Renaissance Venice: Drawings from the Morgan

At the dawn of the sixteenth century, the republic of Venice emerged as a critical hub for international trade and a thriving artistic center. Patronage from the oligarchic government, church communities, lay confraternities, and wealthy individuals fostered intense creative activity. The innovations of celebrated masters, including Vittore Carpaccio, Titian, Paris Bordone, Jacopo Tintoretto, and Paolo Veronese, had a profound influence on art in Venice and its territories as well as on the works of such foreign visitors as Albrecht Dürer.

This selection of exceptional works from the Morgan's collection chronicles a remarkable period of artistic creativity in Venice. Covering a wide range of subjects—including landscape, portraiture, religious and civic life, technical innovations, and the role of foreign artists—the drawings, maps, and books presented here offer a fresh look at this seminal moment in history and art.

This online exhibition is presented in conjunction with the exhibition Renaissance Venice: Drawings from the Morgan (May 18-December 23, 2012), organized by guest curator Rhoda Eitel-Porter. It is based on research by Rhoda Eitel-Porter and Laura B. Zukerman.

Major funding for this exhibition is provided by the Alex Gordon Fund for Exhibitions.

Generous support is provided by The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation and by Robert B. Loper, with additional assistance from members of the Visiting Committee to the Department of Drawings and Prints.

Paolo Veronese (1528–1588)

Studies for The Finding of Moses, ca. 1580

Pen and brown ink, brown wash

6 3/4 x 7 3/8 inches (171 x 186 mm.)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909; IV, 81

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

Vittore Carpaccio

Sacra Conversazione

Gift of the Thaw Collection, 2006

This drawing is a late compositional study for Carpaccio's panel painting of the Virgin and Child with Four Saints in the Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon. The Virgin and Christ Child with Saint John the Baptist and two female saints are set against a complex landscape background inhabited by three hermit saints. At center left, Augustine speaks to the small child; Jerome stands on the rocky arch; and Anthony Abbot sits just inside a small hut surmounted by a cross.

This is Carpaccio's compositional study for a panel painting of about 1500–1512 (Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon). The complex and somewhat bizarre landscape provides the setting for three hermit saints: Augustine, Jerome, and one generally identified as Anthony Abbot, all of whom are described with Carpaccio's typical anecdotal detail. The drawing is one of the earliest in European art to integrate figures into a finished landscape.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

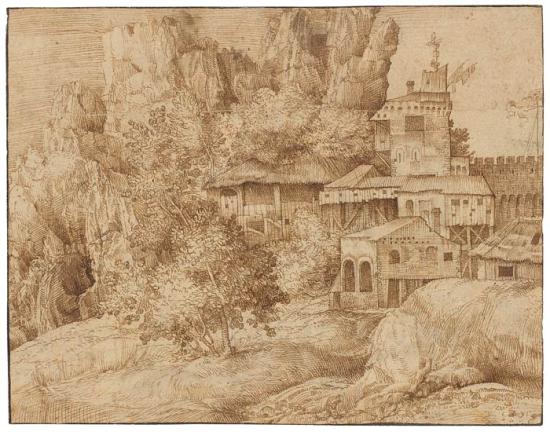

Giulio Campagnola

Buildings in a Rocky Landscape

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Engraver and draftsman Giulio Campagnola arrived in Venice in 1507, where he worked in the entourage of Giorgione. Campagnola and his adopted son, Domenico, introduced a new specialty into Venetian art—the pure, narrative-free landscape. Their large, panoramic landscapes created with flowing rhythmic strokes informed succeeding generations, including Pieter Bruegel, Goltzius, and Rubens, and were much sought after by cultivated collectors.

The dense cross-hatching and extreme delicacy with which the artist rendered the picturesque cluster of buildings suggest the influence of both Albrecht Dürer and Giorgione.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

Titian

Landscape with St. Theodore Overcoming the Dragon

Inscribed on old mount at center, beneath the drawing, in pen and brown ink, Titiano da Cadore.

