The Wild Boy of Laval

If one were to chart the life of Alfred Jarry on a cultural timeline—from his birth in Laval in 1873 to his death in Paris in 1907—it would span the interval between Arthur Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell and Pablo Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon. The midpoint of his brief career coincides with the turn of the twentieth century. A brilliant and creative youth, Jarry moved to Paris in 1891 to prepare for the entrance examination to the elite Ècole normale supérieure. In the interim, he studied philosophy with Henri Bergson and published poetry, prose, and criticism in literary reviews. Jarry’s repeated failure to pass the test soon ceased to matter. By age twenty-one, he was participating in the most important artistic platforms of the era, attracting attention at literary salons including those overseen by the poet Stéphane Mallarmé and the writer Rachilde. The latter’s first impression of Jarry was that he had the look of a wild animal. Many of his contemporaries were struck by his eccentric appearance: black bicycle shorts were virtually his uniform; other clothes were sometimes held together with safety pins and strings; he wore his hair long; and, on rare occasions, he donned women’s shoes. Consistent in all recollections of Jarry is his brutal imagination; he was an exceptional figure whose first books—as Mallarmé wrote—attained, richly, the level of the “Unusual.”

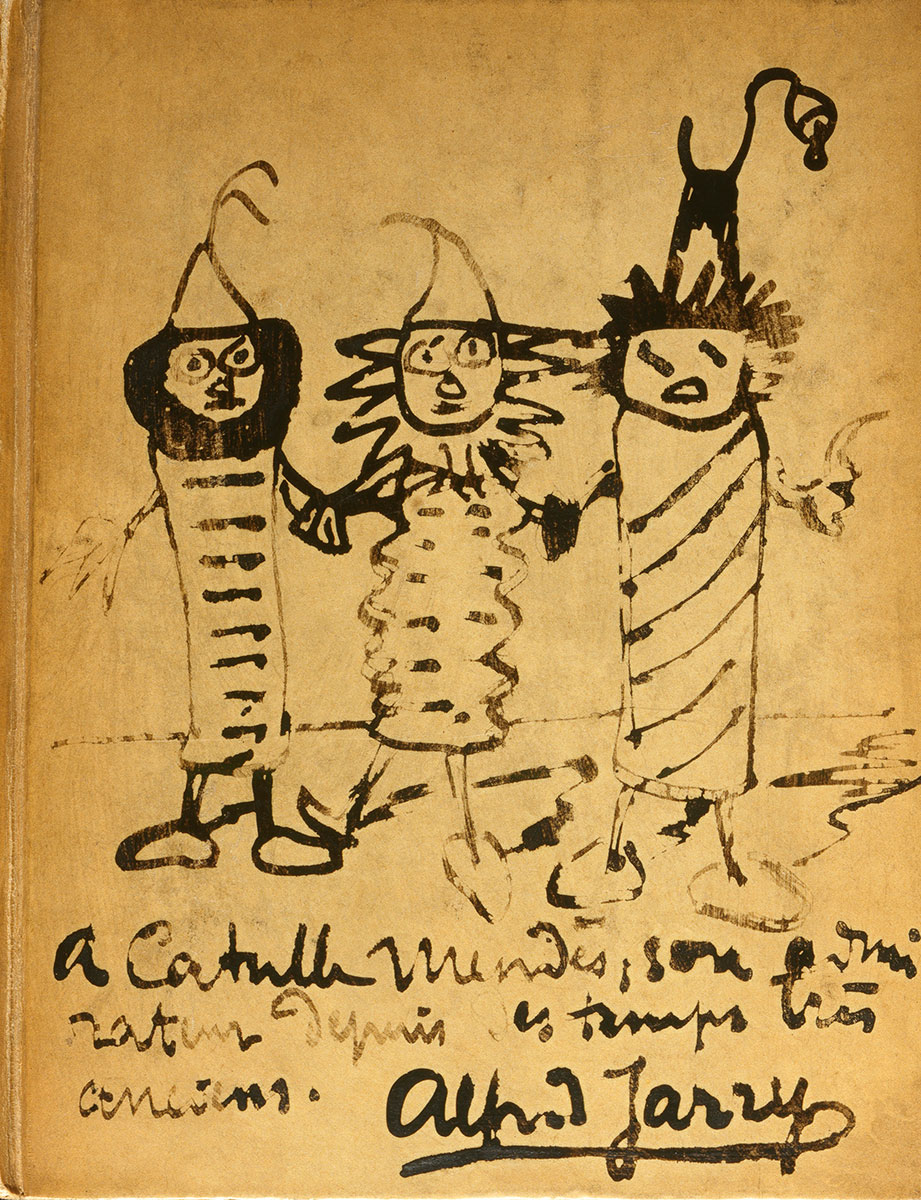

Pen and ink drawing and inscription to Catulle Mendès

As a child, Jarry filled notebooks with humorous sketches, poems, and short plays. The writings he produced by the age of thirteen already include themes of his adult works— scatology, the macabre, a zest for puns, and the scavenging of classical literature—as well as prototypes of later characters and plays. Illustrations figure in many of these early works.

