Painted with Words: Vincent van Gogh's Letters to Émile Bernard

Painted with Words is a compelling look at Vincent van Gogh's correspondence to his young colleague Émile Bernard between 1887 and 1889. Van Gogh's words and sketches reveal his thoughts about art and life and communicate his groundbreaking work in Arles to his fellow painter.

Van Gogh's letters to Bernard reveal the tenor of their relationship. Van Gogh assumed the role of an older, wiser brother, offering praise or criticism of Bernard's paintings, drawings, and poems. At the same time the letters chronicle van Gogh's own struggles, as he reached his artistic maturity in isolation in Arles and St. Rémy. Throughout the letters are no less than twelve sketches by van Gogh meant to provide Bernard with an idea of his work in progress, including studies related to the paintings The Langlois Bridge, Houses at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, Boats on the beach at Saintes-Maries, The Sower, and View of Arles at Sunset.

The translations used in this presentation are from the catalogue for the exhibition: Vincent van Gogh Painted with Words, The Letters to Émile Bernard and are reproduced by kind permission of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Hear our Director Colin B. Bailey explain why these are some of the most moving and precious objects in our collection:

Major support for Painted with Words: Vincent van Gogh's Letters to Émile Bernard and its accompanying catalogue was provided by the International Music and Art Foundation. Generous support was also provided by the Robert Lehman Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Thumbnails

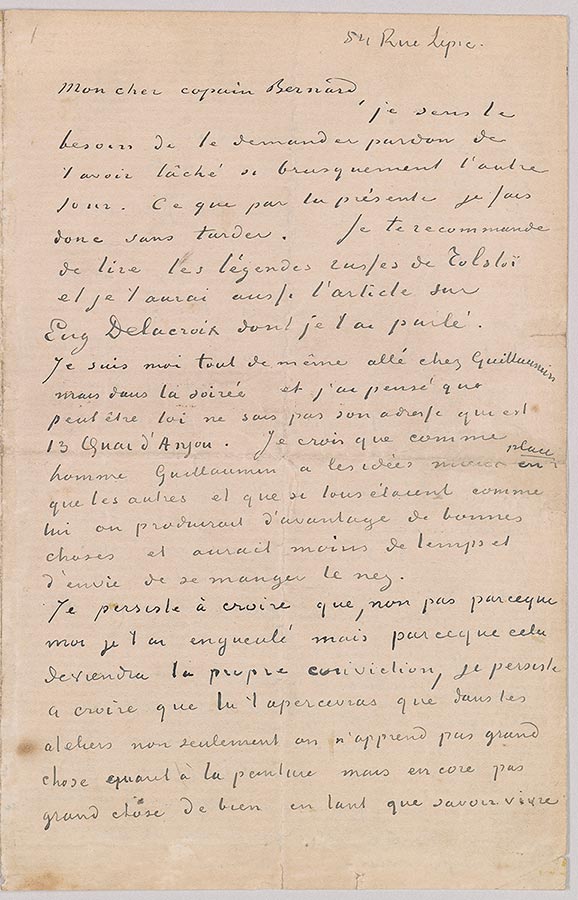

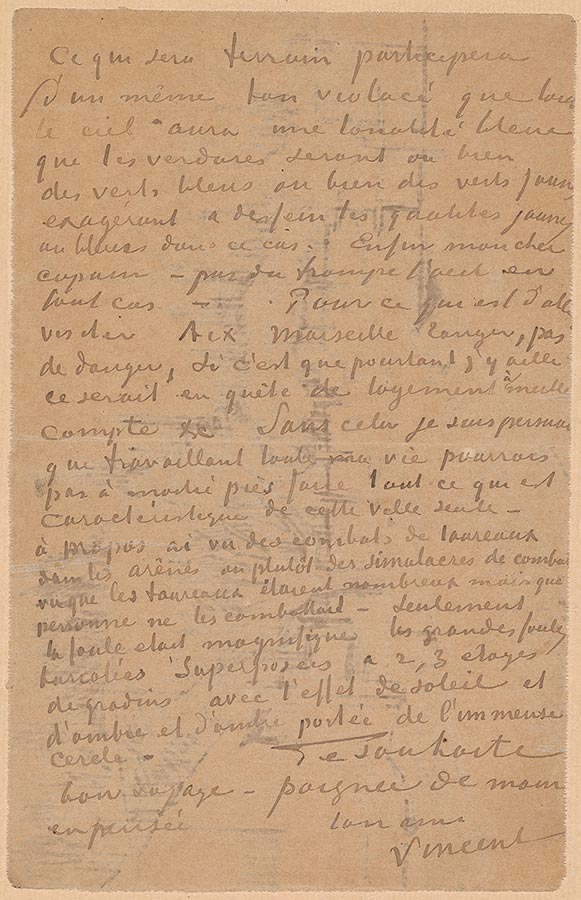

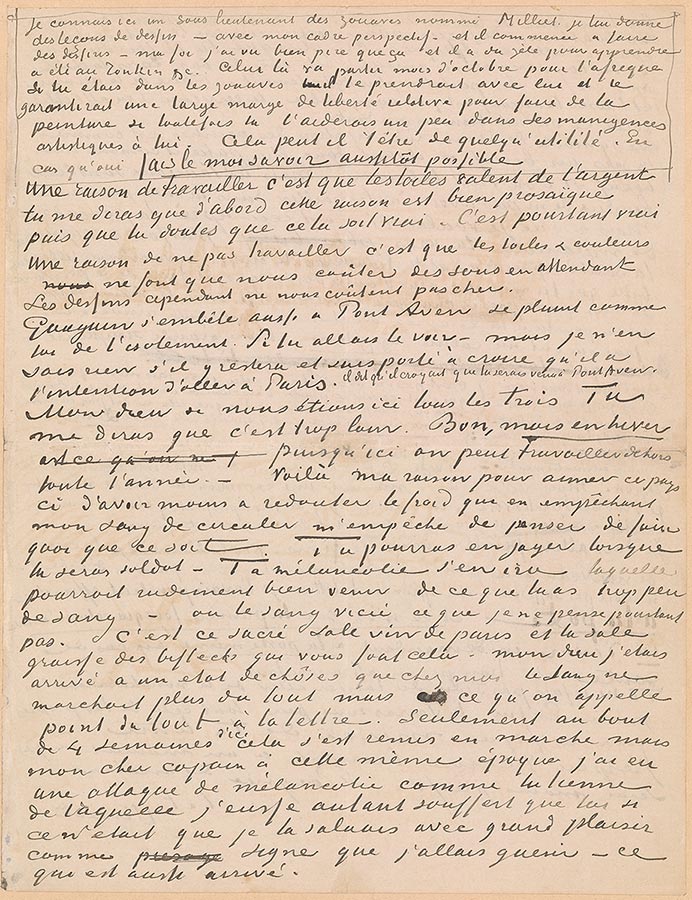

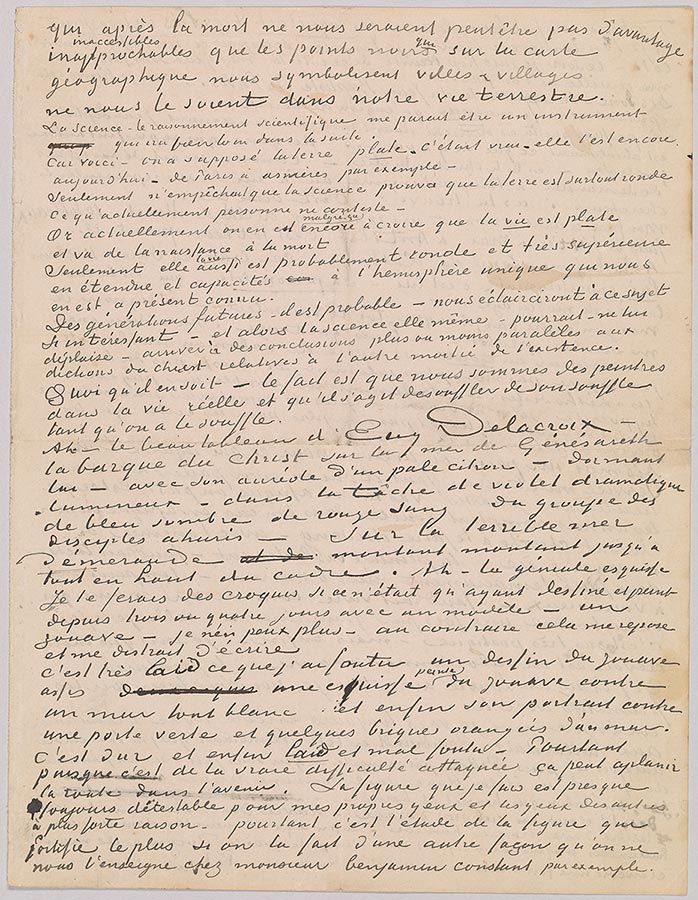

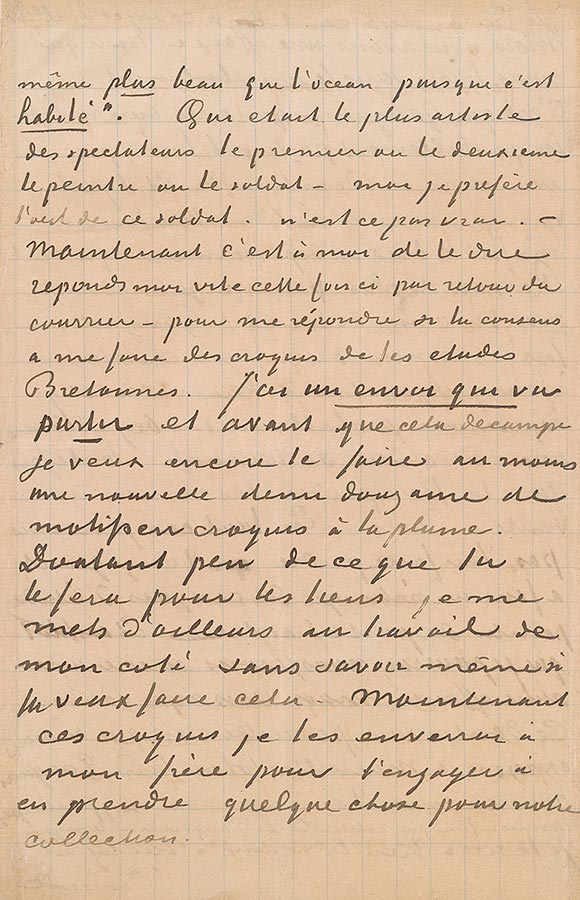

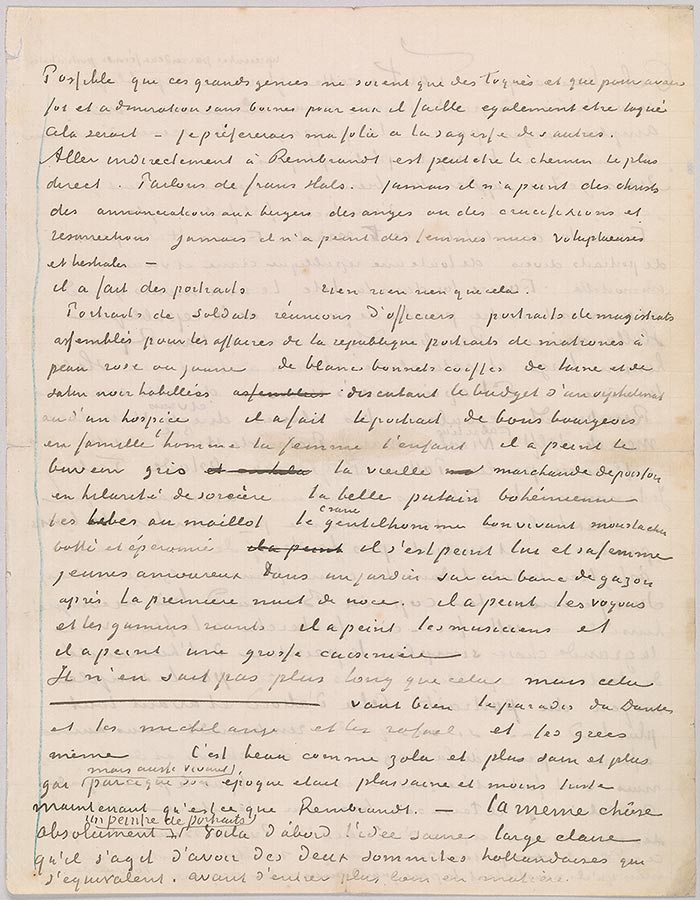

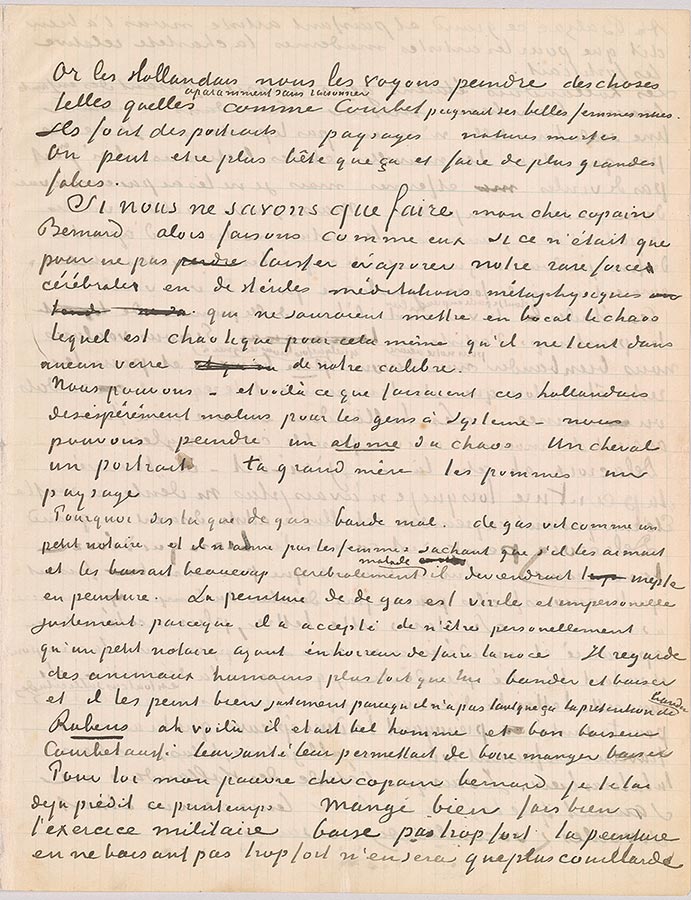

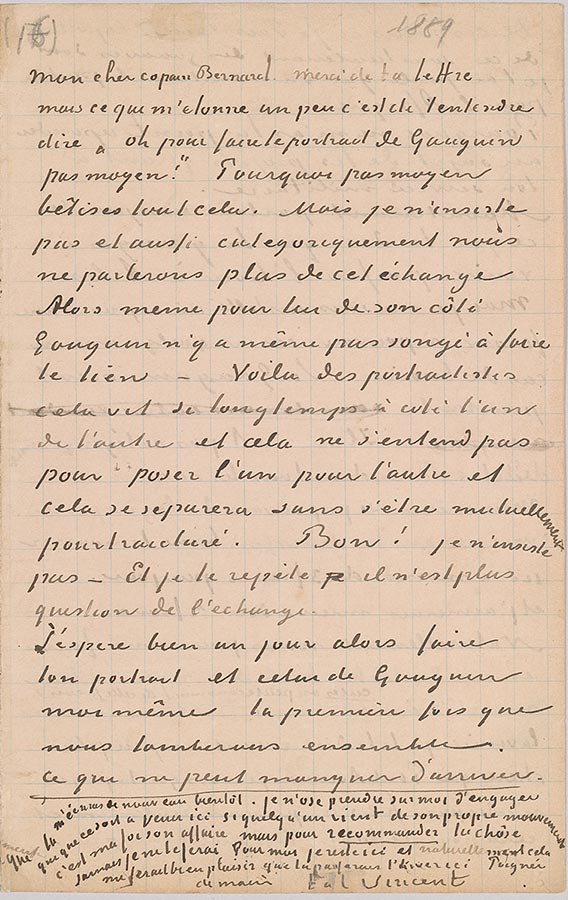

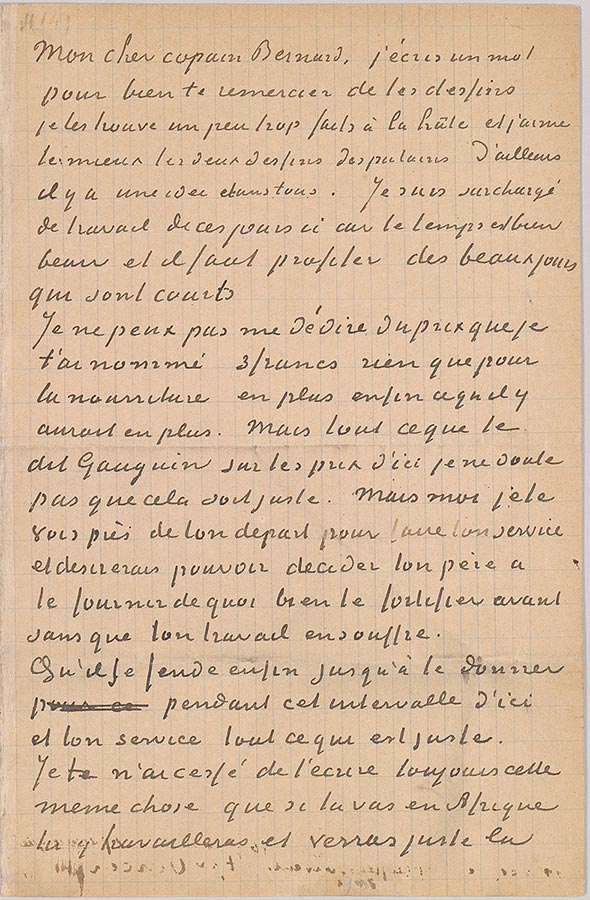

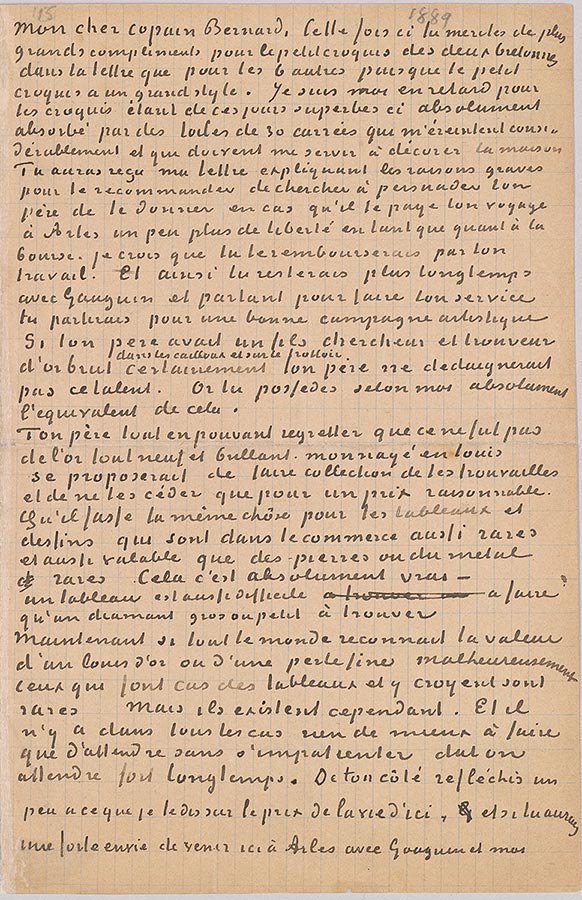

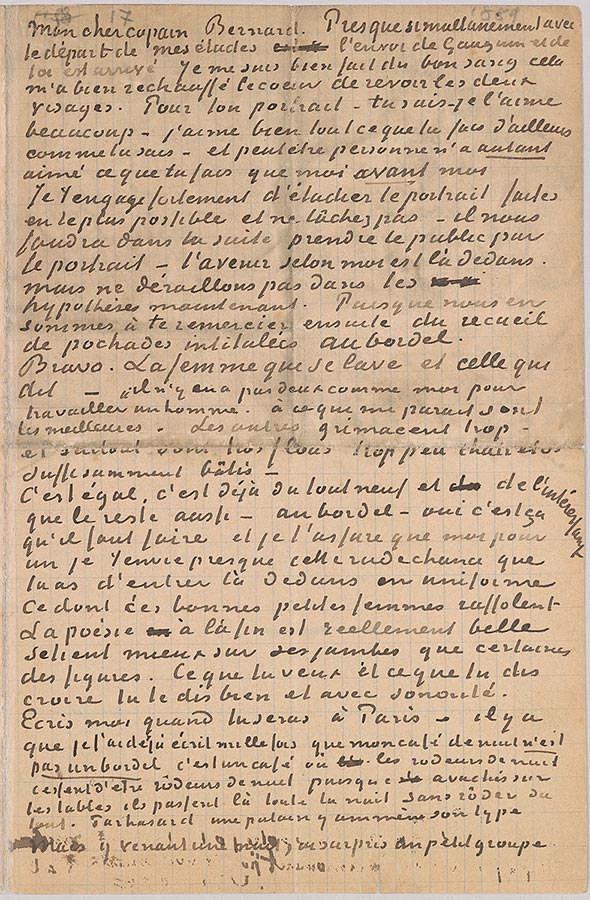

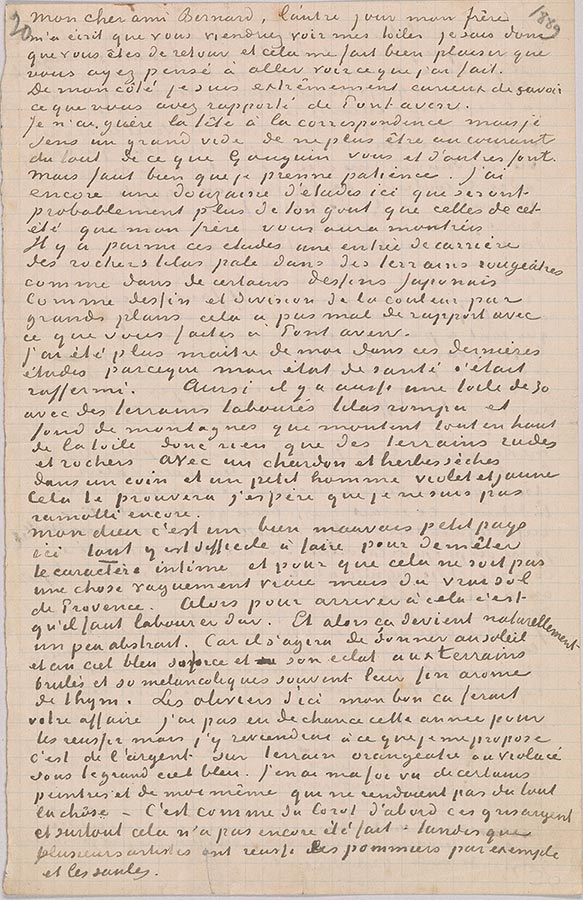

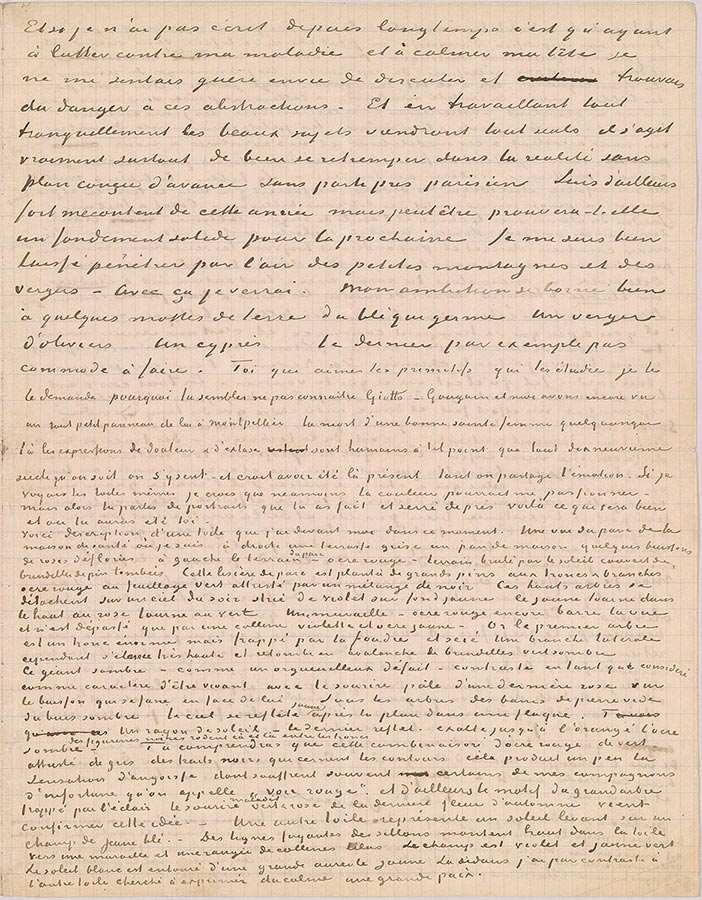

Letter 1, page 1

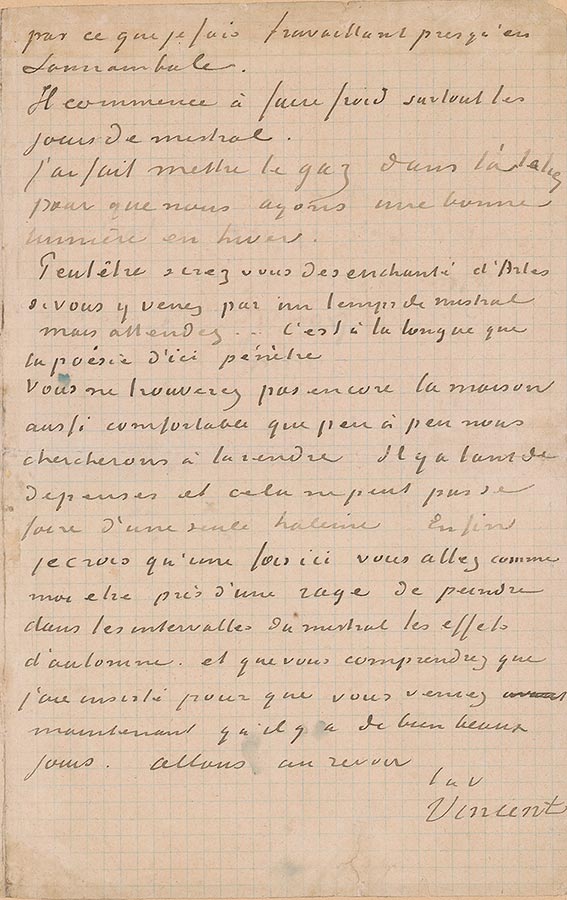

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Paris, ca. December 1887, Letter 1, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

54 rue Lepic.