Gift of János Scholz, 1977

Arguably the greatest of all Venetian painters, Titian was held in high esteem during his lifetime. His paintings and drawings were as novel in subject matter and composition as they were bold in technique. St. Theodore Overcoming the Dragon is one of the rare landscape drawings attributed to the artist.

Theodore, one of the patron saints of Venice, did not slay the dragon but instead made it roll over in submission. The figure seated under the tree in the background may be the mother who, according to legend, brought her ailing child to be bathed in a miraculous well guarded by the dragon.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

Girolamo Romanino

Pastoral Concert with Two Women, a Faun and a Soldier

Gift of Janos Scholz, 1973

To complete his education and attracted by the innovations of Giorgione, Romanino went to Venice, where Albrecht Dürer's Feast of the Rose Garlands and paintings by Giorgione and Titian proved to be a lasting influence on his work.

Following a tradition founded by Titian and Giorgione, the theme of music intermingled with love in a pastoral landscape became popular in northern Italy in the early sixteenth century. This is one of three drawings by Romanino of musical groups with a faun, which are usually associated with frescoes the artist painted in Trent around 1531–32.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

Paris Bordone

Standing Man Playing a Viola da Gamba (Violoncello)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

The present figure is inspired by a similar portrayal of a musician in a pen-and-ink drawing of a pastoral concert by Titian, to whom Bordone was briefly apprenticed.

Whereas Titian's figure is using the bow to point in the general direction of the area circumscribed by the legs of his seated female companion, Bordone's more autonomous figure is playing the instrument. The composition anticipates the poetic depictions of mythological subjects that became popular in the mid-sixteenth century.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

Patronage

The astonishing creative efflorescence of sixteenth-century Venice would not have been possible without a rich network of civic, religious, and governmental support. The republic was governed by a hereditary ruling class under the leadership of a doge—generally a member of the inner circle of powerful local families whom the aristocracy appointed for life. Venice celebrated itself and proclaimed its civic ideals in large paintings by Titian, Veronese, and Federico Zuccaro that lined the walls of the Doge's Palace. Wealthy lay confraternities, called scuole, provided another essential layer of support and promoted a distinctively Venetian style of large narrative composition. Finally, a powerful and enlightened aristocracy commissioned works for their private dwellings in town and on the mainland. Whereas Giovanni Bellini and his followers had primarily produced altarpieces and religious images for personal devotion, this new generation of Venetian artists also met the demands of their expanding clientele for secular subject matter.

Bartolomeo Montagna

Drunkenness of Noah

Inscribed at lower right, in pen and brown ink, albordür[er] [i.e., Alberto Dürer].

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Patronage

The astonishing creative efflorescence of sixteenth-century Venice would not have been possible without a rich network of civic, religious, and governmental support. The republic was governed by a hereditary ruling class under the leadership of a doge—generally a member of the inner circle of powerful local families whom the aristocracy appointed for life. Venice celebrated itself and proclaimed its civic ideals in large paintings by Titian, Veronese, and Federico Zuccaro that lined the walls of the Doge's Palace. Wealthy lay confraternities, called scuole, provided another essential layer of support and promoted a distinctively Venetian style of large narrative composition. Finally, a powerful and enlightened aristocracy commissioned works for their private dwellings in town and on the mainland. Whereas Giovanni Bellini and his followers had primarily produced altarpieces and religious images for personal devotion, this new generation of Venetian artists also met the demands of their expanding clientele for secular subject matter.

The painter and architect Bartolomeo Montagna, who is first documented in Venice in 1469, was a member of Giovanni Bellini's workshop. In the present sheet, one of Noah's sons is shown piously attempting to cover his drunken father's nudity, while another draws attention to this embarrassing state. The drawing has been associated with a commission of 1482 for the Scuola Grande di San Marco, Venice, for paintings of the flood and "other related events" from the Book of Genesis. The paintings were destroyed in a fire in 1485.