As an adult, he personalized books as gestures of what he called “artistic sympathy.” Jarry drew directly on this plain binding he commissioned and inscribed to Catulle Mendès. In 1893, both Mendès and the writer Marcel Schwob had awarded Jarry a prize for his puppet play titled Guignol. This short work introduced a new character to the literary landscape named Père Ubu, who describes himself as a “great pataphysician.” Mendès’s thoughtful analysis of Ubu roi three years later helped to solidify Jarry’s reputation.

Pen and ink drawing and inscription to Catulle Mendès (1841–1909), ca. 1896. On Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). Collection of Jean Bonna.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Jarry’s exposure to the writings of Marcel Schwob, Stéphane Mallarmé, and the visionary Comte de Lautréamont is evident in his early writing. An assertion Schwob made that “art stands in opposition to general ideas, describes only the individual, desires only the unique. It does not classify; it declassifies” inflected Jarry’s aesthetic in every medium. Other ideas associated with the Symbolist movement figure in the introduction to his first book: he aimed to “suggest” rather than to “define” and to “create in the highway of sentences an intersection of all the words.” Other prefatory remarks were defiantly prophetic: “Every meaning that the reader will find has been foreseen, and he will not find them all.” Scholars have yet to agree on the identity of the spiral-bodied figure in this woodcut.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

A crude draftsman, Jarry developed a personal iconography early in life, using imagery at times like a private language. Owls, spirals, heraldry, and religious or occult symbols recur as motifs in his book illustrations. The chameleons situated above and below the two men in this woodcut evoke a cryptic passage at the end of Haldernablou (1894)—a short play by Jarry about a tragic love affair between a duke and his page. The title is a portmanteau word that integrates the characters’ Breton names (Haldern and Ablou). Both the play, which was originally called Caméléo, and the illustration of the creatures (in French, caméléons) allude to the love affair Jarry had at age eighteen with the younger poet Léon-Paul Fargue. The pair explored Paris and its underworld together while Fargue introduced Jarry to the art scene and literary salons. Their relationship appears to have ended just before the play was published.

A crude draftsman, Jarry developed a personal iconography early in life, using imagery at times like a private language. Owls, spirals, heraldry, and religious or occult symbols recur as motifs in his book illustrations. The chameleons situated above and below the two men in this woodcut evoke a cryptic passage at the end of Haldernablou (1894)—a short play by Jarry about a tragic love affair between a duke and his page. The title is a portmanteau word that integrates the characters’ Breton names (Haldern and Ablou). Both the play, which was originally called Caméléo, and the illustration of the creatures (in French, caméléons) allude to the love affair Jarry had at age eighteen with the younger poet Léon-Paul Fargue. The pair explored Paris and its underworld together while Fargue introduced Jarry to the art scene and literary salons. Their relationship appears to have ended just before the play was published.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Ubu roi

Even before he created the iconic portrait of his character Père Ubu shown here, Jarry was associated with that name. He often signed letters and articles with the moniker and assumed the Ubu persona in public, speaking in a staccato voice devoid of affect. At literary salons, he made a spectacle of himself with spontaneous remarks and recitations related to the Ubu dramas, which dated back to high school marionette plays. Another idiosyncrasy was Jarry’s use of the first-person plural to refer to himself, which he also did when speaking as Ubu; other times, he referred to himself in the third-person singular as Le Père Ubu.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197019.

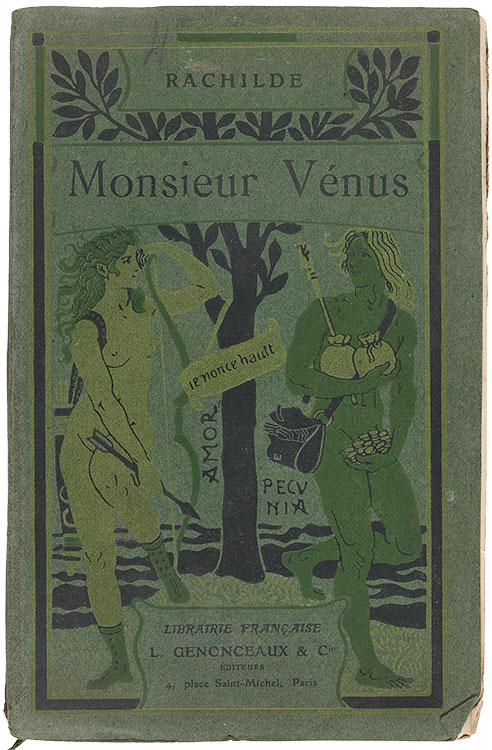

Monsieur Vénus

Jarry often wrote about himself as Père Ubu in letters to the author Rachilde. Born Marguerite Eymery, Rachilde assumed her androgynous pseudonym in the 1880s, regretting, she later wrote, that she had not been born male. Dressing at times in masculine attire, she disparaged female authors and resented being associated with them—her early cartes de visite identify her as an homme de lettres. Rachilde achieved renown for her sexually transgressive novels while Jarry was still in high school. At their first meeting, Jarry told her he was disappointed to discover that the author of Monsieur Vénus was a woman. She would become one of Jarry’s closest friends. Nonconformists in different ways, they shared two essential beliefs— that art is the only ethos, and that the individual is all.

