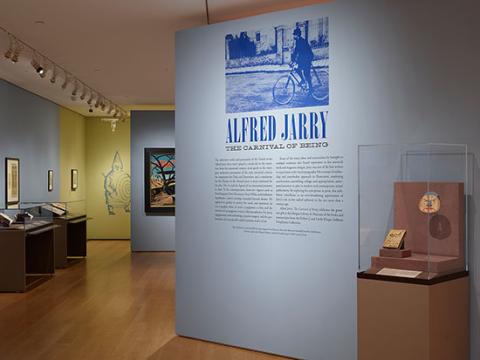

Alfred Jarry: The Carnival of Being

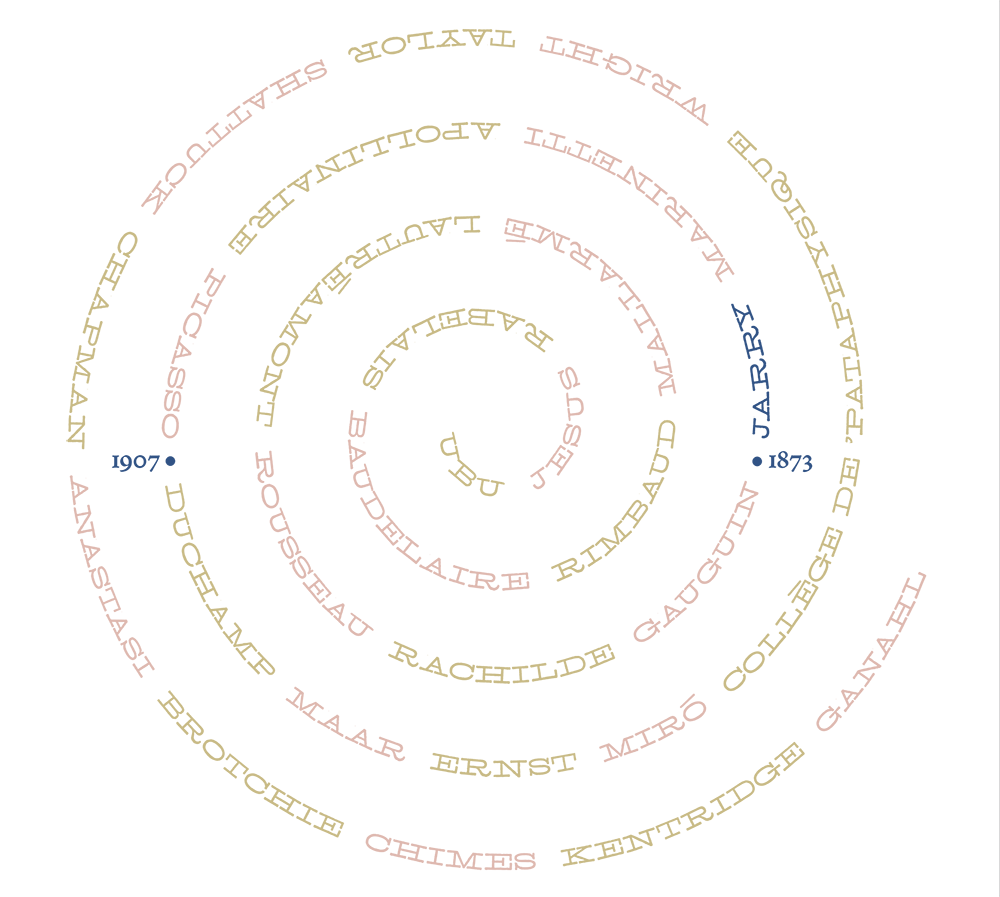

The subversive works and personality of the French writer Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) played a crucial role in the transition from the nineteenth-century avant-garde to the emergent modernist movements of the early twentieth century. An inspiration for Dada and Surrealism and a touchstone for the Theatre of the Absurd, Jarry is most renowned for his play Ubu roi and the legend of its sensational premiere in 1896. To his contemporaries, however—figures such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Rousseau, Oscar Wilde, and Guillaume Apollinaire—Jarry’s prestige extended beyond theater. He applied his genius to poetry, the novel, and operettas; he was a graphic artist, an actor, a puppeteer, a critic, and the inventor of an imaginary science called pataphysics. For Jarry, engagements with technology, popular imagery, and the performance of everyday life could constitute works of art.

Some of the many ideas and innovations he brought to multiple mediums also found expression in his maverick book and magazine designs. Jarry was one of the first writers to experiment with visual typography. His concept of authorship and unorthodox approach to illustration, employing anachronism, assembling, collage, and appropriation, anticipated practices at play in modern and contemporary artists’ publications. By exploring his enterprises in print, this exhibition contributes to an ever-broadening appreciation of Jarry’s role in the radical upheaval in the arts more than a century ago.

To Be and To Live

Jarry’s motto “Living is the carnival of Being” stems from an essay in which he posed the question: Is it better to be or to live? Life, he argued, is tied to duration; it has a beginning and an end, like an action or a word. Being, on the other hand, is consubstantial with eternity and the “iridescent mental kaleidoscope of thinking.” To live out one’s ideas—like the anarchists in the Paris of his youth—is, for Jarry, a fall from grace, for it pulls Being into the void of non-Being. He articulated this in the absurd equation: “To Live = to cease to Exist.” Jarry then resolved this quandary by concluding that: “All murders are beautiful: so let us destroy Being . . . Life and exploits . . . are more beautiful than Thought when, consciously or not, they have killed Thought. Let us then Live, and we shall be the Masters.”

This online exhibition was created in conjunction with the exhibition Alfred Jarry: The Carnival of Being, on view from January 24 through September 13, 2020.

Alfred Jarry: The Carnival of Being celebrates the generous gift to the Morgan Library & Museum of the books and manuscripts from the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection.

This exhibition is made possible by major support from Beatrice Stern, the Sherman Fairchild Fund for Exhibitions, Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, and the Franklin Jasper Walls Lecture Fund.

The Wild Boy of Laval

If one were to chart the life of Alfred Jarry on a cultural timeline—from his birth in Laval in 1873 to his death in Paris in 1907—it would span the interval between Arthur Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell and Pablo Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon. The midpoint of his brief career coincides with the turn of the twentieth century. A brilliant and creative youth, Jarry moved to Paris in 1891 to prepare for the entrance examination to the elite Ècole normale supérieure. In the interim, he studied philosophy with Henri Bergson and published poetry, prose, and criticism in literary reviews. Jarry’s repeated failure to pass the test soon ceased to matter. By age twenty-one, he was participating in the most important artistic platforms of the era, attracting attention at literary salons including those overseen by the poet Stéphane Mallarmé and the writer Rachilde. The latter’s first impression of Jarry was that he had the look of a wild animal. Many of his contemporaries were struck by his eccentric appearance: black bicycle shorts were virtually his uniform; other clothes were sometimes held together with safety pins and strings; he wore his hair long; and, on rare occasions, he donned women’s shoes. Consistent in all recollections of Jarry is his brutal imagination; he was an exceptional figure whose first books—as Mallarmé wrote—attained, richly, the level of the “Unusual.”

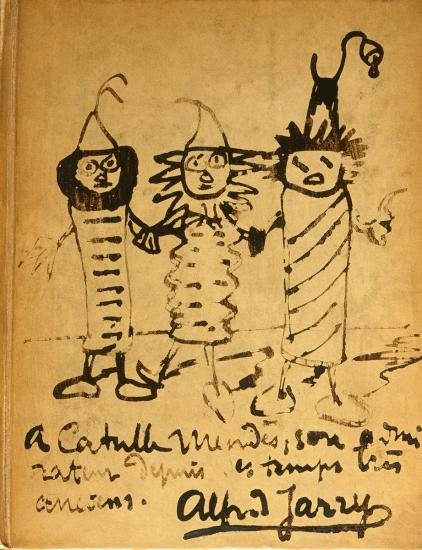

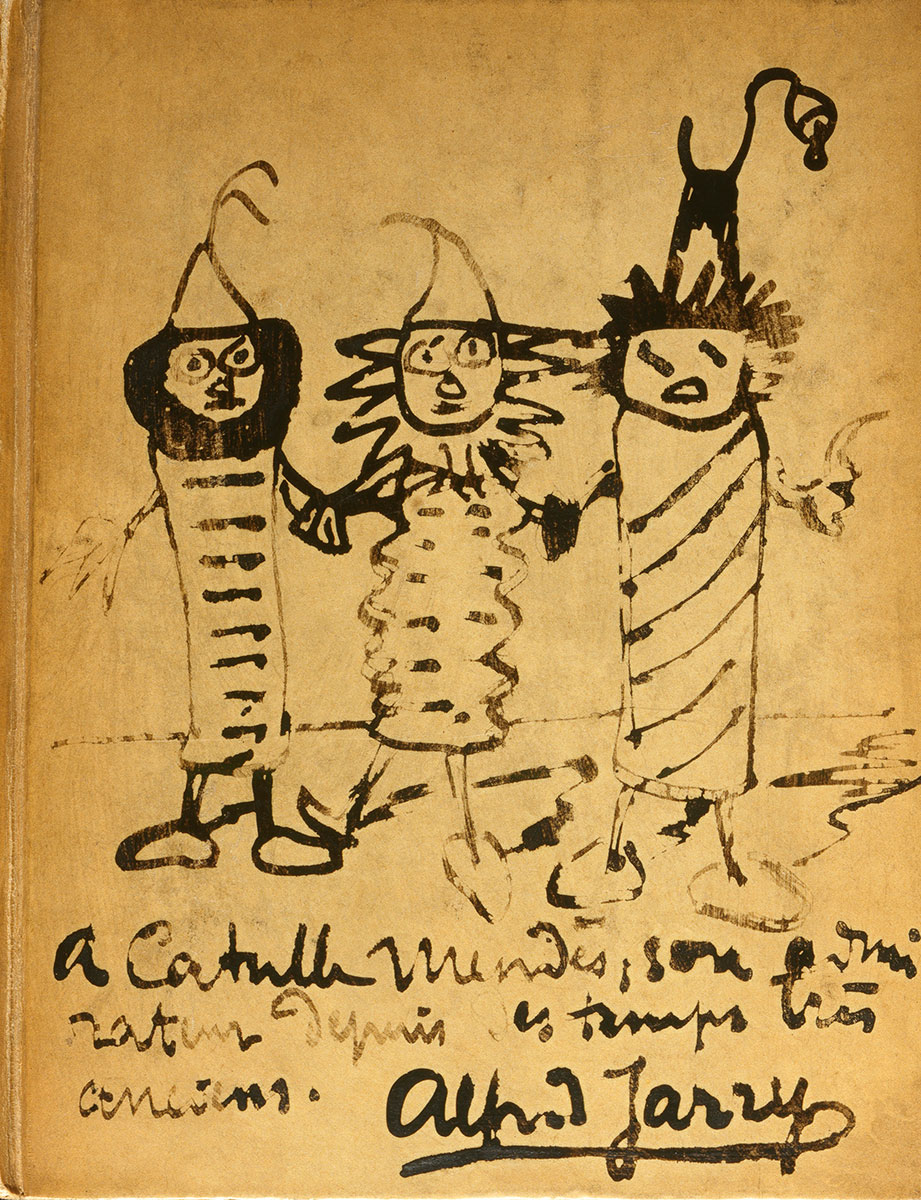

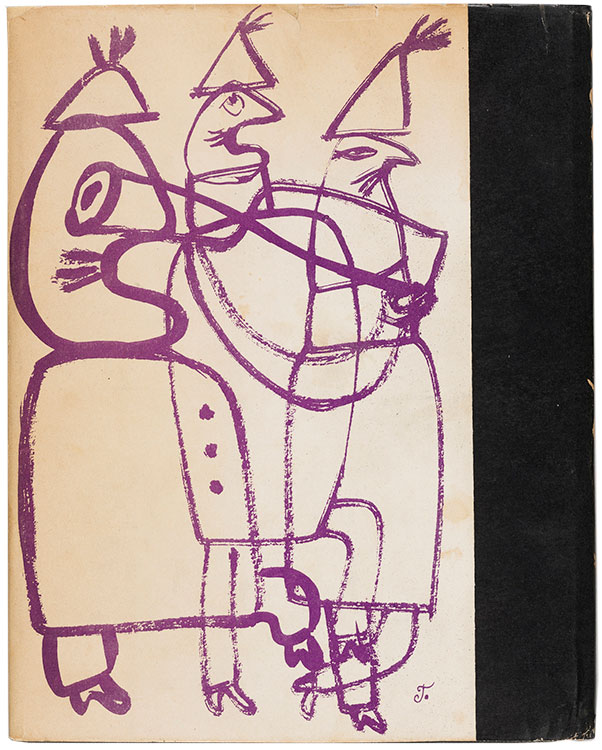

Pen and ink drawing and inscription to Catulle Mendès

As a child, Jarry filled notebooks with humorous sketches, poems, and short plays. The writings he produced by the age of thirteen already include themes of his adult works— scatology, the macabre, a zest for puns, and the scavenging of classical literature—as well as prototypes of later characters and plays. Illustrations figure in many of these early works.

As an adult, he personalized books as gestures of what he called “artistic sympathy.” Jarry drew directly on this plain binding he commissioned and inscribed to Catulle Mendès. In 1893, both Mendès and the writer Marcel Schwob had awarded Jarry a prize for his puppet play titled Guignol. This short work introduced a new character to the literary landscape named Père Ubu, who describes himself as a “great pataphysician.” Mendès’s thoughtful analysis of Ubu roi three years later helped to solidify Jarry’s reputation.

Pen and ink drawing and inscription to Catulle Mendès (1841–1909), ca. 1896. On Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). Collection of Jean Bonna.

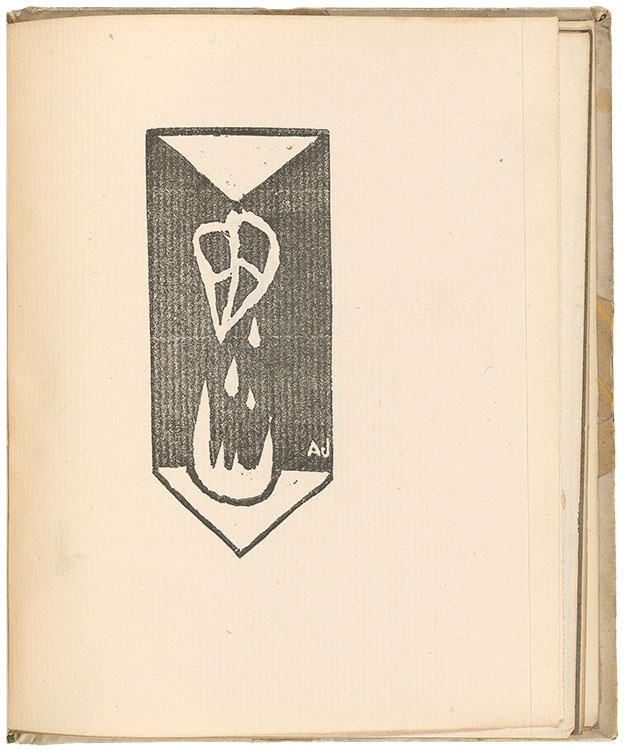

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Jarry’s exposure to the writings of Marcel Schwob, Stéphane Mallarmé, and the visionary Comte de Lautréamont is evident in his early writing. An assertion Schwob made that “art stands in opposition to general ideas, describes only the individual, desires only the unique. It does not classify; it declassifies” inflected Jarry’s aesthetic in every medium. Other ideas associated with the Symbolist movement figure in the introduction to his first book: he aimed to “suggest” rather than to “define” and to “create in the highway of sentences an intersection of all the words.” Other prefatory remarks were defiantly prophetic: “Every meaning that the reader will find has been foreseen, and he will not find them all.” Scholars have yet to agree on the identity of the spiral-bodied figure in this woodcut.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

A crude draftsman, Jarry developed a personal iconography early in life, using imagery at times like a private language. Owls, spirals, heraldry, and religious or occult symbols recur as motifs in his book illustrations. The chameleons situated above and below the two men in this woodcut evoke a cryptic passage at the end of Haldernablou (1894)—a short play by Jarry about a tragic love affair between a duke and his page. The title is a portmanteau word that integrates the characters’ Breton names (Haldern and Ablou). Both the play, which was originally called Caméléo, and the illustration of the creatures (in French, caméléons) allude to the love affair Jarry had at age eighteen with the younger poet Léon-Paul Fargue. The pair explored Paris and its underworld together while Fargue introduced Jarry to the art scene and literary salons. Their relationship appears to have ended just before the play was published.

A crude draftsman, Jarry developed a personal iconography early in life, using imagery at times like a private language. Owls, spirals, heraldry, and religious or occult symbols recur as motifs in his book illustrations. The chameleons situated above and below the two men in this woodcut evoke a cryptic passage at the end of Haldernablou (1894)—a short play by Jarry about a tragic love affair between a duke and his page. The title is a portmanteau word that integrates the characters’ Breton names (Haldern and Ablou). Both the play, which was originally called Caméléo, and the illustration of the creatures (in French, caméléons) allude to the love affair Jarry had at age eighteen with the younger poet Léon-Paul Fargue. The pair explored Paris and its underworld together while Fargue introduced Jarry to the art scene and literary salons. Their relationship appears to have ended just before the play was published.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Ubu roi

Even before he created the iconic portrait of his character Père Ubu shown here, Jarry was associated with that name. He often signed letters and articles with the moniker and assumed the Ubu persona in public, speaking in a staccato voice devoid of affect. At literary salons, he made a spectacle of himself with spontaneous remarks and recitations related to the Ubu dramas, which dated back to high school marionette plays. Another idiosyncrasy was Jarry’s use of the first-person plural to refer to himself, which he also did when speaking as Ubu; other times, he referred to himself in the third-person singular as Le Père Ubu.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197019.

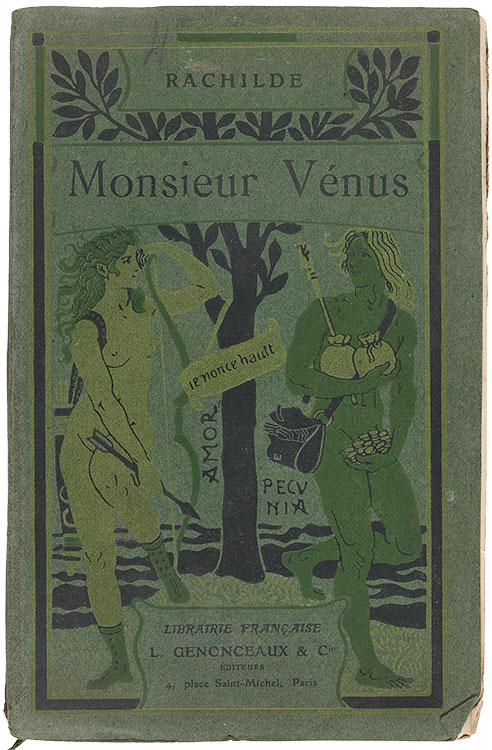

Monsieur Vénus

Jarry often wrote about himself as Père Ubu in letters to the author Rachilde. Born Marguerite Eymery, Rachilde assumed her androgynous pseudonym in the 1880s, regretting, she later wrote, that she had not been born male. Dressing at times in masculine attire, she disparaged female authors and resented being associated with them—her early cartes de visite identify her as an homme de lettres. Rachilde achieved renown for her sexually transgressive novels while Jarry was still in high school. At their first meeting, Jarry told her he was disappointed to discover that the author of Monsieur Vénus was a woman. She would become one of Jarry’s closest friends. Nonconformists in different ways, they shared two essential beliefs— that art is the only ethos, and that the individual is all.

Rachilde (1860–1953), Monsieur Vénus (Paris: Librairie française, L. Genonceaux & cie, 1902). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, Purchased on The Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2019. PML 198187.