My dear old Bernard,

I feel the need to beg your pardon for leaving you so abruptly the other day. Which I therefore do

herewith, without delay. I recommend that you read Tolstoy's Les Légendes Russes, and I'll also let

you have the article on E. Delacroix that I've spoken to you about.

I, for my part, did go to Guillaumin's anyway, but in the evening, and I thought that perhaps

you didn't know his address, which is 13 quai d'Anjou. I believe that, as a man, Guillaumin has

sounder ideas than the others, and that if we were all like him we'd produce more good things and

would have less time and inclination to be at each other's throats.

I persist in believing that—not because I gave you a rocket but because it will become your

own conviction—I persist in believing that you'll realize that in the studios not only does one not

learn very much as far as painting goes, but not much that's good in terms of savoir vivre, either.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

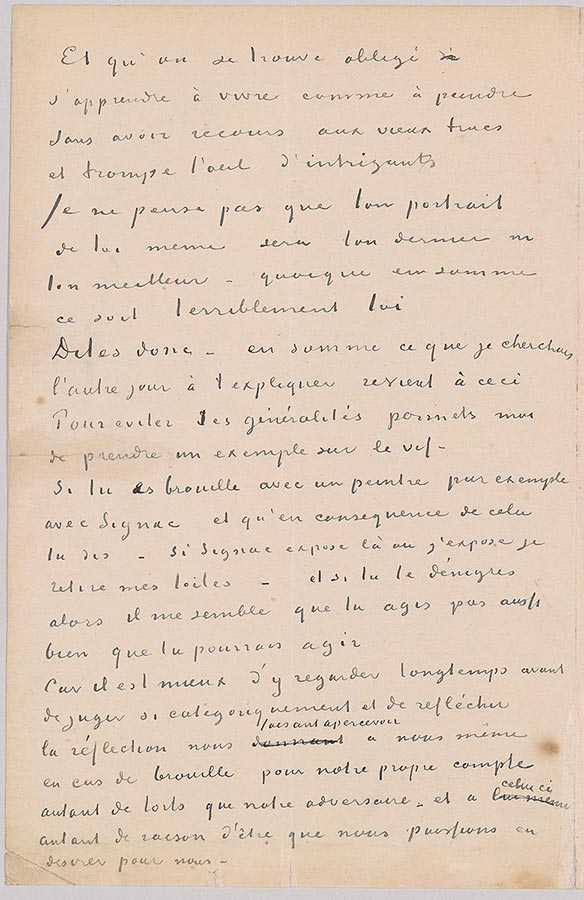

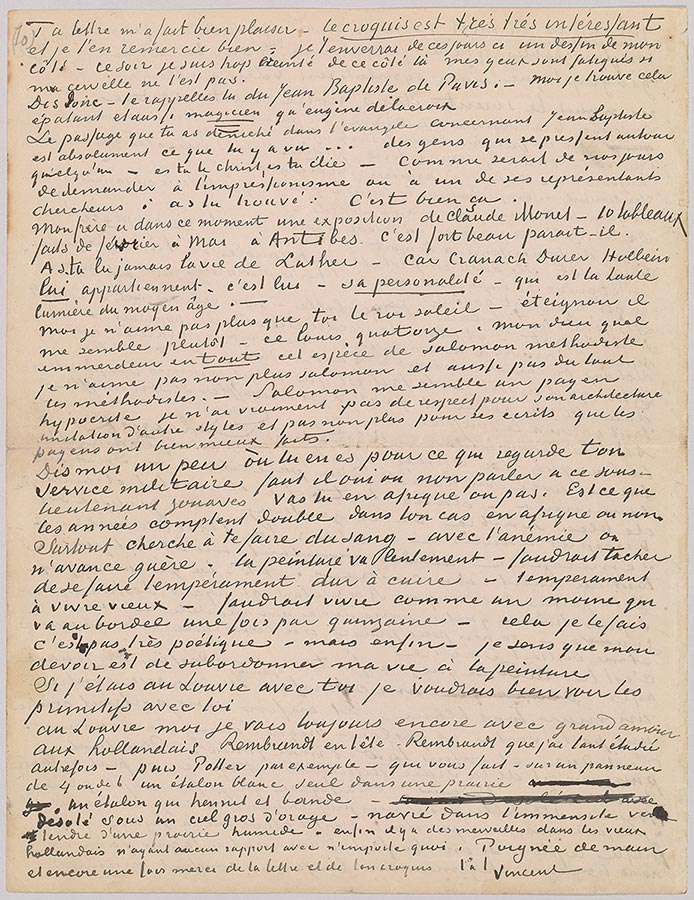

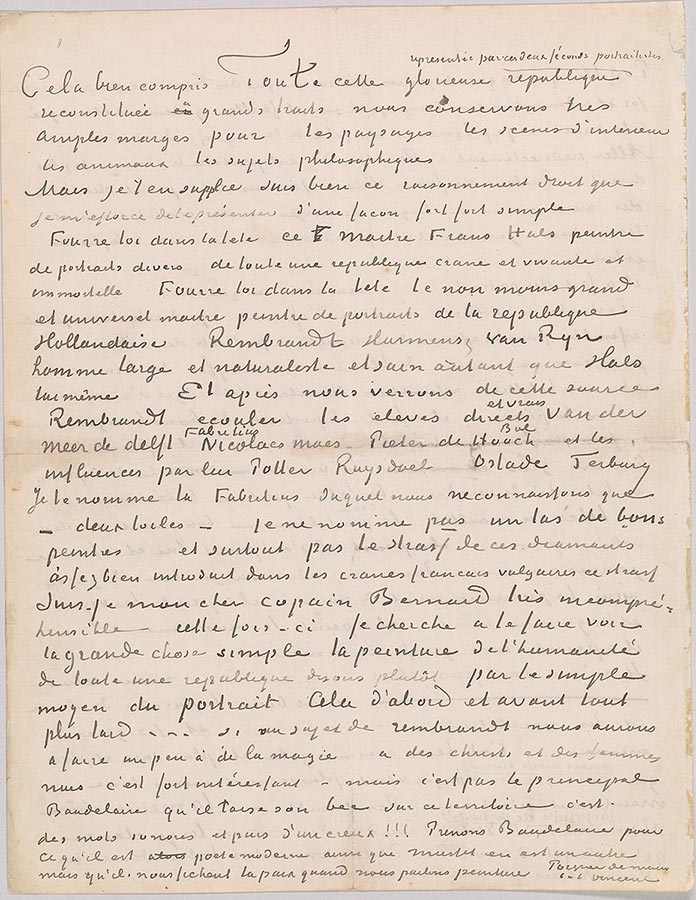

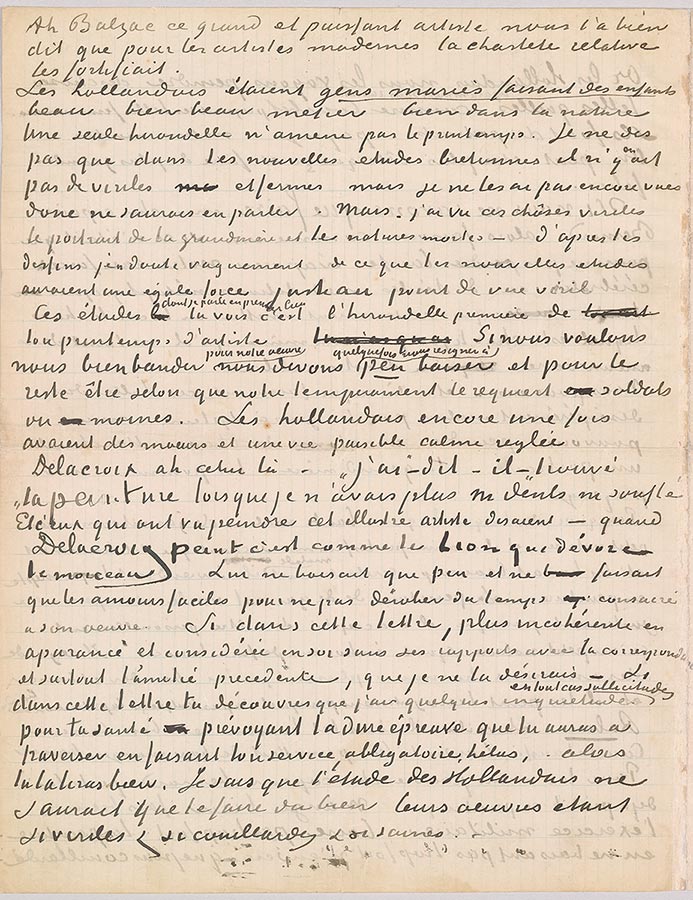

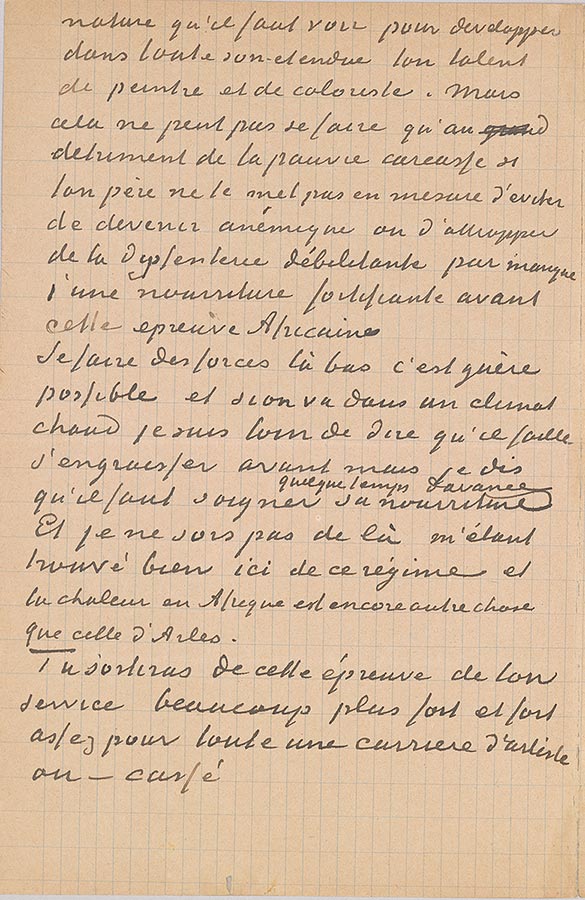

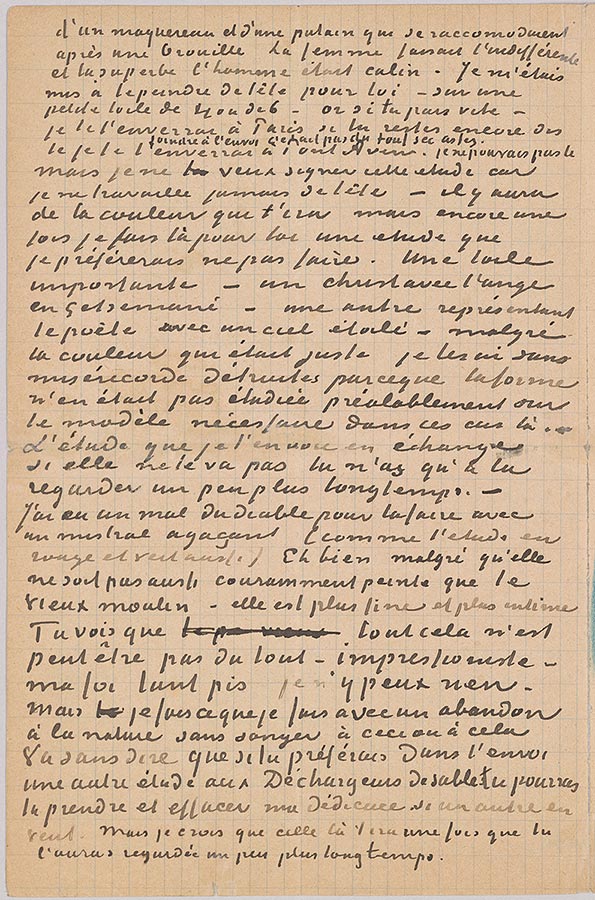

Letter 1, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard,Paris, ca. December 1887, Letter 1, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

And that one finds oneself obliged to learn to live, as one does to paint, without resorting to the old

tricks and trompe l'oeil of schemers.

I don't think your portrait of yourself will be your last, or your best—although all in all it is

frightfully you.

Look here—briefly, what I was trying to explain to you the other day comes down to this.

In order to avoid generalities, let me take an example from life.

If you've fallen out with a painter, with Signac, for example, and if as a result you say:

I'll withdraw my canvases if Signac exhibits where I exhibit—and if you run him down, then it

seems to me that you are not behaving as well as you could.

Because it's better to take a long look at it before judging so categorically and to reflect,

reflection making us see in ourselves, when there's a falling out, as many faults on our own side

as in our adversary, and in him as many justifications as we might

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

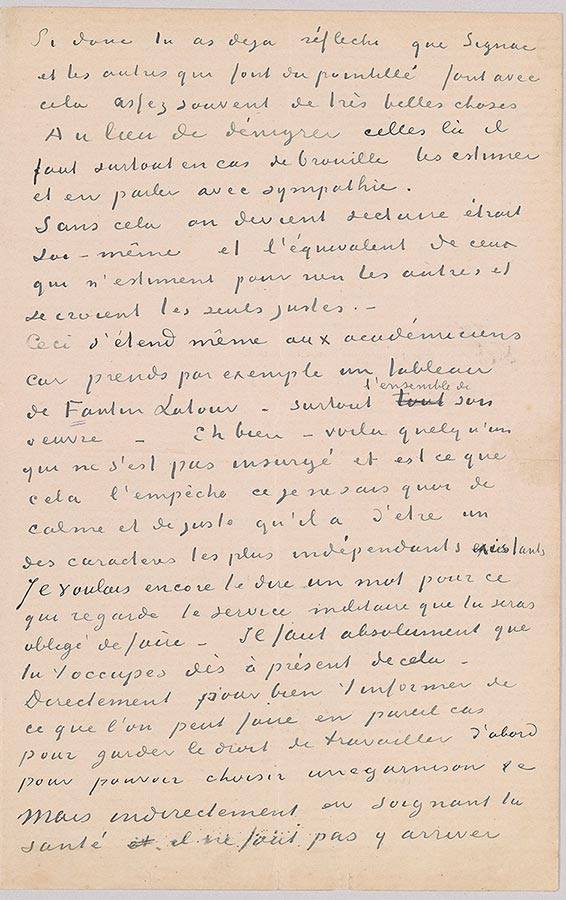

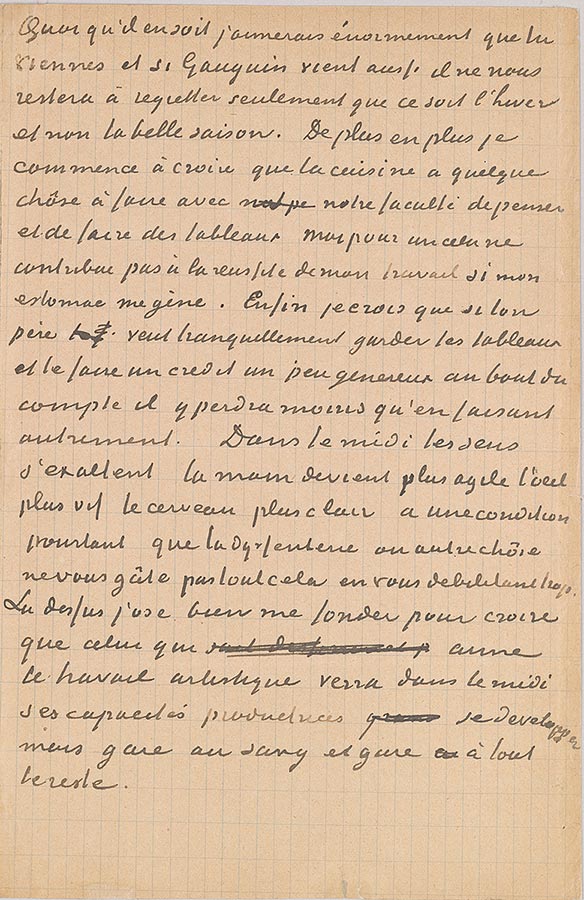

Letter 1, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard,Paris, ca. December 1887, Letter 1, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

desire for ourselves.

If, therefore, you have already considered that Signac and the others who are doing pointillism

often make very beautiful things with it—

Instead of running those things down, one should respect them and speak of them sympathetically,

especially when there's a falling out.

Otherwise one becomes a narrow sectarian oneself and the equivalent of those who think

nothing of others and believe themselves to be the only righteous ones.

This extends even to the academicians, because take, for example, a painting by Fantin-Latour

—and above all his entire oeuvre. Well then—there's someone who hasn't rebelled, and does that

prevent him, that indefinable calm and righteousness that he has, being one of the most independent

characters in existence?

I also wanted to say a word to you about the military service that you will be required to do.

You must absolutely see to that now.

Directly, in order to inform yourself properly about what one can do in such an event; first to

retain the right to work, to be able to choose a garrison, etc. But indirectly, by taking care of your

health. You mustn't arrive there

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

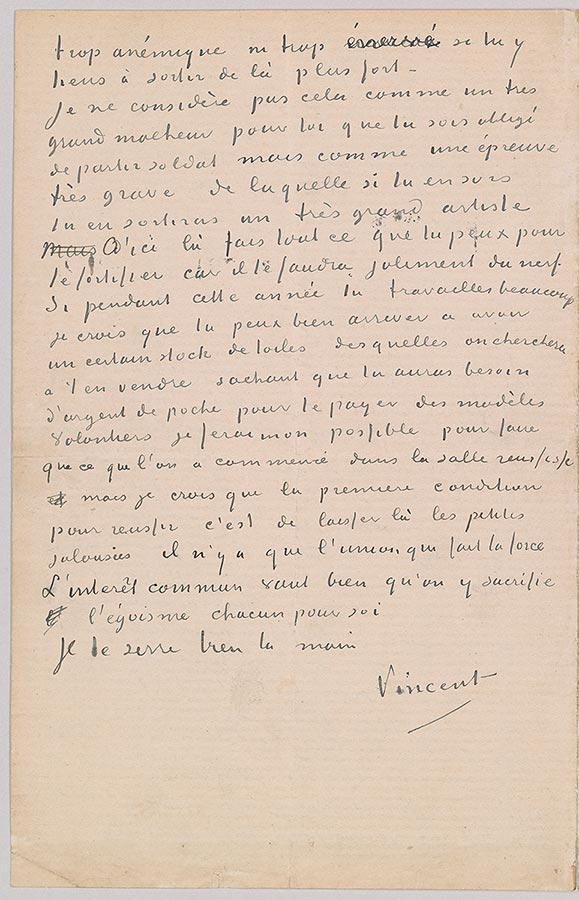

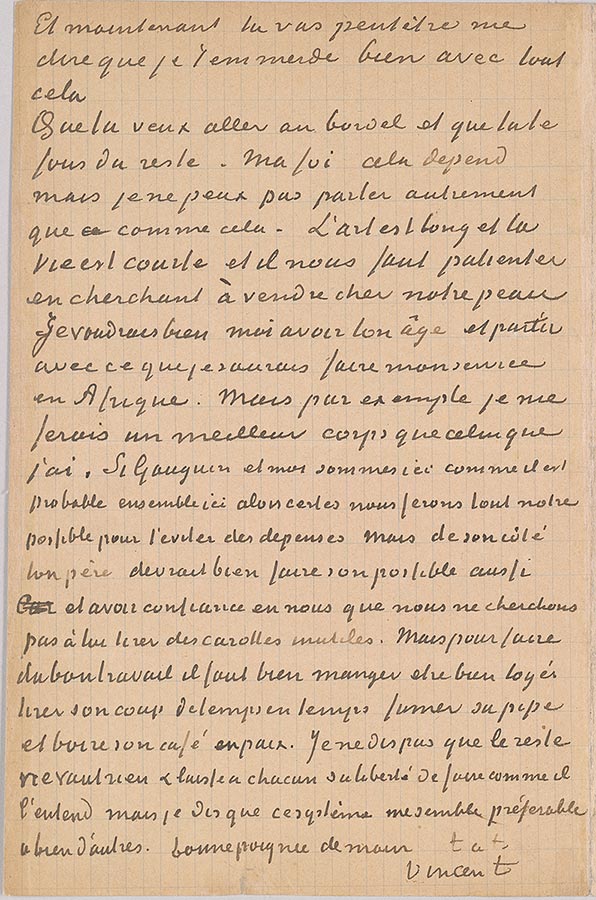

Letter 1, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard,Paris, ca. December 1887, Letter 1, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

too anemic or too agitated if you want to emerge from it stronger.

I do not see it as a very great misfortune for you that you have to join the army but as a very

grave ordeal, from which, if you emerge from it, you'll emerge a very great artist. Until then, do all

you can to build yourself up, because you'll need quite a bit of spirit. If you work hard that year, I

believe that you may well succeed in having a fair stock of canvases, some of which we'll try to sell

for you, knowing that you'll need pocket money to pay for models.

I 'll gladly do all I can to make a success of what was started in the dining room, but I believe

that the first condition for success is to put aside petty jealousies; it's only unity that makes

strength. It's well worth sacrificing selfishness, the "each man for himself," in the common interest.

I shake your hand firmly.

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

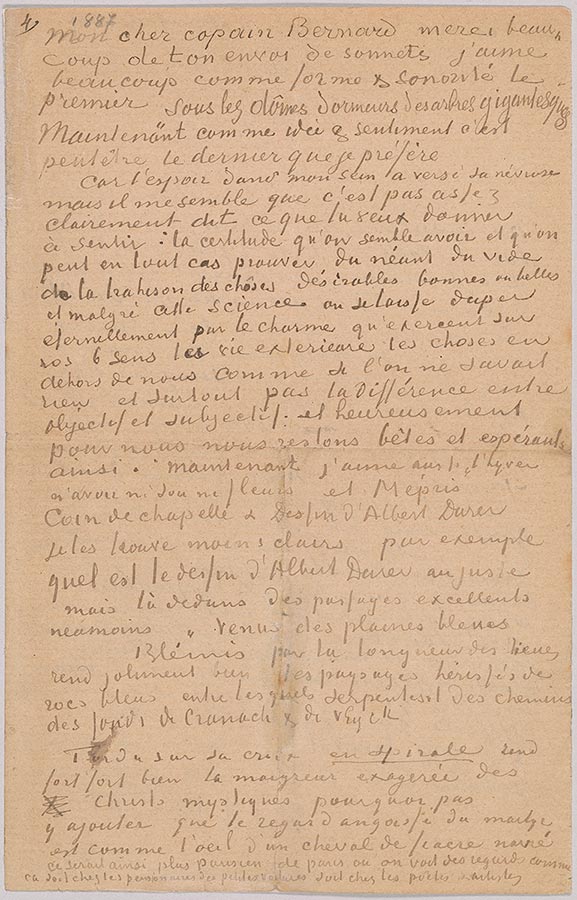

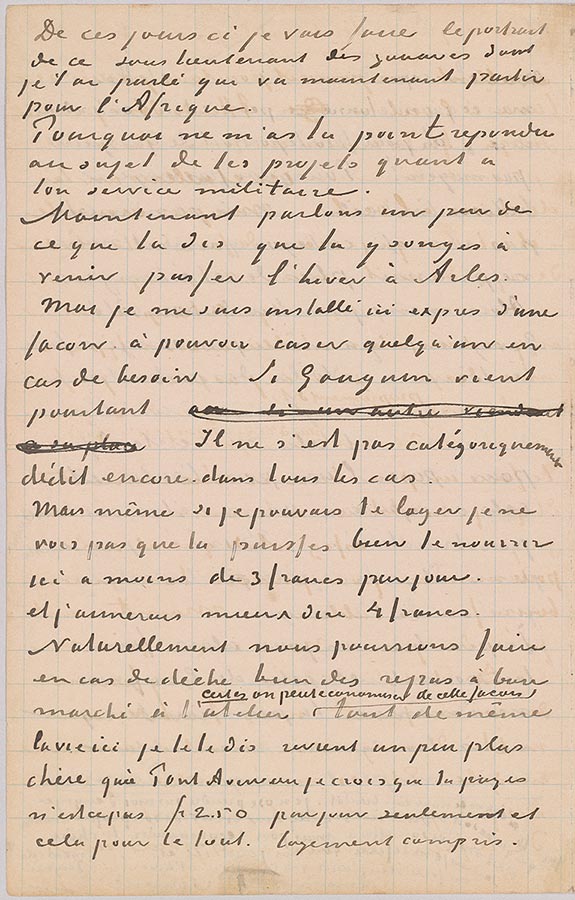

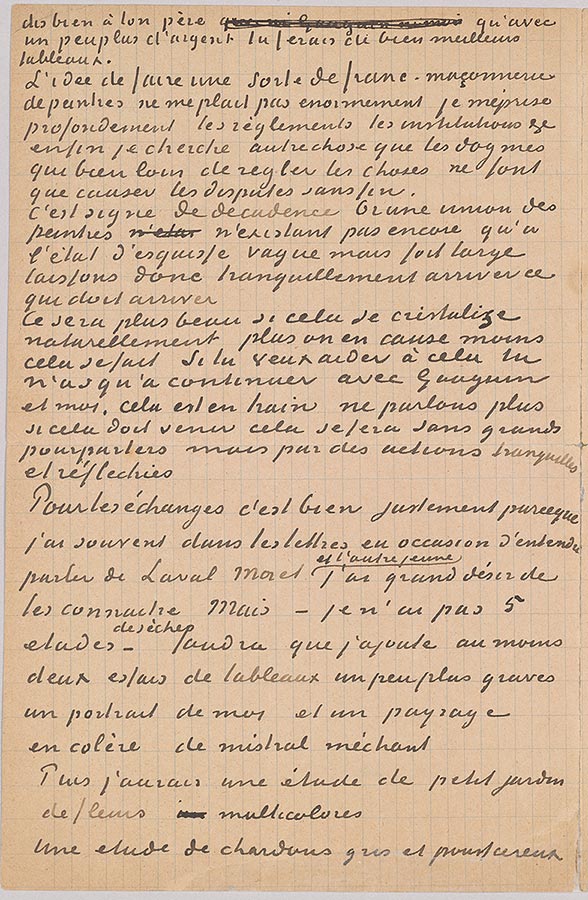

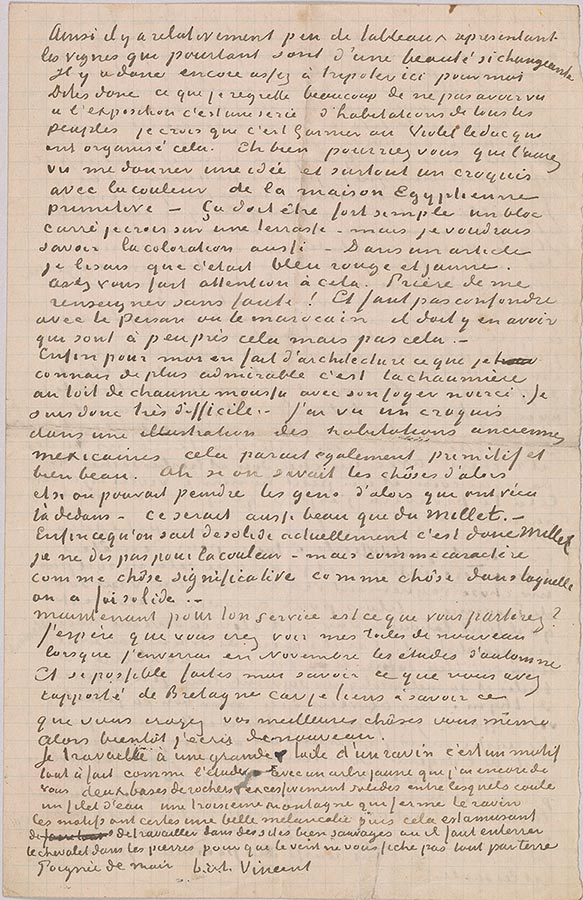

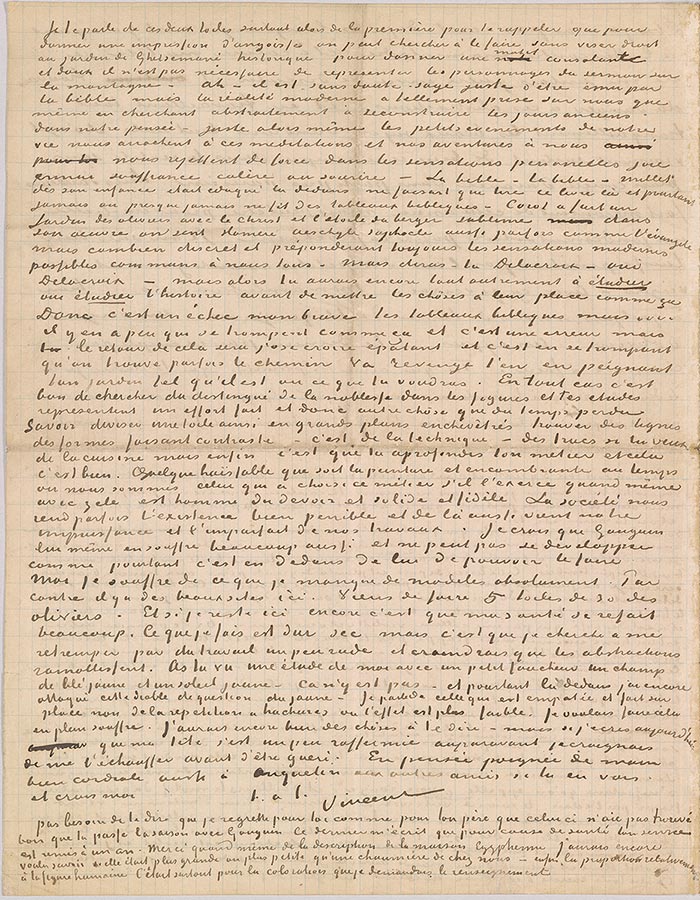

Letter 2, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 18 March 1888, Letter 2, page 1

Drawbridge with walking couple

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear Bernard,

Having promised to write to you, I want to begin by telling you that this part of the world seems to

me as beautiful as Japan for the limpidity of the atmosphere and the gay color effects. The stretches

of water make patches of a beautiful emerald and a rich blue in the landscapes, as we see it in the

Japanese prints. Pale orange sunsets making the fields look blue—glorious yellow suns. So far,

however, I've hardly seen this part of the world in its usual summer splendor. The women's costume

is pretty, and especially on the boulevard on Sunday you see some very naive and well-chosen

arrangements of color. And that, too, will doubtless get even livelier in summer.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 2, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 18 March 1888, Letter 2, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

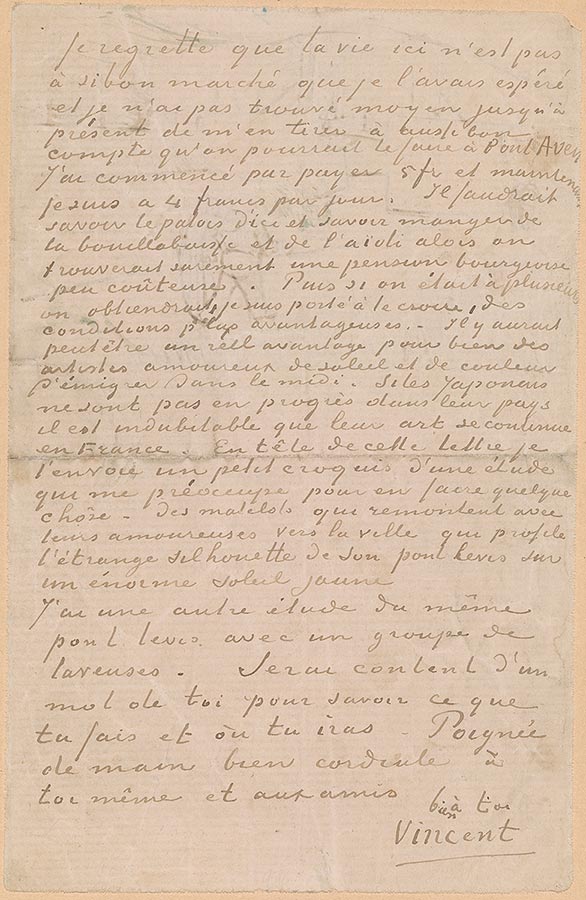

I regret that living here isn't as cheap as I'd hoped, and until now I haven't found a way of getting

by as easily as one could in Pont-Aven. I started out paying 5 francs and now I'm on 4 francs

a day. One would need to know the local patois, and know how to eat bouillabaisse and aioli, then

one would surely find an inexpensive family boardinghouse. Then if there were several of us, I'm

inclined to believe we would get more favorable terms. Perhaps there would be a real advantage in

emigrating to the south for many artists in love with sunshine and color. The Japanese may not be

making progress in their country, but there is no doubt that their art is being carried on in France.

At the top of this letter I am sending you a little sketch of a study that is preoccupying me as to

how to make something of it—sailors coming back with their sweethearts toward the town, which

projects the strange silhouette of its drawbridge against a huge yellow sun.

I have another study of the same drawbridge with a group of washerwomen. Shall be happy to

have a line from you to know what you're doing and where you're going to go. A very warm handshake

to you and the friends.

Yours,

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 3, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 12 April 1888, Letter 3, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

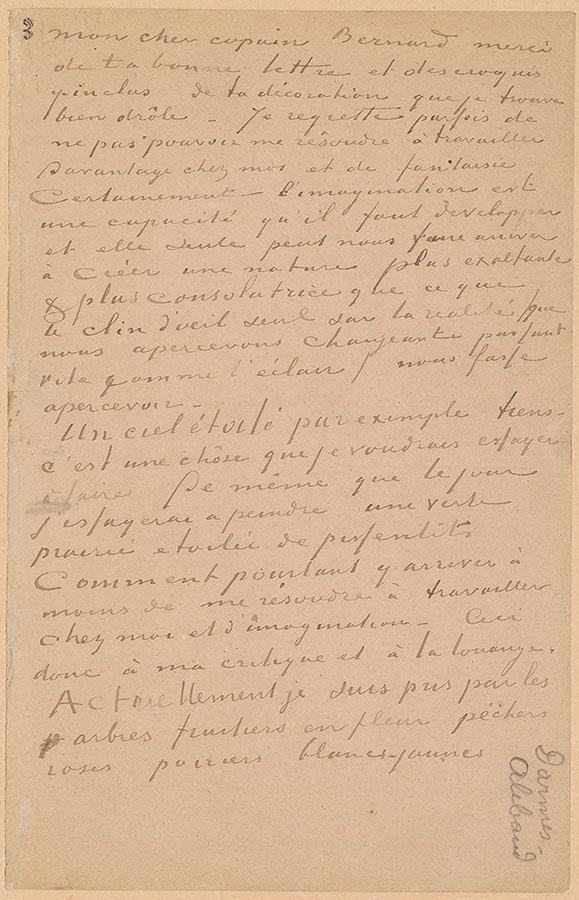

My dear old Bernard,

Thanks for your kind letter and the sketch of your decoration included with it, which I find really

amusing. I sometimes regret that I can't decide to work more at home and from the imagination.

Certainly—imagination is a capacity that must be developed, and only that enables us to create a

more exalting and consoling nature than what just a glance at reality (which we perceive changing,

passing quickly like lightning) allows us to perceive.

A starry sky, for example, well—it's a thing that I should like to try to do, just as in the daytime

I'll try to paint a green meadow studded with dandelions.

But how to arrive at that unless I decide to work at home and from the imagination? This,

then, to criticize myself and to praise you.

At present I am busy with the fruit trees in blossom: pink peach trees, yellow-white pear trees.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

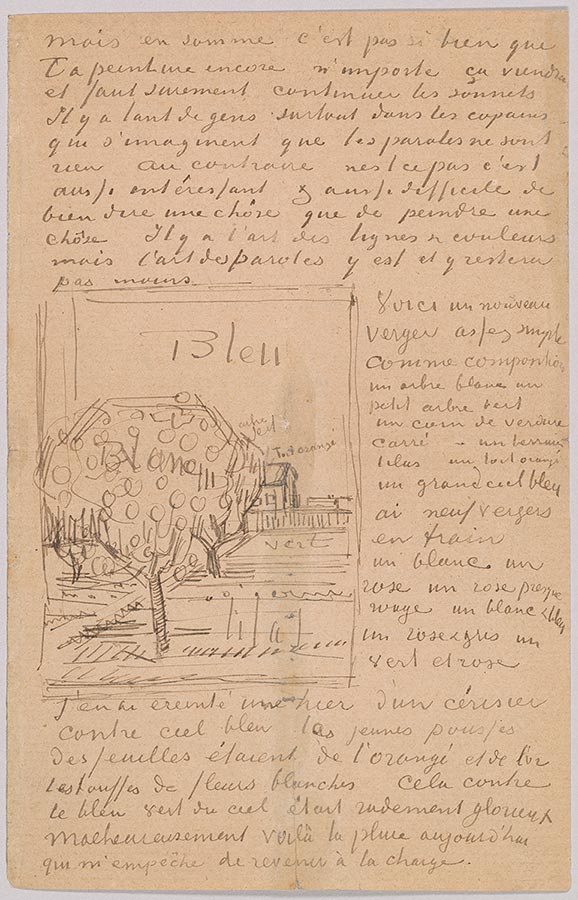

Letter 3, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 12 April 1888, Letter 3, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

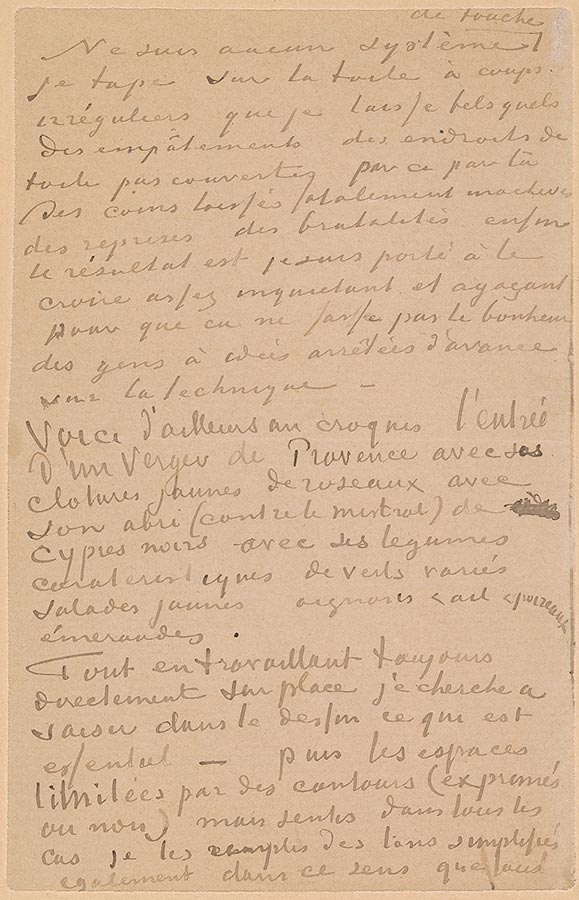

I follow no system of brushwork at all, I hit the canvas with irregular strokes, which I leave as

they are, impastos, uncovered spots of canvas—corners here and there left inevitably unfinished—

reworkings, roughnesses; well, I'm inclined to think that the result is sufficiently worrying and

annoying not to please people with preconceived ideas about technique.

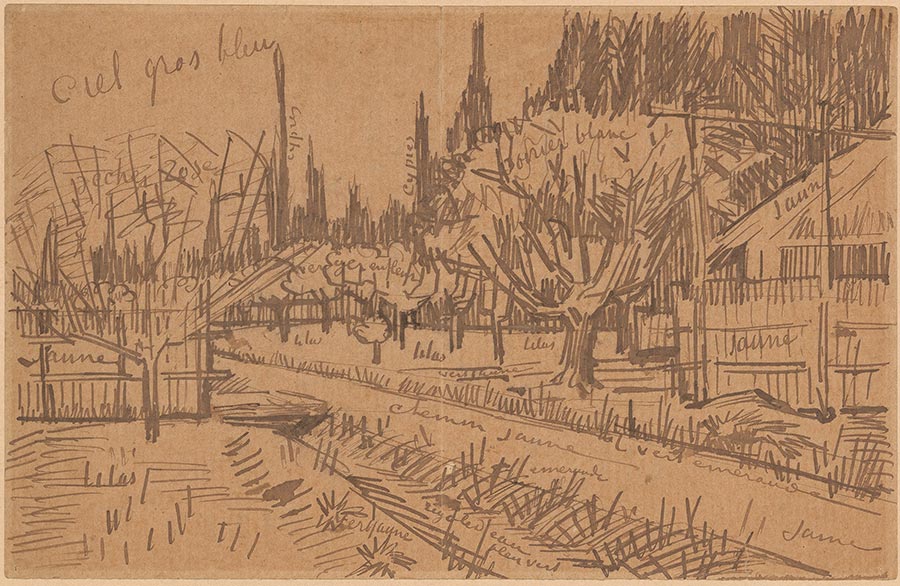

Here's a sketch, by the way, the entrance to a Provençal orchard with its yellow reed fences,

with its shelter (against the mistral), black cypresses, with its typical vegetables of various greens,

yellow lettuces, onions and garlic and emerald leeks.

While always working directly on the spot, I try to capture the essence in the drawing—then

I fill the spaces demarcated by the outlines (expressed or not) but felt in every case, likewise with

simplified tints, in the sense that everything

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

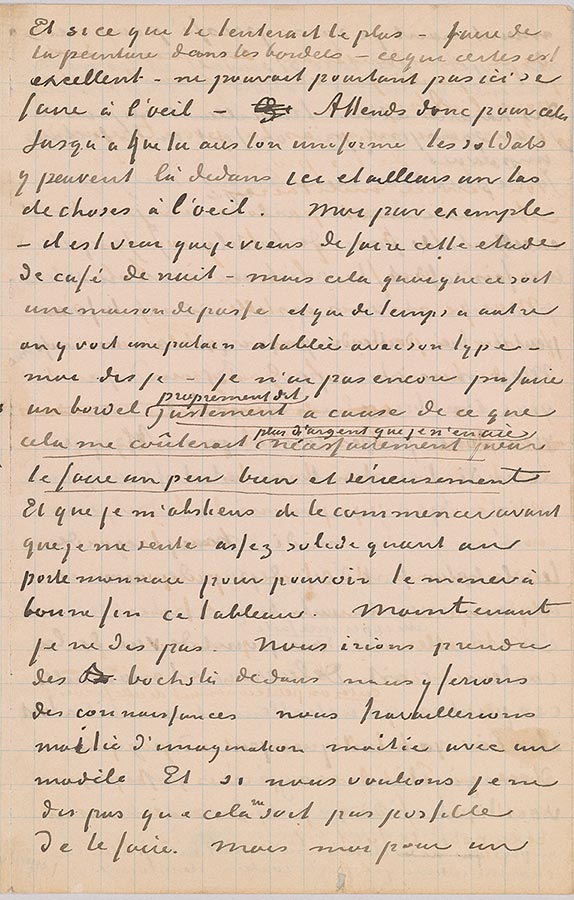

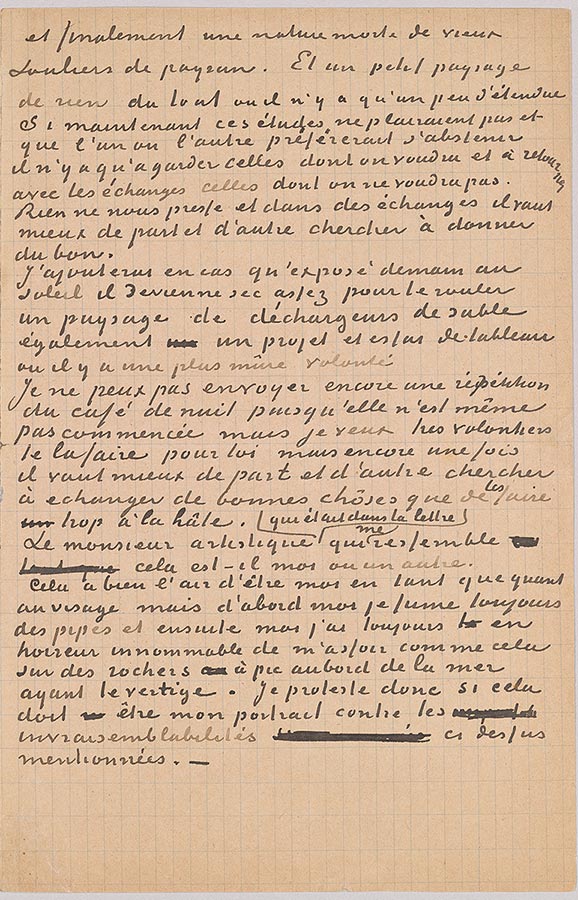

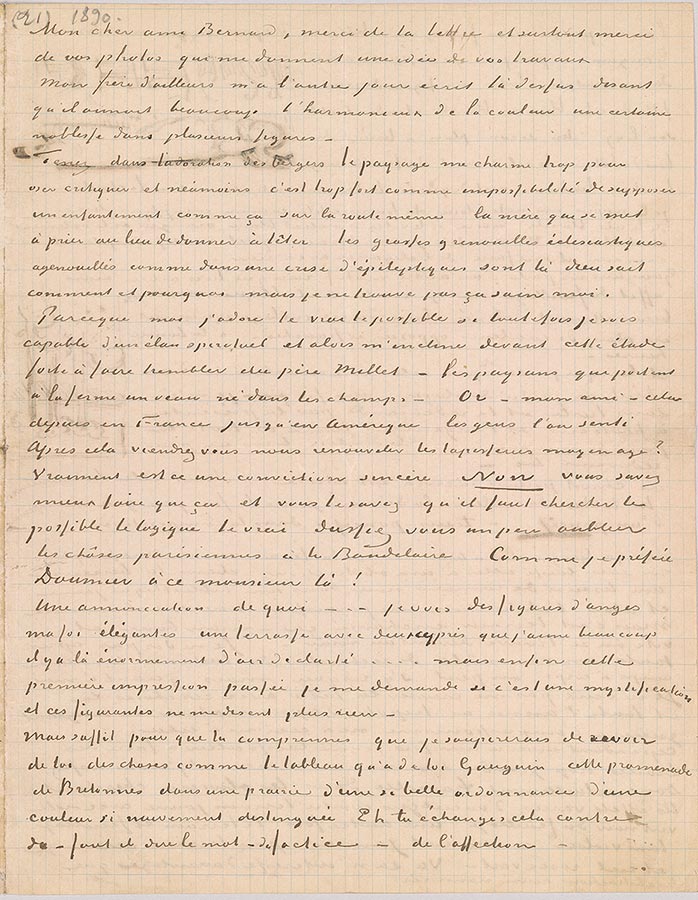

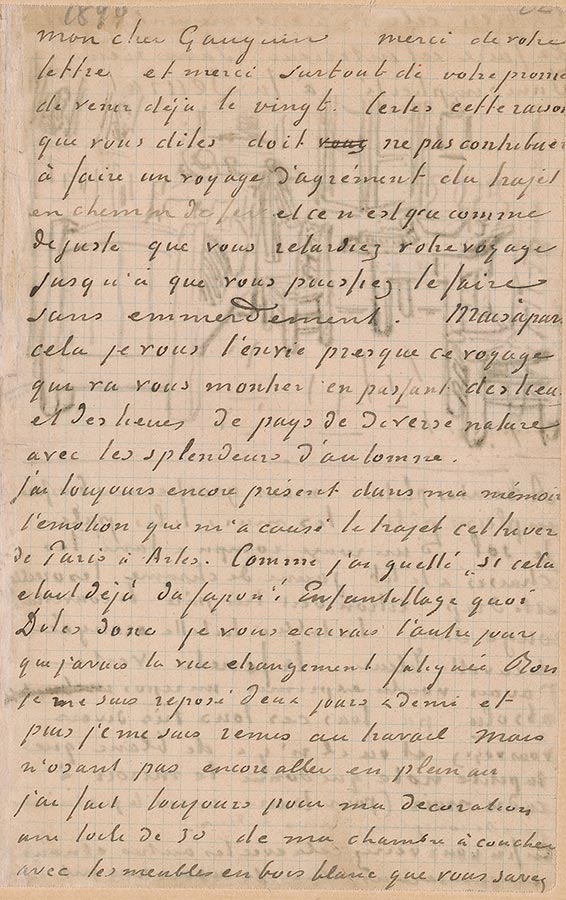

Letter 3, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 12 April 1888, Letter 3, page 3

Orchard surrounded by cypresses

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

The first paragraph of this letter addresses a central issue of debate between van Gogh, Bernard, and Gauguin. Bernard and Gauguin favored working from the imagination, producing what they called abstractions, while van Gogh felt a pressing need to work directly from nature, which presented its own obstacles. Van Gogh mused about painting outdoors after sundown, "A starry sky, for example, well—it's a thing that I should like to try to do. . . . But how to arrive at that unless I decide to work at home and from the imagination?" Seven months later van Gogh depicted his first evening sky, and the following year he produced his nocturnal masterpiece, Starry Night, now in the Museum of Modern Art.

