friendship. Jarry wrote about the work in two separate articles and also commissioned Rousseau to create a lithograph based on the painting. Jarry’s immediate recognition of Rousseau’s talent and their compatibility became the stuff of legend: Guillaume Apollinaire and others spread apocryphal stories that Jarry “discovered” Rousseau and assigned him the nickname “Le Douanier” (the customs officer).

Henri Rousseau (1844–1910), La guerre, ca. 1894, oil on canvas. Paris, musée d’Orsay. © RMN-Grand Palais / Erich Lessing/ Art Resource, N.Y.

La guerre in L’Ymagier

Rousseau’s only lithograph was the one he created after his painting La guerre expressly for L’Ymagier. He made significant changes to the figures and the landscape, suggestive of the naive popular imagery the magazine often featured. Rousseau also painted a portrait of Jarry (now lost) that was listed in the catalogue for the Salon des Indépendants in 1895 as Portrait de Madame A.J.

Rousseau’s only lithograph was the one he created after his painting La guerre expressly for L’Ymagier. He made significant changes to the figures and the landscape, suggestive of the naive popular imagery the magazine often featured. Rousseau also painted a portrait of Jarry (now lost) that was listed in the catalogue for the Salon des Indépendants in 1895 as Portrait de Madame A.J.

Henri Rousseau (1844–1910), La guerre, lithograph, in L’Ymagier, no. 2 (January 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

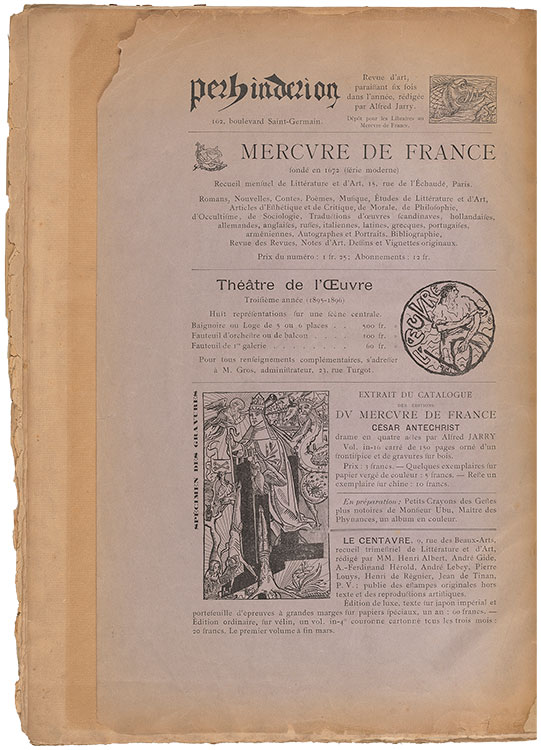

Perhinderion

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), ed., Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