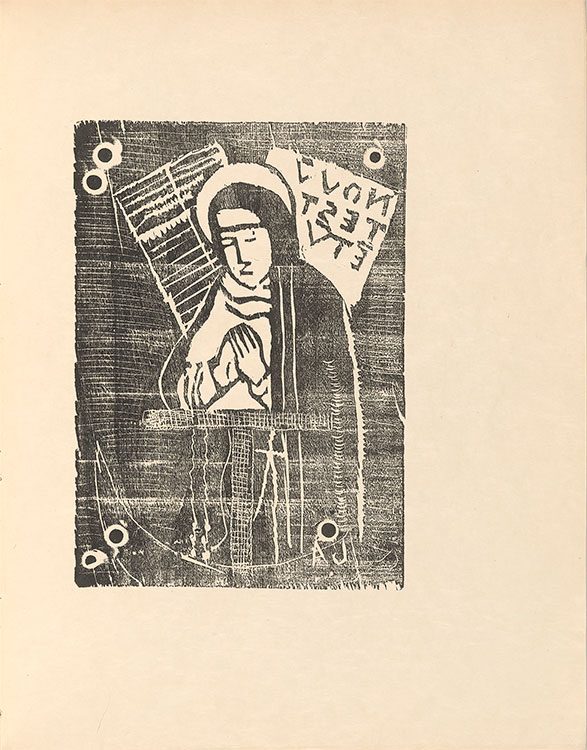

Sainte Gertrude

Jarry’s ideas about book illustration coalesced in 1894—the year he visited the painters’ colony in Pont-Aven, Brittany, then dominated by Paul Gauguin. In a wide-eyed account of this formative experience in a letter to his sister Charlotte, he described how the beautiful landscapes and local “peasant” culture had enabled him to finally understand Impressionist painting. According to Jarry, Gauguin and the artists advised him to stop drinking water and instead drink rum all the time. He found it difficult to keep pace with their carousing given the rough Breton roads and his long rides back to the inn on a bicycle.

Gauguin and the painters Armand Seguin, Charles Filiger, and Roderic O’Conor were also engaged with printmaking. They helped shape the aesthetics of Jarry’s book design by encouraging him, above all, to make his own art, loaning him crude tools to create his first woodcuts.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Sainte Gertrude, woodcut, in L’Ymagier, no. 5 (October 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

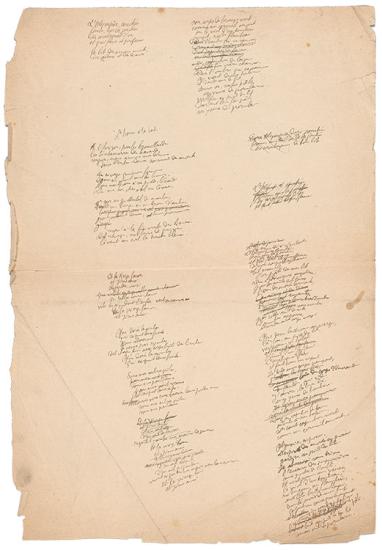

Three Poems

Jarry derided the use of language to describe visual art, even as an art critic. The exhibition of Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings in Paris in 1893, however, inspired Jarry to write poems about three of the works. Profuse revisions to this draft capture his early attempts to transpose personal impressions of the artist’s exotic, fantastic worlds into subjective visions. Jarry presumably finished the poems in 1894 while spending time with Gauguin in Pont-Aven. They were recorded in a blank book the painter had conceived as “neutral ground” where his friends’ literary and visual art could meet. It was a model Jarry would apply to his own magazine projects, which he initiated later that year.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Autograph manuscript of three poems “after and for” Paul Gauguin, ca. 1893–94. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection as the gift of the Heineman Foundation, 2019. MA 22740.

Le crocodile aux phantasmes

Jarry’s lifelong interest in the macabre figures in one of his few surviving paintings. A melee of grisly creatures and skeletons emerges from the walls and floor of a magician’s study. The appropriation and isolation of existing imagery that would inform Jarry’s book practice is also at play in the painting. It was inspired by a Gustave Doré wood engraving in an old magazine. Jarry’s garishly hued recreation of Doré (known as the “master of black and white”) subverted the defining aesthetic and function of wood engraving, which sought to translate drawings and paintings into grayscale relief.

The crocodile suspended from the top of the necromancer’s study was a popular element in the eighteenth-century cabinets of curiosity that were assembled by wealthy connoisseurs. In 1903, Jarry famously disparaged works of art of his era by comparing them to stuffed crocodiles nailed to the wall—a dead signifier of wealth and banal taste.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Le crocodile aux phantasmes, oil on board, ca. 1894. Collection of Robert Dean. © Jeff McLane Studio, Inc

Les quatre hérauts porte-torches [et] Monsieur Ubu

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les quatre hérauts porte-torches [et] Monsieur Ubu, unknown printing process. Collection of Christophe Champion, Librairie Faustroll.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les quatre hérauts porte-torches [et] Monsieur Ubu, unknown printing process. Collection of Christophe Champion, Librairie Faustroll.

The Pataphysics of the Book

Jarry introduced the term “pataphysics” in 1893. He presented it as a given—as if pataphysics was the mother of the invention of pataphysics. Another given, according to Jarry, was that opposites are equivalent. Later, he would write that pataphysics is “the science of imaginary solutions,” concerned with laws that govern exceptions (the particular, rather than the general); it explains the universe supplementary to this one—or, at least, it describes a universe that could and perhaps should be envisioned in place of our own. Unconstrained by time, pataphysics dwells in Eternity and in the imagination of the artist.“God—or myself—created all possible worlds,” wrote Jarry.

The imaginative universe of Jarry’s book and magazine design reflects these pataphysical notions as well as the unfettered nonconformity he brought to bear on all aspects of his life. As proponents of the art of the book attempted to recapture the past, Jarry renovated publishing as an artistic practice. In place of the unity of text, illustration, and type, he welcomed disjointedness and anachronisms, while co-opting existing words and images as his own.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Books figure as hallucinatory or apocalyptic metaphors in Jarry’s writings. He rarely reflected on the subject in essays other than to mock the uniformity of French book covers. Jarry’s first cover designs were chiefly black, with no title or author, just a small heraldic symbol printed in gold. For the special editions, he used medieval imagery from the Ars memorandi (The Art of Memory).

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

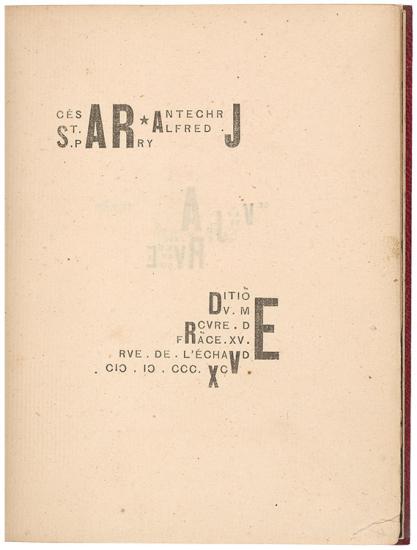

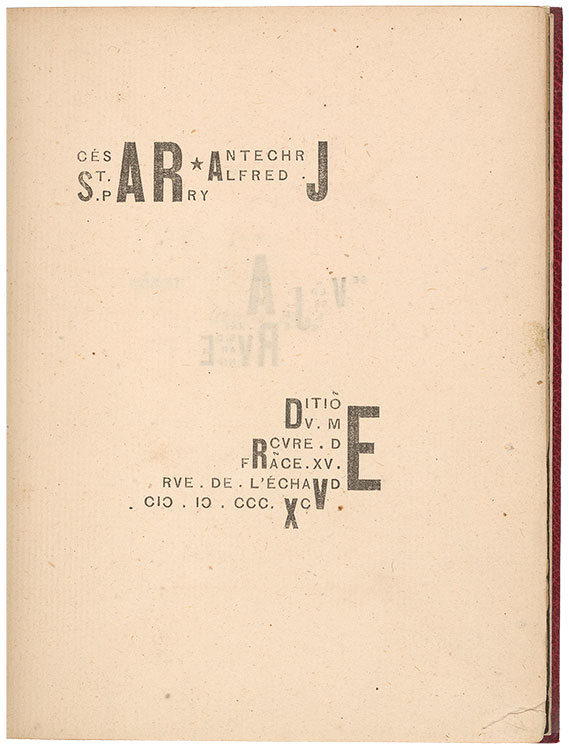

César-antechrist

Now, I had in my hands—since when?—a book—certainly written by me; how and when? no memory— where all that I was to see, all that I was to think afterwards, was foretold. . . . And the letters were pictures.

—Alfred Jarry, “Opium” (1893)

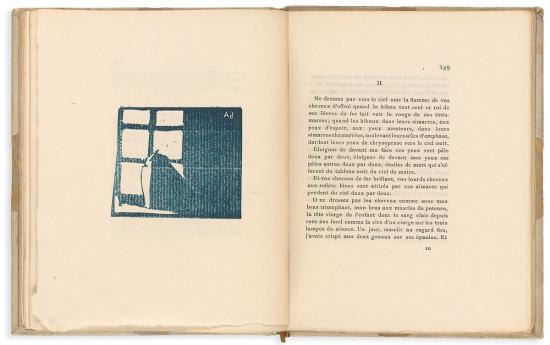

Jarry privileged painting over writing. Images, he argued, can be perceived all at once, whereas writing is sequential and thus constrained by duration. This title-page design defies the linearity of reading, however, presenting itself as both image and information. Some letters operate in multiple words; others are unstable (a J can be an I or a Y). Jarry’s use of medieval tildes (as in Frãce for France) requires the reader to complete the words.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

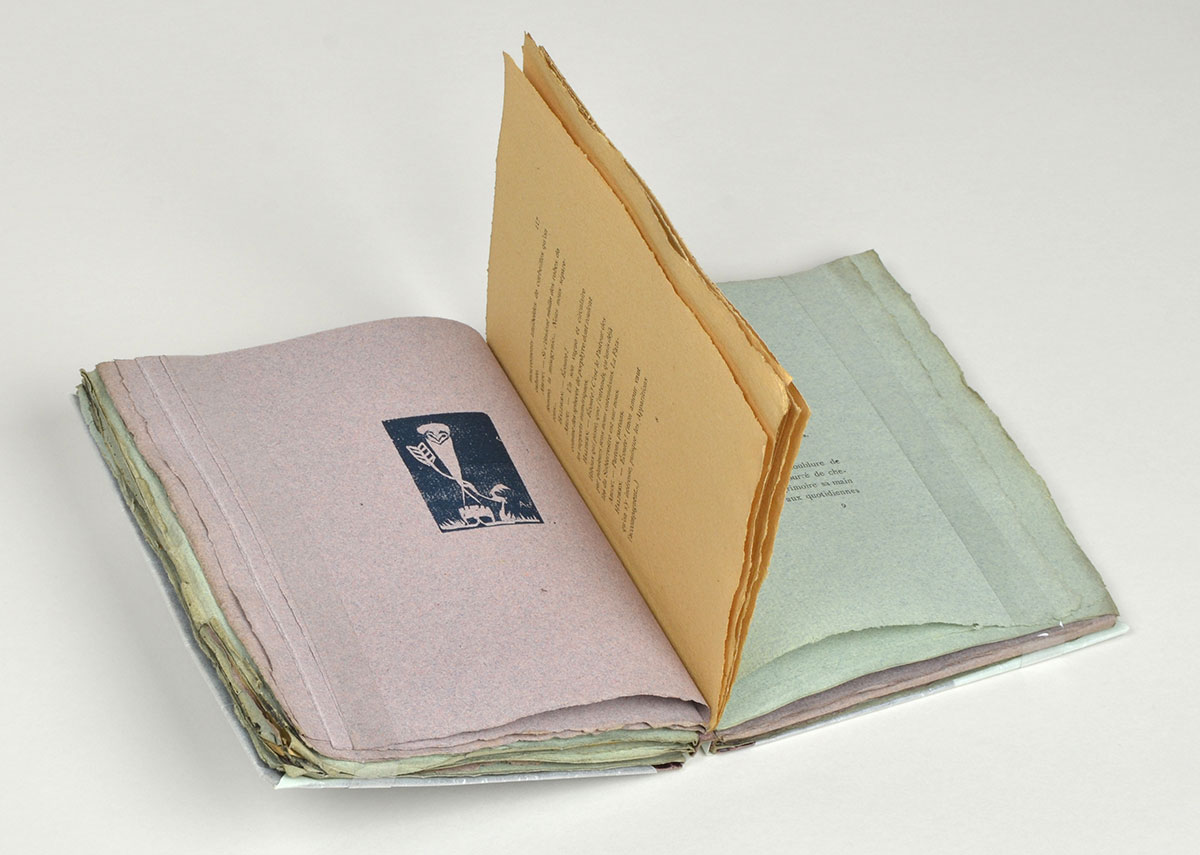

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Jarry’s first publication, Les minutes de sable mémorial, was a collection of poetry, prose, and plays (some were written for puppets). Many pieces by the twenty-one-year-old had appeared previously in avant-garde magazines. His creative approach to the interplay of text and image was unprecedented, however. The Symbolist writer and critic Remy de Gourmont mentored Jarry in the art of the book. As the unofficial artistic director of the magazine Mercure de France and its imprint, Gourmont had established a house style that was both modern and medieval, informed by advertising and the aesthetics of early printing. Jarry absorbed his mentor’s taste and used it as a point of departure for his experimental designs, going so far on two occasions as to produce a book on three different-colored papers.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). Collection of Christophe Champion, Librairie Faustroll.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

The woodcut illustrations Jarry began to create in 1894 around the artists at Pont-Aven combined a crude modern aesthetic with primitive imagery he came across in old religious prints. Unlike his contemporaries, he made no attempt to unify the disparate designs within his early books. Claustrophobic arrangements of ornaments, obscure forms, occult symbols and other designs that verge on abstraction were melded into one visual vocabulary.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017

César-antechrist

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

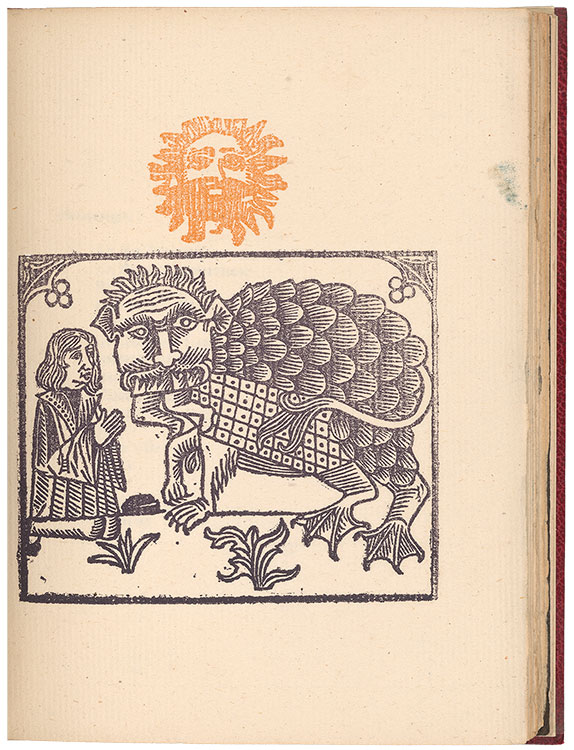

César-antechrist

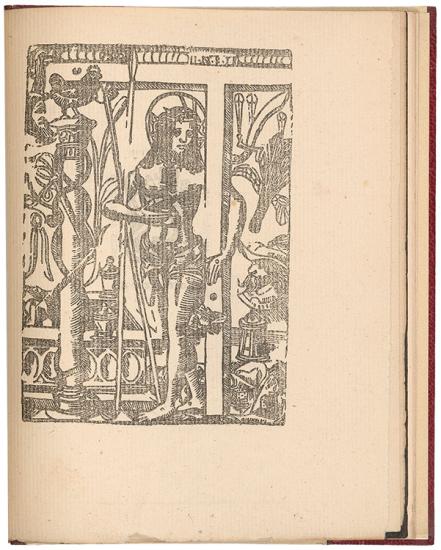

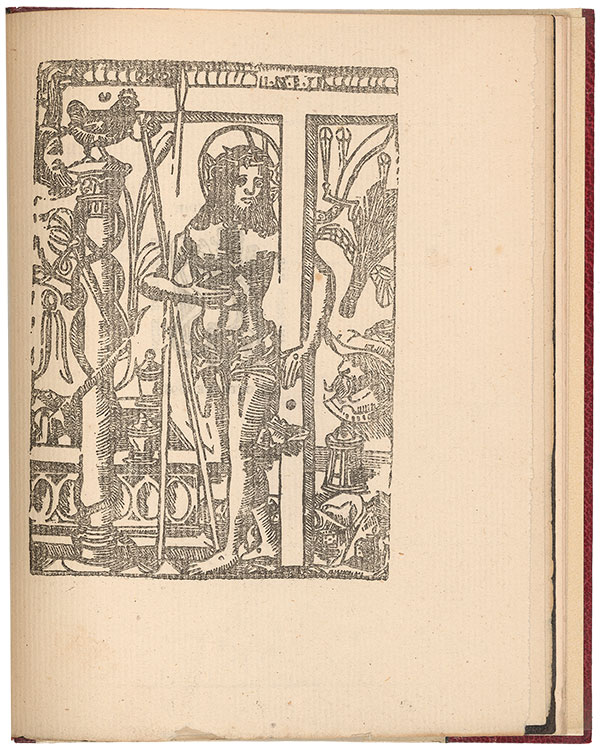

In his early books, Jarry interspersed his own woodcuts (or line drawings he passed off as woodcuts) with found imagery. This illustration for his second book is a composite design of two Renaissance woodcuts. He appropriated most of these kinds of woodcuts from an old catalogue documenting four centuries of popular imagery. Their unacknowledged presence in tandem with Jarry’s modern literature and design seemed to resituate the past in the contemporary or, conversely, suggested that Jarry’s work is itself anachronous. His engagement with both the Middle Ages and the modern shares traits with Baudelaire’s definition of beauty and ideas suggested by Nietzsche’s Meditations on the Untimely; but Jarry fractured this unity in the realm of the book arts. Such disharmony was at odds with figures such as William Morris who were attempting to unify book design in ways that reflected Richard Wagner’s concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

Les minutes de sable mémorial

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Les minutes de sable mémorial (Paris: Mercure de France, 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197017.

César-antechrist

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

César-antechrist

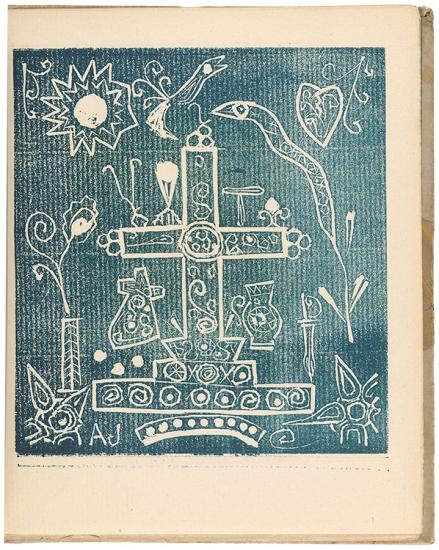

The privileging of found imagery over original designs became more pronounced in Jarry’s second book. This frontispiece, which is one of only two original illustrations in his apocalyptic drama César-antechrist, is something of a hybrid. Jarry chose elements from multiple woodcut illustrations in a popular renaissance series of papal prophecies; he rearranged them and added hand-drawn elements to his busy design. By merging a catalogue of images into one pictorial field, Jarry’s collage suggests a Cubist approach to “reading” an illustrated book on one page.

The privileging of found imagery over original designs became more pronounced in Jarry’s second book. This frontispiece, which is one of only two original illustrations in his apocalyptic drama César-antechrist, is something of a hybrid. Jarry chose elements from multiple woodcut illustrations in a popular renaissance series of papal prophecies; he rearranged them and added hand-drawn elements to his busy design. By merging a catalogue of images into one pictorial field, Jarry’s collage suggests a Cubist approach to “reading” an illustrated book on one page.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist (Paris: Mercure de France, 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197018.

Source imagery, Prophetia dello abbate Joachino circa li Pontifici [et] R.E. (Venice: Niccolò & Domenico dal Gesù, 1527),The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased in 1925. PML 23177.