In order to communicate essential information about his use of color, van Gogh described at length the pigments he used and their intended effect. Here he wrote of his recent paintings of fruit trees in blossom, proud of his unconventional brushwork—the impasto for which he is famed—and idiosyncratic use of color. Satisfied with his departure from convention, van Gogh assumed that "the result is sufficiently worrying and annoying not to please people with preconceived ideas about technique." He then quarter turned the sheet and quickly drafted a sketch after his first version of a painting of a Provençal orchard.

Letter 3, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 12 April 1888, Letter 3, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

that will be earth will share the same purplish

tint, that the whole sky will have a blue tonality, that the greenery will either be blue greens or

yellow greens, deliberately exaggerating the yellow or blue values in that case. Anyway, my dear

pal, no trompe l'oeil in any case. As for going to visit Aix, Marseille, Tangier, no fear; if I were to go

there, however, it would be in search of cheaper lodgings, etc. Otherwise, I'm convinced that if I

worked my whole life, couldn't do as much as half of all that is characteristic of this town alone.

By the way, have seen bullfights in the arenas, or rather, simulated fights, seeing that the bulls

were numerous but nobody was fighting them. But the crowd was magnificent, great multicolored

crowds. One on top of the other on two, three tiers, with the effect of sun and shade and the

shadow of the immense circle. Wish you bon voyage—handshake in thought, your friend

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 4, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 19 April 1888, Letter 4, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear old Bernard,

Many thanks for sending your sonnets. For form and sonority I very much like the first one,

"Under the sleeping canopies of the gigantic trees." Now for idea and sentiment it's perhaps the

last one that I prefer: "For hope has poured its nervousness into my breast," but it seems to me that

what you want to evoke isn't stated clearly enough: the certainty that we seem to have and which

anyway we can prove, of nothingness, of emptiness, of the treachery of desirable, good, or beautiful

things, and despite this knowledge we forever allow ourselves to be deceived by the spell that

external life, things outside ourselves, cast over our six senses, as though we knew nothing, and

especially not the difference between objective and subjective. And fortunately for us, in that way

we remain ignorant and hopeful. Now I also like "In winter, have neither a sou nor a flower," and

"Contempt." "Corner of a chapel" and "Drawing by Albrecht Dürer" I find less clear. For example,

precisely which drawing by Albrecht Dürer is it? But excellent passages in it nevertheless. "Having

come from the blue plains, Made pale by the long miles" is a jolly good rendering of the landscapes

bristling with blue rocks between which the roads wind in the backgrounds of Cranach and Van Eyck.

Twisted on his cross in a spiral is a very, very good rendering of the exaggerated thinness of the

mystical Christs; why not add to it that the anguished expression of the martyr is like the eye of

a brokenhearted cab horse? That way it would be more utterly Parisian, where you see looks like

that, either in the drivers of the little carriages or in poets and artists.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 4, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 19 April 1888, Letter 4, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

But all in all it's not as good

as your painting yet. Never mind. It'll come, and you must certainly continue doing sonnets.

There are so many people, especially among our pals, who imagine that words are nothing.

On the contrary, don't you think, it's as interesting and as difficult to say a thing well as to paint a

thing. There's the art of lines and colors, but there's the art of words that will last just the same.

Here's a new orchard, quite simple in composition: a white tree, a small green tree, a square

corner of greenery—a lilac field, an orange roof, a big blue sky. Have nine orchards in progress; one

white, one pink, one almost red pink, one white and blue, one pink and gray, one green and pink.

I worked one to death yesterday, of a cherry tree against blue sky, the young shoots of the

leaves were orange and gold, the clusters of flowers white. That, against the blue green of the sky,

was darned glorious. Unfortunately there's rain today, which prevents me going back on the attack.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

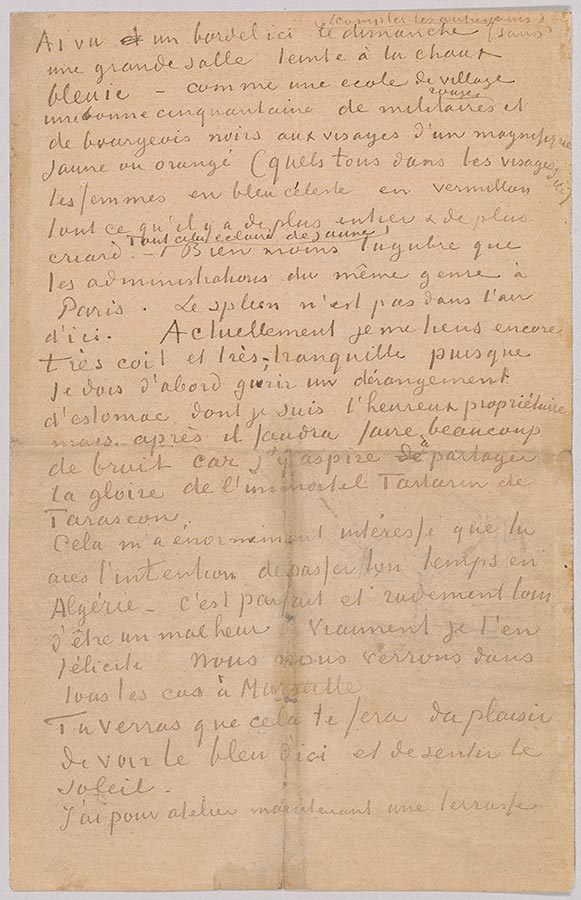

Letter 4, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 19 April 1888, Letter 4, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Saw a brothel here on Sunday (not to mention the other days), a large room tinged with a bluish

limewash—like a village school—a good fifty or so red soldiers and black civilians, with faces

of a magnificent yellow or orange (what tones in the faces down here), the women in sky blue, in

vermilion, everything that's of the purest and gaudiest. All of it in yellow light. Far less gloomy

than the establishments of the same kind in Paris. Spleen is not in the air down here. At present I'm

still keeping very quiet and very calm, because first I have to get over a stomach ailment of which

I am the happy owner, but afterwards I'll have to make a lot of noise, because I aspire to share the

renown of the immortal Tartarin de Tarascon.

It interested me enormously that you intend spending your time in Algeria. That's perfect and

a hell of a long way from being a misfortune. Truly, I congratulate you on it. We'll see each other in

Marseille in any case.

You'll find that you'll enjoy seeing the blue down here and feeling the sun.

I now have a terrace for a studio.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

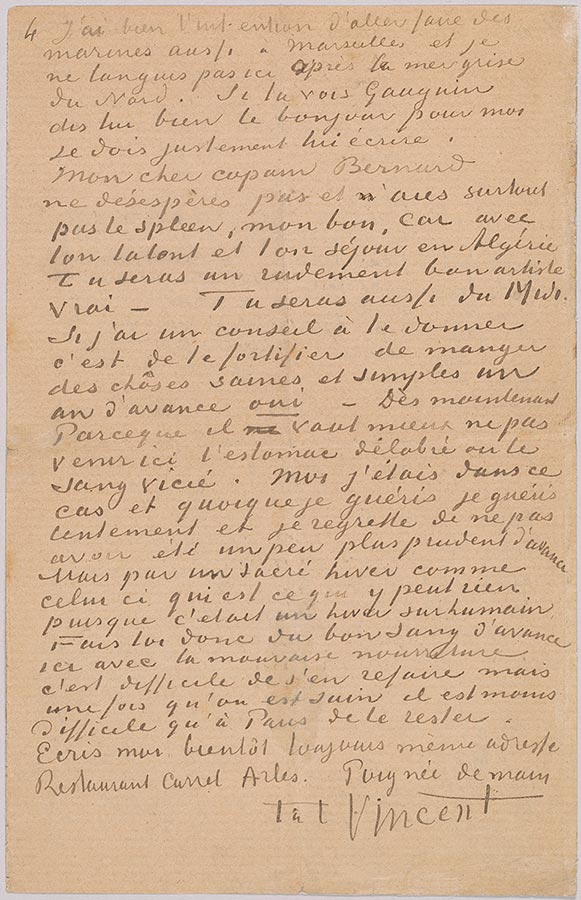

Letter 4, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 19 April 1888, Letter 4, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

(Continued from page 3)

I really intend to go and do seascapes, too, in Marseille, and I don't pine here for the gray sea

of the north. If you see Gauguin, greet him warmly for me; I must write to him in a moment.

My dear old Bernard, don't despair and above all, don't be downhearted, my good fellow,

because with your talent and your stay in Algeria, you'll be a hell of a good artist. True—you'll be

a southerner, too. If I have a piece of advice to give you, it's to build yourself up by eating healthy

and simple things for a year beforehand, yes. Starting now. Because it's better not to come here with

a ruined stomach or spoiled blood. That was the case with me, and although I'm recovering, I'm

recovering slowly, and I regret not having been a little more prudent beforehand. But who can do

anything in a bloody winter like this one, because it was a preternatural winter. So see that your

blood's good beforehand; with the bad food here it's difficult to regain that, but once you're

healthy it's less difficult to stay that way than in Paris.

Write to me soon, still same address, Restaurant Carrel, Arles. Handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

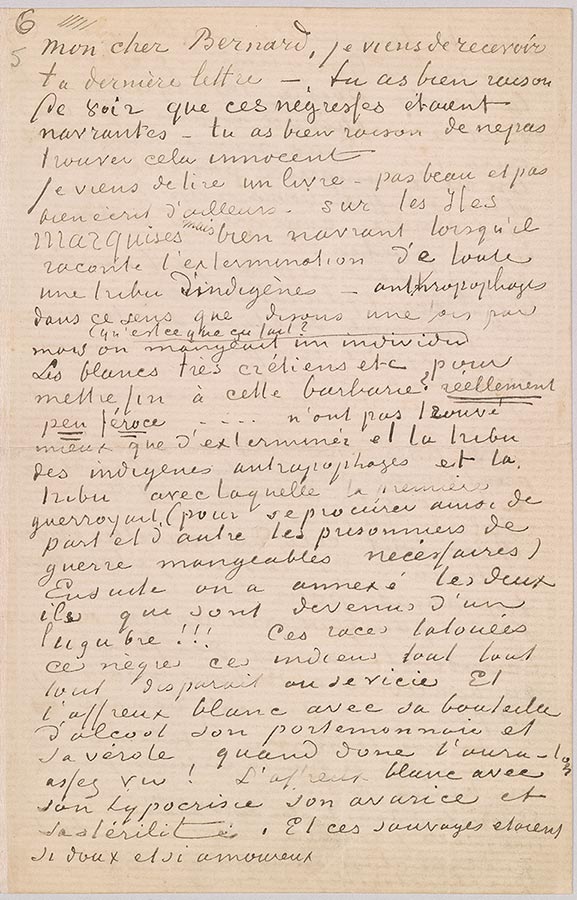

Letter 5, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, ca. 22 May 1888, Letter 5, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear Bernard,

I've just received your last letter—you're quite right to see that those negresses were heartrending—

you're quite right not to find it innocent.

I've just read a book—not beautiful and not well written, by the way—on the Marquesas Islands,

but very heartrending in its description of the extermination of an entire tribe of natives—cannibals

in the sense that let's say an individual was eaten once a month, and what of that?

The whites, very Christian, etc., to put an end to this barbarity? REALLY NOT VERY SAVAGE. . . .

could think of nothing better than to exterminate both the tribe of cannibal natives and the tribe

with which the former was at war (in order to obtain the requisite edible prisoners of war on both

sides). Then the two islands were annexed, and did they become dismal!!! Those tattooed races, those

negroes, those Indians, everything, everything, everything disappears or is corrupted. And the frightful

white man, with his bottle of alcohol, his wallet and his pox, when will we have seen enough of

him! The frightful white man, with his hypocrisy, his greed and his sterility! And those savages were

so gentle and so loving.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

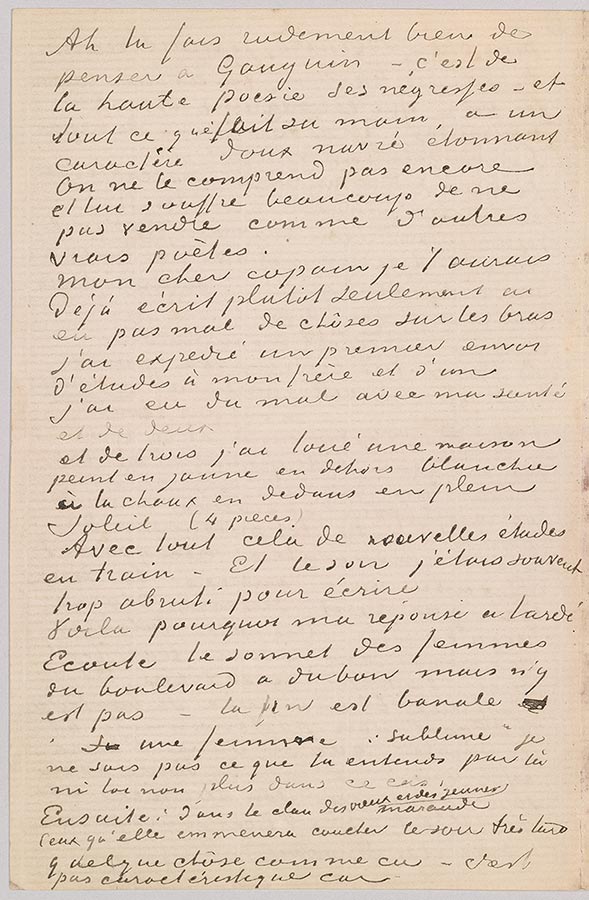

Letter 5, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, ca. 22 May 1888, Letter 5, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Ah, you do darned well to think of Gauguin—they're high poetry, his negresses—and everything

his hand makes has a sweet, heartrending, astonishing character. People don't understand him yet,

and he suffers greatly from not selling, like other true poets.

My dear pal, I would have written to you sooner, only have had quite a few things on my hands;

I've sent a first batch of studies to my brother is one, I've had trouble with my health is two, and

three is that I've rented a house painted yellow outside, whitewashed inside, in the full sun

(four rooms).

With all that, new studies in progress. And in the evening I was often too numbed to write.

That's why my reply was delayed.

Listen, the sonnet about the women of the boulevard has some good things, but it isn't there

yet—the end's banal.

A "sublime" woman, I don't know what you mean by that, nor do you in this case.

Then

"Hunting among the clan of old and young

Those whom she'll take to bed late at night."

Something like that—It's not characteristic, because

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

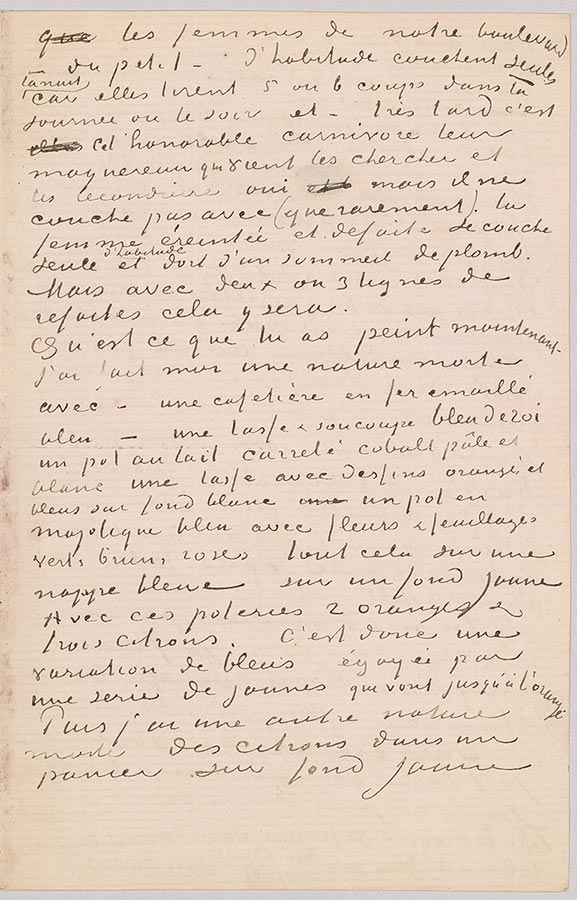

Letter 5, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, ca. 22 May 1888, Letter 5, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

the women of our boulevard—le petit—usually

sleep alone at night because they screw five or six times during the day or the evening and—late at

night it's that honorable carnivore, their pimp, who comes to collect them and take them home; yes,

but he doesn't sleep with them (only rarely). The worn-out and haggard woman usually goes to bed

alone and sleeps a leaden sleep. But with two or three lines redone, it'll be there.

What have you painted now? I myself have done a still life with—a coffeepot in blue enameled

iron—a royal blue cup and saucer, a milk jug with pale cobalt and white checks, a cup with orange

and blue designs on a white background, a blue majolica jug with green, brown, pink flowers and

foliage, all of it on a blue tablecloth against a yellow background. With these pieces of crockery,

two oranges, and three lemons. It's thus a variation of blues enlivened by a series of yellows ranging

all the way to orange.

Then I have another still life, some lemons in a basket against a yellow background.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

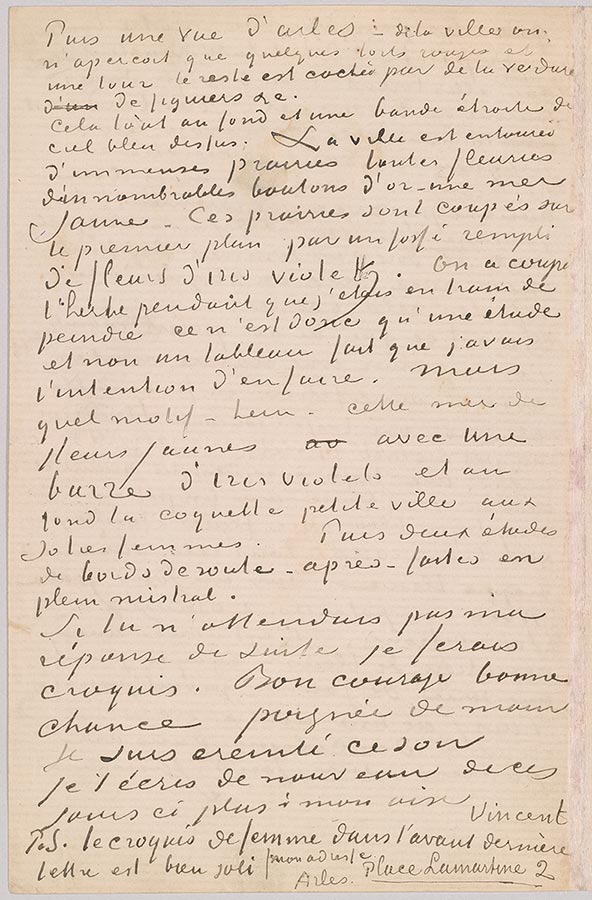

Letter 5, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, ca. 22 May 1888, Letter 5, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Then a view of Arles—of the town you see only a few red roofs and a tower, the rest's hidden by

the foliage of fig trees, etc.

All that far off in the background and a narrow strip of blue sky above. The town is surrounded

by vast meadows decked with innumerable buttercups—a yellow sea. These meadows are intersected

in the foreground by a ditch full of purple irises. They cut the grass while I was painting, so it's only

a study and not a finished painting, which I intended to make of it. But what a subject—eh—that

sea of yellow flowers with a line of purple irises and in the background the neat little town of pretty

women. Then two studies of roadsides—afterwards—done out in the mistral.

If you were not expecting my reply right away, I'd make sketches. Courage, good luck, handshake.

I'm worn out this evening.

I'll write to you again one of these days, more at my ease.

Vincent

P.S. The sketch of the woman in the last letter but one is really pretty.

My address:

Place Lamartine 2

Arles

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

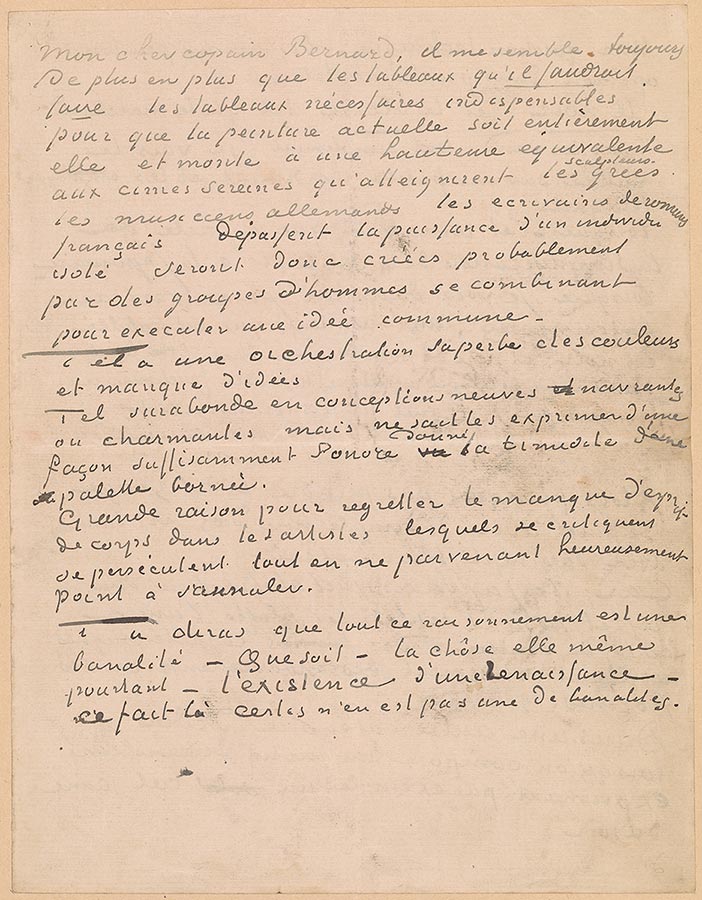

Letter 6, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear old Bernard,

More and more it seems to me that the paintings that ought to be made, the paintings that are

necessary, indispensable for painting today to be fully itself and to rise to a level equivalent to the

serene peaks achieved by the Greek sculptors, the German musicians, the French writers of novels,

exceed the power of an isolated individual, and will therefore probably be created by groups of men

combining to carry out a shared idea.