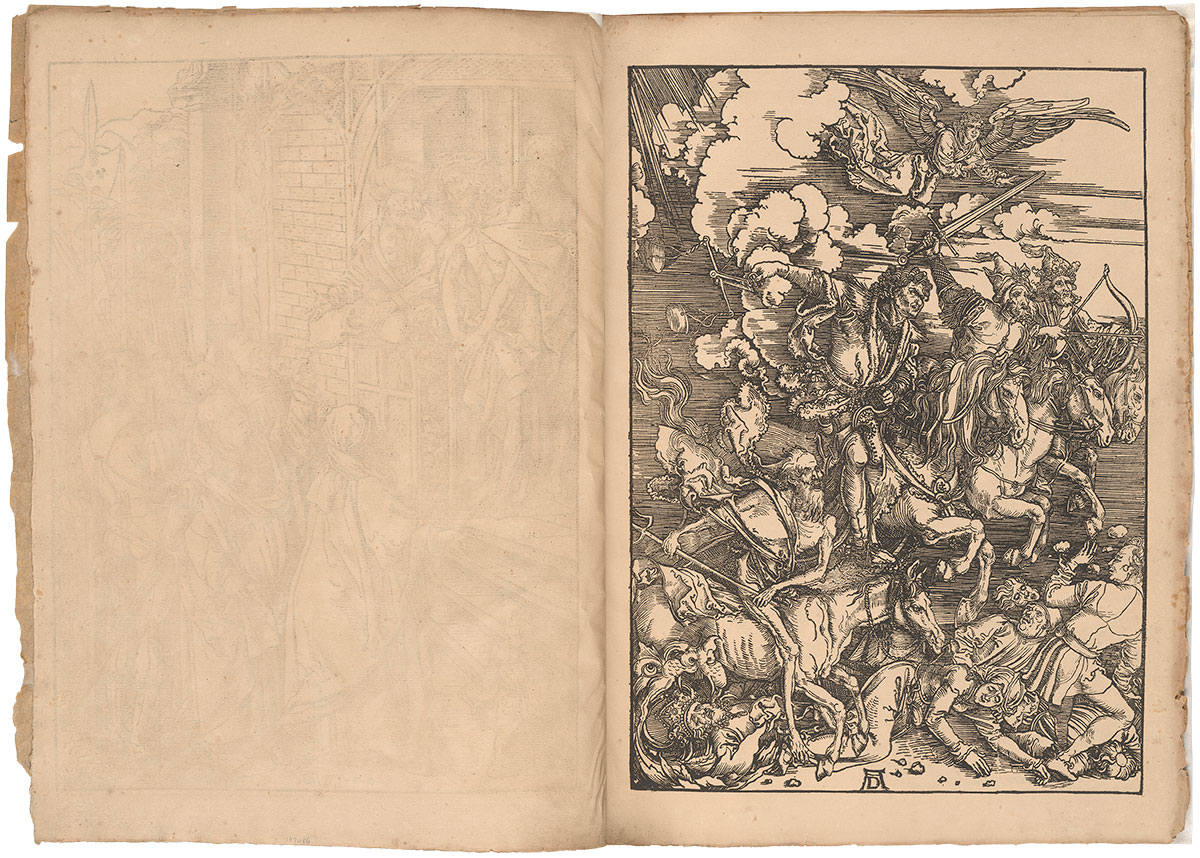

The Four Horsemen

Jarry’s collaborations and friendship with Remy de Gourmont ended due to a prank Jarry and his friends played on his mentor’s mistress. After five issues of L’Ymagier (which was largely bankrolled by the mistress), he started his own magazine: Perhinderion. The title is a Breton word for “pilgrimages.” In his editorial statement, Jarry compared himself to the simple men who peddled religious keepsakes to the devout masses. Jarry was much more ambitious, however. It was his intention to publish Albrecht Dürer’s complete works in the magazine over time. The expense of the luxurious venture exhausted his finances after two issues.

Jarry’s collaborations and friendship with Remy de Gourmont ended due to a prank Jarry and his friends played on his mentor’s mistress. After five issues of L’Ymagier (which was largely bankrolled by the mistress), he started his own magazine: Perhinderion. The title is a Breton word for “pilgrimages.” In his editorial statement, Jarry compared himself to the simple men who peddled religious keepsakes to the devout masses. Jarry was much more ambitious, however. It was his intention to publish Albrecht Dürer’s complete works in the magazine over time. The expense of the luxurious venture exhausted his finances after two issues.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Four Horsemen, from The Apocalypse, 1498, in Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

Christ aux Evangelistes

François Georgin (1801–1863), Christ aux Evangelistes, Épinal print, ca. 1827, in Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

Passage du Mont Saint-Bernard

François Georgin (1801–1863), Passage du Mont Saint-Bernard, Épinal print, ca. 1831, in Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

François Georgin (1801–1863), Passage du Mont Saint-Bernard, Épinal print, ca. 1831, in Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

Le Juif-errant

François Georgin (1801–1863), Le Juif-errant, Épinal print, ca. 1826, in Perhinderion no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