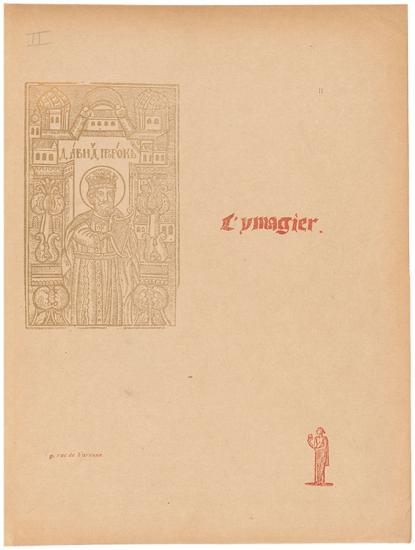

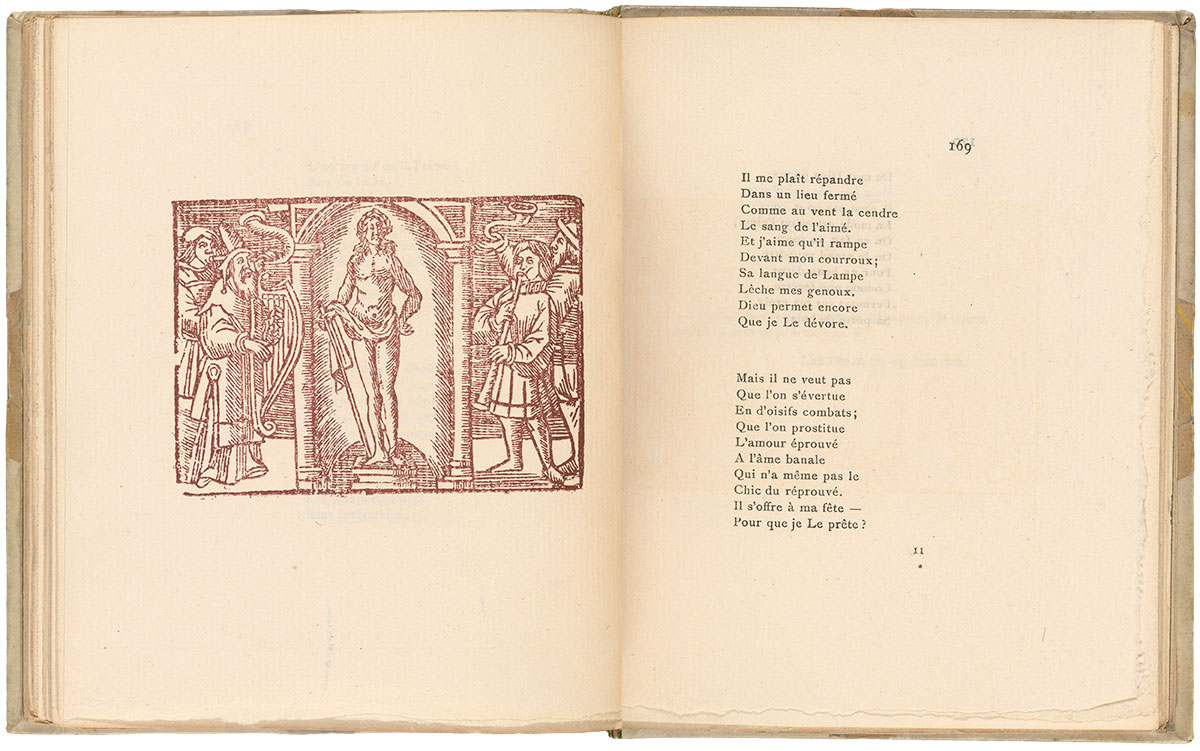

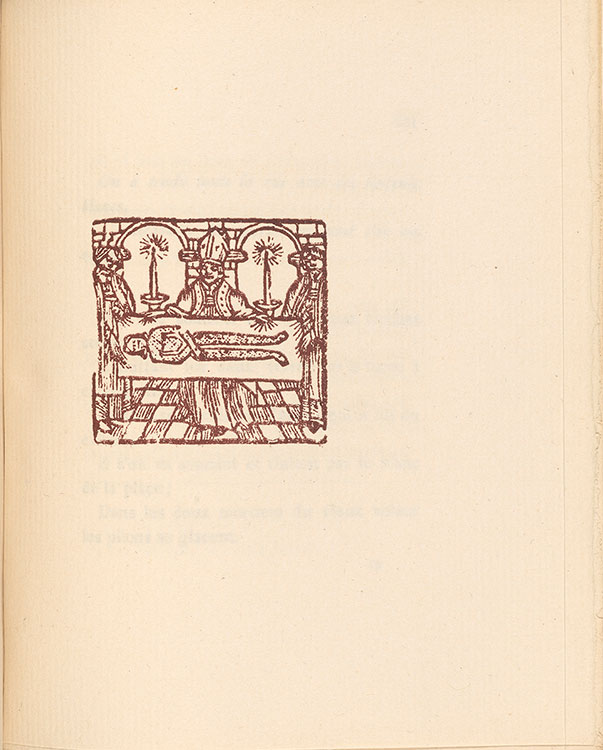

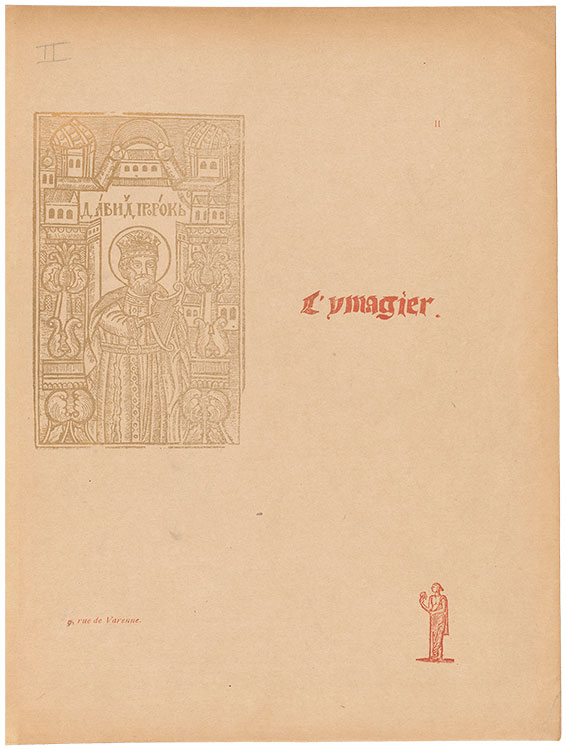

L’Ymagier

Jarry’s first magazine, L’Ymagier (1894-96), which he coedited with Remy de Gourmont, reversed the traditional separation of disparate forms, genres, and artistic periods. As a kind of radical museum in print, the magazine not only proposed equivalence across modern history and high and low culture but also questioned the distinction between original and copy. Gourmont and Jarry each contributed a few prints of their own usually under pseudonyms. Most of their contributions, however, were essays and commentaries on visual iconography over time. The chimerical, time-bending aesthetic of the magazine conformed to Jarry’s inverted definition of beauty in the second issue, which defined the monstrous as “all original, inexhaustible beauty.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Remy de Gourmont (1858–1915), eds., L’Ymagier no. 2 (1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

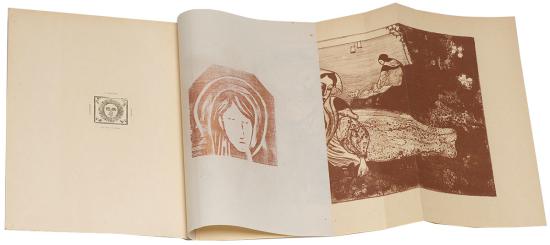

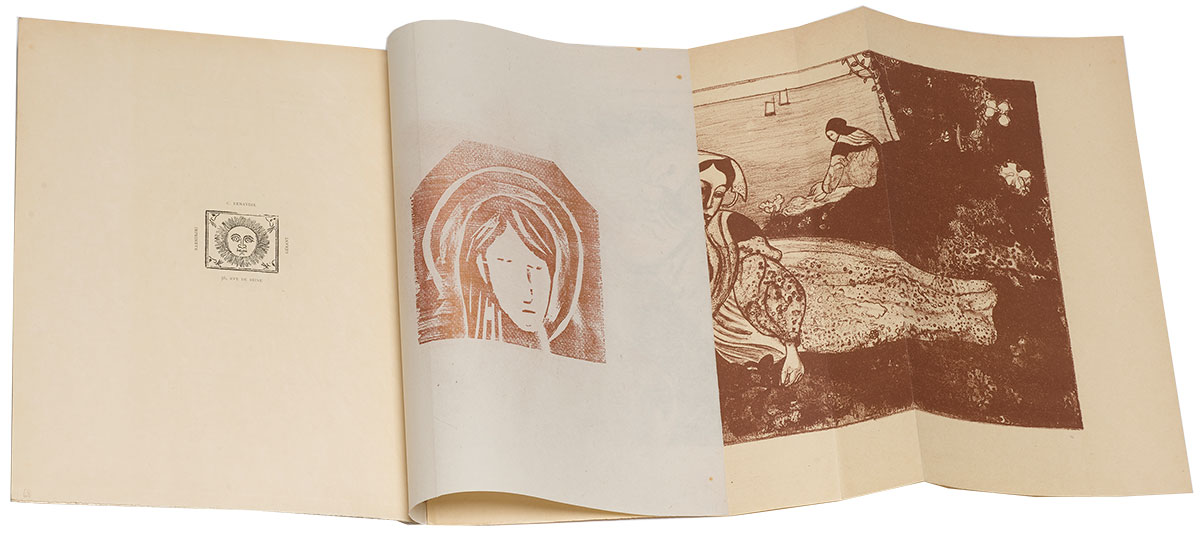

Sainte Madeleine

Many of the prints in L’Ymagier were reproduced on sliver-thin exotic or colored papers that, when folded, might open vertically, horizontally, or both. Contemporary prints by several of the artists he knew in Pont-Aven—including Charles Filiger, Paul Gauguin, Armand Séguin, and Roderic O’Conor—and other painters he admired, such as Émile Bernard and Henri Rousseau, were collated with Renaissance and folkloric imagery, Épinal prints, facsimiles of early typography, and non-Western art.

Found imagery, Remy de Gourmont (1858–1915), Sainte Madeleine, wood engraving, and Armand Séguin (1869–1903), Femme couchée, zincograph, in L’Ymagier, no. 2 (January 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

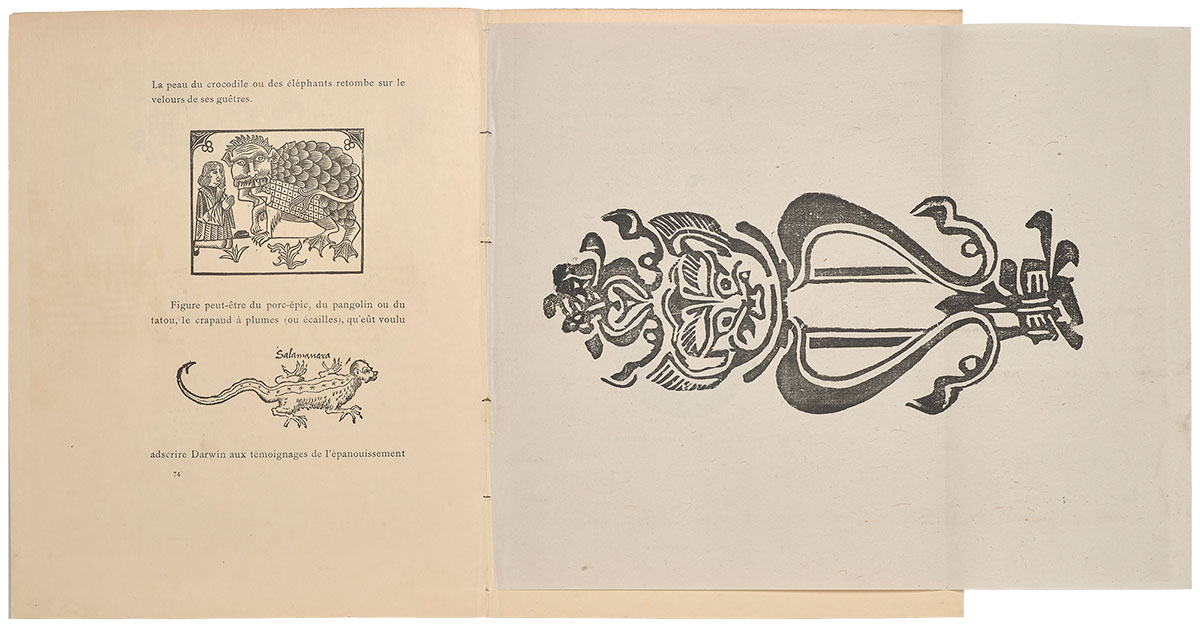

“Les Monstres”

Found imagery and Southeast Asian woodcut, in Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), “Les Monstres,” in L’Ymagier no. 2 (January 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

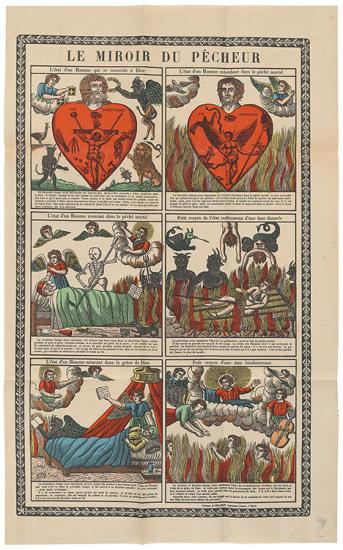

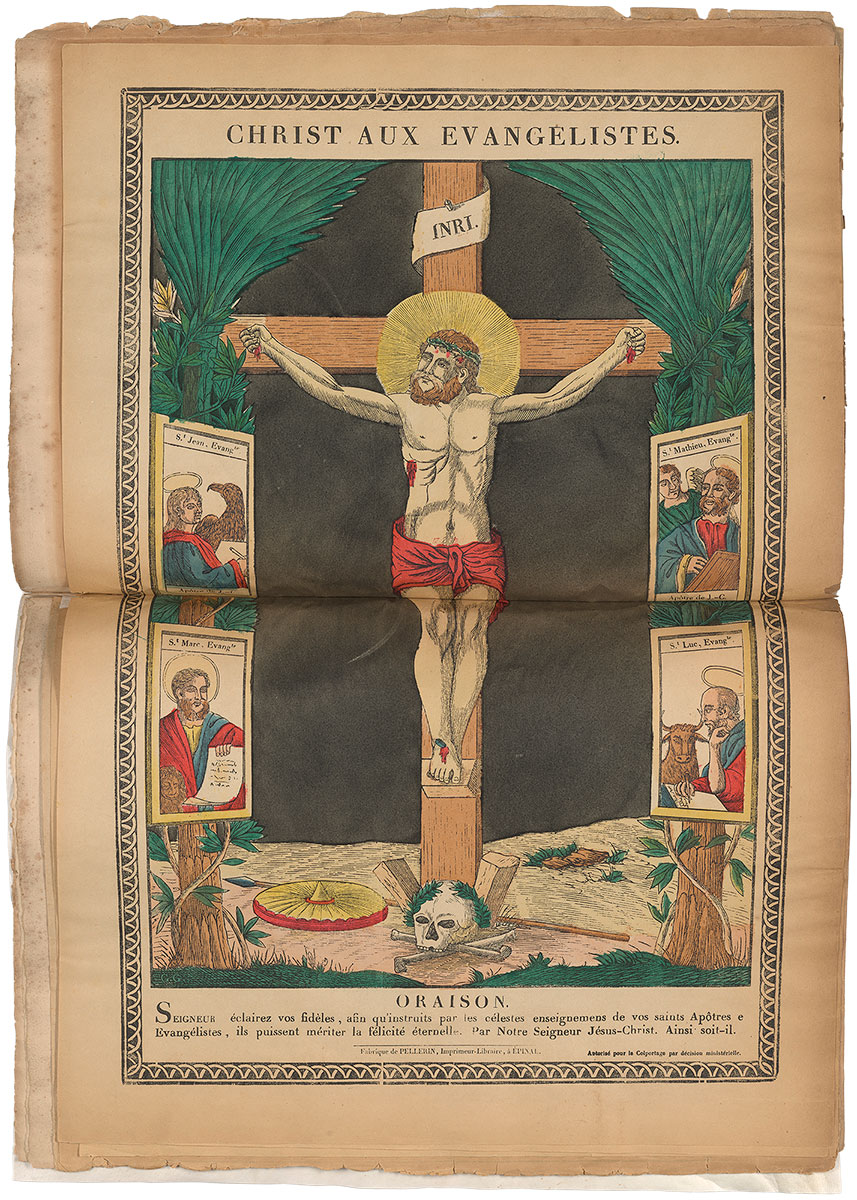

Jésus sur la croix

Large Épinal prints were folded and bound directly into the magazine. These cheap color-stenciled woodcuts were still available in bookstalls along the Seine, but their primitive quality belonged to an earlier part of the nineteenth century. By the 1890s, the Pellerin firm was reproducing the woodcuts using photomechanical processes. Jarry and Gourmont commissioned hundreds of copies to include in L’Ymagier. In essays relating to the iconography and history of the woodcut, the editors lauded the most famous engraver of Épinal prints, François Georgin, as a master worthy of comparison to Albrecht Dürer.

François Georgin (1801–1863), Jésus sur la croix, Épinal print, 1824, reprinted by the Pellerin firm, in L’Ymagier, no. 1 (October 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. And Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Notre-Dame des Ermites

François Georgin (1801–1863), Notre-Dame des Ermites, Épinal print, 1824, reprinted by the Pellerin firm, in L’Ymagier, no. 3 (April 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. And Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Le Miroir du pécheur

François Georgin (1801–1863), Le Miroir du pécheur, Épinal print, 1825, reprinted by the Pellerin firm, in L’Ymagier, no. 1 (October 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. And Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

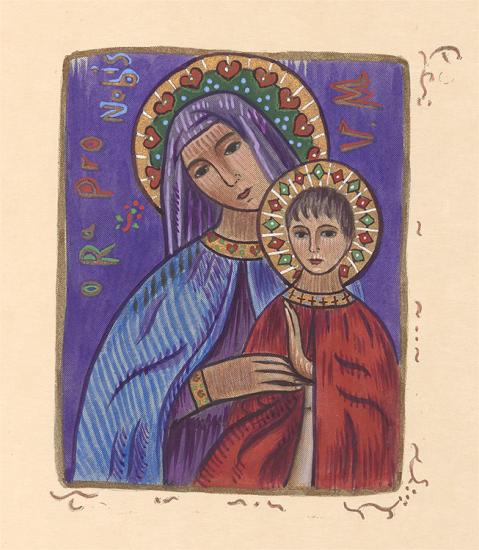

Vierge à l’enfant

Charles Filiger (1863–1928), Vierge à l’enfant (also known as Ora pro nobis), photomechanical print with added hand stenciling, in L’Ymagier, no. 1 (October 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

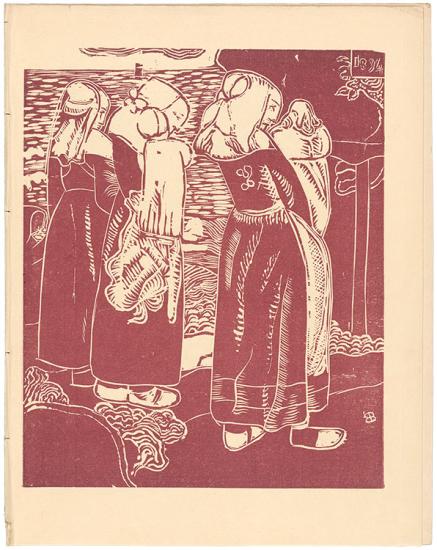

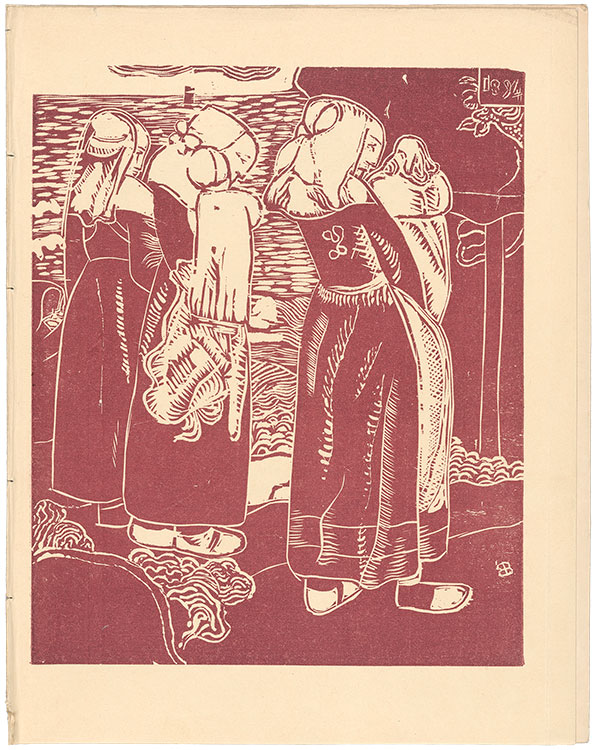

Bretonnes

Armand Séguin (1869–1903), Bretonnes, reproduction of a woodcut, in L’Ymagier, no. 2 (January 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

L’Ymagier, no. 1

L’Ymagier, no. 1 (October 1894). The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Monstrorum historia

Reproduction of a woodcut from Ulisse Aldrovandi, Monstrorum historia (Bologna: Nicolai Tebaldini, 1642), in L’Ymagier, no. 5 (October 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197082.