One has a superb orchestration of colors and lacks ideas.

The other overflows with new, harrowing or charming conceptions but is unable to express

them in a way that is sufficiently sonorous, given the timidity of a limited palette.

Very good reason to regret the lack of an esprit de corps among artists, who criticize each

other, persecute each other, while fortunately not succeeding in canceling each other out.

You'll say that this whole argument is a banality. So be it—but the thing itself—the existence

of a Renaissance—that fact is certainly not a banality.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

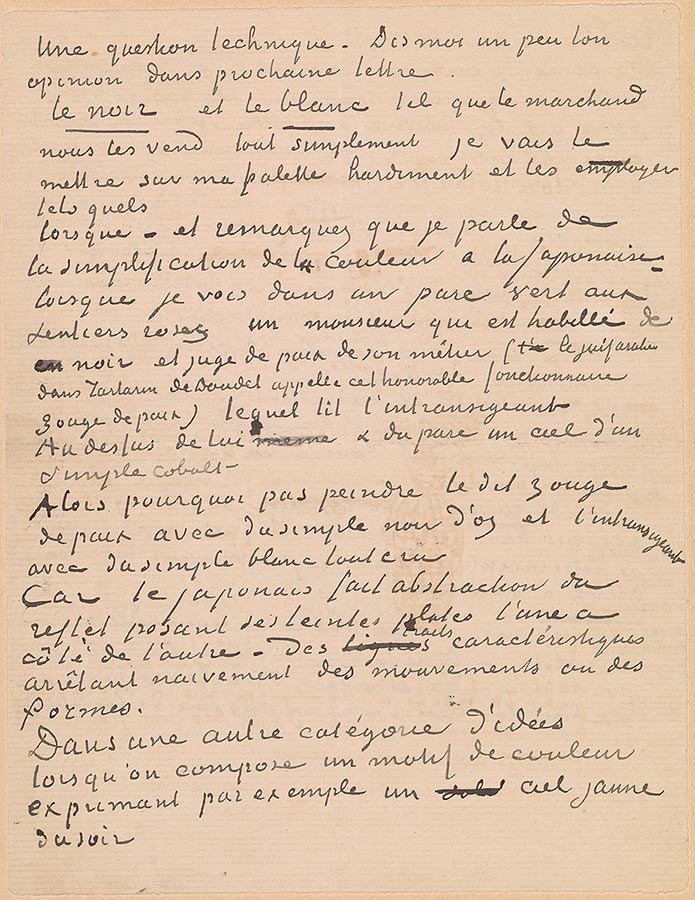

Letter 6, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

A technical question. Do give me your opinion in next letter.

I'm going to put the black and the white boldly on my palette, just the way the colorman sells

them to us, and use them as they are.

When—and note that I'm talking about the simplification of color in the Japanese manner—

when I see in a green park with pink paths a gentleman who is dressed in black, and a justice of the

peace by profession (the Arab Jew in Daudet's Tartarin calls this honorable official "shustish of the beace"), who's reading L'Intransigeant.

Above him and the park a sky of a simple cobalt.

Then why not paint the said shustish of the beace with simple bone black and L'Intransigeant

with simple, very harsh white?

Because the Japanese disregards reflection, placing his solid tints one beside the other—

characteristic lines naively marking off movements or shapes.

In another category of ideas, when you compose a color motif expressing, for example, a

yellow evening sky.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

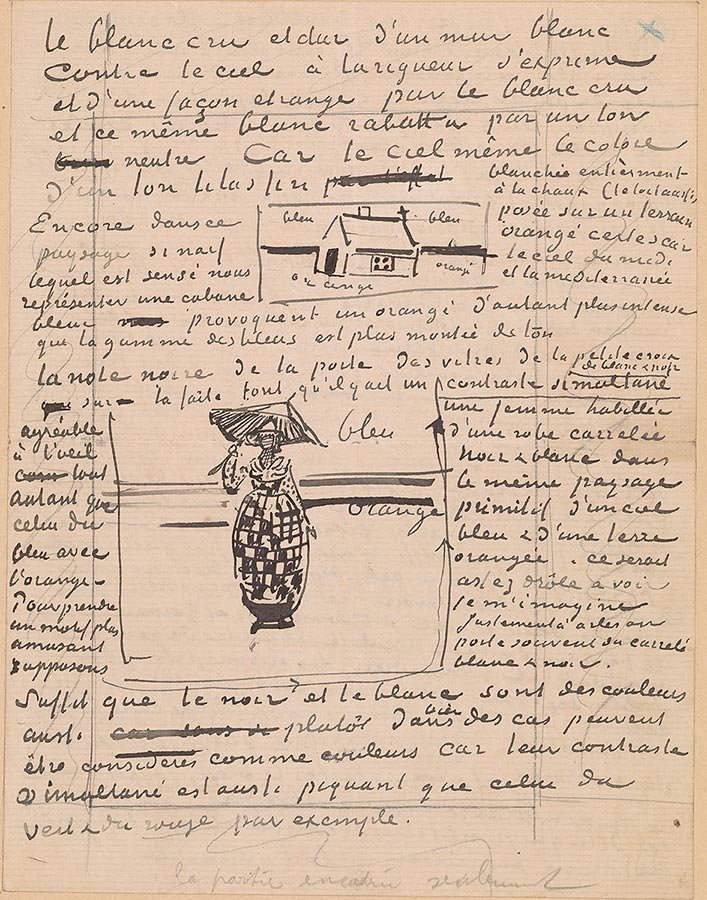

Letter 6, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

The harsh, hard white of a white wall against the sky can be expressed, at a pinch and in a

strange way, by harsh white and by that same white softened by a neutral tone. Because the sky

itself colors it with a delicate lilac hue. Again, in this very naive landscape, which is meant

to show us a hut, whitewashed overall (the roof, too), placed in an orange field, of course, because

the sky in the south and the blue Mediterranean produce an orange that is all the more intense

the higher in tint the range of blues.

The black note of the door, of the windowpanes, of the little cross on the rooftop creates a

simultaneous contrast of white and black just as pleasing to the eye as that of the blue

with the orange.

To take a more entertaining subject, let's imagine a woman dressed in a black and white

checked dress, in the same primitive landscape of a blue sky and an orange earth—that would

be quite amusing to see, I imagine. In fact, in Arles they often do wear white and black checks.

In short, black and white are colors too, or rather, in many cases may be considered colors, since their simultaneous contrast is as sharp as that of green and red, for example.

>© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 6, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

The Japanese use it too, by the way—they express a young girl's matte and pale complexion,

and its sharp contrast with her black hair wonderfully well with white paper and four strokes of the

pen. Not to mention their black thornbushes, studded with a thousand white flowers.

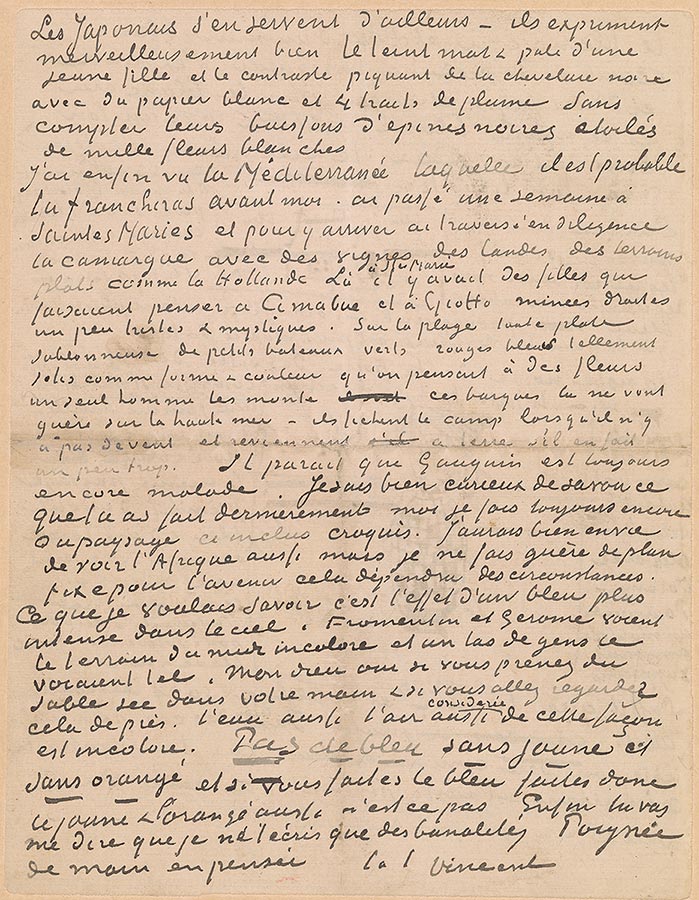

I've finally seen the Mediterranean, which you will probably cross before I do. Spent a week

in Saintes-Maries, and to get there crossed the Camargue in a diligence, with vineyards, heaths,

fields as flat as Holland. There, at Saintes-Maries, there were girls who made one think of Cimabue

and Giotto: slim, straight, a little sad and mystical. On the completely flat, sandy beach, little

green, red, blue boats, so pretty in shape and color that one thought of flowers; one man boards

them, these boats hardly go on the high sea—they dash off when there's no wind and come back to

land if there's a bit too much. It appears that Gauguin is still ill. I'm quite curious to know what

you've done lately; I'm still doing landscapes, sketch enclosed. I'd very much like to see Africa too,

but I hardly make any firm plans for the future, it will depend on circumstances. What I should like

to know is the effect of a more intense blue in the sky. Fromentin and Gérôme see the earth in

the south as colorless, and a whole lot of people saw it that way. My God, yes, if you take dry sand

in your hand and if you look at it closely. Water, too, air, too, considered this way, are colorless. No

BLUE WITHOUT YELLOW and WITHOUT ORANGE, and if you do blue, then do yellow and orange as

well, surely. Ah well, you'll tell me that I write you nothing but banalities. Handshake in thought,

Ever yours,

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

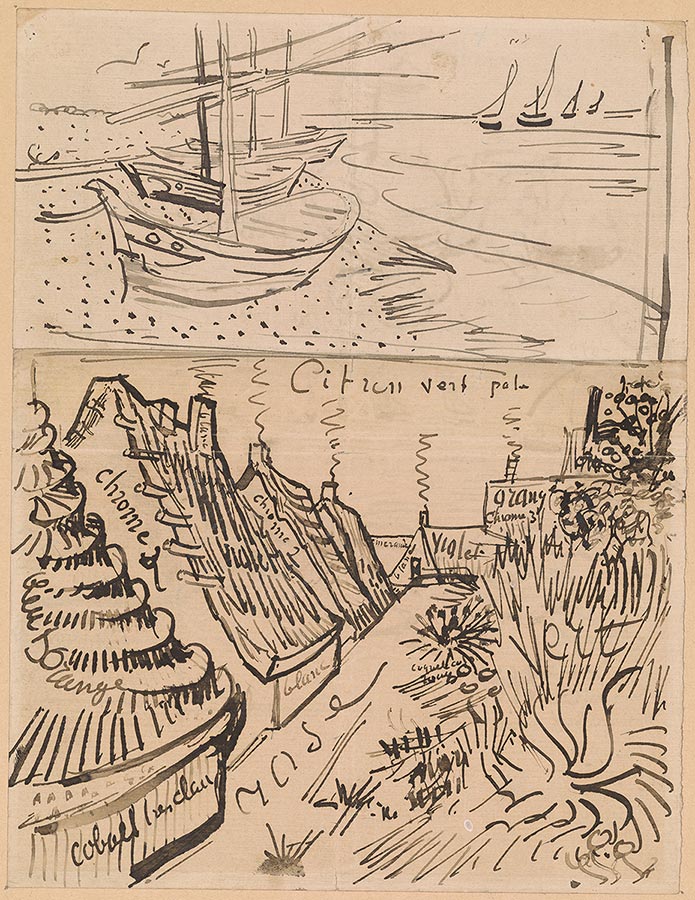

Letter 6, page 5

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 5

Street in Saintes-Maries

Fishing boats on the beach

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Van Gogh deeply felt the need for a lively dialogue and collaboration among artists. He argued that for modern art to rival, for example, the accomplishments of ancient Greek sculptors, artists should work collectively on a shared idea, since the "paintings that ought to be made . . . exceed the power of an isolated individual." Included in this letter is a sketch of a still life with a blue enameled coffeepot. Bernard would have recognized it as an homage to his own painting made six months earlier while the two artists were in Paris. The sketch of the street in Saintes-Maries documents his freshly painted canvas, with copious notations of the pairs of complementary colors he employed.

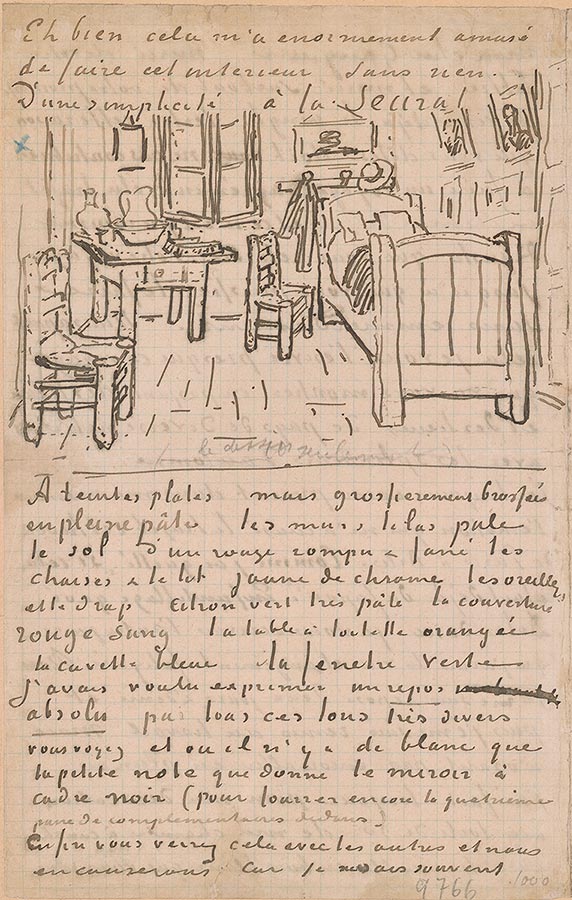

Upon his return from an intensely productive journey to the seaside town of Saintes-Maries, van Gogh sent this letter with a sheet of sketches enclosed to Bernard. The care he took with the drawings shows that he was eager to communicate the excitement of his work resulting from the trip. Inspired by the vibrant and constantly changing colors of the Mediterrenean, he described the beached fishing boats as being "so pretty in shape and color that one thought of flowers." He included a quick sketch of the boats along with outlines of another seascape, and two landscapes he was working on. In the letter he continued to discuss his theories about color and the use of black and white, adding a sketch of a woman in a black and white checked dress to emphasize the need to use such pigments boldly. He then jotted down a small sketch of one of the local cottages that became the subject for several drawings and paintings.

Letter 6, page 6

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 6

Still life with coffee pot

Fishing boats at sea; Landscape with edge of a road; Farm along a road

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Van Gogh deeply felt the need for a lively dialogue and collaboration among artists. He argued that for modern art to rival, for example, the accomplishments of ancient Greek sculptors, artists should work collectively on a shared idea, since the "paintings that ought to be made . . . exceed the power of an isolated individual." Included in this letter is a sketch of a still life with a blue enameled coffeepot. Bernard would have recognized it as an homage to his own painting made six months earlier while the two artists were in Paris. The sketch of the street in Saintes-Maries documents his freshly painted canvas, with copious notations of the pairs of complementary colors he employed.

Upon his return from an intensely productive journey to the seaside town of Saintes-Maries, van Gogh sent this letter with a sheet of sketches enclosed to Bernard. The care he took with the drawings shows that he was eager to communicate the excitement of his work resulting from the trip. Inspired by the vibrant and constantly changing colors of the Mediterrenean, he described the beached fishing boats as being "so pretty in shape and color that one thought of flowers." He included a quick sketch of the boats along with outlines of another seascape, and two landscapes he was working on. In the letter he continued to discuss his theories about color and the use of black and white, adding a sketch of a woman in a black and white checked dress to emphasize the need to use such pigments boldly. He then jotted down a small sketch of one of the local cottages that became the subject for several drawings and paintings.