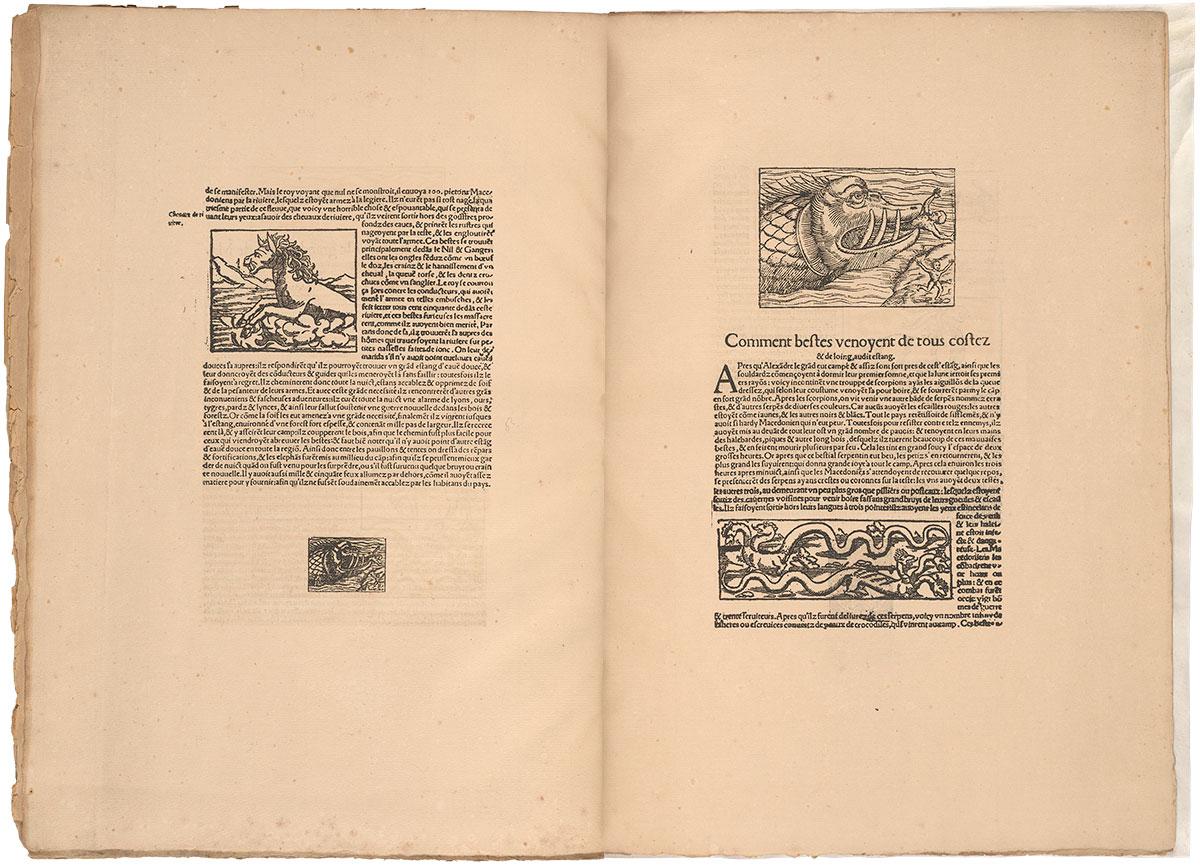

La cosmographie universelle

By 1896, Jarry had been experimenting for two years with composite illustrations and with the integration of found imagery and original woodcuts. He had sometimes passed off his own primitive drawings and prints as woodcuts; he had recycled imagery in multiple publications and pursued his interest in early typography; and he had used the practice of assembling texts and images to create new conceptions of printed matter. These early investigations persisted in Perhinderion using almost no original content of his own. Jarry’s creative gestures registered indirectly, however. This spread appears to be a facsimile. It is actually a collage of multiple pages Jarry chose from a sixteenth-century book.