César-antechrist in L’Ymagier

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), César-antechrist, lithograph, in L’Ymagier, no. 2 (January 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

Henri Rousseau

Of H. Rousseau: there is above all “War (terrifying, she passes . . . ).” With legs outstretched the horror- struck steed stretches its neck with its dancer’s head, black leaves inhabit the mauve clouds, and bits of debris fall like pine cones among the translucent corpses of axolotls attacked by bright-beaked crows.

—Alfred Jarry, “Minutes d’art,” 1894

In his singular, independent approach to life and art, Henri Rousseau, much like Jarry, was viewed as sui generis. The painter was also a native of Jarry’s hometown, Laval. They were nearly thirty years apart in age and did not meet until 1894 in Paris. Few artifacts survive attesting to their friendship, although they lived together briefly.

Rousseau’s painting La guerre was the subject of ridicule when it was exhibited in 1894 at the Salon des Indépendants, but it made a significant impact on the twenty-year-old Jarry and inaugurated their friendship. Jarry wrote about the work in two separate articles and also commissioned Rousseau to create a lithograph based on the painting. Jarry’s immediate recognition of Rousseau’s talent and their compatibility became the stuff of legend: Guillaume Apollinaire and others spread apocryphal stories that Jarry “discovered” Rousseau and assigned him the nickname “Le Douanier” (the customs officer).

Henri Rousseau (1844–1910), La guerre, ca. 1894, oil on canvas. Paris, musée d’Orsay. © RMN-Grand Palais / Erich Lessing/ Art Resource, N.Y.

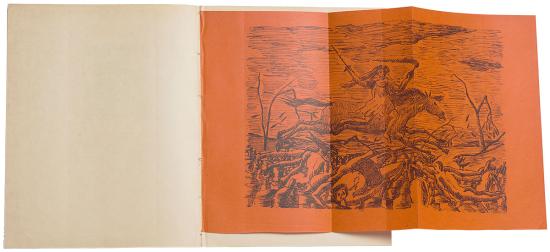

La guerre in L’Ymagier

Rousseau’s only lithograph was the one he created after his painting La guerre expressly for L’Ymagier. He made significant changes to the figures and the landscape, suggestive of the naive popular imagery the magazine often featured. Rousseau also painted a portrait of Jarry (now lost) that was listed in the catalogue for the Salon des Indépendants in 1895 as Portrait de Madame A.J.

Rousseau’s only lithograph was the one he created after his painting La guerre expressly for L’Ymagier. He made significant changes to the figures and the landscape, suggestive of the naive popular imagery the magazine often featured. Rousseau also painted a portrait of Jarry (now lost) that was listed in the catalogue for the Salon des Indépendants in 1895 as Portrait de Madame A.J.

Henri Rousseau (1844–1910), La guerre, lithograph, in L’Ymagier, no. 2 (January 1895). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197080.

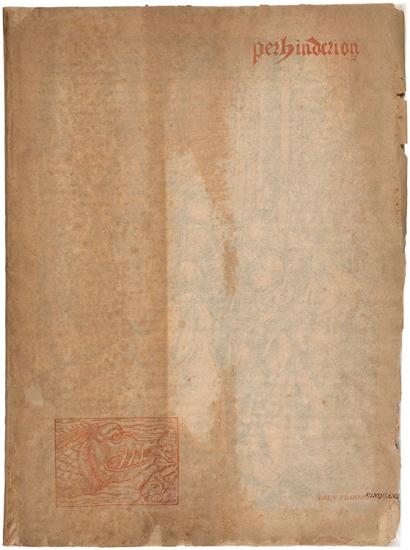

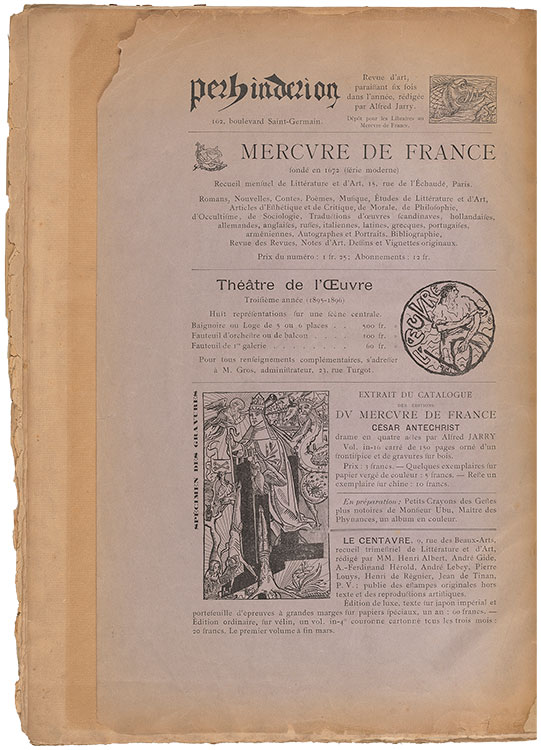

Perhinderion

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), ed., Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

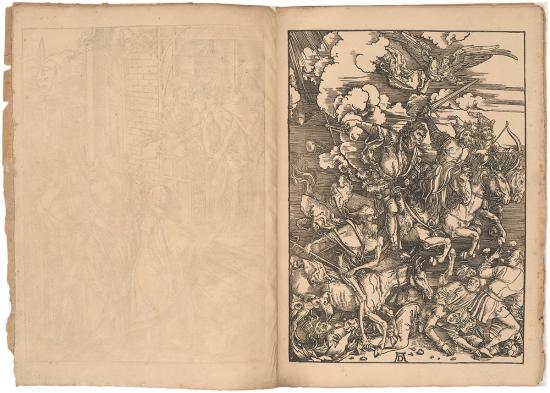

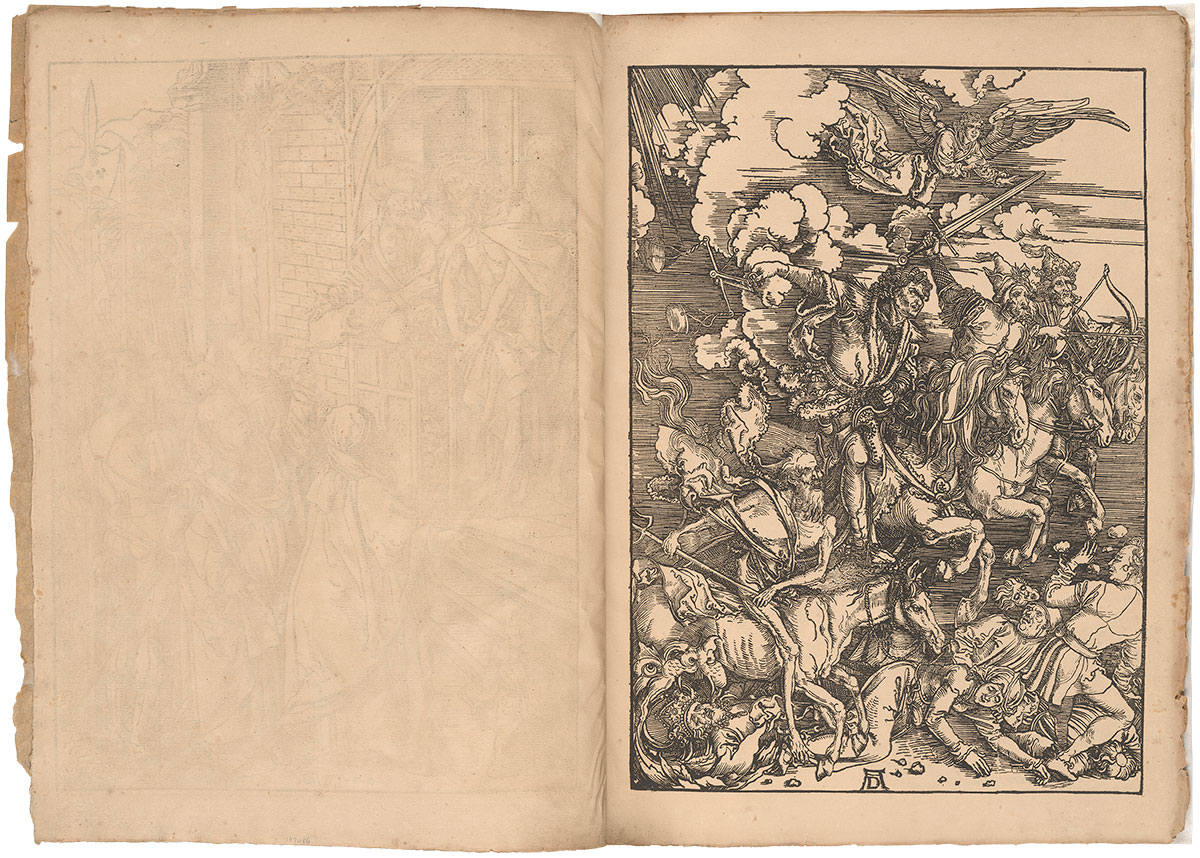

The Four Horsemen

Jarry’s collaborations and friendship with Remy de Gourmont ended due to a prank Jarry and his friends played on his mentor’s mistress. After five issues of L’Ymagier (which was largely bankrolled by the mistress), he started his own magazine: Perhinderion. The title is a Breton word for “pilgrimages.” In his editorial statement, Jarry compared himself to the simple men who peddled religious keepsakes to the devout masses. Jarry was much more ambitious, however. It was his intention to publish Albrecht Dürer’s complete works in the magazine over time. The expense of the luxurious venture exhausted his finances after two issues.

Jarry’s collaborations and friendship with Remy de Gourmont ended due to a prank Jarry and his friends played on his mentor’s mistress. After five issues of L’Ymagier (which was largely bankrolled by the mistress), he started his own magazine: Perhinderion. The title is a Breton word for “pilgrimages.” In his editorial statement, Jarry compared himself to the simple men who peddled religious keepsakes to the devout masses. Jarry was much more ambitious, however. It was his intention to publish Albrecht Dürer’s complete works in the magazine over time. The expense of the luxurious venture exhausted his finances after two issues.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Four Horsemen, from The Apocalypse, 1498, in Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

Christ aux Evangelistes

François Georgin (1801–1863), Christ aux Evangelistes, Épinal print, ca. 1827, in Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

Passage du Mont Saint-Bernard

François Georgin (1801–1863), Passage du Mont Saint-Bernard, Épinal print, ca. 1831, in Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

François Georgin (1801–1863), Passage du Mont Saint-Bernard, Épinal print, ca. 1831, in Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

Le Juif-errant

François Georgin (1801–1863), Le Juif-errant, Épinal print, ca. 1826, in Perhinderion no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

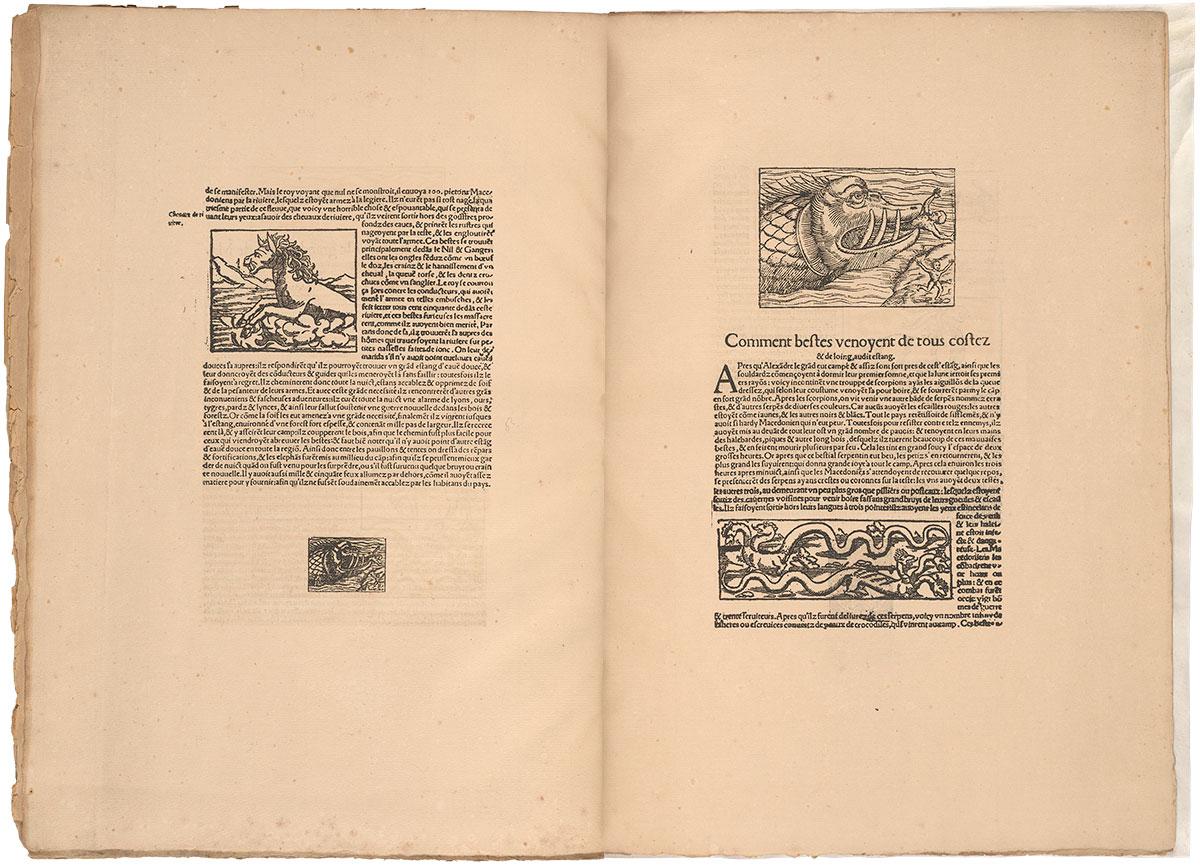

La cosmographie universelle

By 1896, Jarry had been experimenting for two years with composite illustrations and with the integration of found imagery and original woodcuts. He had sometimes passed off his own primitive drawings and prints as woodcuts; he had recycled imagery in multiple publications and pursued his interest in early typography; and he had used the practice of assembling texts and images to create new conceptions of printed matter. These early investigations persisted in Perhinderion using almost no original content of his own. Jarry’s creative gestures registered indirectly, however. This spread appears to be a facsimile. It is actually a collage of multiple pages Jarry chose from a sixteenth-century book.

Composite page designs based on Sebastian Münster’s La cosmographie universelle (1552), in Perhinderion, no. 1 (March 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

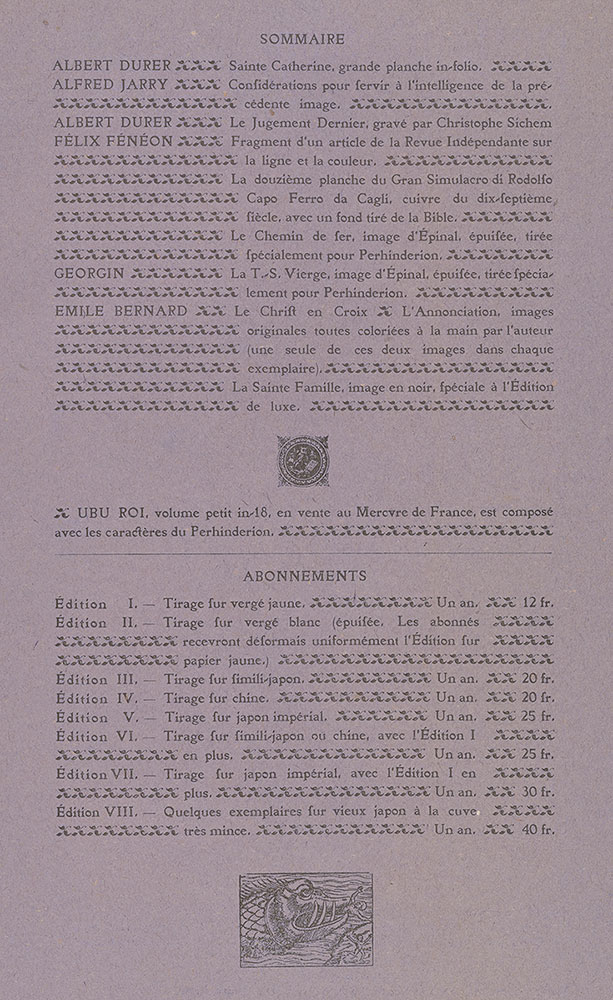

Perhinderion, no. 1

Perhinderion, no. 1 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197086.

Perhinderion, no. 2

Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

The Martyrdom of St. Catherine of Alexandria

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), The Martyrdom of St. Catherine of Alexandria, n.d., in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

“Considérations pour server à l’intelligence de la précédente image”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), “Considérations pour server à l’intelligence de la précédente image,” in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

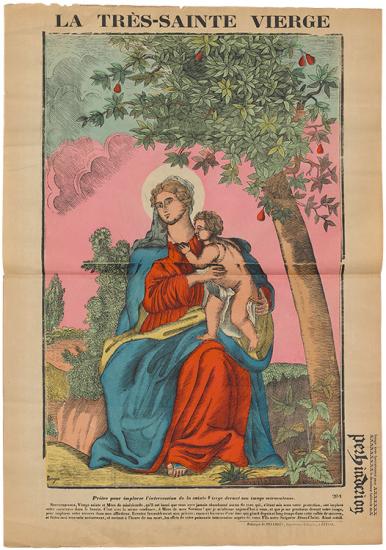

La très sainte Vierge

François Georgin (1801–1863), La très sainte Vierge, Épinal print, 1837, in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

Le chemin de fer

Unidentified artist, Le chemin de fer, Épinal print, 1838, in Perhinderion no. 2 (June 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

Unidentified artist, Le chemin de fer, Épinal print, 1838, in Perhinderion no. 2 (June 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

D’Art

This page contains an extract from Édouard Dujardin’s influential essay from 1888, titled “Cloisonnism.” Jarry chose the passage in which Dujardin argued that the source of an artist’s imagery, be it a Japanese or Épinal print, is insignificant in comparison to the purpose the image serves for an artist’s project. Jarry set the text in the Renaissance-style type he had acquired and named for Perhinderion. The antiquated letterforms and punctuation include the long s, which resembles f, and ligatures; Jarry replaced Dujardin’s semicolons with colons, as if to connect, rather than separate, ideas. In addition, the critic’s key words and neologisms, which he had emphasized in italics, were rendered by Jarry in roman and thus brought into equivalence with the rest of the text. Jarry misattributed the excerpt to his friend, Félix Fénéon, and imposed a new title, “D’Art.” By transforming Dujardin’s words and ideas for his own purposes, Jarry had applied the critic’s theory of art to art criticism.

Excerpt from Edouard Dujardin’s “Le Cloisonisme,” 1888, misattributed to Félix Fénéon, in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

L’Annonciation

Émile Bernard, L’Annonciation, hand-colored zincograph, in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Émile Bernard, L’Annonciation, hand-colored zincograph, in Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Perhinderion, no. 2

Perhinderion, no. 2 (1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197087.

The Author of Ubu Roi

Jarry’s reputation as a genius provocateur solidified at the premiere of his play Ubu roi. The violent satire stemmed from puppet shows that were collaborations between Jarry, his sister, and two classmates in high school. Ubu, a grotesque buffoon inspired by their physics teacher, remained the vehicle for Jarry’s creative projects for the rest of his life.

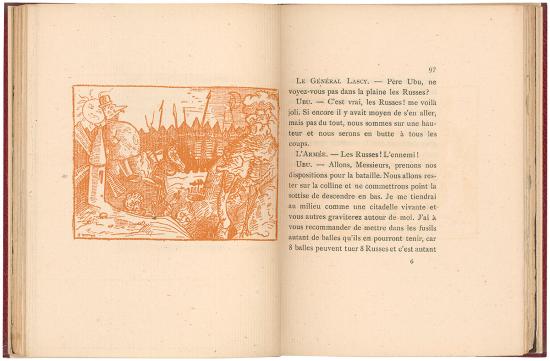

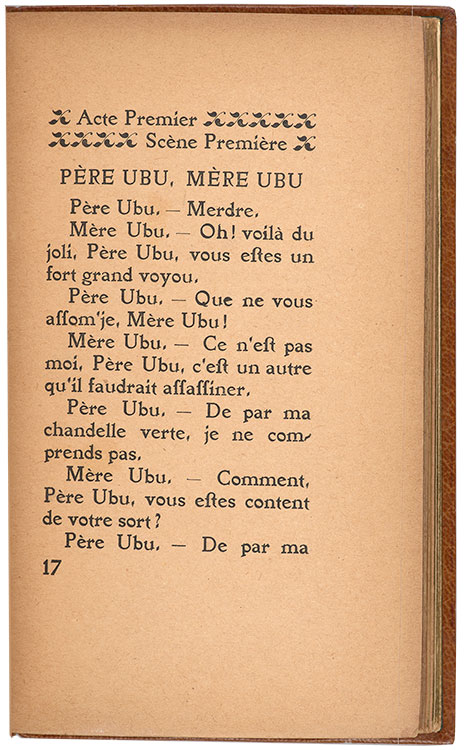

The plot was simple: A tyrant usurps the Polish throne. He slaughters his enemies, meets defeat at the hands of the Russians, and escapes on a vessel headed toward France. The first word uttered on stage was Ubu’s yawp: “Merdre.” Jarry’s neologism added a second r to merde, the French word for “shit.” Wearing a cardboard mask, Ubu appeared barely human and spoke in an unmodulated voice. His feral physicality unsettled the crowd, as did the scenery (every setting was combined on one painted backdrop). As a whole, Ubu roi seemed to signify the imposition of artistic will on established modes of making art, heightened by its absurdities and the author’s apparent indifference to the audience’s comprehension. The play’s public dress rehearsal and single performance reverberated for years to come.

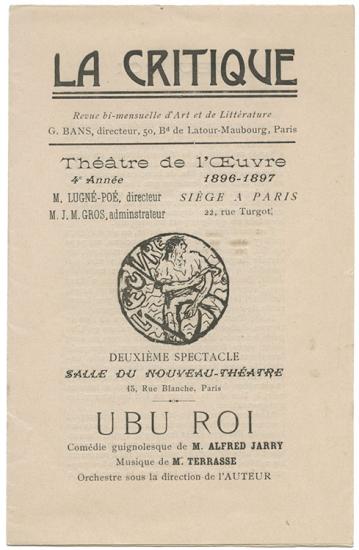

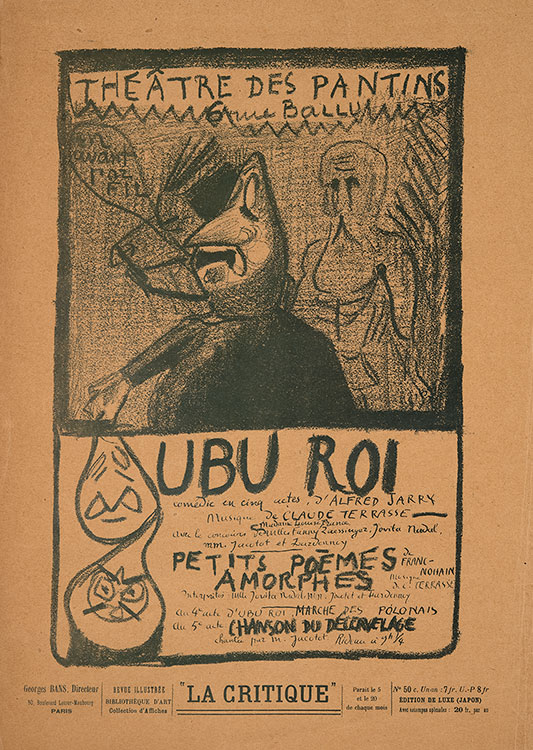

Program for Ubu roi

Jarry was in the midst of work on Perhinderion in early 1896 when he proposed a production

of Ubu roi to Aurélien Lugné-Poe, the director of the cutting-edge Théâtre de l’Œuvre. As incentive, Jarry volunteered to handle the Œuvre’s publicity and race around Paris on his bicycle to drum up subscriptions. He also helped to adapt the translation of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. Diminutive in size, Jarry played the part of a troll.

Lugné-Poe had first taken an interest in Jarry based on his experimental books and magazines. A postcard and an inscribed special copy of Les minutes in the Morgan’s collection suggest that, even as plans for Ubu roi were underway, the author continued to use his publications to gain the director’s confidence. Jarry’s determination to bring an equal degree of innovation to the stage, however, began to test Lugné-Poe. He was wary of Jarry’s reputation as an eccentric and was baffled by the play. He was on the verge of canceling the project until Rachilde assured him that, no matter what, Ubu roi would be a sensation. On 9 and 10 December, 1896, Rachilde’s prediction came true. It was a succès de scandale.

Program for Ubu roi at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre (Paris: La Critique), 1896. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray fund, 2019. PML 198466.

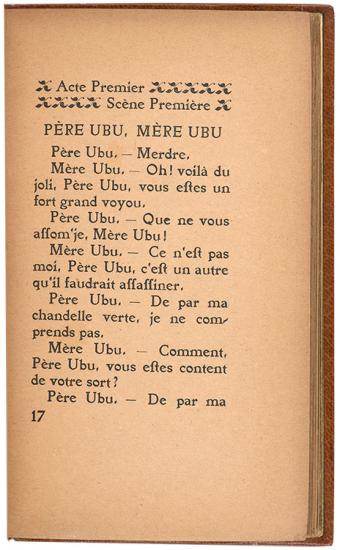

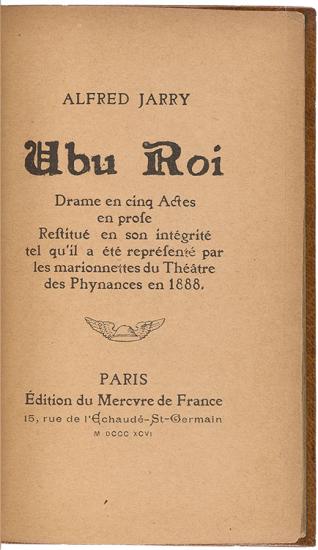

Ubu roi

Profanity was a common occurrence on cabaret stages in the 1890s. Jehan Rictus and Aristide Bruant were well-known for using what was then euphemistically called the “mot de Cambronne.” That a serious actor uttered a word that sounded like “shit” on the stage of a formal theater was something else altogether. The crowd booed and whistled for around fifteen minutes when Firmin Gémier delivered his first line; another lengthy interruption occurred later in the play when an actor’s hand served as a doorknob. The shouting doubled in volume after Gémier said Jarry’s name at the curtain.

Jarry had published an essay on the theater a few weeks before the premiere to prepare critics for Ubu roi. His radical ideas were summed up in the title: “The Futility of the Theatrical in the Theater.” For Jarry, actors and naturalist sets were the most “hideous and incomprehensible objects” cluttering the stage. He advocated for minimal props, to be moved around by handlers in plain sight. The use of cardboard masks and unnatural voices could transform performers into symbols, almost like letterforms, to express the writer’s ideas. By dispensing with the illusion of reality, a figure on stage could be a “walking abstraction” in service to the creator’s vision.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197019.

Program for Ubu roi

Jarry was the only playwright at the Œuvre to illustrate his own program (though uncredited, he also served as Ubu roi’s director and conceived its costumes and sets). His unusual design placed the actors’ names sideways, emphasizing the list of characters’ names instead. This is one of Jarry’s few depictions of Ubu without a spiral on his belly or a toilet-brush scepter in his hand. His distorted, mechanical arm holds a bag of money; the other bears a flaming candle or torch similar to the one held by the central figure in Rousseau’s painting La guerre.

Jarry’s addition of a leaf atop Ubu’s head would have been recognizable as an allusion to caricatures of Louis-Philippe I as a pear. The audience may have struggled to make sense of the burning house and the spheric creature, however. The kneeling men at the bottom left were copied from a late medieval woodcut Jarry had appropriated previously for his book César-antechrist.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), program for Ubu roi, 1896, lithograph. Collection Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University. Museum Purchase. Photography by Peter Jacobs

Ubu roi

Jarry’s revolt against norms onstage was equally apparent in his design for Ubu roi’s publication. The book was typeset in his Renaissance-style font, Perhinderion. The play’s lengthy subtitle, which referred to its origins as a high-school marionette play, was another echo of Renaissance printing practices. Jarry’s presentation of the seminal text of modern theater—with its radical mise-en-scène and shocking neologisms—was arcane, resembling early editions of canonic prose more than cutting-edge drama. It appeared six months before the play’s premiere.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197019.

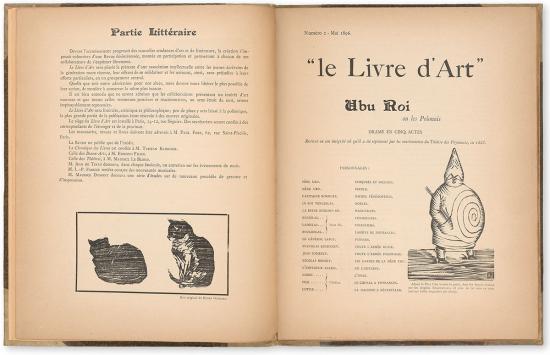

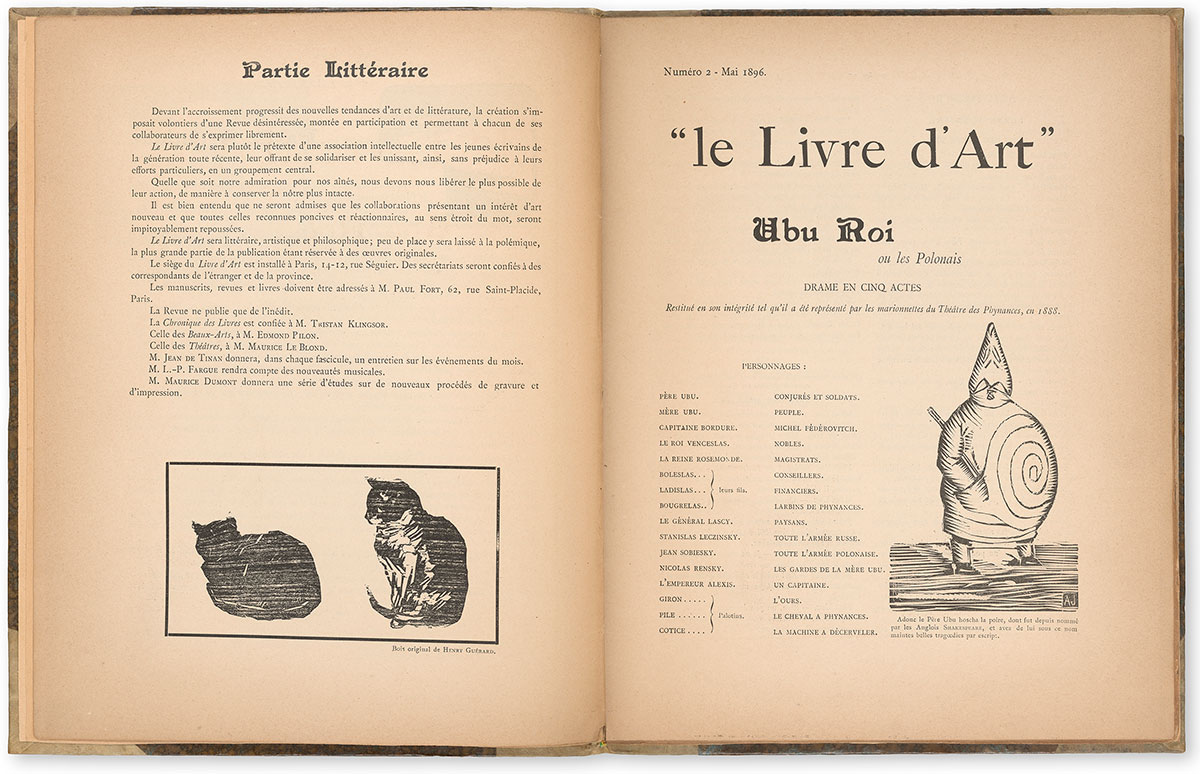

Livre d’Art

The woodcut portrait of Ubu that Jarry used as the book’s frontispiece was starkly modern in contrast with the book’s design. It had already appeared

The woodcut portrait of Ubu that Jarry used as the book’s frontispiece was starkly modern in contrast with the book’s design. It had already appeared

in the play's serialization in an avant-garde magazine that promoted the artistic revival of the woodcut.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), “Ubu roi,” in Livre d’Art no. 2 (April 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197088.

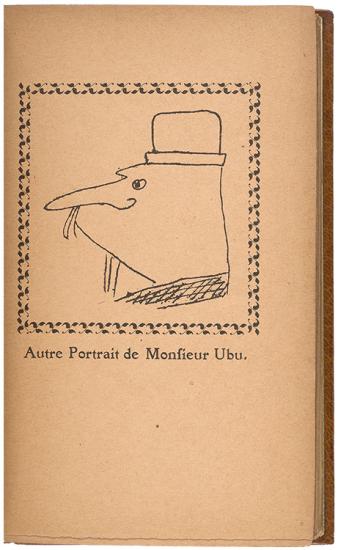

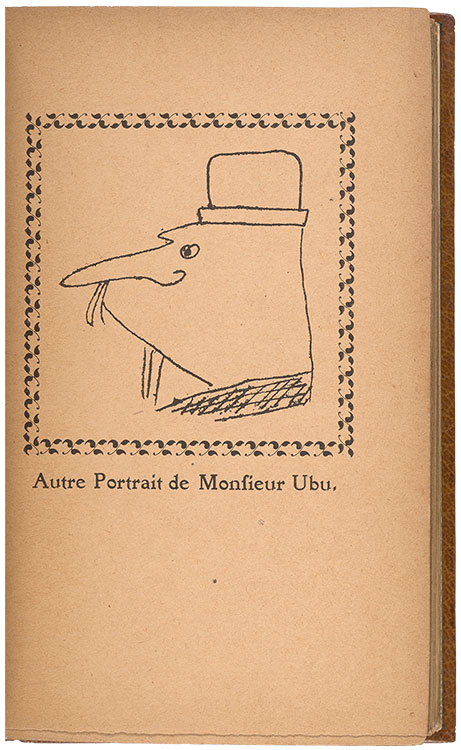

Autre Portrait de Monsieur Ubu

When Jarry reprinted the crude woodcut in the first edition, he also added this second portrait—a more cartoonish image of Ubu. That the images looked nothing alike introduced the pataphysical concept of the equivalence of opposites into the realm of contemporary illustration.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197019.

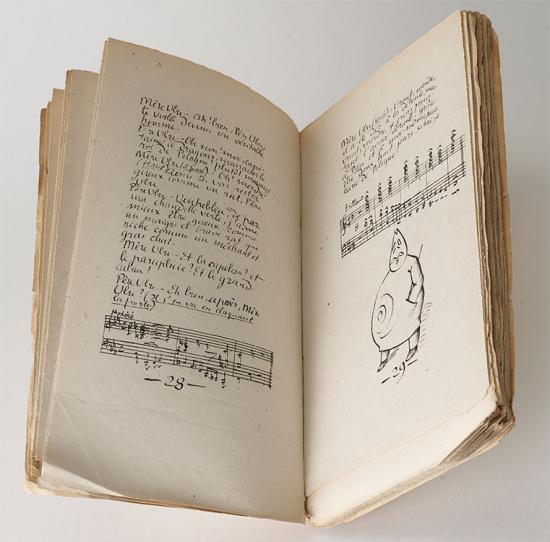

Ubu roi, texte et musique

Jarry capitalized on Ubu roi’s notoriety by issuing a facsimile of the manuscript the following year. For the edition, he rendered in pen and ink the text, title, and every ornament as well as his two portraits of Ubu. He also incorporated Claude Terrasse’s incidental music and shared credit with the composer on the cover. Jarry used the opportunity to describe his ambitious plans for an orchestra—which, in performance, had amounted to little more than a piano and some timpani.

Of his cycle of full-length plays—Ubu roi, Ubu enchaîné, and Ubu cocu—only the first was performed during Jarry’s lifetime. Ubu enchaîné was published in 1900, however, as an addendum to the second edition of Ubu roi. This version bore no traces of Jarry’s idiosyncratic illustrations or inventive book design. By that point, Jarry had switched publishers and had ceded the role of Ubu’s iconographer to Terrasse’s brother-in-law, the painter Pierre Bonnard.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Claude Terrasse (1867–1923), Ubu roi, texte et musique, facsimile autographique (Paris: Mercure de France, 1897). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197020.

L'amour absolu: roman

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the practice of publishing facsimiles of manuscripts became a trend for Symbolist writers. The movement’s chief poet, Stéphane Mallarmé, had issued his manuscript of Poésies in a photo-lithographed edition of 40 copies in 1887. Jarry’s friends Rachilde, Marcel Schwob, and Remy de Gourmont followed suit. When Jarry could not find a publisher for L’Amour absolu, he paid to produce his novel in this fashion in an edition of fifty copies.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), L'amour absolu: roman ([Paris: Mercure de France, 1899]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197024.

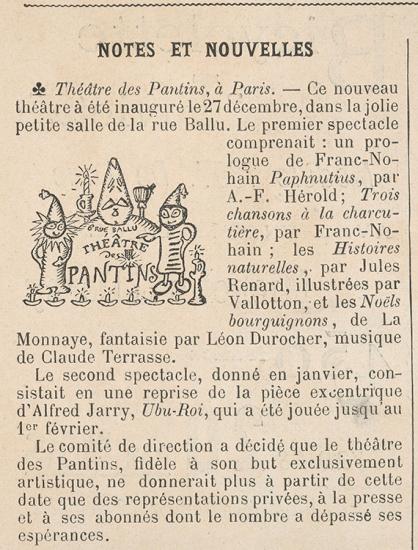

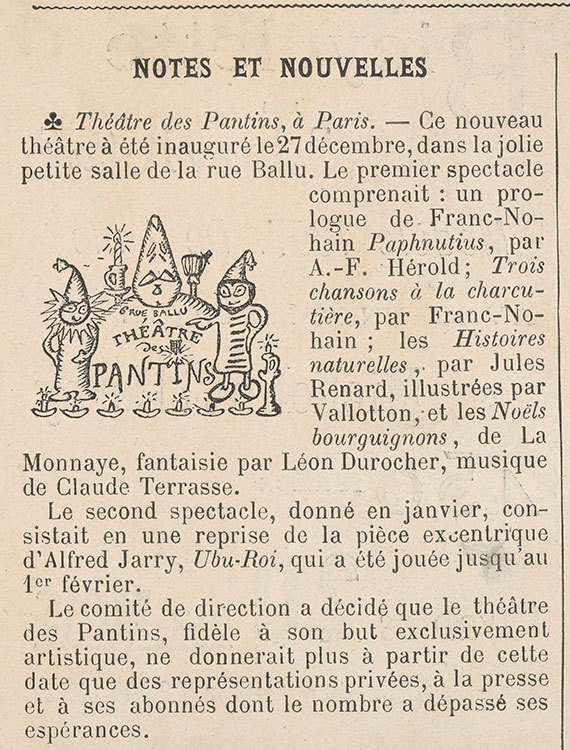

Théâtre des Pantins

"Notes et nouvelles: Théâtre des Pantins, à Paris," Revue encyclopédique Larousse (5 fév. 1898), p. [9]. Private collection.

Théâtre des Pantins

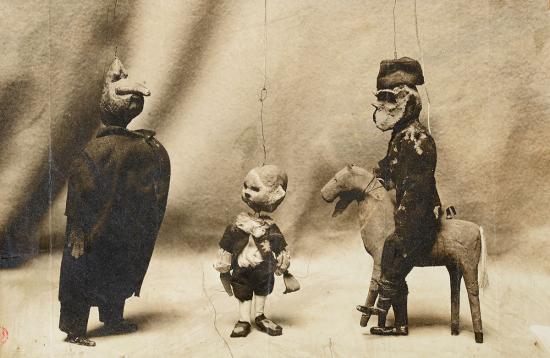

Jarry adapted Ubu roi for an avant-garde marionette theater he cofounded in 1897 with the painter Pierre Bonnard, the composer Claude Terrasse, and the writers Franc-Nohain and A.-F. Herold. The Théâtre des Pantins mounted their shows in the atelier behind Terrasse’s house. Edouard Vuillard and Bonnard painted the walls and Jarry and Franc-Nohain acted as chief puppeteers. Bonnard also built the marionettes with the exception of Ubu, which Jarry created himself.