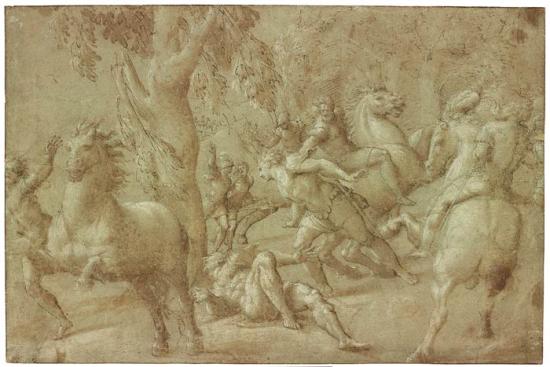

Giovanni Antonio Pordenone

Conversion of St. Paul, early 1530s

Gift of J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1924

This drawing is the modello for a well-known painting by Pordenone, now lost, that must have impressed critics and artists alike through the virtuosity of its radically foreshortened figures and its splendid sense of movement and energy. It spawned several copies, Pordenone repeated sections of it for Venetian collectors, and Tintoretto used it as inspiration for a painting of the same subject (National Gallery of Art, Washington).

Pordenone's composition adapted elements from a tapestry cartoon of the same subject by Raphael, which was displayed in the house of Cardinal Domenico Grimani in Venice.

Patronage

The astonishing creative efflorescence of sixteenth-century Venice would not have been possible without a rich network of civic, religious, and governmental support. The republic was governed by a hereditary ruling class under the leadership of a doge—generally a member of the inner circle of powerful local families whom the aristocracy appointed for life. Venice celebrated itself and proclaimed its civic ideals in large paintings by Titian, Veronese, and Federico Zuccaro that lined the walls of the Doge's Palace. Wealthy lay confraternities, called scuole, provided another essential layer of support and promoted a distinctively Venetian style of large narrative composition. Finally, a powerful and enlightened aristocracy commissioned works for their private dwellings in town and on the mainland. Whereas Giovanni Bellini and his followers had primarily produced altarpieces and religious images for personal devotion, this new generation of Venetian artists also met the demands of their expanding clientele for secular subject matter.

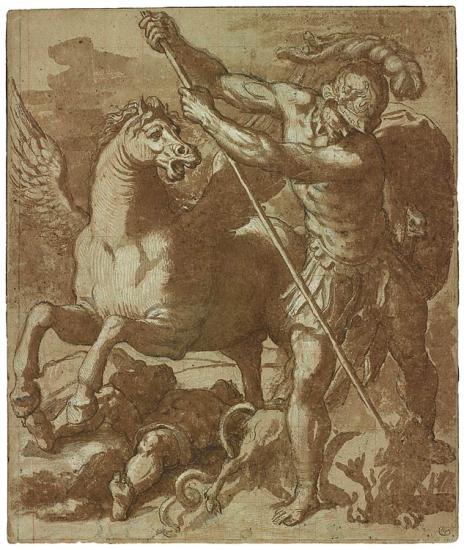

Giuseppe Porta, called Salviati

Bellerophon Killing the Chimera

Gift of Janos Scholz, 1973

Porta left Rome with his master, Francesco Salviati—whose name he later assumed—and arrived in Venice in July 1539. In that year he executed his most important commission in fresco, an ambitious ceiling for the Sala dell'Anticollegio in the Palazzo Ducale, which was destroyed by fire in 1574. Although he did not develop a pronounced individual style, Porta is partially responsible for bringing central Italian Mannerism to Venice.

This drawing is thought to be the study for a lost fresco painted on the facade of Nicolo Bernardo's house in Campo di San Polo, Venice.