Composite page designs based on Sebastian Münster’s La cosmographie universelle (1552), in Perhinderion, no. 1 (March 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

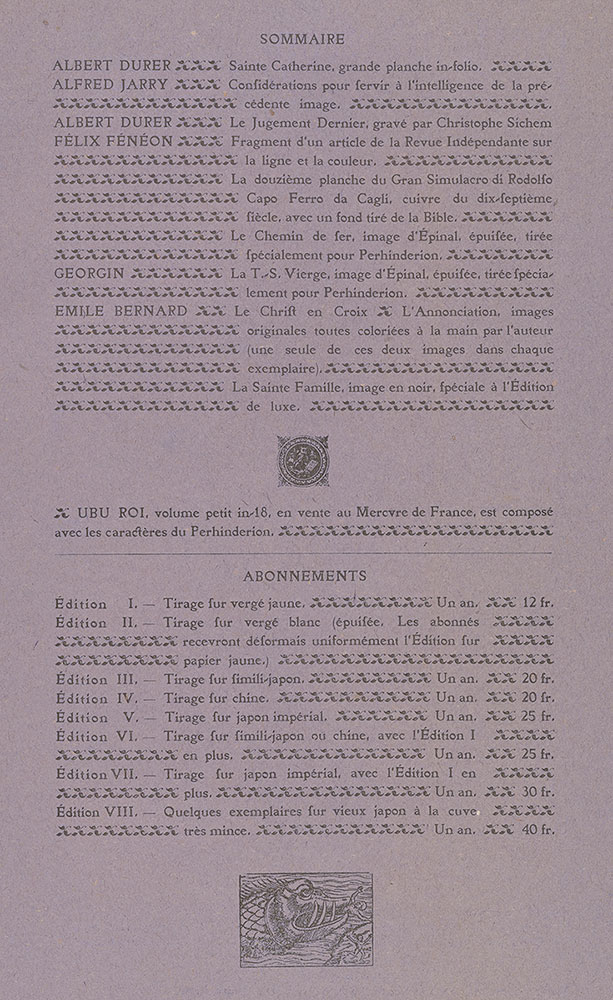

Perhinderion, no. 1

Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

Perhinderion, no. 2

Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

The Martyrdom of St. Catherine of Alexandria

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Martyrdom of St. Catherine of Alexandria, n.d., in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

“Considérations pour server à l’intelligence de la précédente image”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), “Considérations pour server à l’intelligence de la précédente image,” in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

La très sainte Vierge

François Georgin (1801–1863), La très sainte Vierge, Épinal print, 1837, in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

Le chemin de fer

Unidentified artist, Le chemin de fer, Épinal print, 1838, in Perhinderion no. 2 (June 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

Unidentified artist, Le chemin de fer, Épinal print, 1838, in Perhinderion no. 2 (June 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

D’Art

This page contains an extract from Édouard Dujardin’s influential essay from 1888, titled “Cloisonnism.” Jarry chose the passage in which Dujardin argued that the source of an artist’s imagery, be it a Japanese or Épinal print, is insignificant in comparison to the purpose the image serves for an artist’s project. Jarry set the text in the Renaissance-style type he had acquired and named for Perhinderion. The antiquated letterforms and punctuation include the long s, which resembles f, and ligatures; Jarry replaced Dujardin’s semicolons with colons, as if to connect, rather than separate, ideas. In addition, the critic’s key words and neologisms, which he had emphasized in italics, were rendered by Jarry in roman and thus brought into equivalence with the rest of the text. Jarry misattributed the excerpt to his friend, Félix Fénéon, and imposed a new title, “D’Art.” By transforming Dujardin’s words and ideas for his own purposes, Jarry had applied the critic’s theory of art to art criticism.

Excerpt from Edouard Dujardin’s “Le Cloisonisme,” 1888, misattributed to Félix Fénéon, in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

L’Annonciation

Émile Bernard, L’Annonciation, hand-colored zincograph, in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Émile Bernard, L’Annonciation, hand-colored zincograph, in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Perhinderion, no. 2

Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.