Censorship had not been an issue at the Œuvre because it was a subscribers’ theater. The Pantins was open to the public, however, so the company had to submit the script to a bureaucrat for review (predictably, his scatological neologism “merdre” was cut). This shorter version of Ubu roi for marionettes was never published. There were three performances.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), program for Ubu roi at the Théâtre des Pantins, 1898, lithograph. Collection Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University. Museum Purchase, David A. and Mildred H. Morse Art Acquisition Fund. Photography by Peter Jacobs

Marionettes

Photographs of the marionette of Ubu created by Charlotte Jarry (1865–1925), ca. 1888-89, in Les soirées de Paris, no. 24 (1914). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197215.

Marionettes

Marionettes created by Alfred Jarry and Pierre Bonnard for the Théâtre des Pantins, ca. 1897–98. Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet, Paris.

Marionettes created by Alfred Jarry and Pierre Bonnard for the Théâtre des Pantins, ca. 1897–98. Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet, Paris.

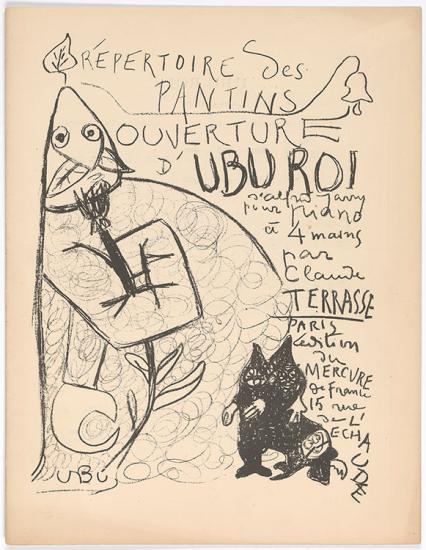

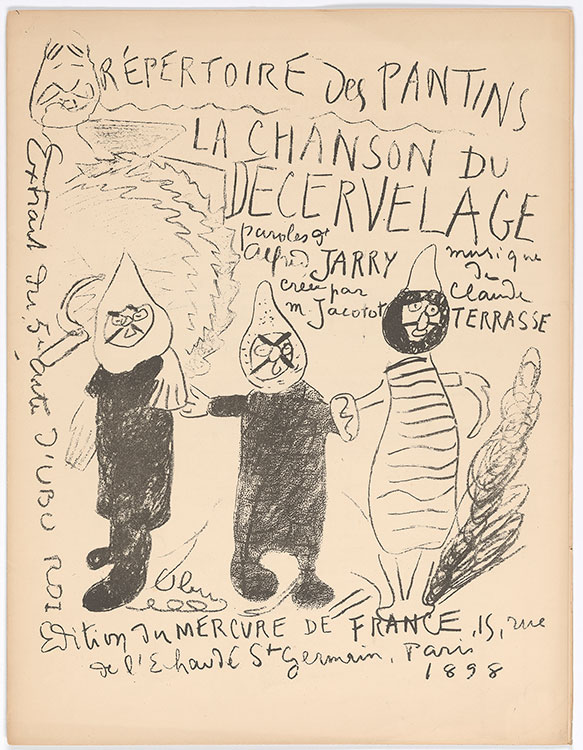

Ouverture d’Ubu roi

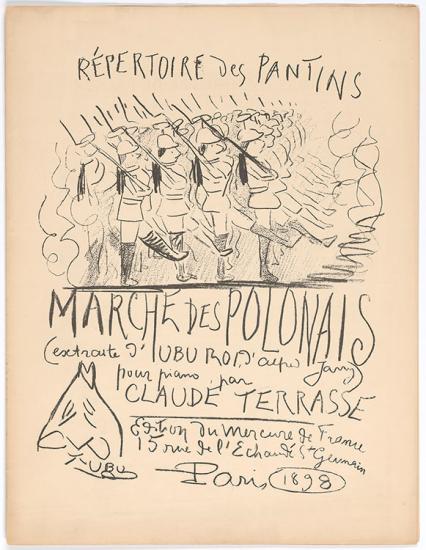

Claude Terrasse’s incidental music for the Théâtre des Pantins’ puppet shows outlasted the short-lived endeavor. Individual songs were issued as sheet music with striking lithographed covers designed by Jarry and Bonnard.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Claude Terrasse (1867–1923), Répertoire des Pantins: Ouverture d’Ubu roi (Paris: Mercure de France, 1898). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197089.

Marche des polonais

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Claude Terrasse (1867–1923), Répertoire des Pantins: Marche des polonais (Paris: Mercure de France, 1898). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197090.

La chanson du décervelage

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Claude Terrasse (1867–1923), Répertoire des Pantins: La chanson du décervelage (Paris: Mercure de France, 1898). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197091.

Ubu sur la butte

After the Théâtre des Pantins folded, Jarry adapted the play yet again for low-brow hand puppets at the rowdy Cabaret des Quat’z’arts in Montmartre. Ubu sur la butte, as he later titled it, ran for sixty-four performances in 1901. For the scenario, Jarry cannibalized Ubu roi to reduce the play to two acts. The substantial changes he made reflected his anticipation of censorship and respect for the cabaret milieu. Like most puppet shows, the new version breached the fourth wall with a dialogue between the director and the archetypal puppet Guignol, who also referenced the cabaret and its spectators.

Five years later, Jarry published Ubu sur la butte as part of his booklet series he called Théâtre mirlitonesque—a term comparable to “ridiculous theater.” For the title page and cover designs, he copied the architectural frame on the 1535 title page of François Rabelais’s Gargantua—published in Lyon, the birthplace of the hand-puppet tradition—but used mirlitons, which are a kind of kazoo, in place of Rabelais’s classic columns.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu sur la butte, Théâtre mirlitonesque (Paris: Sansot et Cie, 1906). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197031.

Le moutardier du pape

Over a decade, Jarry composed librettos for at least ten operettas. Most remained unfinished or were printed posthumously. Par la taille would be the second and last title to appear in Jarry’s whimsical Théâtre mirlitonesque book series in 1906. In 1907, his friends helped organize a deluxe publication of his comic opera Le moutardier du pape—a farcical retelling of the legend of Pope Joan, who disguised herself as a man. The book’s design united a pensive (much younger) portrait of Jarry with eleven-year-old images of Ubu, who has no role in the operetta.

Similar to Jarry’s ahistorical approach to book design, his comic operas contain anachronistic figures and technologies. Photography and the Salvation Army are invoked within the ninth-century setting of Le moutardier, which also features a telephone. The title character tells Joan he is going to make a call “without a line,” adding, “for the time being, pending its invention.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Le moutardier du pape: Opérette bouffe en trois actes (Paris: s.n., 1907). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197034.

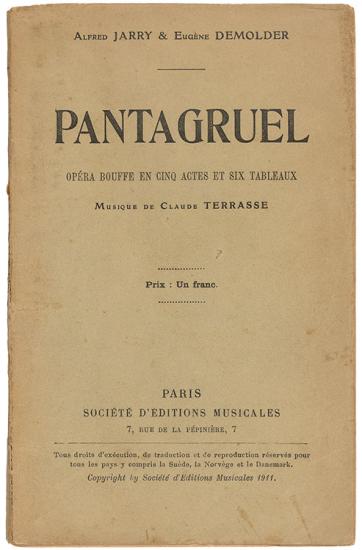

Pantagruel

Characters in Jarry’s comic operas are empty vessels, similar to marionettes. As one scholar phrased it, the subject of these librettos is arguably language itself. Jarry’s paragon in the linguistic arts was François Rabelais. For eight years, Jarry labored to turn Rabelais’s Pantagruel into an operetta. By 1904, however, his health had declined, exacerbated by alcoholism and poverty. Pantagruel’s composer, Claude Terrasse, persistently pressed Jarry to make progress on the libretto. He lured the writer to his country house to help him dry out and finish the text, but neither plan was successful (a friend completed the libretto after Jarry’s death). The fanciful baroque sets and costumes used in its 1911 premiere proved to be the antithesis of the anti-naturalist mise-en-scène that defined Jarry’s career.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) and Eugène Demolder (1862–1919), Pantagruel: Opéra-bouffe en cinq actes et six tableaux, musique de Claude Terrasse (Paris: Société d’éditions musicales, 1911). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197036.

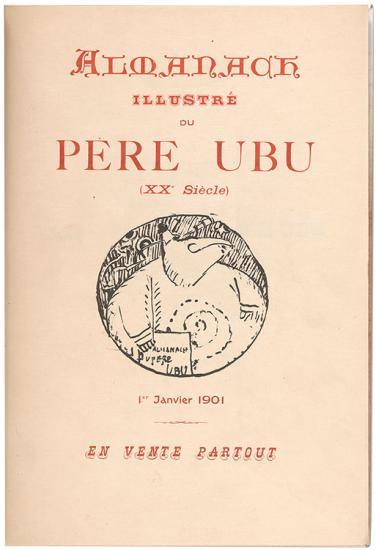

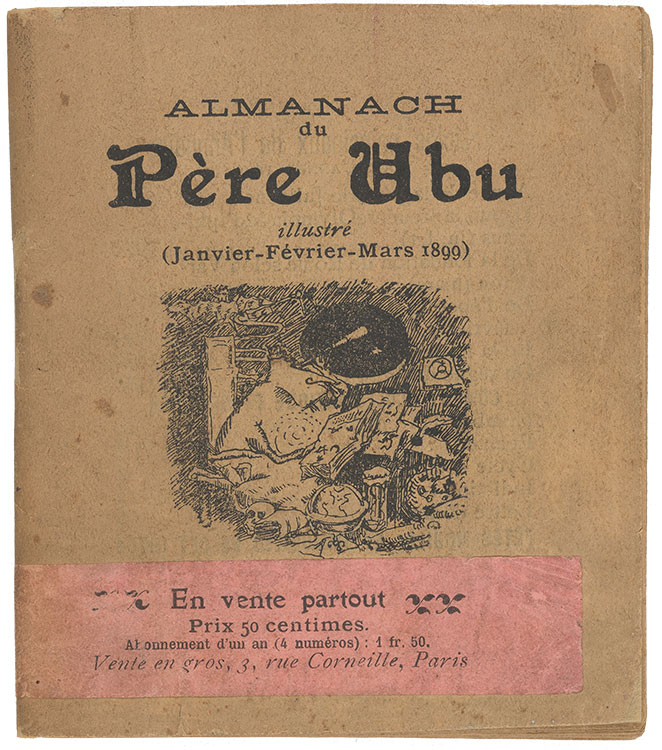

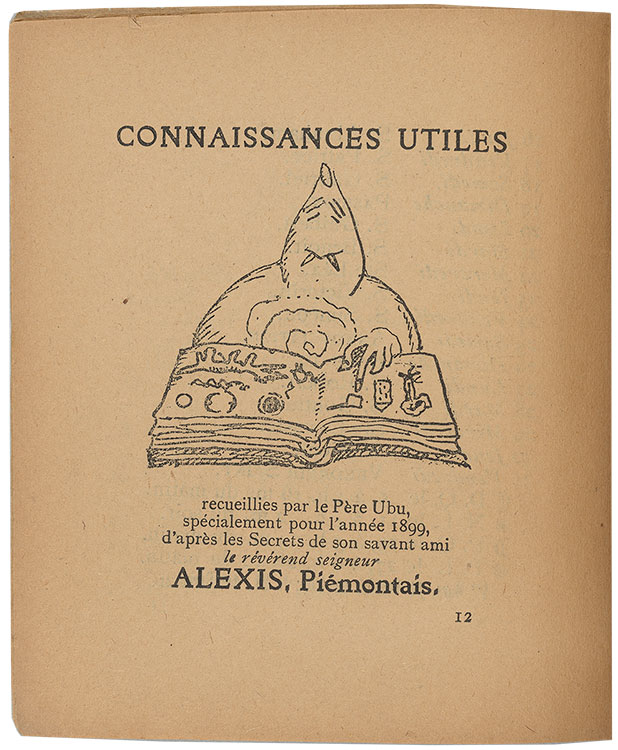

Almanach du Père Ubu illustré

Ubu returned to print for Jarry’s reinvention of a centuries-old genre: the common almanac. Both the author and the illustrator, Pierre Bonnard, were uncredited. Jarry applied his own approach to illustration when composing the texts by assembling original material with passages appropriated from old books. There were new playlets as well as sixteenth-century recipes for dyeing one’s hair green (supposedly something Jarry himself did on one occasion). The religious calendars—a requisite of early almanacs—listed the feast dates celebrating genuine saints as well as Saint Merdre. Another requisite of the genre, astronomical forecasts, predicted a partial “eclipse of Père Ubu.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach du Père Ubu illustré. Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: s.n., [1898]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197025.

Almanach du Père Ubu illustré

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach du Père Ubu illustré. Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: s.n., [1898]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197025.

Almanach du Père Ubu illustré

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach du Père Ubu illustré. Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: s.n., [1898]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197025.

Almanach du Père Ubu illustré

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach du Père Ubu illustré. Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: s.n., [1898]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197025.

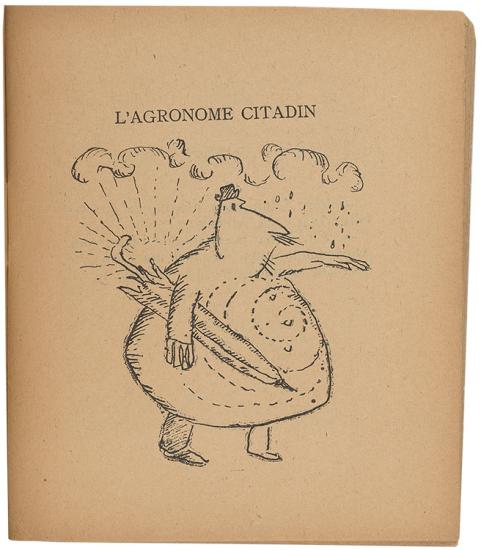

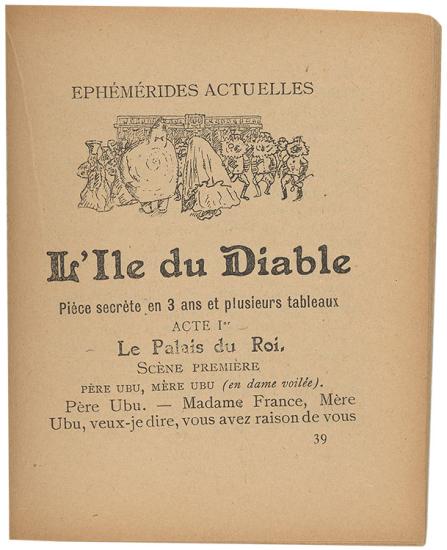

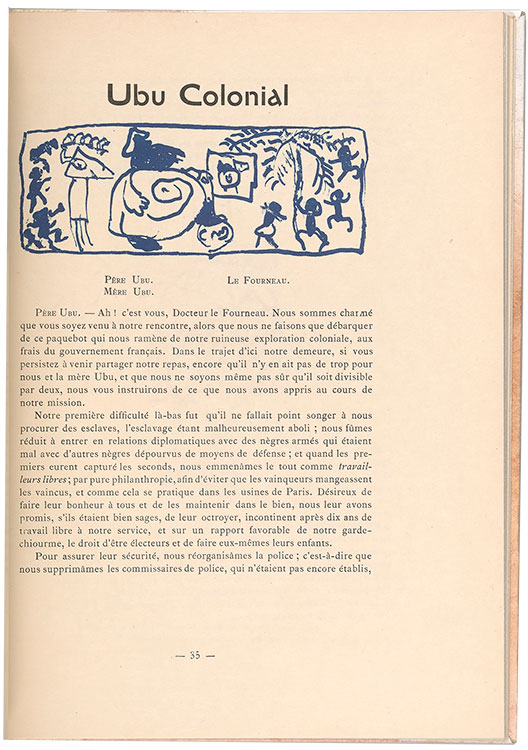

Île du Diable

Jarry’s most overt political commentary surfaces in the Ubu almanacs. The play Île du Diable (Devil’s Island), included in the first almanac, dramatizes events related to the Dreyfus affair. Ubu is cast as an effigy of the corrupt French military. The character would stand in as a proxy for France itself in the second almanac’s Ubu colonial, which comprises an account of Ubu’s visit to Africa. Jarry’s satire of the attitudes informing colonial practices was always indiscriminate, ridiculing both the perpetrators and victims of colonialism—an ambivalence affirmed by Bonnard’s offensive caricatures.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach du Père Ubu illustré. Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: s.n., [1898]). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197025.

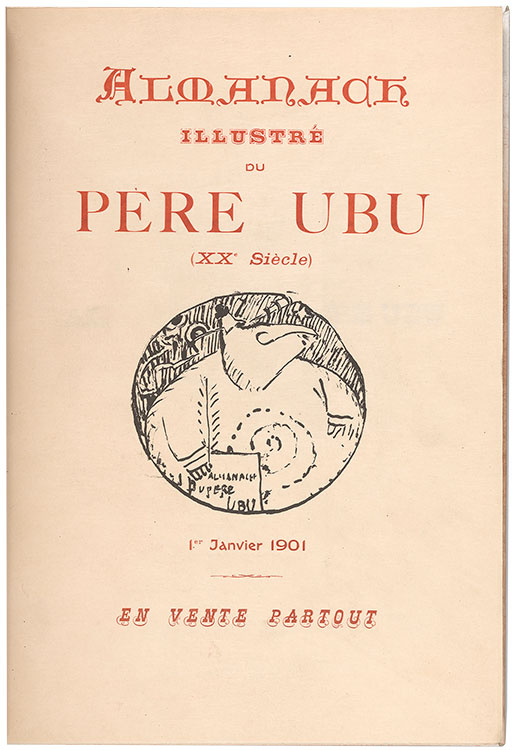

Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle), cover

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, cover. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle), pp.42-43

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, pp.42-43. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, pp.42-43. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle), p. 35

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, p. 35. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle), pp.14–15

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, pp. 14–15. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

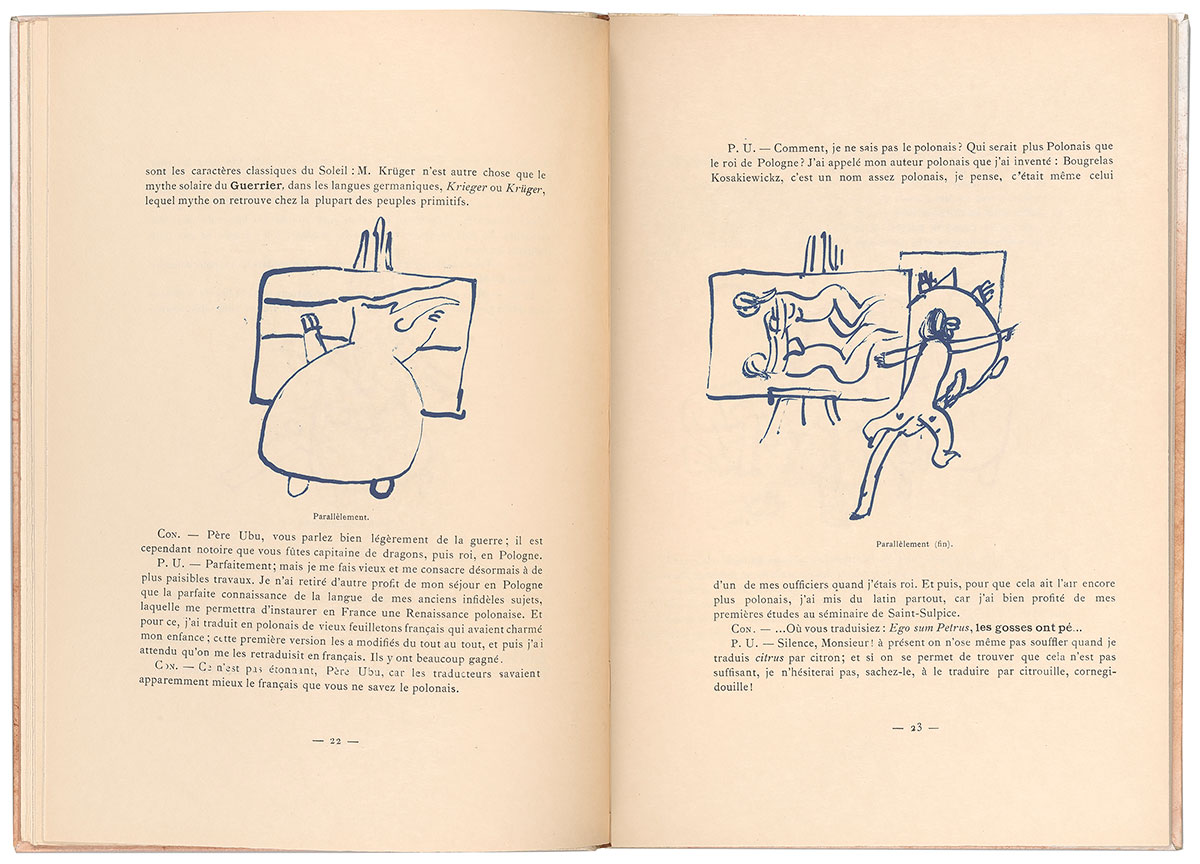

Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle), pp. 22–23

The 1901 almanac was produced in a luxurious edition, a first for Jarry. This collaborative enterprise between Jarry, Bonnard, and other friends took shape in the basement of Ambroise Vollard’s modern art gallery. The influential dealer (also the almanac’s anonymous publisher) had just begun to conceive deluxe illustrated books of poetry, now called livres d’artistes, as promotional materials for contemporary artists. Vollard’s first such project, Paul Verlaine’s Parallèlement (1900), was a showcase for Bonnard’s sensual lithographs. Jarry and the painter mocked its scandalous imagery in one of the almanac’s episodes; they also created their own suggestive text and images for several letters in “Ubu’s Alphabet.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Almanach illustré du Père Ubu (XXe siècle). Illustrations by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: [Ambroise Vollard], 1901). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197098, pp. 22–23. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Beautiful Like Literature

In the fiction and journalism Jarry published in the twentieth century, his engagement with printed matter expanded from innovations in book designs to ideations of the medium in writing. Documents, imaginary libraries, and the literature of visionary science play central roles in his tour de force, Docteur Faustroll. Subtitled “a neo-scientific novel,” the work elaborated on pataphysics for the first time and, in its sheer experimentation, forecast landmarks of literary modernism.

Faustroll and his 1902 novel, Le surmâle, also manifested Jarry’s conceptions of technology in artistic practice. His cultivation of hybrid personae throughout his life, unifying puppet and puppeteer in theater and Alfred and Ubu in real life, persisted in his exploration of the creative assimilation of man and machine. On one occasion when he casually fired a gun at another man, Jarry described the act as “beautiful like literature.” This lack of separation between artistic gestures and their presumed opposition in extreme pastimes and play suggests an equivalence between performance and life, between art and non-art—what André Breton would later characterize as a paradigmatic shift. After Jarry, the differentiation between art and life was annihilated.

© RMN-Grand Palais / Erich Lessing/ Art Resource, N.Y.

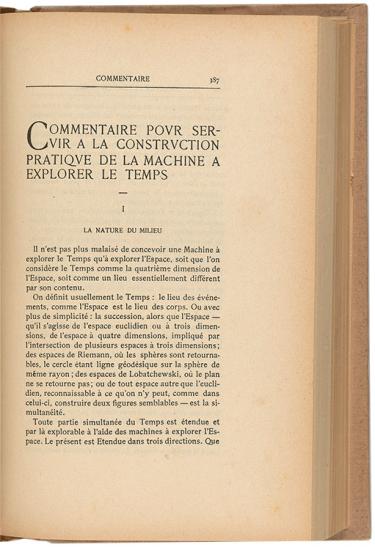

La machine à explorer le temps

Jarry showcased his rhetorical virtuosity and irreverence later in life by publishing a book’s worth of speculative essays in magazines. Among many of the subjects Jarry addressed were cannibalism, a machine to beat women, and “killer pedestrians”; his review of a new postage stamp described it as a depiction of a blind prostitute (it was in fact the female personification of the French Republic). In one of his most famous vignettes, “The Passion Considered as an Uphill Bicycle Race,” Jesus gets a flat tire after riding over a bed of thorns and has to carry his wooden cross-frame bike up a hill over his shoulder.

Soon after H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine was translated into French, an article on how to build a time machine appeared under the byline of Jarry’s fictional character, Doctor Faustroll. Jarry borrowed passages from writings by the physicist Lord Kelvin to conceive of a real machine that was a gyroscopic device, initially described as analogous to a bicycle. Most of the essay was devoted to the phenomenon of time itself. Jarry proposed an “imaginary present” and defined time travel in pataphysical terms: isolated in a machine within the luminiferous ether, past and present could be explored simultaneously. Jarry emphasized his definition of duration typographically: “Duration is the transformation of a succession into a reversion. In other words: THE BECOMING OF A MEMORY.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), “Commentaire pour servir à la construction pratique de la machine à explorer le temps,” in Mercure de France, no. 110 (February 1899). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197152.

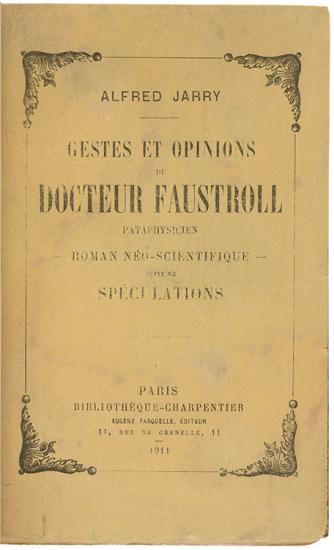

Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll

Faustroll, Jarry’s most imaginative and absurd novel, is a textual collage comprising the art, science, and people who shaped his aesthetic life. Treatises on pataphysics, legal documents, equations measuring the surface of God, and letters from another dimension are folded into a travel narrative about Faustroll, a bailiff, and a monkey whose sole utterance is “Ha Ha.” They set sail from Paris to Paris by sea on Faustroll’s copper mesh bed. Other beings on their voyage are three-dimensional elements conjured from an inventory of books Jarry calls the livres pairs (coequal or equivalent books). Twenty-fourth on that list is an anonymous play titled Ubu roi. Across “foliated space,” Faustroll draws from it “the 5th letter of the first word in the first act”—in other words, the second r in Jarry’s linguistic distortion merdre—synthesizing in one letterform (one piece of type) his radical transformation of artistic practice.

Henri Rousseau also makes an appearance in the novel: he defaces banal art with a painting machine, which eventually projects its own works on the walls of a “Palace of Machines.” Rejected by publishers, Jarry added a note to the Faustroll manuscript predicting that it would not appear in print “until the author has acquired enough experience to savor all its beauties.” The book was published four years after his death at age thirty-four.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll, pataphysicien: Roman néo-scientifique, suivi de Spéculations (Paris: Eugène Fasquelle, 1911). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197152.

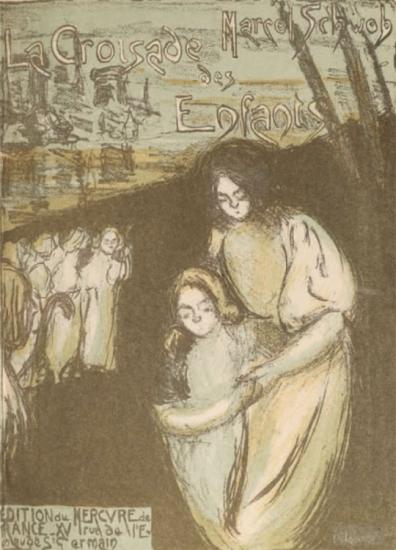

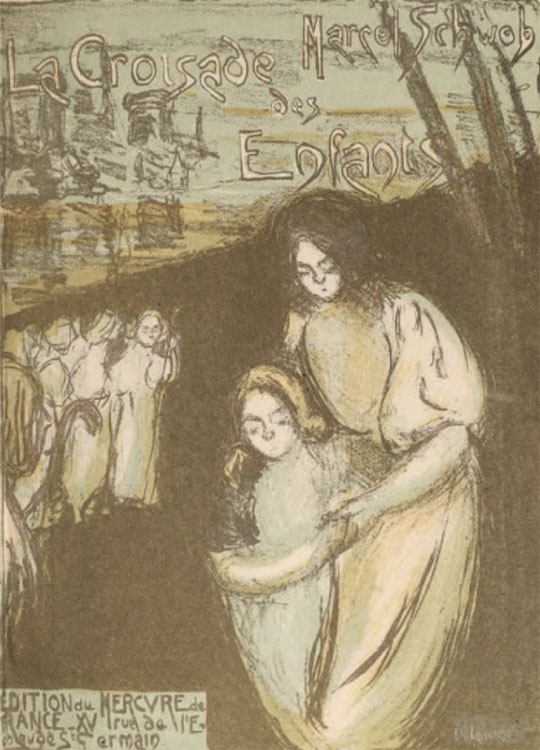

La croisade des enfants

Faustroll’s many departures from the conventions of nineteenth-century novels include Jarry’s persistent invocation of living writers and artists. Among the works Jarry draws attention to are Emile Verhaeren’s Les campagnes hallucinées, Bonnard’s poster for La revue blanche, and La croisade des enfants by the author who championed his early career, Marcel Schwob. Real scientists of the day—those prone to bizarre theories, at least— are also invoked and interwoven with explanations of pataphysics, Jarry’s “science of imaginary solutions.” In addition to the specter of Lord Kelvin, the physicist C. V. Boys looms large. Jarry used ideas from Boys’s 1890 book on soap bubbles to explain why Faustroll’s copper mesh bed was seaworthy.

Marcel Schwob (1867–1905), La croisade des enfants. Cover illustration by Maurice Delcourt (Paris: Mercure de France, 1896). The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2019. PML 198234.

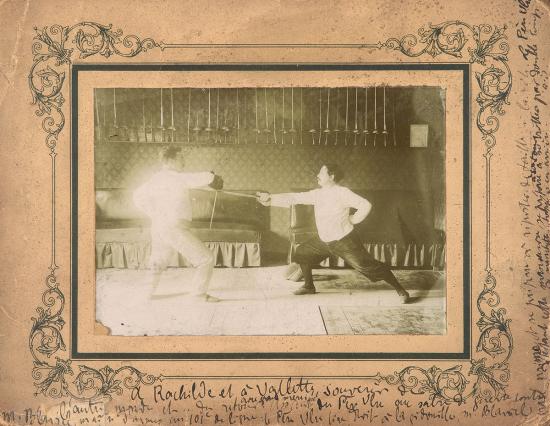

Société des vélocipèdes Clément

At a time when bicycling was transitioning from a pastime to an athletic activity, Jarry used his Clément Luxe for commutes to and from the country and for intracity transportation. He exalted bicycles as a “new organ” for man and an extension of the skeleton. Kinetic man-machines, when ridden at top speed, had the potential, Jarry suggested, to transform the artist’s consciousness. Guns, fencing foils, and even fishing rods seemed to function the same way in Jarry’s pursuit of extreme recreation. All were inextricable from his artistic identity in his final years, blurring the lines between creative expression and life.

“Catalogue illustré des célèbres cycles Clément,” Société des vélocipèdes Clément, no. 4 (1895). Collection of Pryor Dodge.

Alfred Jarry fencing

Unidentified photographer, Alfred Jarry (at right) fencing with his teacher Félix Blaviel in Laval, 1906. The Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection.

Le surmâle

Encounters between man and technology in Le surmâle take on perverse and morbid characteristics. In the novel, a “love-inspiring-machine” electrocutes the hero after he demonstrates his supermale status by engaging in sex eighty-two consecutive times. The novel also features a ten-thousand-mile race between a locomotive and a five-man tandem bike. The riders are fueled with “perpetual motion food”—a compound chiefly comprised of strychnine and alcohol. Midway through the race, one of the cyclists dies; the corpse, whose feet are strapped to the pedals, continues on, however, and the “human mechanisms” outlast the train.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Le surmâle: Roman moderne. Cover illustration by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (Paris: Fasquelle éditeurs, 1970). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197614. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Vins en gros

Used in the extreme, “recreational” drugs—absinthe, wine, and ether—were devices Jarry used to supplement his imagination like a form of artificial intelligence. They also sapped his health and finances. After the magazines he depended upon for income folded, Jarry’s reputation as a delinquent in pecuniary matters became more pronounced. This envelope, addressed to Jarry by his wine merchant, contained one of the many outraged, threatening demands for payment overshadowing his final year. Jarry may have been intoxicated when he scrawled an indignant untruth on the back of the same envelope: “I always pay my debts.”

Envelope addressed by Gaston Jobard to Alfred Jarry, stamped 3 October 1907. On verso: Letter from Jarry to Jobard, October 1907. Collection of Christophe Champion, Librairie Faustroll.

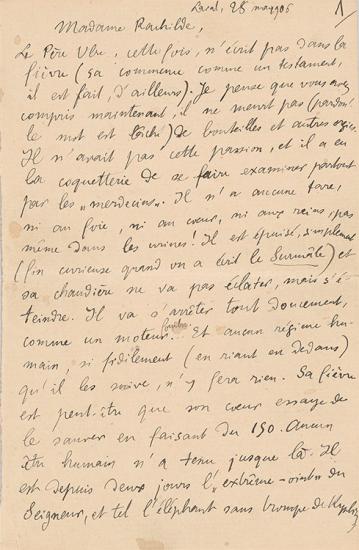

“The Testament of Père Ubu”

In 1906, Jarry believed he was on the verge of death and wrote a letter to Rachilde that is now referred to as “The Testament of Père Ubu.” Jarry asks her to undertake a “posthumous collaboration” by finishing his novel after he dies. Writing about himself as Ubu in the third person, he concedes the irony that the author of The Supermale is now spent. Ubu’s furnace “is not going to explode, but rather just switch itself off . . . quite calmly, like an exhausted motor.” Jarry compares Ubu’s brain to a “perpetual machine” that will persist and dream without him. “He left such beautiful things on earth,” adds Jarry,“but he is disappearing in such an apotheosis! . . . He has armed himself before Eternity and is not afraid.”

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), letter to Rachilde, 28 May 1906 (“The Testament of Père Ubu”). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. MA 9074.

Prophet of the Avant-Garde

You are free to see in Mister Ubu as many allusions as you like, or, if you prefer, just a plain puppet, a schoolboy’s caricature of one of his teachers who represented to him everything in the world that is grotesque.

—Alfred Jarry, address to the audience at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre, 1896

In a career spanning just thirteen years, Jarry produced an eclectic body of work that has reverberated in the art and literature of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Writers and artists have drawn upon Jarry’s work at moments of historical and cultural change, most acutely on the eve of the Second World War and at the advent of counterculture movements in Europe and America. A metaphor for political corruption and injustice, Ubu—like the spiral on his belly—is also a symbol of pataphysics and its infinite applications in the conception of alternative realities. The character also stands in for the author himself as an oracle of life’s absurdities and as an icon of the subversive imagination. Jarry’s adoption of Ubu as an alter ego, paralleled in his use of puppets, technology, and appropriated texts and imagery as “original” works of art, continues to resonate in the indirect gestures of the readymade and other idea-based art. Works in this section point to some of the evidence of Jarry’s continuing legacy in the modern era.

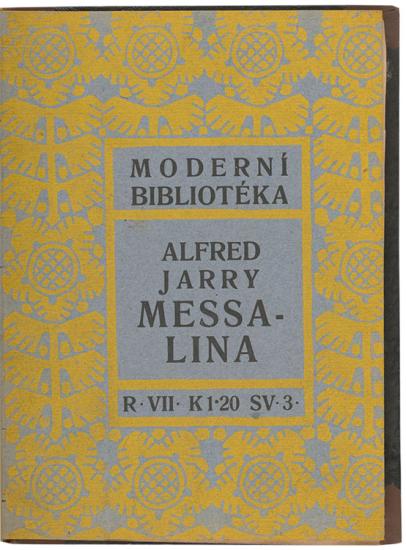

Messalina

Oscar Wilde and Arthur Symons drew attention to Jarry’s works in England during his lifetime; and the Scandinavian poet Sophus Claussen made an aborted attempt to translate Ubu roi into Danish. It was in Prague, however, where the first full translation of Jarry’s work appeared. His novel Messaline (1903) was serialized in 1904 in Arnošt Procházka’s seminal journal of the Czech avant-garde, Moderní revue, and was issued by the magazine’s imprint in book form in 1908. Jarry’s works would continue to hold sway in Central and Eastern European countries throughout the twentieth century as a touchstone for artists’ responses to totalitarian regimes.

For the subsequent generation of artists and writers, Jarry’s iconoclasm came to define the ethos of the modern avant-garde. His influence owes much to his encounter with the Italian Futurist poet, F.T. Marinetti (1876–1944), and close friendship with Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918), the poet who would coin the terms cubism and surrealism. Marinetti called Jarry “the unquestionable literary genius of the underworld.” It was Apollinaire’s accounts of Jarry after his death, however—the gun-waving antics and eccentric lifestyle and dress—that left an indelible mark on the latter’s legacy.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Messalina ([Prague]: Moderní bibliotéka, 1908). The Morgan Library & Museum, anonymous gift for the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection, 2017. PML 197675. Anonymous gift, 2017.

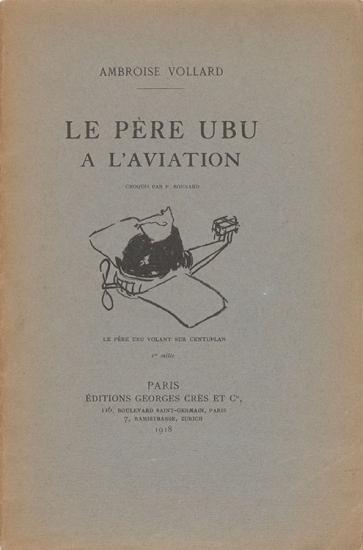

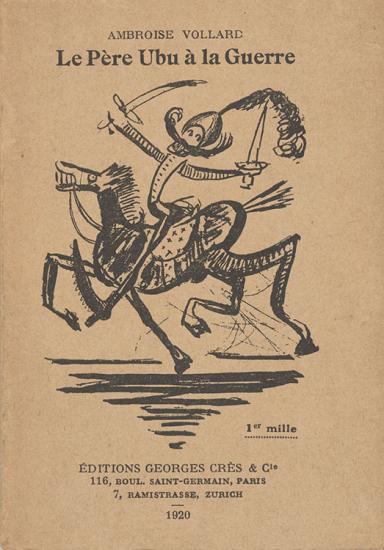

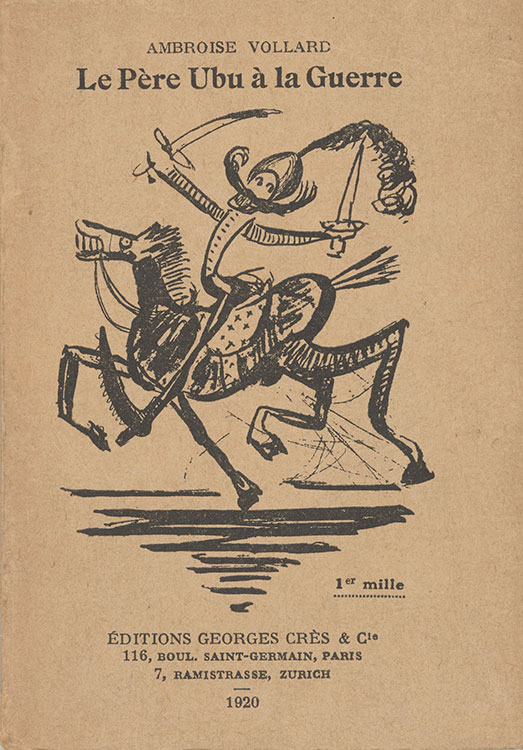

Ambroise Vollard

Ambroise Vollard—gallerist, publisher, and friend to Jarry—wrote comedic texts featuring Ubu during and after World War I. A symbol of collective tyranny and of the mindless mob, Vollard’s Ubu appears in colonial settings, hospitals, and battlefields. To illustrate his series of publications, Vollard called upon artist friends with radically different aesthetics: Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), Jean Puy (1876–1960), and Georges Rouault (1871–1958).