Rachilde (1860–1953), Monsieur Vénus (Paris: Librairie française, L. Genonceaux & cie, 1902). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, Purchased on The Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2019. PML 198187.

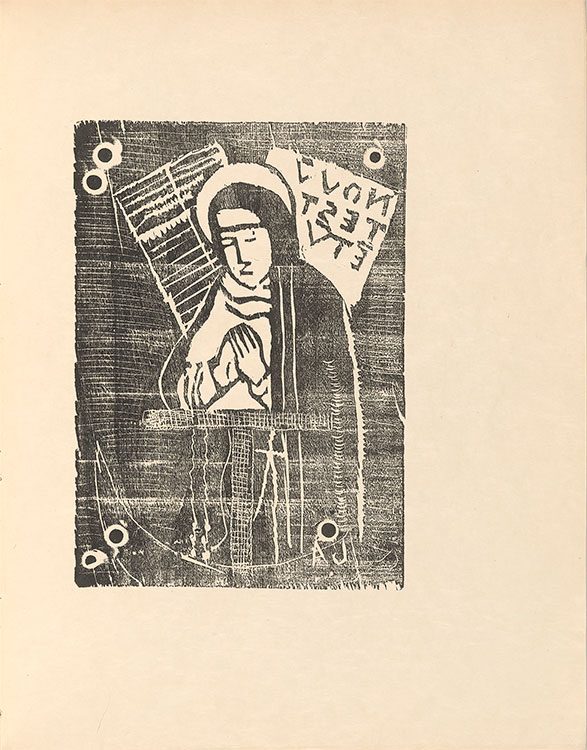

Sainte Gertrude

Jarry’s ideas about book illustration coalesced in 1894—the year he visited the painters’ colony in Pont-Aven, Brittany, then dominated by Paul Gauguin. In a wide-eyed account of this formative experience in a letter to his sister Charlotte, he described how the beautiful landscapes and local “peasant” culture had enabled him to finally understand Impressionist painting. According to Jarry, Gauguin and the artists advised him to stop drinking water and instead drink rum all the time. He found it difficult to keep pace with their carousing given the rough Breton roads and his long rides back to the inn on a bicycle.

Gauguin and the painters Armand Seguin, Charles Filiger, and Roderic O’Conor were also engaged with printmaking. They helped shape the aesthetics of Jarry’s book design by encouraging him, above all, to make his own art, loaning him crude tools to create his first woodcuts.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Sainte Gertrude, woodcut, in L’Ymagier, no. 5 (October 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Three Poems

Jarry derided the use of language to describe visual art, even as an art critic. The exhibition of Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings in Paris in 1893, however, inspired Jarry to write poems about three of the works. Profuse revisions to this draft capture his early attempts to transpose personal impressions of the artist’s exotic, fantastic worlds into subjective visions. Jarry presumably finished the poems in 1894 while spending time with Gauguin in Pont-Aven. They were recorded in a blank book the painter had conceived as “neutral ground” where his friends’ literary and visual art could meet. It was a model Jarry would apply to his own magazine projects, which he initiated later that year.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Autograph manuscript of three poems “after and for” Paul Gauguin, ca. 1893–94. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection as the gift of the Heineman Foundation, 2019. MA 22740.

Le crocodile aux phantasmes

Jarry’s lifelong interest in the macabre figures in one of his few surviving paintings. A melee of grisly creatures and skeletons emerges from the walls and floor of a magician’s study. The appropriation and isolation of existing imagery that would inform Jarry’s book practice is also at play in the painting. It was inspired by a Gustave Doré wood engraving in an old magazine. Jarry’s garishly hued recreation of Doré (known as the “master of black and white”) subverted the defining aesthetic and function of wood engraving, which sought to translate drawings and paintings into grayscale relief.

The crocodile suspended from the top of the necromancer’s study was a popular element in the eighteenth-century cabinets of curiosity that were assembled by wealthy connoisseurs. In 1903, Jarry famously disparaged works of art of his era by comparing them to stuffed crocodiles nailed to the wall—a dead signifier of wealth and banal taste.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Le crocodile aux phantasmes, oil on board, ca. 1894. Collection of Robert Dean. © Jeff McLane Studio, Inc

Les quatre hérauts porte-torches [et] Monsieur Ubu

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les quatre hérauts porte-torches [et] Monsieur Ubu, unknown printing process. Collection of Christophe Champion, Librairie Faustroll.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les quatre hérauts porte-torches [et] Monsieur Ubu, unknown printing process. Collection of Christophe Champion, Librairie Faustroll.