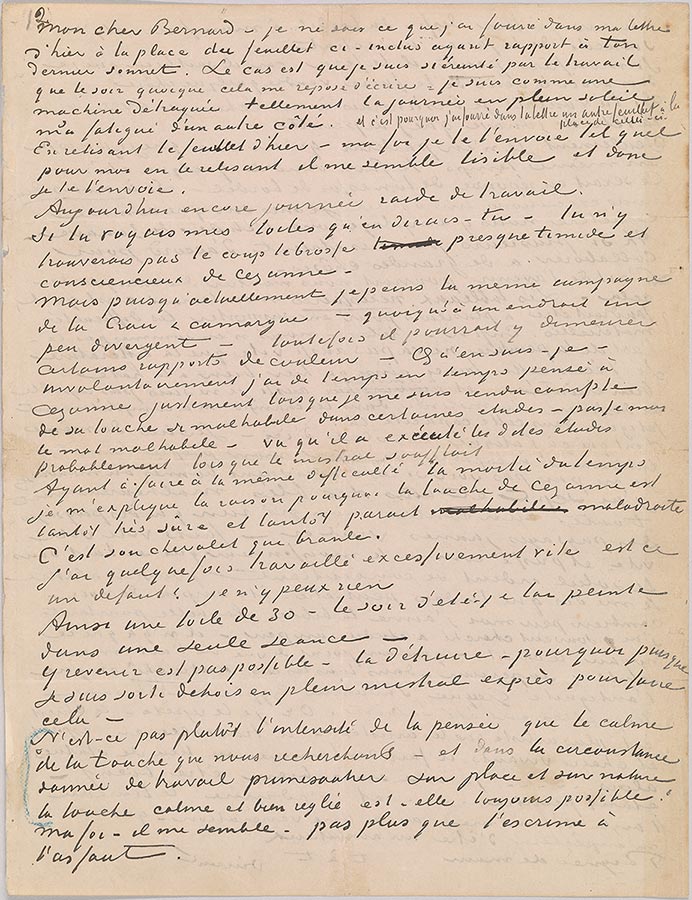

Letter 9, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 27 June 1888, Letter 9, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear Bernard—

I don't know what I stuck into my letter of yesterday instead of the enclosed sheet on the subject of

your last sonnet. The fact is that I am so worn out by work that in the evening—although writing

is restful for me—I'm like a broken-down machine, so much has the day in the full sun tired me

otherwise. And that's why I stuck another sheet into your letter instead of this one.

On rereading yesterday's sheet—well, I'm sending you it as it is; on rereading it, it seems legible

to me and so I'm sending you it.

Another hard day's work today.

If you saw my canvases, what would you say about them—you wouldn't find Cézanne's almost

diffident and conscientious brushstroke there.

But since at present I am painting the same countryside of La Crau and the Camargue—although in a slightly different place—nevertheless, certain color relationships could remain. What

do I know about it—from time to time I couldn't help thinking of Cézanne, particularly when I

realized that his touch is so clumsy in certain studies—disregard the word clumsy—seeing that he

probably executed those studies when the mistral was blowing.

Having to deal with the same difficulty half the time, I can explain why Cézanne's touch is

sometimes so sure and sometimes seems awkward. It's his easel that's wobbling.

I have sometimes worked excessively fast; is that a fault? I can't help it.

For example I've painted a no. 30 canvas—the summer evening—at a single sitting.

It's not possible to rework it; to destroy it—why, because I deliberately went outside to make it, out

in the mistral.

Isn't it rather intensity of thought than calmness of touch that we're looking for—and in the given

circumstances of impulsive work on the spot and from life, is a calm and controlled touch always possible?

Well—it seems to me—no more than fencing moves during an attack.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