Ambroise Vollard (1867–1939), Le Père Ubu à l’aviation. Cover illustration by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), (Paris: Éditions Georges Crès et cie, 1918). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197109. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Le Père Ubu à la guerre

Ambroise Vollard (1867–1939), Le Père Ubu à la guerre, dessins de Jean Puy (Paris: Éditions Georges Crès et cie, 1920). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197113.

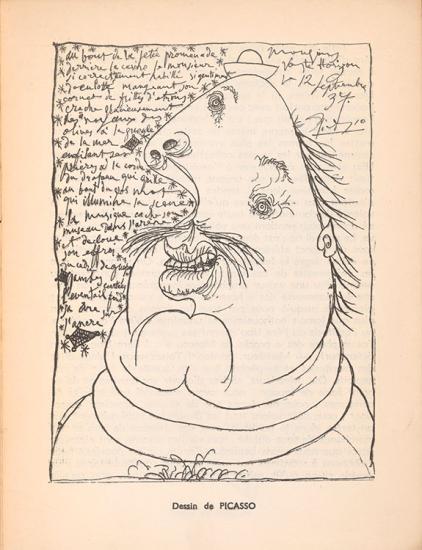

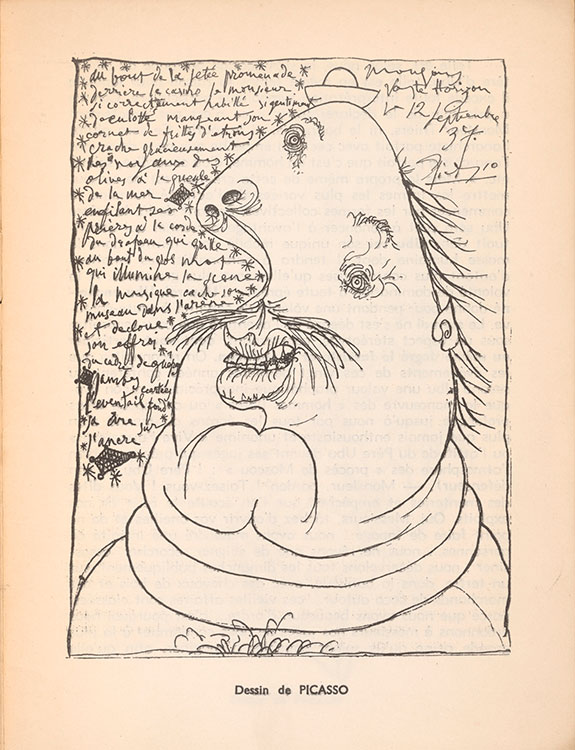

Pablo Picasso

Legends surfaced, proliferated by Apollinaire and Max Jacob (1876–1944), among others, about encounters between Pablo Picasso and Jarry. Some were undoubtedly apocryphal; they were made further credible, however, by the number of sketches of Ubu and Jarry that Picasso left behind. The painter used Ubu as a symbol for injustice and oppression during the political upheavals of the 1930s, especially those wrought by the Spanish general, Francisco Franco. As Picasso became more proficient in French, he learned passages of Jarry’s plays by heart and collected his manuscripts and other artifacts, even claiming that his pet owls were ancestors of Jarry’s birds.

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), illustration, in Ubu enchaîné (Paris: s.n., 1937). The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2018. PML 198110. © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

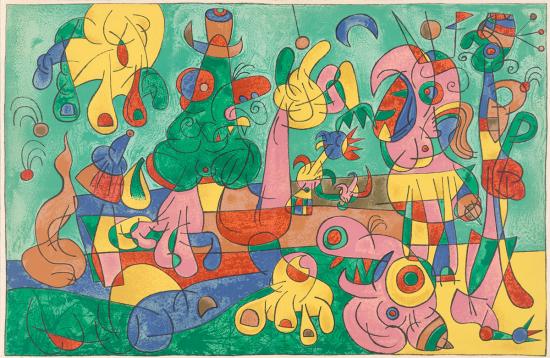

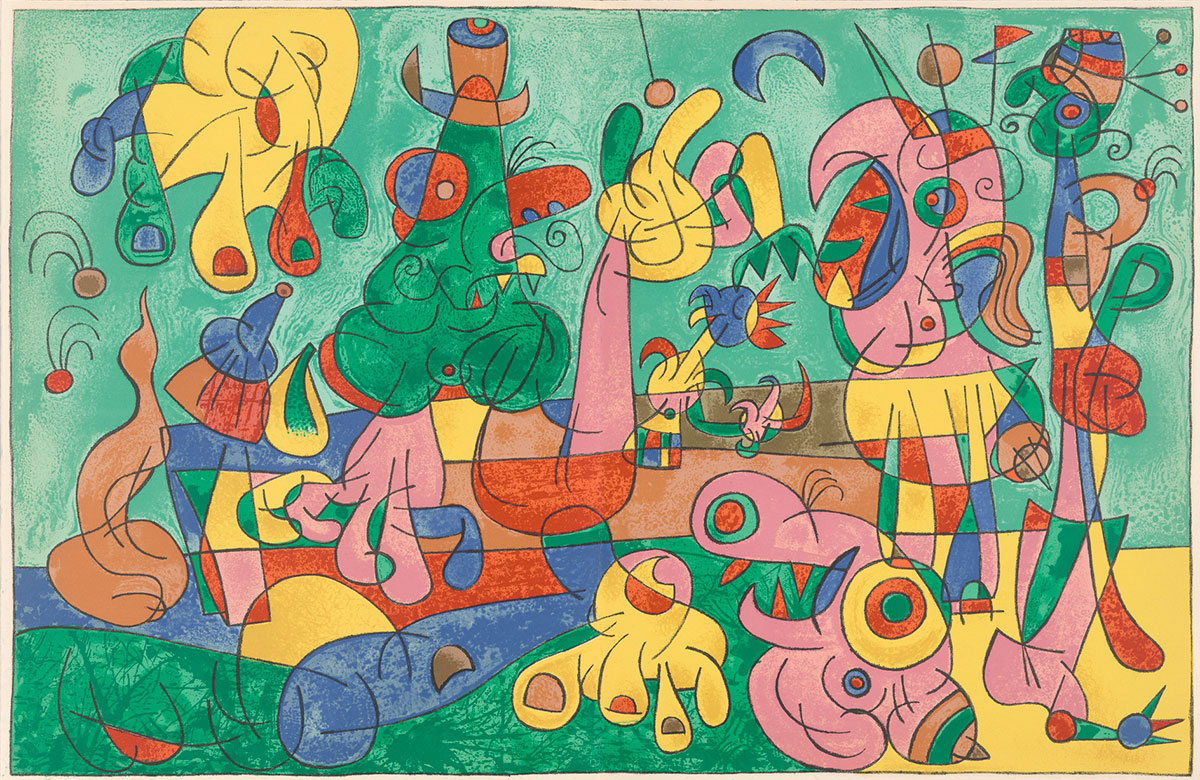

Joan Miró

On the fortieth anniversary of Jarry’s death, Joan Miró (1893–1983) signed a contract to illustrate Ubu roi. The ambitious edition took two decades to complete. The Catalan painter had been drawn to Jarry’s work since the 1920s, not only his most celebrated play but also his drawings, theoretical writings, and the novels Docteur Faustroll and Le surmâle. For Miró, as for Picasso, Ubu symbolized the corruption of the Franco regime in Spain. As he grew older, he expanded his interpretation of the character in projects both sinister and playful, creating his own adventures that imagined Ubu’s childhood. Eventually, Miró’s conception of Ubu came to encompass all that was base in humanity—including, the painter once said, the art market.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi, lithographies originales de Joan Miró (Paris: Tériade éditeur, 1966). The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman, 2017. PML 197100. © Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris 2019.

Dora Maar

Maar is known for her beautiful and surreal black-and-white photomontages, which often combine street photography with erotic fragments of the female body. This image of an armadillo fetus is exceptional in her oeuvre for its repellent qualities. Maar’s original title for the work was Portrait d’Ubu. At the first exhibition of Surrealist objects in Paris in 1936, the curators grouped the photograph with “interpretations of found objects.” Throughout her life, Maar neglected to explain the subject or title of the work. Its creation coincided with her participation in Parisian radical anti-fascist movements spearheaded by the writers Georges Bataille and André Breton.

Dora Maar (1907–1997) Père Ubu, 1936, gelatin silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gilman Collection, Purchase, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, by Exchange, 2005; 2005.100.443. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

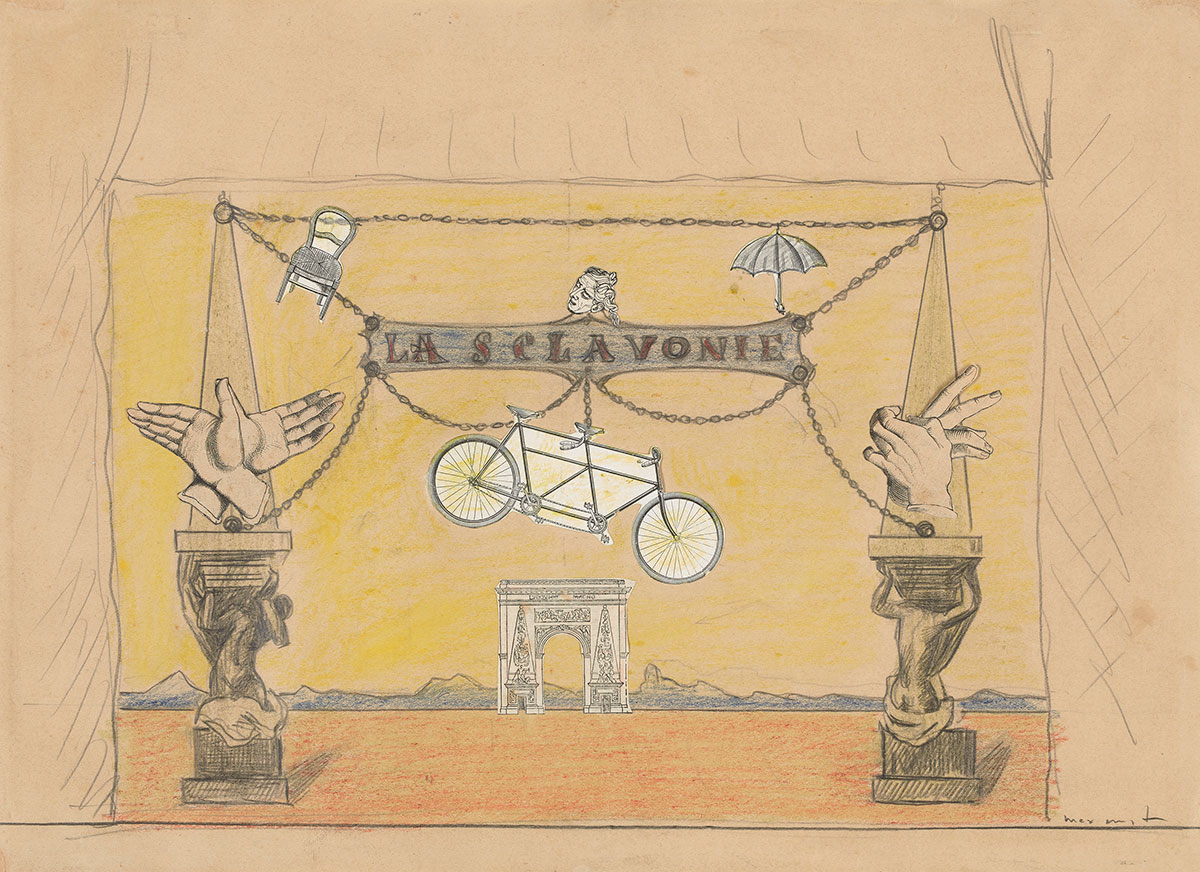

Max Ernst

The rise of nationalism was the subtext for Sylvain Itkine’s 1937 world premiere of Jarry’s 1899 play Ubu enchaîné. André Breton oversaw the design of the program, which contained texts and illustrations by Paul Eluard, Pablo Picasso, René Magritte, and other figures associated with Surrealism. Max Ernst’s set designs for the production were based on his collages of found imagery and drawings. Breton called Jarry “the master of us all.” For the Surrealists, Ubu was not only a tyrant: in their collaborative deck of tarot cards Le jeu de Marseilles, the group used Jarry’s woodcut portrait of Ubu as the joker.

Max Ernst (1891–1976), set design for Alfred Jarry, Ubu enchaîné, 1937, graphite and wax crayon, with collage of cut relief-printed papers, on tan wove paper. The Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph R. Shapiro, 1992.220. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

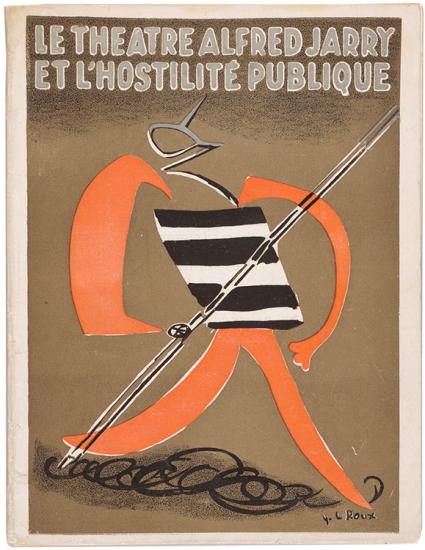

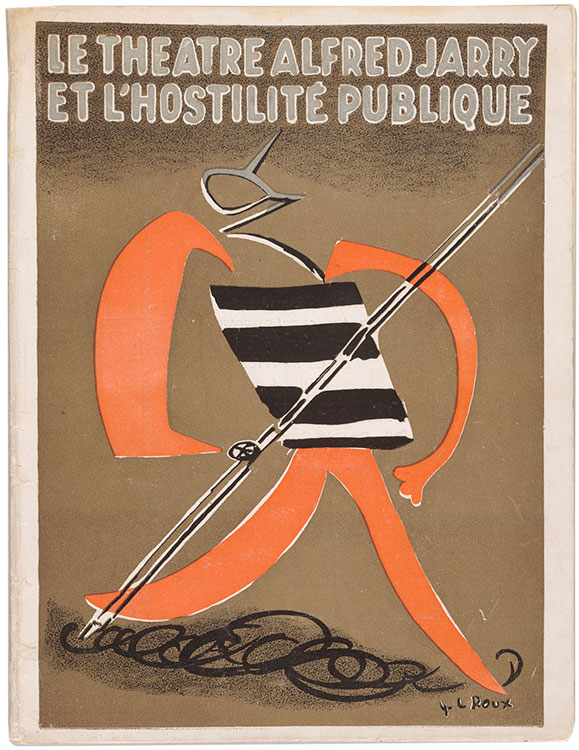

Le Théâtre Alfred Jarry et l’hostilité publique

After breaking with the Surrealists, Antonin Artaud and Roger Vitrac formed Le Théâtre Alfred Jarry, taking inspiration from Jarry’s antinaturalist theatrical philosophy and the burlesque brutality of performance inherent in Ubu roi. This booklet, which served as a manifesto as well as a complete history of the company, appeared just after hostile reactions in the press and among their peers had caused the group to disband. The section documenting critics’ blurbs used quotations from both real and fictional reviews (a few opinions were attributed to Père Ubu).

Antonin Artaud (1896–1948) and Roger Vitrac (1899–1952), Le Théâtre Alfred Jarry et l’hostilité publique, cover illustration by G.-L. Roux (1904–1988) [Paris: s.n., 1930]. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2017. PML 197100.

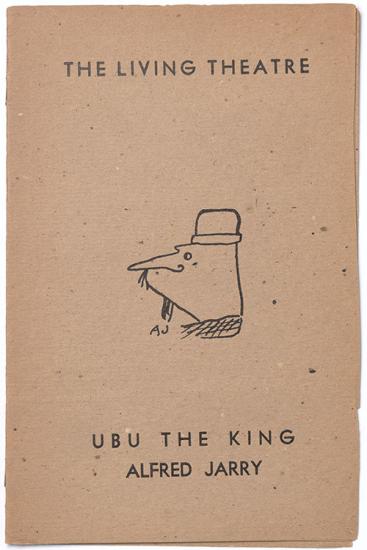

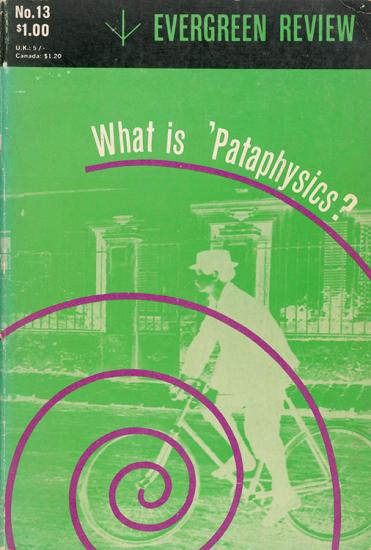

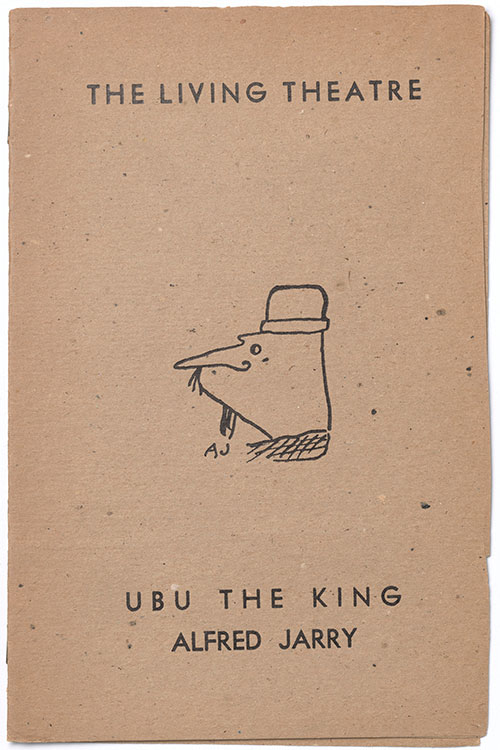

Ubu the King

After the Second World War, Jarry’s identification as a provocateur and an icon of free expression made him a touchstone for burgeoning countercultural movements. Underground magazines such as Free Unions, Evergreen Review, and Gnaoua featured translations of his work as a bridge spanning late Surrealism, the Theatre of the Absurd, and experimental literature of the 1950s and 1960s. The Living Theatre, founded in New York by Judith Malina and Julien Beck, used one of Jarry’s drawings of Ubu on a program when staging his drama in tandem with a play by the avant-garde poet, John Ashbery.

Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu the King [and] John Ashbery (1927–2017), The Heroes (New York: [The Living Theatre], [1952]). The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased for the Robert J. and Linda Klieger Stillman Pataphysics Collection on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2018. PML 197920.

Mary Reynolds and Marcel Duchamp

“Rabelais and Jarry are my gods,” Marcel Duchamp once stated. Jarry’s engagements with machines, science, alter egos, wordplay, and the letter r certainly resonate in Duchamp’s works. His friend Mary Reynolds (1891–1950) was one of the few Surrealist devotees of Jarry to express herself through the art of bookbinding. She created unique bindings for all of Jarry’s major works. Her first project, shown at left in the case, realized Duchamp’s design for an edition of Ubu roi. The U-shaped covers synthesize the work in one letterform—a gesture Jarry himself made in reference to the second letter r in the play’s first word, “merdre.” It also suggests a pun in English (you are Ubu).

Reynolds’s extraordinary binding design for Docteur Faustroll, shown at right, suggests an assimilation of Jarry and Duchamp. The perforated copper sheets on the covers, which allude to Faustroll’s sieve-bottomed boat, are framed like the windowpanes in versions of Duchamp’s miniature readymades. Inside the book’s covers, Reynolds chose the color green for the silk endpapers, reflecting both Ubu’s signature expletive (“By my green candle!”) and the green silk lining of Duchamp’s The Green Box (1934).

At left in case: Mary Reynolds (1891–1950) and Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), bookbinding, ca. 1934–35, goatskin, gilt, silk, and glassine, on Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Ubu roi (Paris: Librarie Charpentier et Fasquelle, 1921). The Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries. At right in case: Mary Reynolds (1891–1950), bookbinding, ca. 1940, calf and other leathers, copper, gilt, and glassine, on Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), Gestes et opinions du Docteur Faustroll, pataphysicien (Paris: Librairie Stock, 1923). The Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries.

Franciszka Themerson