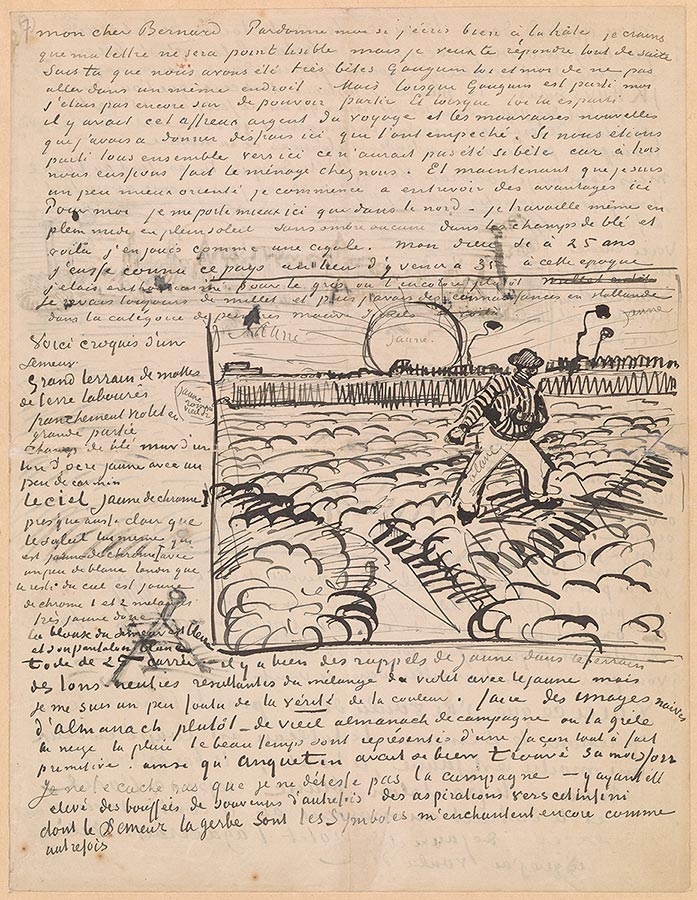

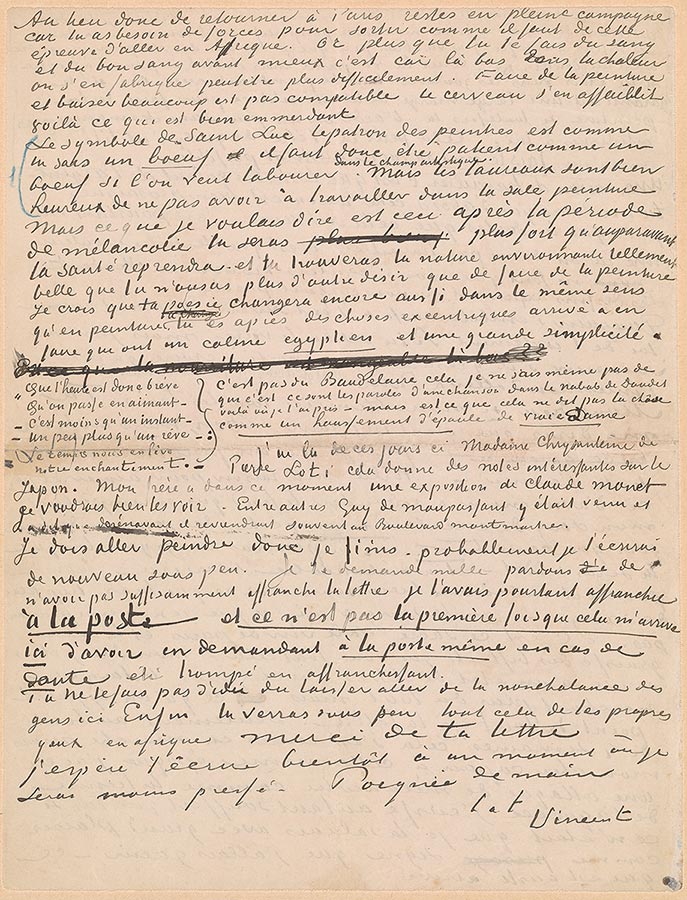

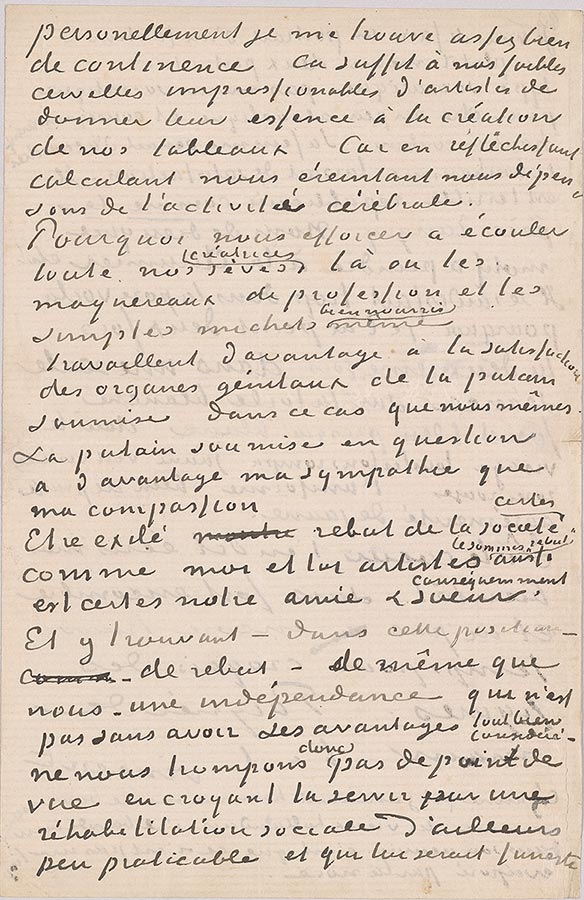

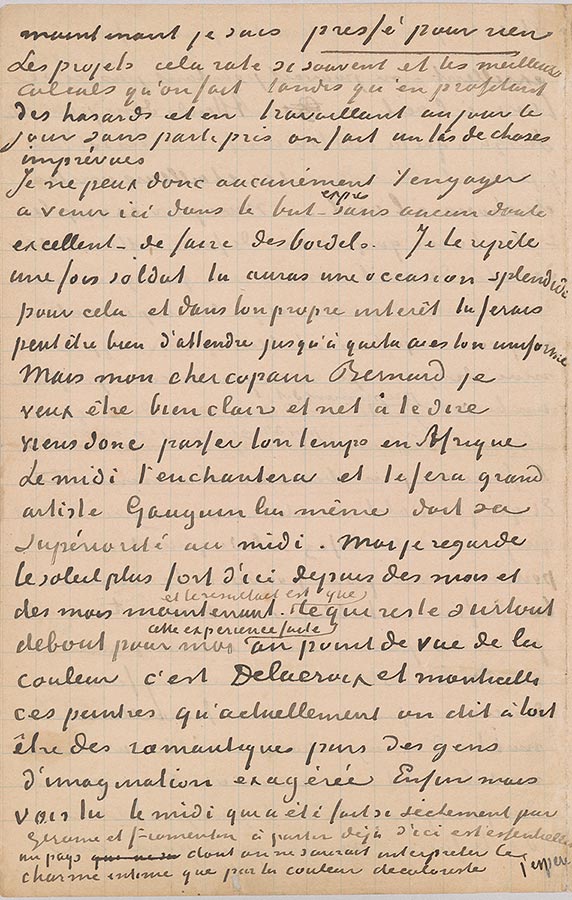

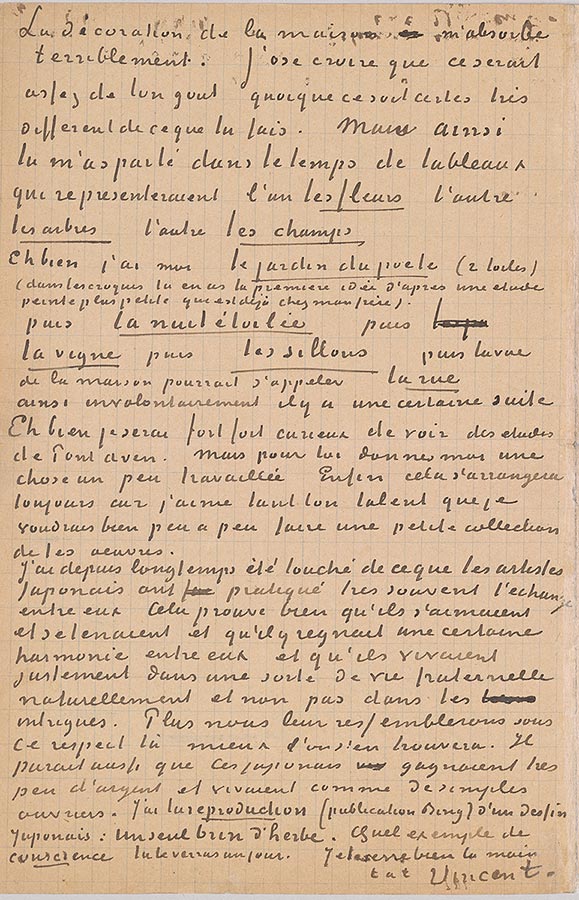

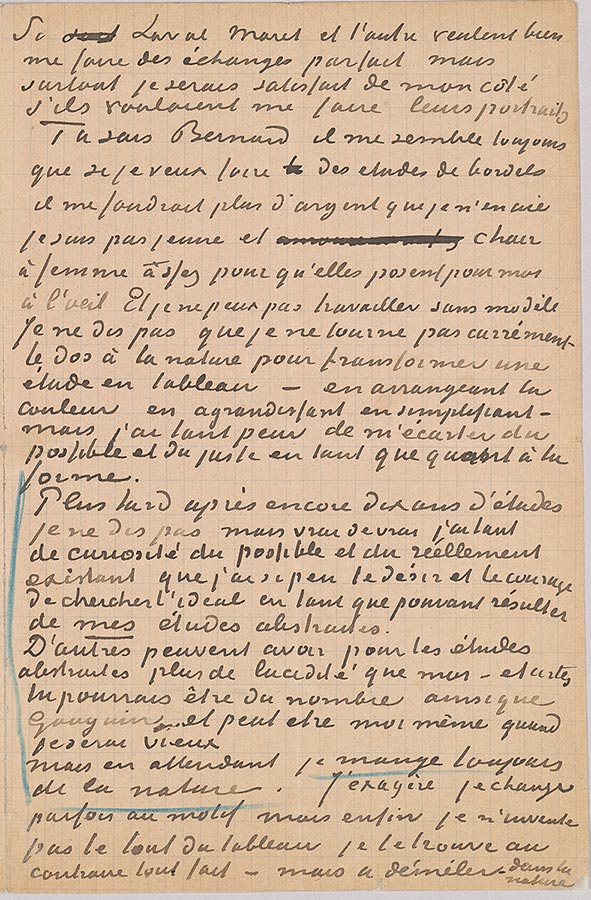

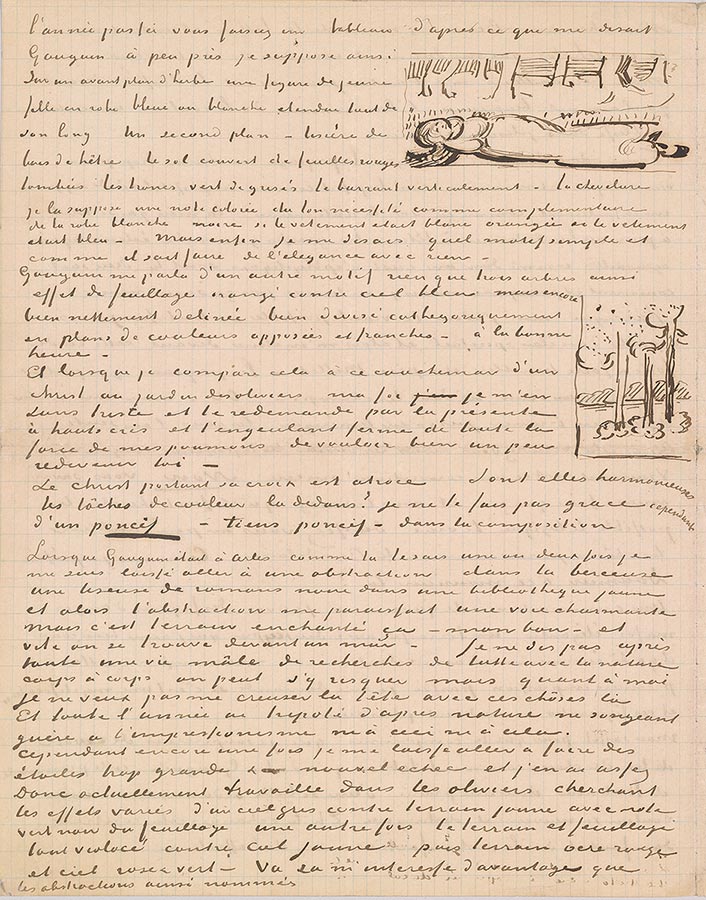

Letter 7, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 19 June 1888, Letter 7, page 1

Sower with setting sun

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear Bernard,

Forgive me if I write in great haste; I fear that my letter won't be at all legible, but I want to reply to

you right away.

Do you know that we've been very foolish, Gauguin, you, and I, in not all going to the same

place? But when Gauguin left, I wasn't yet sure of being able to leave. And when you left, there was

that dreadful money for the fare, and the bad news I had to give about the expenses here, which

prevented it. If we had all left for here together it wouldn't have been so foolish, because the three

of us would have done our own housekeeping. And now that I've found my bearings a little more,

I'm beginning to see the advantages here. For myself, I'm in better health here than in the north—I

even work in the wheat fields at midday, in the full heat of the sun, without any shade whatever,

and there you are, I revel in it like a cicada. My God, if only I had known this country at twenty-five,

instead of coming here at thirty-five—In those days I was enthusiastic about gray, or rather,

absence of color. I was always dreaming about Millet, and then I had acquaintances in the category

of painters like Mauve, Israëls. Here's sketch of a sower.

Large field with clods of plowed earth, mostly downright violet.

Field of ripe wheat in a yellow ocher tone with a little crimson.

The chrome yellow 1 sky almost as bright as the sun itself, which is chrome yellow 1 with a

little white, while the rest of the sky is chrome yellow 1 and 2 mixed, very yellow, then.

The sower's smock is blue, and his trousers white. Square no. 25 canvas. There are many repetitions of yellow in the earth, neutral tones, resulting from the mixing of violet with yellow, but I

could hardly give a damn about the veracity of the color. Better to make naive almanac pictures—old

country almanacs, where hail, snow, rain, fine weather are represented in an utterly primitive way. The

way Anquetin got his Harvest so well.

I don't hide from you that I don't detest the countryside—having been brought up there, snatches

of memories from past times, yearnings for that infinite of which the sower, the sheaf, are the symbols,

still enchant me as before.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

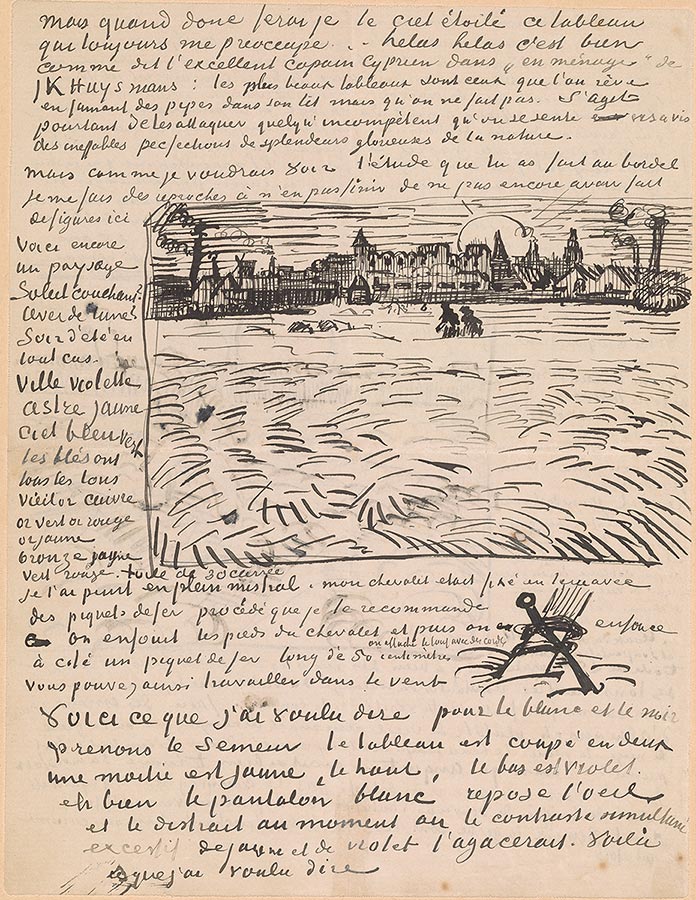

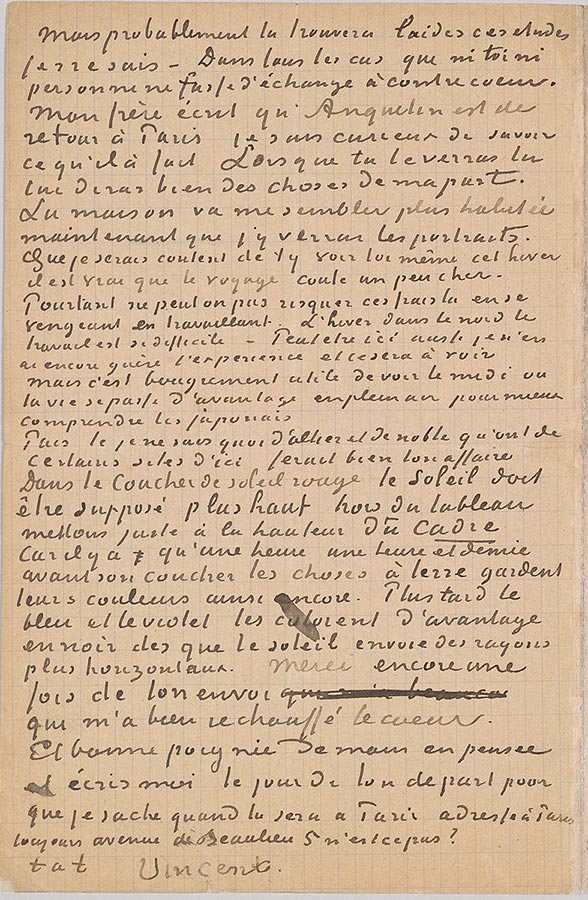

Letter 7, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 19 June 1888, Letter 7, page 2

Wheatfield with setting sun); Leg of an easel with a ground spike

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I don't hide from you that I don't detest the countryside—having been brought up there, snatches of memories from past times, yearnings for that infinite of which the sower, the sheaf, are the symbols, still enchant me as before.

But when will I do the starry sky, then, that painting that's always on my mind? Alas, alas, it's just as our excellent pal Cyprien says, in "En ménage" by J. K. Huysmans, the most beautiful paintings are those one dreams of while smoking a pipe in one's bed but which one doesn't make. But it's a matter of attacking them nevertheless, however incompetent one may feel vis-à-vis the ineffable perfections of nature's glorious splendors.

But how I should like to see the study you did at the brothel. I reproach myself endlessly for not having done figures here yet. Here's another landscape.11 Setting sun? Moonrise? Summer evening, at any rate.

Town violet, star yellow, sky blue green; the wheat fields have all the tones: old gold, copper, green gold, red gold, yellow gold, green, red and yellow bronze. Square no. 30 canvas.

I painted it out in the mistral. My easel was fixed in the ground with iron pegs, a method that I recommend to you. You shove the feet of the easel in and then you push a 50-centimeter-long iron peg in beside them. You tie everything together with ropes; that way you can work in the wind.

Here's what I wanted to say about the white and the black. Let's take the Sower. The painting is divided into two; one half is yellow, the top; the bottom is violet. Well, the white trousers rest the eye and distract it just when the excessive simultaneous contrast of yellow and violet would annoy it. That's what I wanted to say.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 7, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 19 June 1888, Letter 7, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I know a second lieutenant of Zouaves here called Milliet. I give him drawing lessons—with my

perspective frame—and he's beginning to make drawings—my word, I've seen a lot worse than

that, and he's eager to learn; has been to Tonkin, etc. He's leaving for Africa in October. If you were

in the Zouaves, he'd take you with him and would guarantee you a wide margin of relative freedom

to paint, provided you helped him a little with his own artistic schemes. Could this be of some use

to you? If so, let me know as soon as possible.

One reason for working is that canvases are worth money. You'll tell me that first of all this reason is

very prosaic, then that you doubt that it's true. But it's true. A reason for not working is that in the

meantime canvases and paints only cost us money. Drawings, though, don't cost us much.

Gauguin's bored too in Pont-Aven; complains about isolation, like you. If you went to see

him—but I have no idea if he'll stay there, and am inclined to think that he intends to go to Paris.

He said that he thought you would have come to Pont-Aven.

My God, if all three of us were here! You'll tell me it's too far away. Fine, but in winter—because

here one can work outside all year round. That's my reason for loving this part of the world, not

having to dread the cold so much, which by preventing my blood from circulating prevents me from

thinking, from doing anything at all. You can judge that for yourself when you're a soldier. Your melancholy will go away, which may darned well come from the fact that you have too little blood—

or spoiled blood, which I don't think, however. It's that bloody filthy Paris wine and the filthy fat

of the steaks that do that to you—dear God, I had come to a state in which my own blood was no

longer working at all, but literally not at all, as they say. But after 4 weeks down here it got moving

again, but, my dear pal, at that same time I had an attack of melancholy like yours, from which I

would have suffered as much as you were it not that I welcomed it with great pleasure as a sign that

I was going to recover—which happened too.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 7, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 19 June 1888, Letter 7, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Instead of going back to Paris, then, stay out in the country, because you need strength to get

through this ordeal of going to Africa properly. Now the more blood, and good blood, that you

make yourself beforehand, the better, because over there in the heat it's perhaps harder to produce it.

Painting and fucking a lot are not compatible; it weakens the brain, and that's what's really damned

annoying.

The symbol of Saint Luke, the patron of painters, is, as you know, an ox; we must therefore be as

patient as an ox if we wish to labor in the artistic field. But bulls are pretty glad not having to work

in the filthy business of painting. But what I wanted to say is this. After the period of melancholy

you'll be stronger than before, your health will pick up—and you'll find the surrounding nature so

beautiful that you'll have no other desire than to paint. I believe that your poetry will also change, in

the same way as your painting. After some eccentric things you have succeeded in making some that

have an Egyptian calm and a great simplicity.

How short is the hour

We spend loving—

—It's less than an instant—

—A little more than a dream—:

—Time takes away

—Our spell.

That's not Baudelaire, I don't even know who it's by, they're the words of a song in Daudet's Le

Nabab, that's where I took it from—but doesn't it say the thing like a real Lady's shrug of her shoulder?

These last few days I read Pierre Loti's Madame Chrysanthème; it provides interesting remarks

about Japan. At the moment my brother has an exhibition of Claude Monet, I'd very much like to

see them. Guy de Maupassant, among others, had been there, and said that from now on he would

often revisit the boulevard Montmartre.

I have to go and paint, so I'll finish—I'll probably write to you again before long. I beg a thousand

pardons for not having put enough stamps on the letter, and yet I did stamp it at the post office and

this isn't the first time that it's happened here, that when in doubt, and asking at the post office itself, I've

been misled about the postage.

You can't imagine the carelessness, the nonchalance of the people here. Anyway, you'll see that

shortly with your own eyes in Africa. Thanks for your letter, I hope to write to you soon at a moment

when I'm in less of a hurry. Handshake,

Ever yours,

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

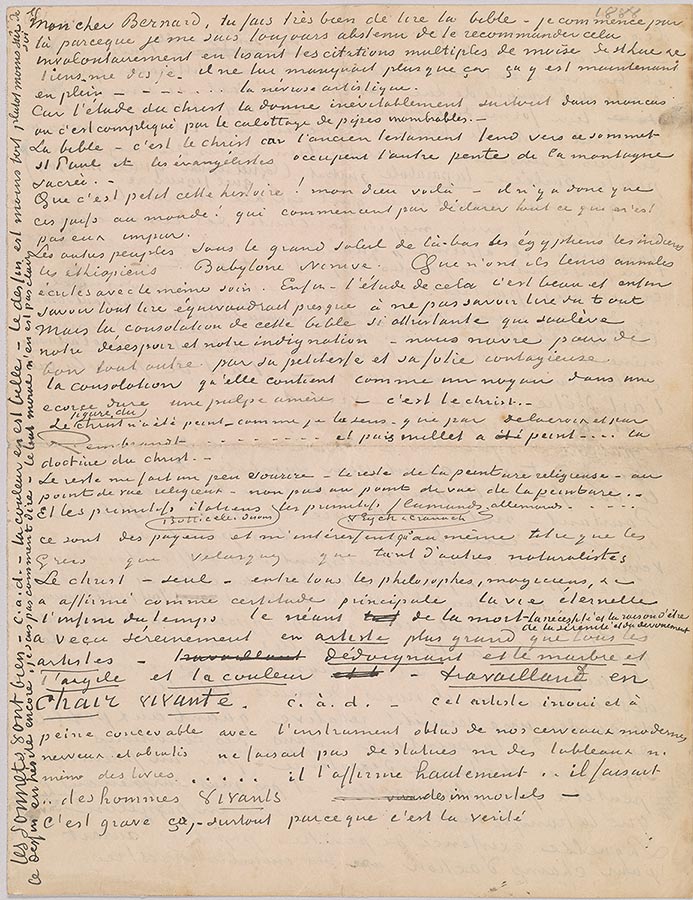

Letter 8, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 26 June 1888, Letter 8, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear Bernard,

You do very well to read the Bible—I start there because I've always refrained from recommending

it to you.

When reading your many quotations from Moses, from St. Luke, etc., I can't help saying to

myself—well, well—that's all he needed. There it is now, full-blown—. . . the artist's neurosis.

Because the study of Christ inevitably brings it on, especially in my case, where it's complicated

by the seasoning of innumerable pipes.

The Bible—that's Christ, because the Old Testament leads toward that summit; St. Paul and the

evangelists occupy the other slope of the holy mountain.

How petty that story is! My God, are there only these Jews in the world, then? Who start out by

declaring that everything that isn't themselves is impure?

The other peoples under the great sun over there—the Egyptians, the Indians, the Ethiopians,

Babylon, Nineveh. Why didn't they write their annals with the same care? Still, the study of it is

beautiful, and anyway, to be able to read everything would be almost the equivalent of not being

able to read at all. But the consolation of this so saddening Bible, which stirs up our despair and

our indignation—thoroughly upsets us, completely outraged by its pettiness and its contagious

folly the consolation it contains, like a kernel inside a hard husk, a bitter pulp—is Christ. The

figure of Christ has been painted—as I feel it—only by Delacroix and by Rembrandt . . . And then

Millet has painted . . . Christ's doctrine.

The rest makes me smile a little—the rest of religious painting—from the religious point of

view—not from the point of view of painting. And the Italian primitives (Botticelli, say), the Flemish,

German primitives (V. Eyck, & Cranach) . . . They're pagans, and only interest me for the same

reason as the Greeks do, and Velázquez, and so many other naturalists. Christ—alone—among all

the philosophers, magicians, etc., declared eternal life—the endlessness of time, the nonexistence of

death—to be the principal certainty. The necessity and the raison d'être of serenity and devotion.

Lived serenely as an artist greater than all artists—disdaining marble and clay and paint—working

in LIVING FLESH. I.e.—this extraordinary artist, hardly conceivable with the obtuse instrument

of our nervous and stupefied modern brains, made neither statues nor paintings nor even books . . .

he states it loud and clear . . . he made . . . LIVING men, immortals.

That's serious, you know, especially because it's the truth.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

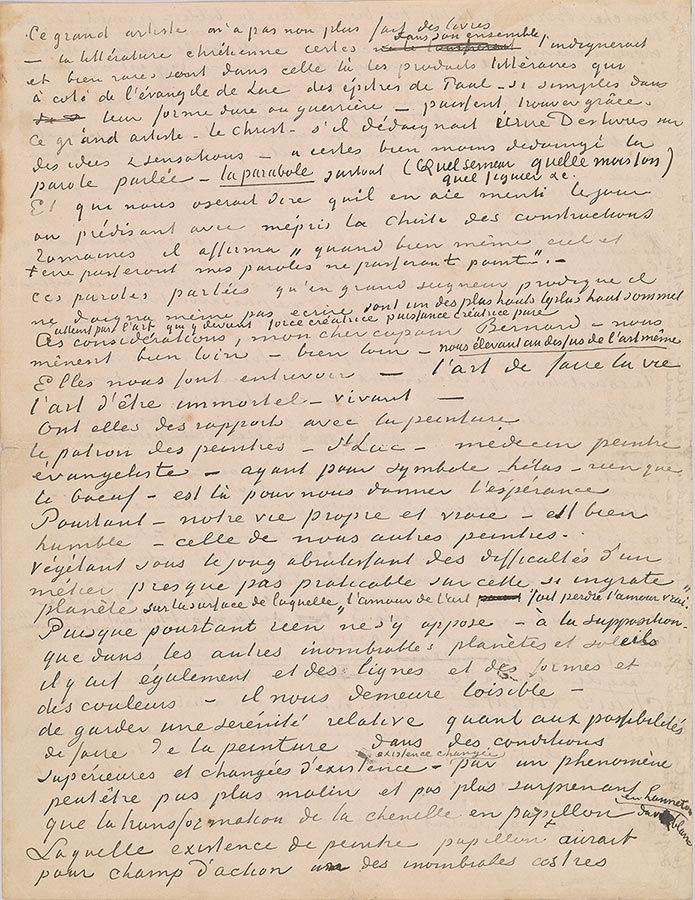

Letter 8, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 26 June 1888, Letter 8, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

That great artist didn't make books, either—Christian literature as a whole would certainly

infuriate him, and its literary products that could find favor beside Luke's gospel, Paul's epistles—so

simple in their hard or warlike form—are few and far between. This great artist—Christ—although

he disdained writing books on ideas & feelings—was certainly much less disdainful of the spoken

word—THE PARABLE above all. (What a sower, what a harvest, what a fig-tree, etc.)

And who would dare tell us that he lied, the day when, scornfully predicting the fall of the buildings

of the Romans, he stated, "heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away?"

Those spoken words, which as a prodigal, great lord he did not even deign to write down,

are one of the highest, the highest summit attained by art, which in them becomes a creative force,

a pure creative power.

These reflections, my dear old Bernard—take us a very long way—a very long way—raising us

above art itself. They enable us to glimpse—the art of making life, the art of being immortal—alive.

Do they have connections with painting? The patron of painters—St. Luke—physician, painter,

evangelist—having for his symbol—alas—nothing but the ox—is there to give us hope.

Nevertheless—our own real life—is humble indeed—our life as painters.

Stagnating under the stupefying yoke of the difficulties of a craft almost impossible to practice

on this so hostile planet, on the surface of which "love of art makes one lose real love."

Since, however, nothing stands in the way—of the supposition that on the other innumerable

planets and suns there may also be lines and shapes and colors—we are still at liberty—to retain

a relative serenity as to the possibilities of doing painting in better and changed conditions of existence—

an existence changed by a phenomenon perhaps no cleverer and no more surprising than

the transformation of the caterpillar into a butterfly, of the white grub into a cockchafer.

That existence of painter as butterfly would have for its field of action one of the innumerable

stars,

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

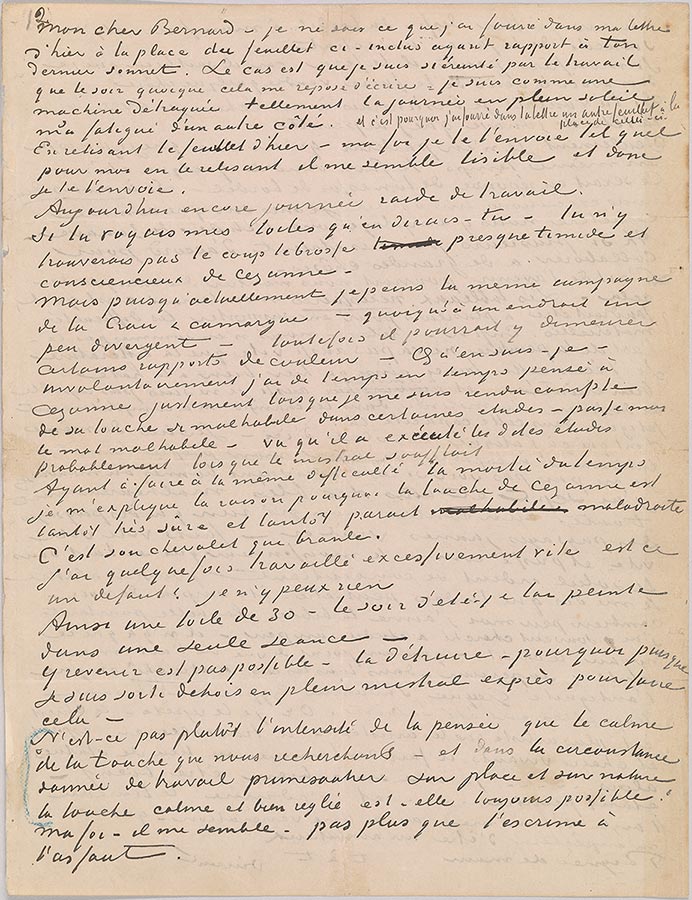

Letter 8, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 26 June 1888, Letter 8, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

which, after death, would perhaps be no more unapproachable, inaccessible to us than the

black dots that symbolize towns and villages on the map in our earthly life. Science—scientific

reasoning—seems to me to be an instrument that will go a very long way in the future.

Because, look—it was thought that the earth was flat—that was true—it still is today—from

Paris to Asnières, for example.

But that didn't prevent science proving that the earth is above all round. Which nobody

disputes nowadays.

Now at present, despite that, we're still in the position of believing that life is flat and goes from

birth to death.

But life too is probably round, and far superior in extent and potentialities to the single hemisphere

that is known to us at present.

Future generations—probably—will enlighten us on this subject that is so interesting—and

then science itself—could—with all due respect—reach conclusions more or less parallel to Christ's

words concerning the other half of existence.

Whatever the case—the fact is that we are painters in real life, and it's a matter of breathing

one's breath as long as one has breath.

Ah—E. DELACROIX'S beautiful painting—Christ's boat on the sea of Gennesaret, he—with his

pale lemon halo—sleeping, luminous—within the dramatic violet, dark blue, blood-red patch of

the group of stunned disciples. On the terrifying emerald sea, rising, rising all the way up to the top

of the frame. Ah—the brilliant sketch.

I would make you some sketches were it not that having drawn and painted for three or four

days with a model—a Zouave—I'm exhausted—on the contrary, writing is restful and diverting.

What I've done is bloody ugly: a drawing of the Zouave, seated, a painted sketch of the Zouave

against an all-white wall and lastly his portrait against a green door and some orange bricks of a

wall. It's harsh and, well, ugly and badly done. However, since that's the real difficulty attacked, it

may smooth the way in the future. The figures that I do are almost always detestable in my own eyes,

and all the more so in others' eyes—nevertheless, it's the study of the figure that strengthens us the

most, if we do it in a different way than we're taught at Monsieur Benjamin Constant's, for example.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 8, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 26 June 1888, Letter 8, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Your letter gave me great pleasure—the SKETCH IS VERY INTERESTING and I do

thank you for it—for my part I'll send you a drawing one of these days—this evening I'm too worn

out in that respect; my eyes are tired, not to mention my brain.

Listen—do you remember John the Baptist by Puvis? I find it marvelous and as much the

MAGICIAN as Eugène Delacroix.

The passage about John the Baptist that you dug out of the gospel is absolutely what you saw

in it . . . People pressing around somebody—art thou Christ, art thou Elias? As it would be in our

day to ask impressionism or one of its searcher-representatives, "have you found it?" That's just it.

At the moment my brother has an exhibition of Claude Monet—10 paintings done in Antibes

from February to May. It seems it's very beautiful.

Have you ever read the life of Luther? Because Cranach, Dürer, Holbein belong to him—it's

he—his personality—that's the lofty light of the Middle Ages.

I like the Sun King no more than you do—extinguisher of light it rather seems to me—that

Louis xiv—my God, what a pain, in every way, that Methodist Solomon. I don't like Solomon

either, and the Methodists not at all, as well. Solomon seems a hypocritical pagan to me; I really

have no respect for his architecture, an imitation of other styles, nor for his writings, which the

pagans have done much better.

Tell me a bit about where you stand as far as your military service is concerned; should I talk

to that second lieutenant of Zouaves or not? Are you going to Africa or not? In your case, do the

years count double in Africa or not? Most of all, see that your blood's in order—you don't get very

far with anemia—painting goes slowly—better try to make your constitution as tough as old boots,

a constitution to make old bones—better live like a monk who goes to the brothel once a fortnight—

I do that, it's not very poetical—but anyway—I feel that my duty is to subordinate my life

to painting.

If I was in the Louvre with you, I'd really like to see the primitives with you.

In the Louvre, I still return with great love to the Dutch, Rembrandt first and foremost—

Rembrandt whom I once studied so thoroughly—then Potter, for example—who makes—on a

no. 4 or no. 6 panel, a white stallion alone in a meadow, a stallion neighing, and with a hard-on

—forlorn under a sky brewing up a thunderstorm—heartbroken in the tender green immensity of

a wet meadow—ah well, there are wonderful things in the old Dutchmen having no connection

with anything at all. Handshake, and thank you again for your letter and for your sketch.

Ever yours,

Vincent

The sonnets are going well—i.e.—the color in them is good—the design isn't as strong, less

sure of itself, rather; the conception's still hesitant, I don't know how to put it—its moral

purpose isn't clear.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

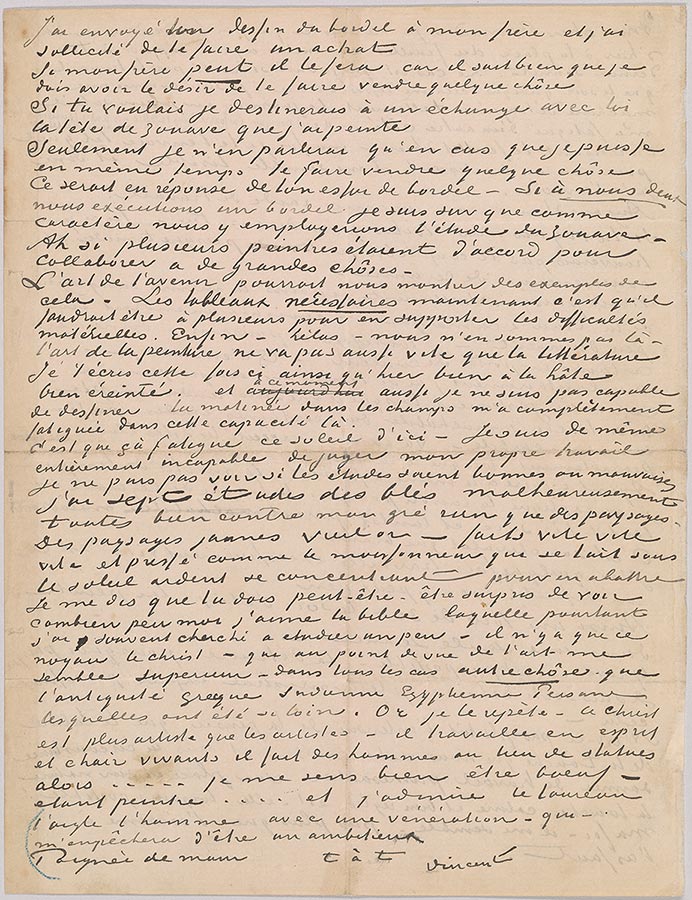

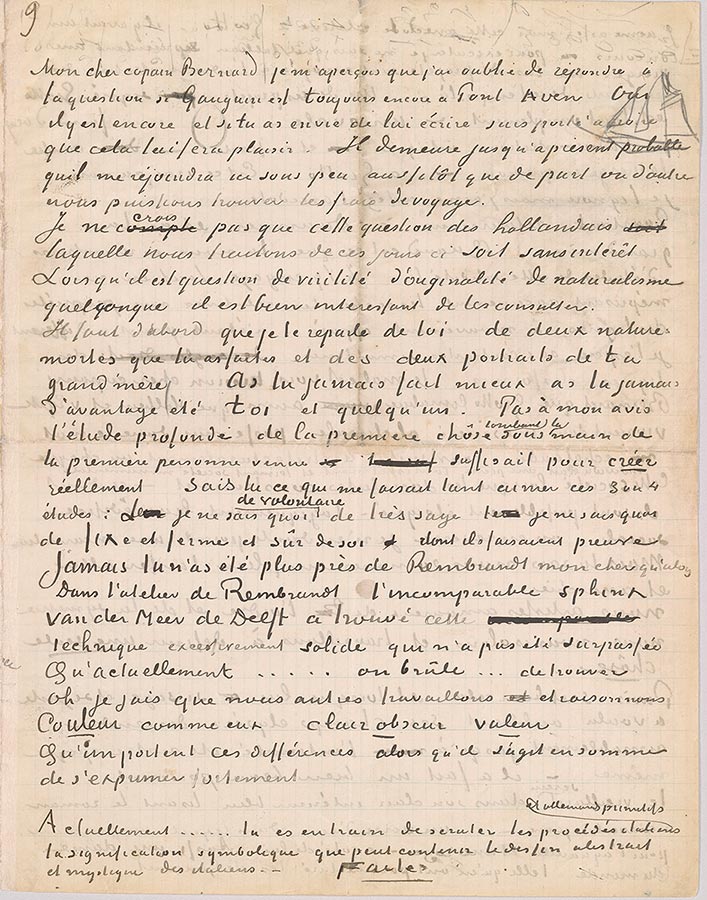

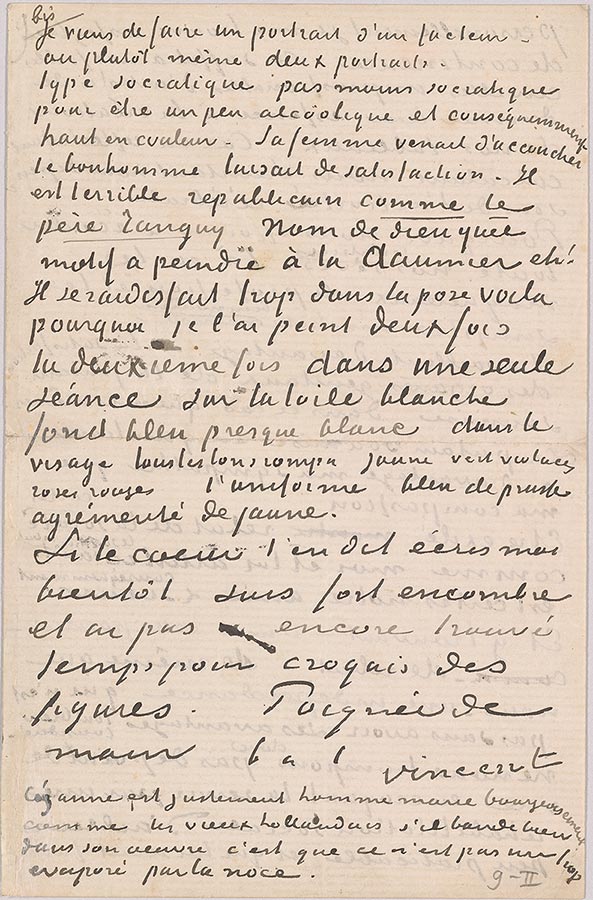

Letter 9, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 27 June 1888, Letter 9, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear Bernard—

I don't know what I stuck into my letter of yesterday instead of the enclosed sheet on the subject of

your last sonnet. The fact is that I am so worn out by work that in the evening—although writing

is restful for me—I'm like a broken-down machine, so much has the day in the full sun tired me

otherwise. And that's why I stuck another sheet into your letter instead of this one.

On rereading yesterday's sheet—well, I'm sending you it as it is; on rereading it, it seems legible

to me and so I'm sending you it.

Another hard day's work today.

If you saw my canvases, what would you say about them—you wouldn't find Cézanne's almost

diffident and conscientious brushstroke there.

But since at present I am painting the same countryside of La Crau and the Camargue—although in a slightly different place—nevertheless, certain color relationships could remain. What

do I know about it—from time to time I couldn't help thinking of Cézanne, particularly when I

realized that his touch is so clumsy in certain studies—disregard the word clumsy—seeing that he

probably executed those studies when the mistral was blowing.

Having to deal with the same difficulty half the time, I can explain why Cézanne's touch is

sometimes so sure and sometimes seems awkward. It's his easel that's wobbling.

I have sometimes worked excessively fast; is that a fault? I can't help it.

For example I've painted a no. 30 canvas—the summer evening—at a single sitting.

It's not possible to rework it; to destroy it—why, because I deliberately went outside to make it, out

in the mistral.

Isn't it rather intensity of thought than calmness of touch that we're looking for—and in the given

circumstances of impulsive work on the spot and from life, is a calm and controlled touch always possible?

Well—it seems to me—no more than fencing moves during an attack.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 9, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 27 June 1888, Letter 9, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I have sent your drawing of the brothel to my brother, and I've asked him to buy something of yours.

If my brother can, he'll do it, because he knows very well that I must want to have you sell something.

If you wished, I would earmark for an exchange with you the head of a Zouave that I've painted.

But I won't speak about it unless I can have you sell something at the same time.

That would be in response to your attempt at a brothel. If we executed a brothel together, I'm sure

we would use the study of the Zouave as a character type in it. Ah, if several painters agreed to collaborate

on great things.

The art of the future might be able to show us examples of that. The thing is, for the paintings

that are needed now there would have to be several of us in order to cope with the material difficulties.

Well—alas—we're not at that point—the art of painting doesn't move as fast as literature.

Like yesterday, I'm writing to you this time in great haste, really worn out. And at this moment, too,

I'm not capable of drawing; the morning in the fields has tired me out completely in that capacity.

The thing is, it's tiring, the sun down here. I'm also utterly incapable of judging my own work. I can't

see whether the studies are good or bad. I have seven studies of wheat fields, unfortunately all of them

nothing but landscapes, much against my will. Old gold yellow landscapes—done quick quick quick and

in a hurry, like the reaper who is silent under the blazing sun, concentrating on getting the job done.

I tell myself that you may perhaps—be surprised to see how little I love the Bible myself, which

I have nevertheless often tried to study a little—there is only this kernel, Christ—who, from the

point of view of art, seems superior to me—at any rate something other—than Greek, Indian,

Egyptian, Persian antiquity, which went so far. Now I say it again—this Christ is more of an artist

than the artists—he works in living spirit and flesh, he makes men instead of statues, so . . . as a

painter I feel good being an ox . . . and I admire the bull, the eagle, the man, with a veneration—

which—will prevent my being a man of ambition.

Handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 9, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 27 June 1888, Letter 9, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

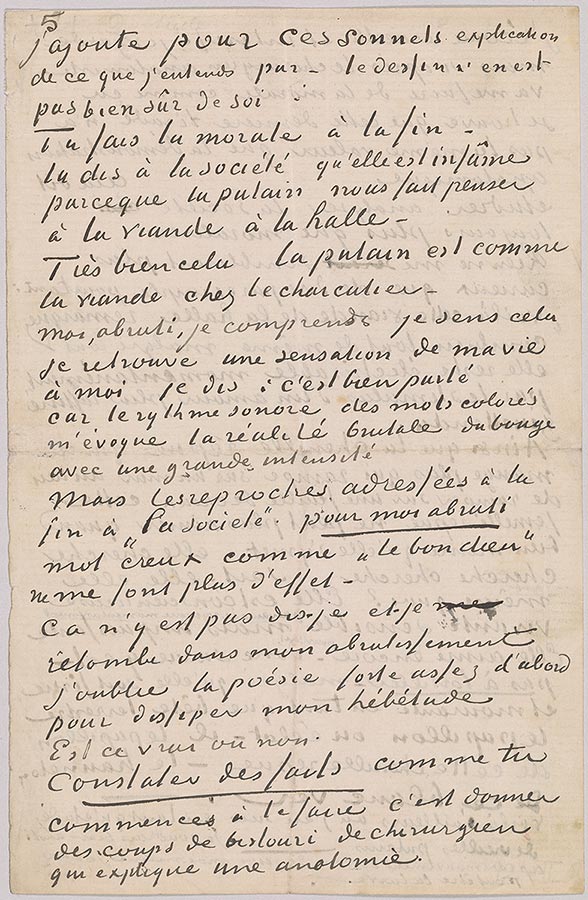

I add about these sonnets explanation of what I understand by—their design is not really sure

of itself:

You moralize at the end.

You tell society that it is squalid because the whore makes us think of meat, of the market.

Very good, that, the whore is like meat at the butcher's.

For myself—numbed—I understand, I feel that, I recognize a sensation from my own life, I

say: that's well said.

Because the sonorous rhythm of the colorful words suggests to me the brutal reality of the dive

with great intensity.

But the reproofs addressed at the end to "society." As for me, numbed, hollow words like "the

good Lord" no longer have any effect on me.

It isn't there, I say, and I sink into my numbness again; I forget the poem, at first strong enough to

dispel my lethargy.

Is that true or not?

To report the facts, as you do at the beginning, is to wield the lancet like a surgeon explaining anatomy.

>© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 9, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 27 June 1888, Letter 9, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

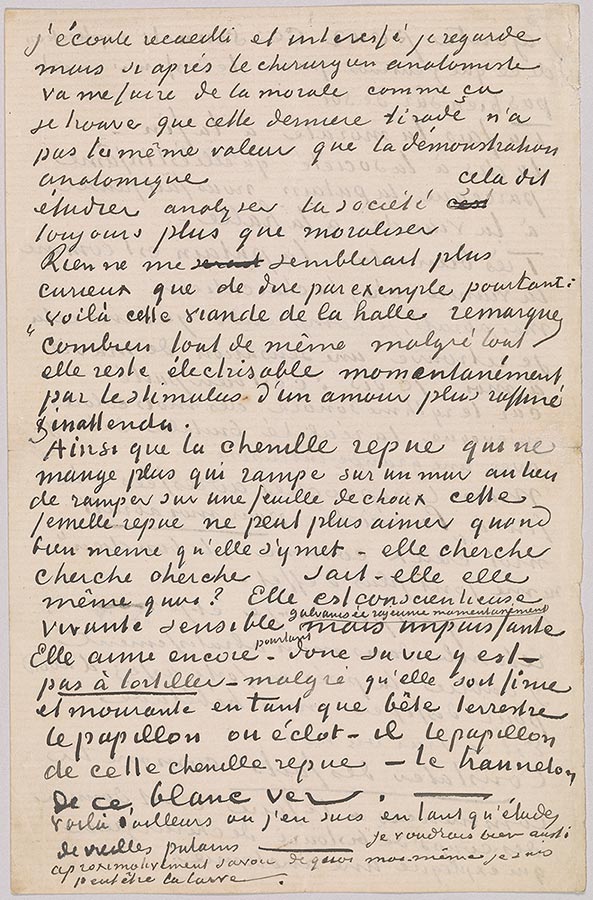

I listen, meditative and interested; I watch, but if, later, the surgeon-anatomist is going to moralize

at me like that, I find that that last tirade does not have the same value as the anatomy demonstration.

To study, to analyze society, that always says more than moralizing.

Nothing would seem more curious to me, however, than to say, for example: "see that meat from

the market, notice how, all the same, despite everything, it can still be electrified for a moment by the

stimulus of a love more refined and unexpected."

Like the sated caterpillar that no longer eats, that crawls on a wall instead of crawling on a cabbage

leaf, this sated female can no longer love, either, even though she goes about it—she seeks, seeks, seeks,

does she herself know what for? She's conscientious, alive, responsive, galvanized, rejuvenated for a

moment, but powerless. Yet she still loves—her life's there, then—make no bones about it—despite the

fact that she's finished and dying as an earthly creature. The butterfly, where does the butterfly emerge,

from that sated caterpillar—the cockchafer from that white grub?

Here, by the way, is where I am in terms of studies of old whores———I would also very much

like to know roughly what I am the larva of myself, perhaps.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

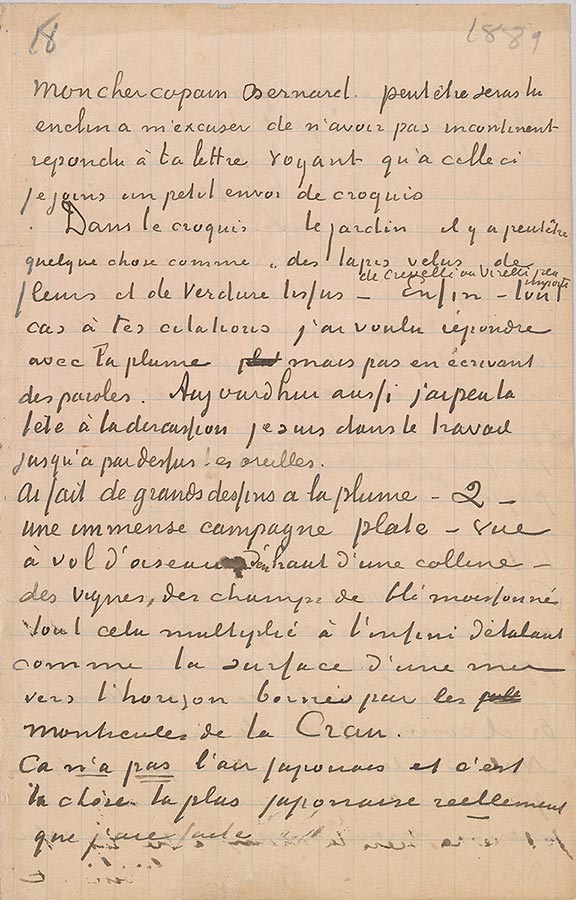

Letter 10, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 15 July 1888, Letter 10, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear old Bernard.

Perhaps you will be disposed to forgive me for not having replied to your letter straightaway, seeing

that I'm attaching a small batch of sketches to this one.

In the sketch The Garden, there is perhaps something like "the shaggy carpets of flowers and

woven greenery" of Crivelli or Virelli, doesn't much matter. Ah, well—in any case I wanted to reply

to your quotations with my pen, but not by writing words. Today, too, I don't have much of a head for

discussion; I'm up to my ears in work.

Have made large pen drawings—2—an immense flat expanse of country—seen in bird's-eye view

from the top of a hill—vineyards, reaped fields of wheat, all of it multiplied endlessly, streaming away

like the surface of a sea toward the horizon bounded by the hillocks of La Crau.

It does NOT look Japanese, and it's actually the most Japanese thing that I've done.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

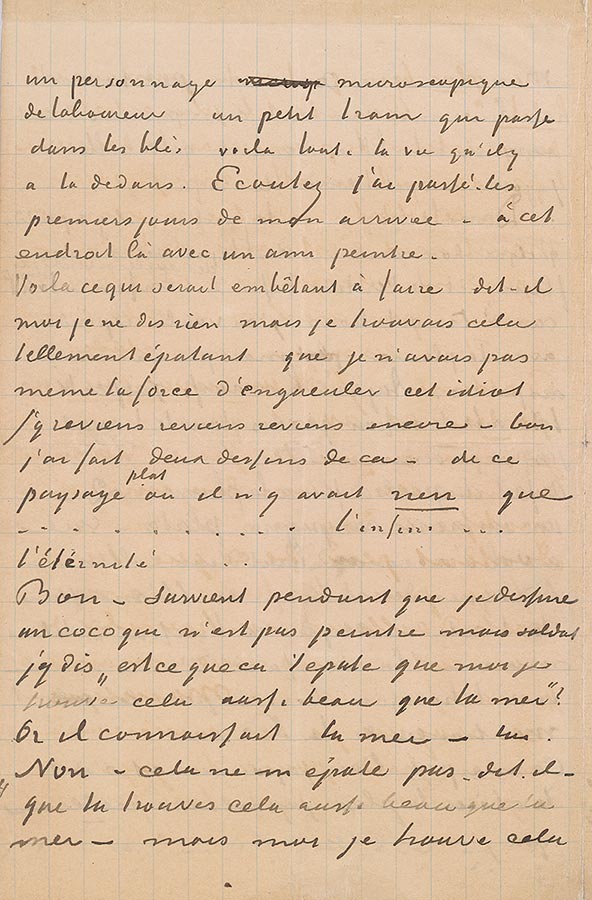

Letter 10, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 15 July 1888, Letter 10, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

A microscopic figure of a plowman, a little train passing through the wheat fields; that's the only

life there is in it. Listen, I passed—a few days after my arrival—that place with a painter friend.

There's something that would be boring to do, he said. I said nothing myself, but I found that so

astonishing that I didn't even have the strength to give that idiot a piece of my mind. I go back there,

go back, go back again—well, I've done two drawings of it—of that flat landscape in which there was

nothing but . . . the infinite . . . eternity.