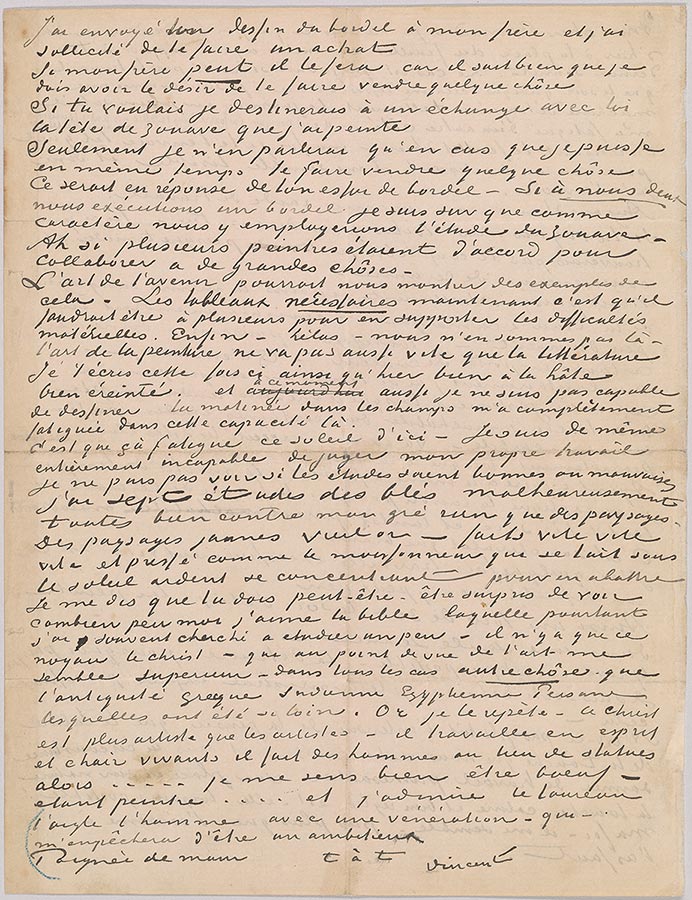

Letter 9, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 27 June 1888, Letter 9, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I have sent your drawing of the brothel to my brother, and I've asked him to buy something of yours.

If my brother can, he'll do it, because he knows very well that I must want to have you sell something.

If you wished, I would earmark for an exchange with you the head of a Zouave that I've painted.

But I won't speak about it unless I can have you sell something at the same time.

That would be in response to your attempt at a brothel. If we executed a brothel together, I'm sure

we would use the study of the Zouave as a character type in it. Ah, if several painters agreed to collaborate

on great things.

The art of the future might be able to show us examples of that. The thing is, for the paintings

that are needed now there would have to be several of us in order to cope with the material difficulties.

Well—alas—we're not at that point—the art of painting doesn't move as fast as literature.

Like yesterday, I'm writing to you this time in great haste, really worn out. And at this moment, too,

I'm not capable of drawing; the morning in the fields has tired me out completely in that capacity.

The thing is, it's tiring, the sun down here. I'm also utterly incapable of judging my own work. I can't

see whether the studies are good or bad. I have seven studies of wheat fields, unfortunately all of them

nothing but landscapes, much against my will. Old gold yellow landscapes—done quick quick quick and

in a hurry, like the reaper who is silent under the blazing sun, concentrating on getting the job done.

I tell myself that you may perhaps—be surprised to see how little I love the Bible myself, which

I have nevertheless often tried to study a little—there is only this kernel, Christ—who, from the

point of view of art, seems superior to me—at any rate something other—than Greek, Indian,

Egyptian, Persian antiquity, which went so far. Now I say it again—this Christ is more of an artist

than the artists—he works in living spirit and flesh, he makes men instead of statues, so . . . as a

painter I feel good being an ox . . . and I admire the bull, the eagle, the man, with a veneration—

which—will prevent my being a man of ambition.

Handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

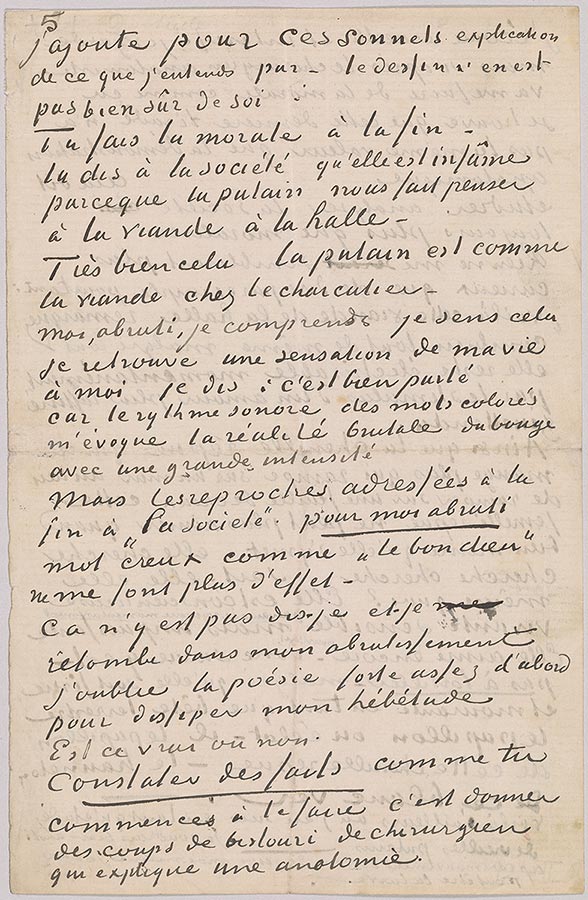

Letter 9, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 27 June 1888, Letter 9, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I add about these sonnets explanation of what I understand by—their design is not really sure

of itself:

You moralize at the end.

You tell society that it is squalid because the whore makes us think of meat, of the market.

Very good, that, the whore is like meat at the butcher's.

For myself—numbed—I understand, I feel that, I recognize a sensation from my own life, I

say: that's well said.

Because the sonorous rhythm of the colorful words suggests to me the brutal reality of the dive

with great intensity.

But the reproofs addressed at the end to "society." As for me, numbed, hollow words like "the

good Lord" no longer have any effect on me.

It isn't there, I say, and I sink into my numbness again; I forget the poem, at first strong enough to

dispel my lethargy.

Is that true or not?

To report the facts, as you do at the beginning, is to wield the lancet like a surgeon explaining anatomy.

>© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

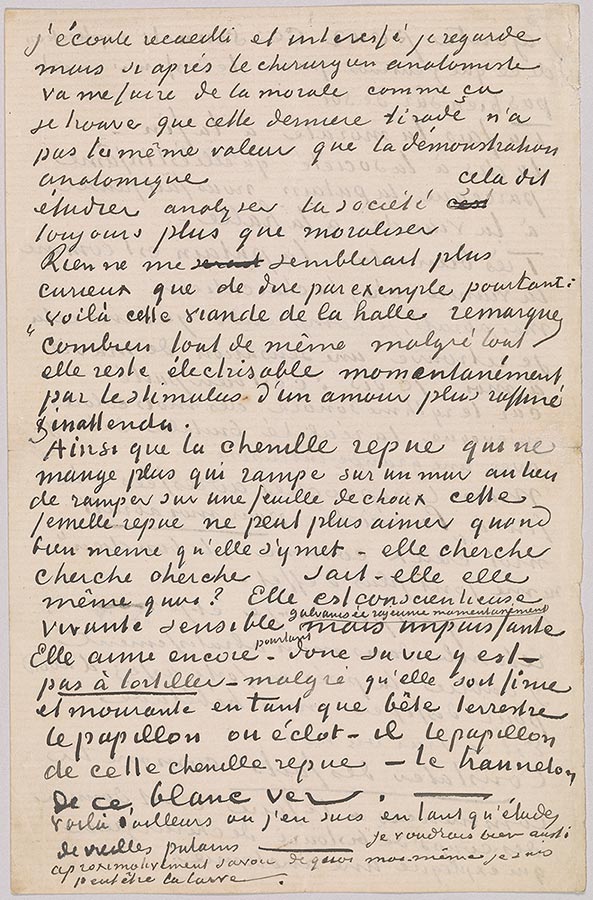

Letter 9, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 27 June 1888, Letter 9, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I listen, meditative and interested; I watch, but if, later, the surgeon-anatomist is going to moralize

at me like that, I find that that last tirade does not have the same value as the anatomy demonstration.

To study, to analyze society, that always says more than moralizing.

Nothing would seem more curious to me, however, than to say, for example: "see that meat from

the market, notice how, all the same, despite everything, it can still be electrified for a moment by the

stimulus of a love more refined and unexpected."

Like the sated caterpillar that no longer eats, that crawls on a wall instead of crawling on a cabbage

leaf, this sated female can no longer love, either, even though she goes about it—she seeks, seeks, seeks,

does she herself know what for? She's conscientious, alive, responsive, galvanized, rejuvenated for a

moment, but powerless. Yet she still loves—her life's there, then—make no bones about it—despite the

fact that she's finished and dying as an earthly creature. The butterfly, where does the butterfly emerge,

from that sated caterpillar—the cockchafer from that white grub?

Here, by the way, is where I am in terms of studies of old whores———I would also very much

like to know roughly what I am the larva of myself, perhaps.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam