Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio (1508–1580)

I quattro libri dell'architettura (Four Books on Architecture)

Printed by Dominico de' Franceschi in Venice, 1570

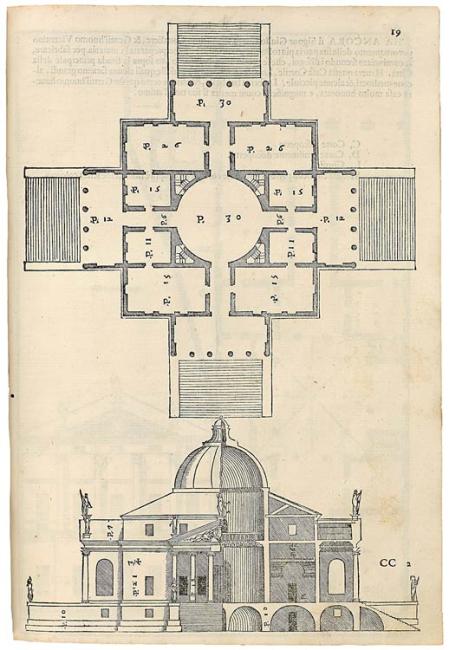

Opening: Plan and Elevation of Villa La Rotonda

Gift of Paul Mellon, 1979

PML 76057

The architect Andrea Palladio's literary masterwork, the treatise I quattro libri dell'architettura, begun in 1555, profoundly influenced Western architecture.

This illustration presents a plan and an elevation of Palladio's Villa La Rotonda, just outside Vicenza. The design is for a completely symmetrical building with a square plan around a central circular hall with a dome. Each of the four facades has a portico.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

Aristotle

Aristotle

Opera (Works)

Printed on vellum by Andrea Torresanus and Bartolomeo de Blavis in Venice, 1483

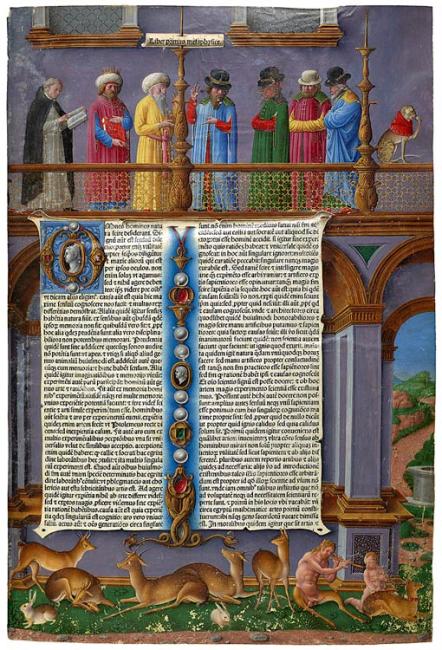

Opening, Volume 1: Aristotle and Averroes Disputing by Girolamo da Cremona

Purchased in 1919

PML 21194-95

This luxurious two-volume edition of the works of Aristotle was called by Henry Yates Thompson "the most magnificent book in the world." The trompe-l'oeil tendencies already evident in Girolamo da Cremona's Augustine of 1475 have been developed even further in the two frontispieces of this copy. In the first volume, the vellum of the page appears to have been torn away to reveal Aristotle conversing with a turbaned figure, possibly the Cordovan commentator Averroës (1126–1190). Beneath is a richly decorated architectural façade set into a landscape populated with satyrs, putti, and deer. A Latin inscription on the façade states that one Petrus Ulmer "brought this Aristotle to the world." Some scholars have identified this figure with Peter Ugelheimer, a Frankfurt bookseller resident in Venice who sold to Torresanus the punches of the celebrated printer Nicolas Jenson.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

Aristotle

Aristotle

Opera (Works)

Printed on vellum by Andrea Torresanus and Bartolomeo de Blavis in Venice, 1483

Opening, Volume 2: Group of Philosophers Disputing by Girolamo da Cremona

Purchased in 1919

PML 21194-95

The text of Aristotle's Metaphysics is embellished by a group of disputing philosophers, including at far left a Dominican (probably Thomas Aquinas) and again Averroes (third from left).

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

Attributed to Francesco Colonna

Attributed to Francesco Colonna

(1433–1527)

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Poliphilo's Strife of Love in a Dream)

Printed by Aldus Manutius in Venice, 1499

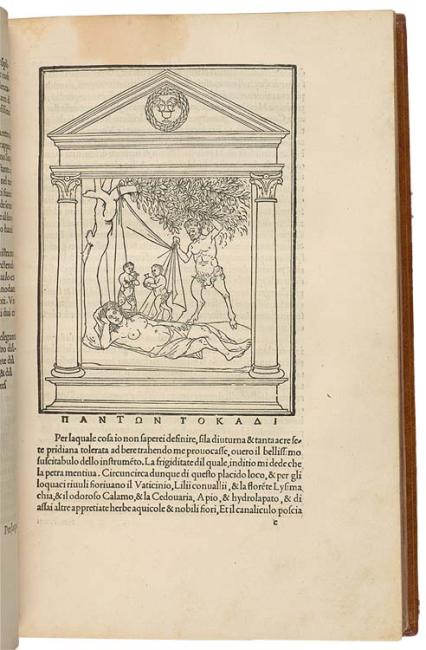

Opening: Nymph Discovered by a Satyr

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan with the library of Theodore Irwin, 1900

PML 373

Because of its elegant page layout, roman typeface, and refined woodcut illustrations, this famous example of early printing has been called the most beautiful illustrated book printed in Italy in the fifteenth century. The woodcuts are thought to have been designed by Benedetto Bordone, a successful miniaturist who turned to new artistic activities in the age of printing.

Written as an allegorical romance, the Hypnerotomachia tells of Poliphilo, who pursues his love, Polia, through a dreamlike landscape. The nymph discovered by a satyr shown here is thought to have inspired Giorgione's painting of around 1510, Venus Reclining (Dresden), considered the first painting of a female nude since antiquity.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

Biblia

Biblia

Translated into Italian by Niccolò Malermi.

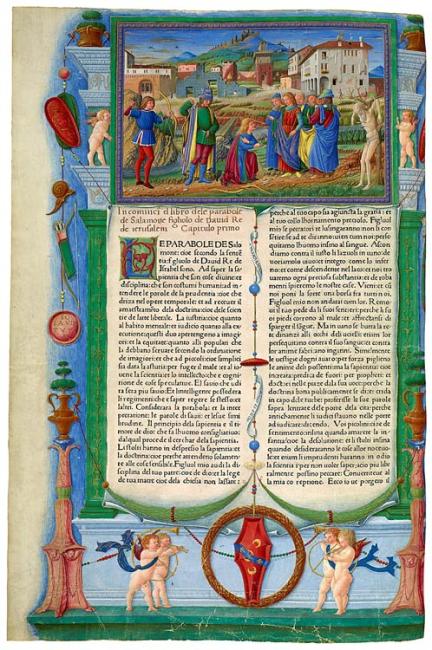

Opening, Volume 2: Shooting of the Father's Corpse

Printed on vellum by Vindelinus de Spira in Venice 1 August 1471

Purchased in 1929 PML 26984

This is the frontispiece to the second volume of the 1471 bible. The text appears to have been printed on a frayed piece of parchment suspended from an architectural monument—one of the most ambitious pictorial illusions in a Venetian book created during the Renaissance.

The framed picture at top illustrates the Shooting of the Father's Corpse, one of the apocryphal judgments of Solomon. In an inheritance dispute between the true son of a recently deceased man and an impostor, the actual son kneels before the suspended corpse, while the impostor reveals his counterfeit status by following King Solomon's command to shoot at the corpse.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

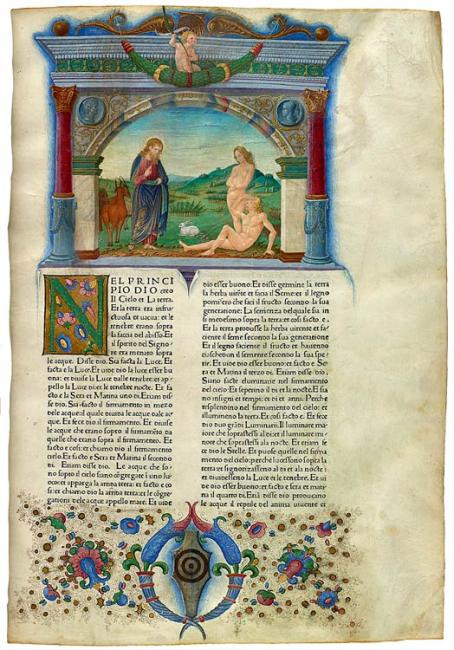

Biblia

Biblia

Printed on vellum by Vindelinus de Spira in Venice, 1 August 1471

Translated into Italian by Niccolò Malermi.

Opening, Volume 1: Creation of Eve

Purchased in 1929 PML 26983

Item description:

Professional illuminators supplied borders and initials for some of the first books printed in Venice, a center of the book trade with an affluent clientele prepared to pay handsomely for special copies decorated no less lavishly than the illuminated manuscripts of the day. An anonymous miniaturist known as the Master of the Putti produced this stunning trompe l'oeil frontispiece for the second volume of the Malermi Bible, the first edition of the Bible translated into Italian. In the framed miniature, Solomon reveals the rightful heir to an estate by having him and his heartless brothers shoot at their father's corpse, a task beyond the powers of a truly devoted son.

Most bibles were written or published in Latin. This copy, printed by Vindelinus de Spira, is in Italian. It is one of the earliest bibles published in the vernacular.

Gold highlights in The Creation of Eve, shown at the top of the page, create the impression of a sun-drenched landscape. Although the miniatures in both volumes of this bible may be attributed to the Master of the Putti, the two books originally may not have belonged together. This one may have belonged to the Cornaro family of Venice (their shield is covered by a later coat of arms), whereas the second volume displays the arms of the Macigni family.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

Cesare Vecellio

Cesare Vecellio

(1521–1601)

Degli habiti, antichi et moderni di diversi parti del mondo (Of Costumes, Ancient and Modern, of Different Parts of the World)

Printed by Damian Zenaro in Venice, 1590

Opening: Woman Blonding Her Hair

Purchased with the Toovey Collection, 1899

PML 9626

Vecellio initially joined the workshop of his famous cousin Titian, but by 1570 was primarily active as a publisher. This book contains woodcut illustrations of costumes—exotic and domestic—and marks the culmination of a trend that began with the increase in travel during the mid-sixteenth century. Highly popular, this most famous example of costume books became a model of the genre.

The woman shown here is assiduously trying to make her hair a lighter shade of blonde with the help of different liquids. Her pianelle, high platform shoes, stand nearby.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

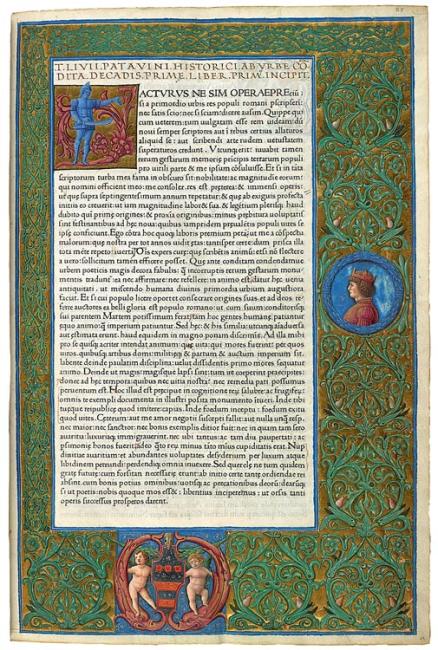

Livy (Titus Livius Patavinus)

Livy (Titus Livius Patavinus)

Historiae romanae decades (Roman History)

Opening: Illuminated Page with the Coat of Arms of the Venetian Donà Family

1470

Printed on vellum by Vindelinus de Spira in Venice

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan with the library of Theodore Irwin, 1900

PML 266

Livy's Historiae romanae decades was one of the first classical Latin texts to be printed in Venice. The book and chapter headings, at the top in gold, were added by a trained scribe. Woodcut patterns that served to guide the miniaturist were stamped into the margins after printing and appear underneath the intense green vine motifs contrasting with gold ground of the painted borders. The blue soldier in Roman armor with an outstretched arm represents the letter F, thus providing the initial for the first word on the page, Facturus.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

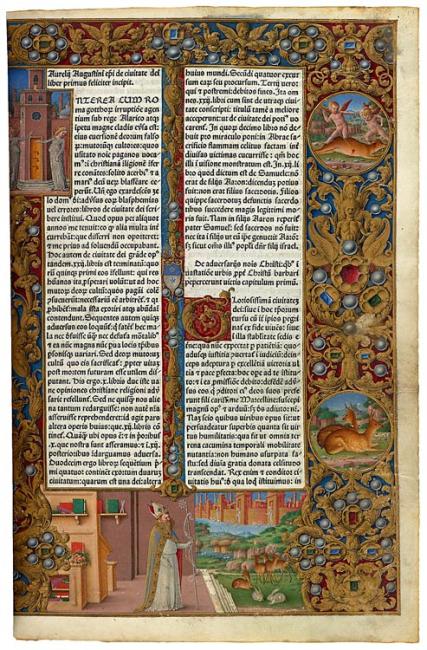

St. Augustine

St. Augustine

De civitate dei

Venice: Nicolas Jenson, 2 October 1475

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan with the library of Theodore Irwin, 1900

PML 310

Many magnificent books were printed in Venice. This copy of De civitate Dei left the printing press without initials and decorative borders, which were added by hand—probably by Girolamo da Cremona. The lavish frontispiece depicts St. Augustine standing to the side of his scholarly study before a distant landscape. The Heavenly City of his vision, with angelic guardians standing at the gates, floats in the distance. Clearly a luxury item, this book was printed on vellum. Set unobtrusively, near the center of the page, is the blue-and-white coat of arms of the Mocenigo family. Pietro Mocenigo was doge of Venice from 1474 to 1476; the volume probably once belonged to him.

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility. The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.