Well—while I'm drawing along comes a chap who isn't a painter but a soldier. I say, "Does it

astonish you that I find that as beautiful as the sea?" Now he knew the sea—that one. "No—it doesn't

astonish me"—he says—"that you find that

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

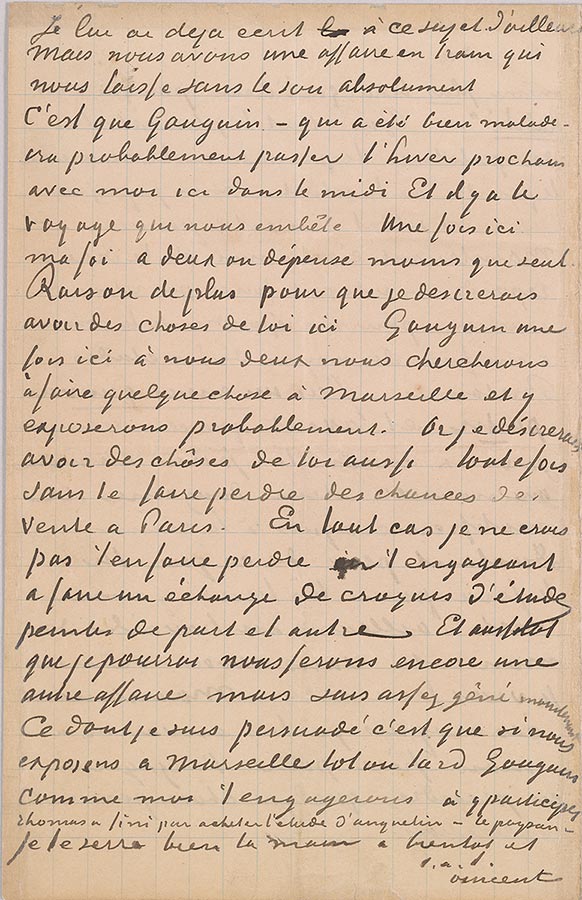

Letter 10, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 15 July 1888, Letter 10, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

as beautiful as the sea—but I find it even more beautiful

than the ocean because it's inhabited." Which of the spectators was more the artist, the first or the

second, the painter or the soldier—I myself prefer that soldier's eye. Isn't that true?

Now it's my turn to say to you, reply to me quickly this time by return of post—to let me know

if you agree to make me some sketches of your Breton studies. I have a consignment that's about to

go off, and before it clears off I want to do at least another half a dozen subjects in pen sketches for

you. Having few doubts that you will do it for yours, I'm getting down to work on my side, anyway,

without even knowing if you want to do that. Now, I'll send these sketches to my brother, to urge

him to take something from them for our collection.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 10, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 15 July 1888, Letter 10, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I've already written to him about that, anyway. But we're working on something that leaves us

absolutely without a sou.

The fact is that Gauguin—who has been very ill—is probably going to spend the coming winter

with me here in the south. And there's the fare, which is worrying us. Once here, well, two together

spend less than one alone. All the more reason why I should like to have some things by you here.

Once Gauguin's here, we'll try to do something together in Marseille, and will probably exhibit there.

Now I'd like to have some things by you, too, although without making you lose opportunities for

selling in Paris. In any case, I don't believe I'm making you lose them by encouraging you to exchange

sketches of painted studies between us. And as soon as I can, we'll do another piece of business as

well, but am quite hard up now. What I'm convinced of is that if we exhibit in Marseille, sooner or

later Gauguin and I will encourage you to join us.

Thomas bought Anquetin's study in the end—the peasant.

I shake your hand firmly, so long, and

Ever yours,

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

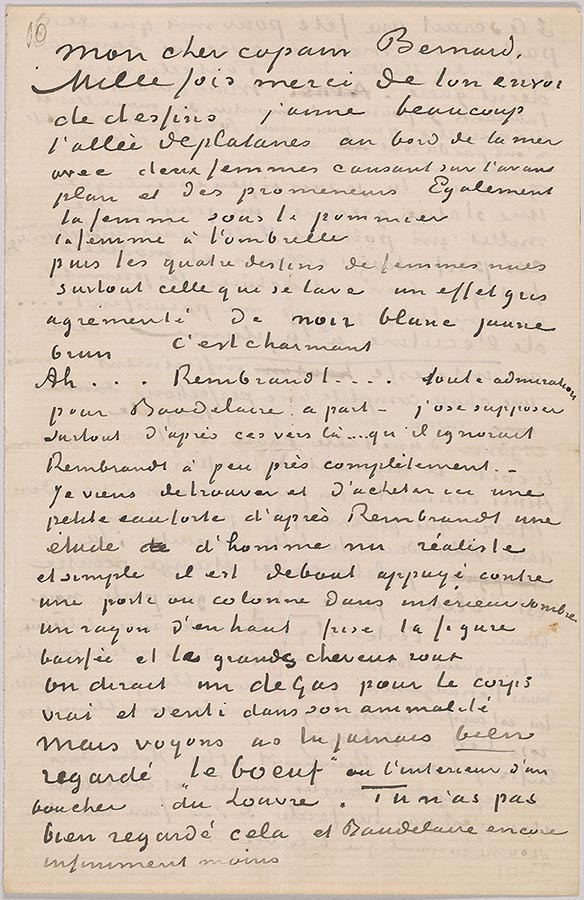

Letter 12, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 29 July 1888, Letter 12, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear old Bernard,

A thousand thanks for sending your drawings; I very much like the avenue of plane trees beside the

sea with two women chatting in the foreground and the promenaders. Also

the woman under the apple tree

the woman with the parasol

then the four drawings of nude women, especially the one washing herself, a gray effect embellished

with black, white, yellow, brown. It's charming.

Ah . . . Rembrandt . . . all admiration for Baudelaire aside—I venture to assume, especially on the

basis of those verses . . . that he knew more or less nothing about Rembrandt. I have just found and

bought here a little etching after Rembrandt, a study of a nude man, realistic and simple; he's standing,

leaning against a door or column in a dark interior. A ray of light from above skims his downturned

face and the bushy red hair.

You'd think it a Degas for the body, true and felt in its animality.

But see, have you ever looked closely at "The Ox" or the Interior of a Butcher's Shop in the Louvre?

You haven't looked closely at them, and Baudelaire infinitely less so.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

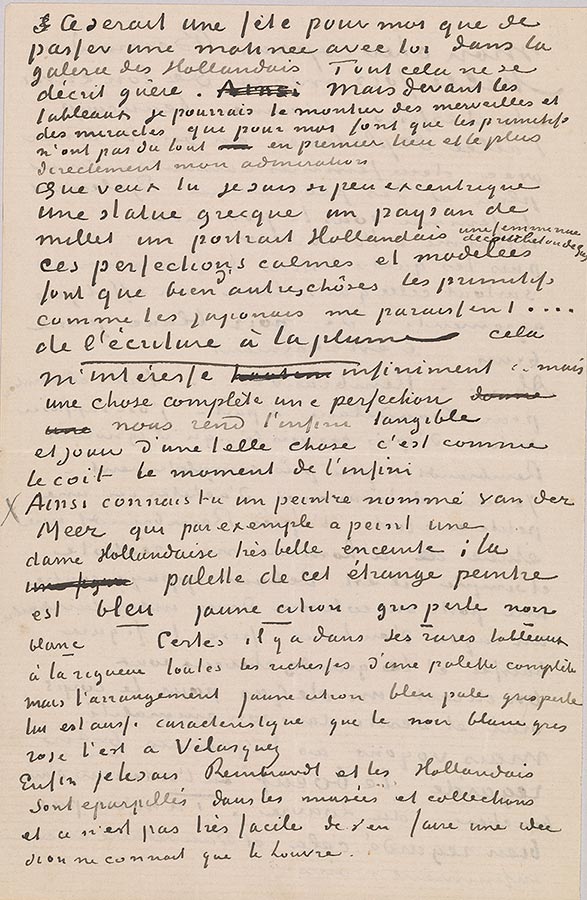

Letter 12, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 29 July 1888, Letter 12, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

It would be a treat for me to spend a morning with you in the Dutch gallery. All that is barely

describable. But in front of the paintings I could show you marvels and miracles that are the reason

that, for me, the primitives really don't have my admiration first and foremost and most directly.

But there you are; I'm so far from eccentric. A Greek statue, a peasant by Millet, a Dutch portrait, a

nude woman by Courbet or Degas, these calm and modeled perfections are the reason that many other

things, the primitives as well as the Japanese, seem to me . . . like WRITING WITH A PEN; they interest me

infinitely . . . but something complete, a perfection, makes the infinite tangible to us.

And to enjoy such a thing is like coitus, the moment of the infinite.

For instance, do you know a painter called Vermeer, who, for example, painted a very beautiful

Dutch lady, pregnant? This strange painter's palette is blue, lemon yellow, pearl gray, black, white. Of

course, in his few paintings there are, if it comes to it, all the riches of a complete palette, but the

arrangement of lemon yellow, pale blue, pearl gray is as characteristic of him as the black, white, gray,

pink is of Velázquez.

Anyway, I know, Rembrandt and the Dutch are scattered around museums and collections, and

it's not very easy to form an idea of them if you only know the Louvre.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 12, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 29 July 1888, Letter 12, page 3

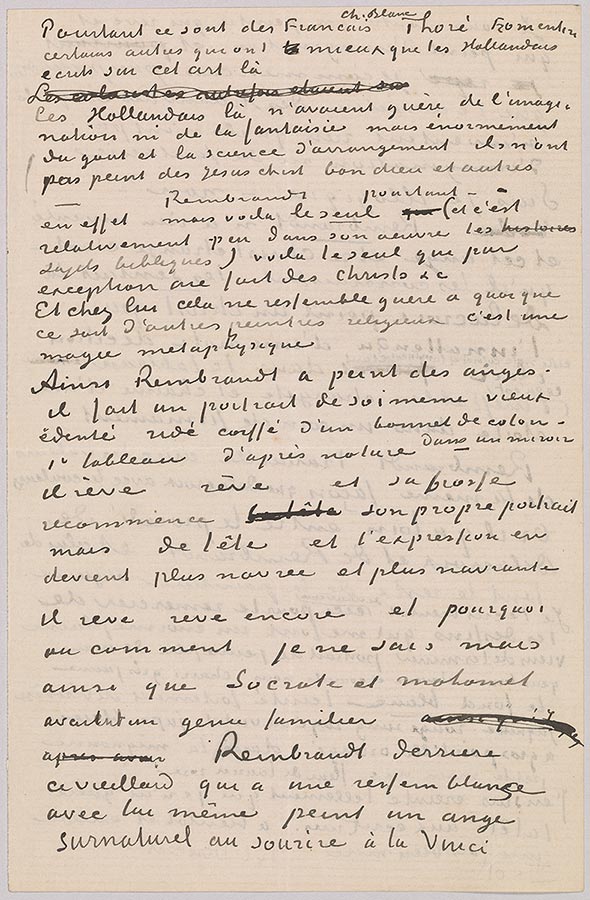

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

However, it's Frenchmen, C. Blanc, Thoré, Fromentin, certain others who have written better

than the Dutch on that art.

Those Dutchmen had scarcely any imagination or fantasy but great taste and the art of arrangement;

they did not paint Jesus Christs, the Good Lord and others. Rembrandt though—indeed, but

he's the only one (and there are relatively few biblical subjects in his oeuvre), he's the only one who,

as an exception, did Christs, etc.

And in his case, they hardly resemble anything by other religious painters; it's a metaphysical magic.

So, Rembrandt painted angels—he makes a portrait of himself as an old man, toothless, wrinkled,

wearing a cotton cap—first, painting from life in a mirror—he dreams, dreams, and his brush

begins his own portrait again, but from memory, and its expression becomes sadder and more

saddening; he dreams, dreams on, and why or how I do not know, but just as Socrates and Mohammed

had a familiar genie, Rembrandt, behind this old man who bears a resemblance to himself, paints a

supernatural angel with a da Vinci smile.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

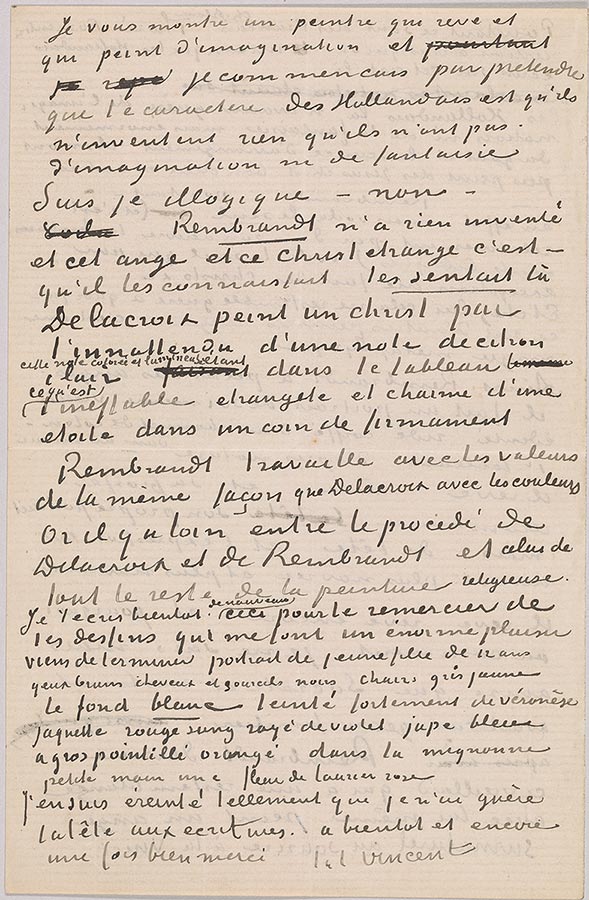

Letter 12, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 29 July 1888, Letter 12, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I'm showing you a painter who dreams and who paints from the imagination, and I started off by

claiming that the character of the Dutch is that they invent nothing, that they have neither imagination

nor fantasy.

Am I illogical? No. Rembrandt invented nothing, and that angel and that strange Christ; it's—

that he knew them, felt them there.

Delacroix paints a Christ using an unexpected light lemon note, this colorful and luminous note

in the painting being what the ineffable strangeness and charm of a star is in a corner of the firmament.

Rembrandt works with values in the same way as Delacroix with colors.

Now, there's a gulf between the method of Delacroix and Rembrandt and that of all the rest of

religious painting.

I 'll write to you again soon. This to thank you for your drawings, which give me enormous pleasure.

Have just finished portrait of young girl of twelve, brown eyes, black hair and eyebrows, flesh yellow

gray, the background white, strongly tinged with veronese, jacket blood-red with violet stripes, skirt

blue with large orange spots, an oleander flower in her sweet little hand.

I'm so worn out from it that I hardly have a head for writing. So long, and again, many thanks.

Ever yours,

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

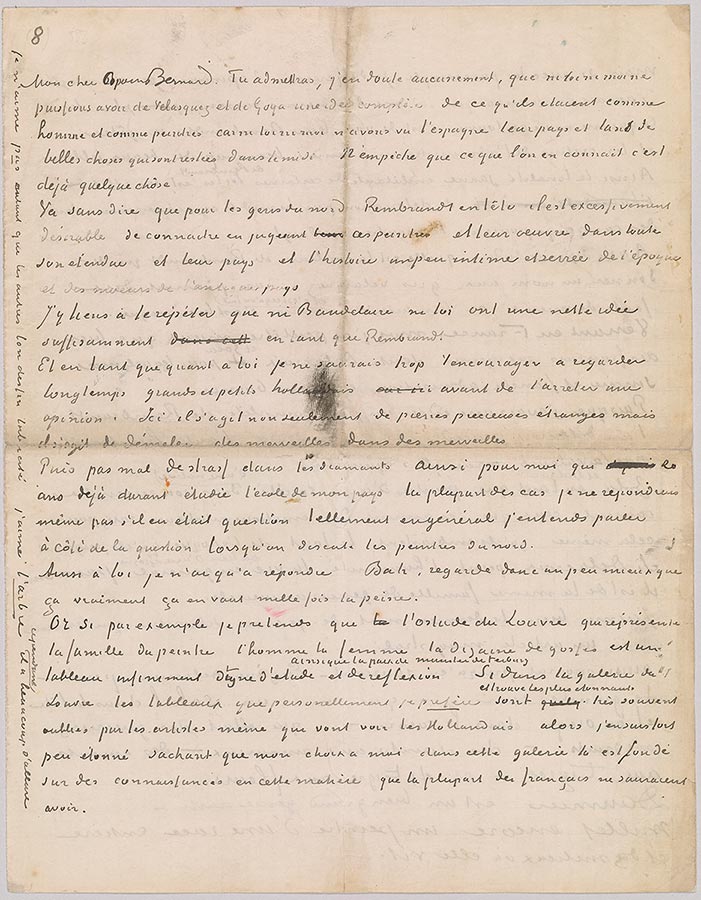

Letter 13, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 30 July 1888, Letter 13, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear old Bernard.

You'll agree, I've no doubt at all, that neither you nor I can have a full idea of what Velázquez and

Goya were like as men and as painters, because neither you nor I have seen Spain, their country,

and so many fine things that have remained in the south. Even so, what we know of them does

count for something in itself.

It goes without saying that for the northerners, Rembrandt first and foremost, it is extremely

desirable, when judging these painters, to know both their work in its full extent and their country,

and the rather intimate and hidden history of those days, and of the customs of the ancient country.

I want to repeat to you that neither Baudelaire nor you has a sufficiently clear idea when it

comes to Rembrandt.

And when it comes to you, I could not encourage you enough to take a long look at major

and minor Dutchmen before arriving at an opinion. Here it's not just a matter of strange precious

stones, but it's a matter of sorting out marvels from among marvels.

And a fair amount of paste from among the diamonds. Thus for myself, having been studying

my country's school for twenty years now, in most cases I wouldn't even reply if the subject came

up, so much do I generally hear people talk beside the point when the painters of the north are

being discussed.

So to you I can only reply, come on, just look a little more closely than that; really, it's worth

the effort a thousand times over.

Now if, for example, I claim that the van Ostade in the Louvre, which shows the painter's family,

the man, the wife, the ten or so kids, is a painting infinitely deserving of study and thought,

just like ter Borch's Peace of Münster. If the paintings in the gallery in the Louvre that I personally

prefer and find the most astonishing are very often forgotten by the very artists who go to see the

Dutchmen, then I'm not in the least surprised, knowing that my own choice in that gallery is based

on a knowledge of this subject that most of the French could not have.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

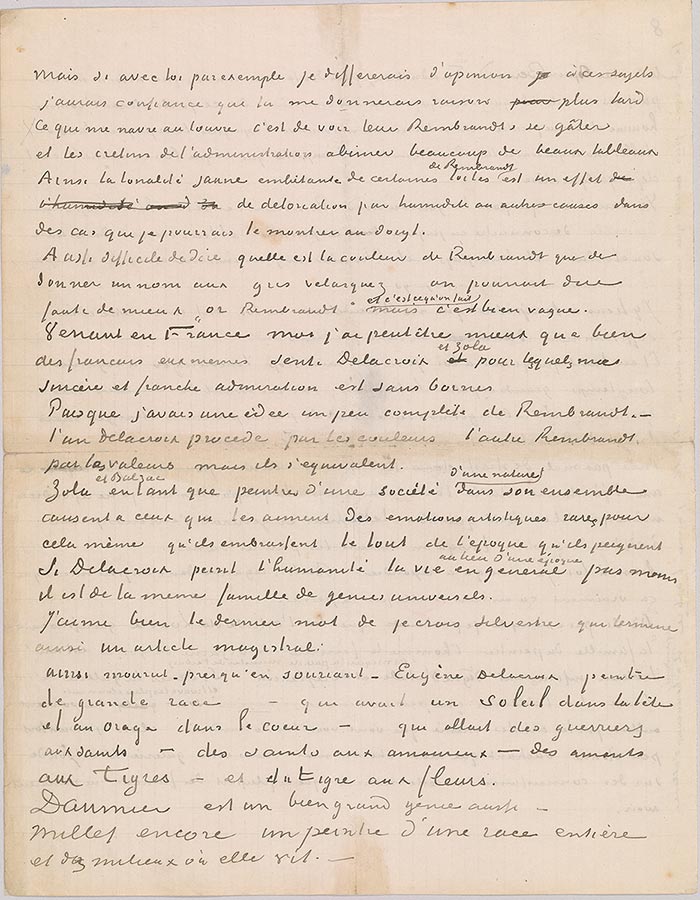

Letter 13, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 30 July 1888, Letter 13, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

But if, for example, my opinion differed from yours on those subjects, I'm confident that you

would agree with me later. What grieves me at the Louvre is to see their Rembrandts getting spoiled

and the cretins in the administration damaging many beautiful paintings. Thus the annoying yellow

tonality of certain canvases by Rembrandt is an effect of deterioration through humidity or

other causes, instances of which I could point out to you.

As difficult to say what Rembrandt's color is as to give a name to the Velázquez grays; we could

say, for want of something better, "Rembrandt gold," and that's what we do, but that's quite vague.

Having come to France I have, perhaps better than many Frenchmen themselves, felt Delacroix

and Zola, for whom my sincere and frank admiration is boundless.

Since I had a fairly complete idea of Rembrandt. One, Delacroix, proceeds by way of colors,

the other, Rembrandt, by values, but they are on a par.

Zola and Balzac, as painters of a society, of reality as a whole, arouse rare artistic emotions in

those who love them, for the very reason that they embrace the whole epoch that they paint. When

Delacroix paints humanity, life in general instead of an epoch, he belongs to the same family of

universal geniuses all the same.

I love the closing words of Silvestre, I think it was, who ends a masterly article like this:

Thus died—almost smiling—Eugène Delacroix, a painter of high breeding—who had a sun

in his head and a thunderstorm in his heart—who went from warriors to saints—from saints to

lovers—from lovers to tigers—and from the tiger to flowers.

Daumier is also a really great genius.

Millet, another painter of an entire race and the settings in which it lives.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

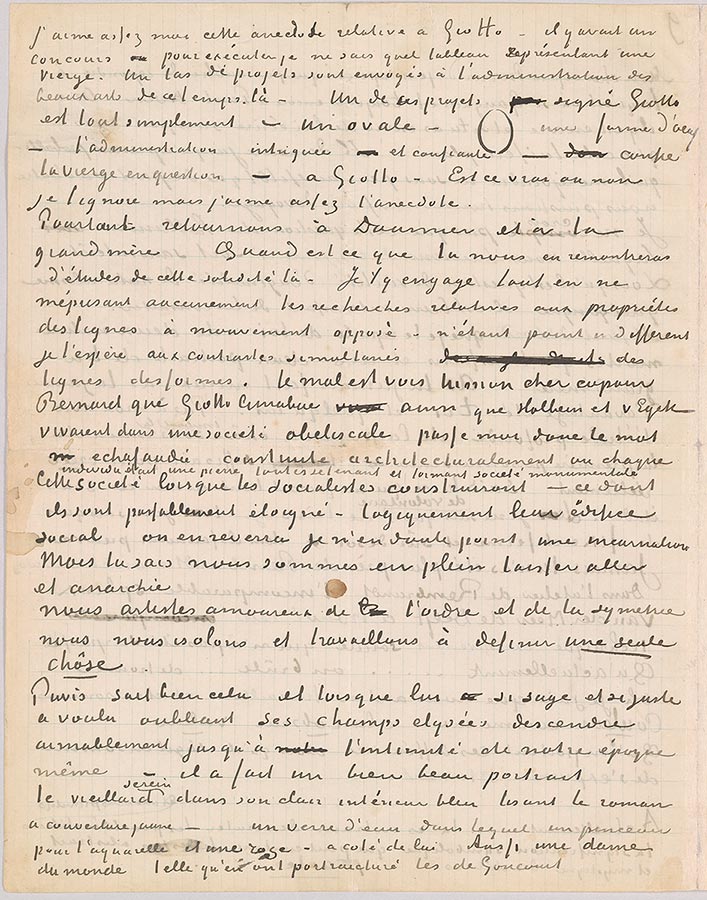

Letter 13, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 30 July 1888, Letter 13, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Possible that these great geniuses are no more than loonies, and that to have faith and boundless

admiration for them you'd have to be a loony too. That may well be—I would prefer my madness

to other people's wisdom.

To go to Rembrandt indirectly is perhaps the most direct route. Let's talk about Frans Hals.

Never did he paint Christs, annunciations to shepherds, angels or crucifixions and resurrections;

never did he paint voluptuous and bestial naked women.

He painted portraits; nothing nothing nothing but that.