Patronage

The astonishing creative efflorescence of sixteenth-century Venice would not have been possible without a rich network of civic, religious, and governmental support. The republic was governed by a hereditary ruling class under the leadership of a doge—generally a member of the inner circle of powerful local families whom the aristocracy appointed for life. Venice celebrated itself and proclaimed its civic ideals in large paintings by Titian, Veronese, and Federico Zuccaro that lined the walls of the Doge's Palace. Wealthy lay confraternities, called scuole, provided another essential layer of support and promoted a distinctively Venetian style of large narrative composition. Finally, a powerful and enlightened aristocracy commissioned works for their private dwellings in town and on the mainland. Whereas Giovanni Bellini and his followers had primarily produced altarpieces and religious images for personal devotion, this new generation of Venetian artists also met the demands of their expanding clientele for secular subject matter.

Paolo Veronese

Group of Figures for a Ceiling Decoration

Inscribed at lower right, in pen and brown ink, di Paolo V.

Purchased as the gift of the Fellows with the special assistance of Mrs. Gerrit P. Van de Bovenkamp, 1981

Veronese's secular history paintings fall into two groups: his state commissions for the Ducal Palace and St. Mark's Library, and his decoration of villas and palaces belonging to Venetian nobility. His greatest accomplishment of the first group is the Triumph of Venice in the Sala del Maggior Consiglio. At the left of this exploratory sketch for the project, the figure of Venice is being crowned by Victory.

Veronese frequently used chalk after arriving in Venice in 1553, although pen and ink remained his preferred medium.

Patronage

The astonishing creative efflorescence of sixteenth-century Venice would not have been possible without a rich network of civic, religious, and governmental support. The republic was governed by a hereditary ruling class under the leadership of a doge—generally a member of the inner circle of powerful local families whom the aristocracy appointed for life. Venice celebrated itself and proclaimed its civic ideals in large paintings by Titian, Veronese, and Federico Zuccaro that lined the walls of the Doge's Palace. Wealthy lay confraternities, called scuole, provided another essential layer of support and promoted a distinctively Venetian style of large narrative composition. Finally, a powerful and enlightened aristocracy commissioned works for their private dwellings in town and on the mainland. Whereas Giovanni Bellini and his followers had primarily produced altarpieces and religious images for personal devotion, this new generation of Venetian artists also met the demands of their expanding clientele for secular subject matter.

Portraiture

Inspired by earlier northern European models, Venetian artists of the sixteenth century approached portraiture with a new naturalism. Portraits of individuals were commissioned to document physical likeness as well as social status, often conveyed through opulent clothing and lavish settings. Initially, most sitters were portrayed in strict profile, much like the depictions on ancient coins. Later, evocative three-quarter or frontal views dominated, inviting a more direct and intimate relationship with the viewer. In Venice and northern Italy, group portraits became fashionable. The artist Palma Giovane, for example, produced numerous quick sketches of his large family and wide circle of friends. Through the work of such artists as Carpaccio, Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, Venice established a remarkable portraiture tradition.

Vittore Carpaccio

Head of Bearded Man Wearing a Cap, in Profile to the Left

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Carpaccio's large narrative scenes made for Venetian scuole—lay confraternities run by merchants and citizens excluded from politics because they were not of noble blood—often included likenesses of the institution's dignitaries. This drawing has been associated with the artist's Life of Saint Ursula cycle (Accademia, Venice), although no equivalent figure appears in those paintings.

The typically Venetian technique of brush drawing on blue paper became highly advanced in the hands of Gentile Bellini and Carpaccio.

Portraiture

Inspired by earlier northern European models, Venetian artists of the sixteenth century approached portraiture with a new naturalism. Portraits of individuals were commissioned to document physical likeness as well as social status, often conveyed through opulent clothing and lavish settings. Initially, most sitters were portrayed in strict profile, much like the depictions on ancient coins. Later, evocative three-quarter or frontal views dominated, inviting a more direct and intimate relationship with the viewer. In Venice and northern Italy, group portraits became fashionable. The artist Palma Giovane, for example, produced numerous quick sketches of his large family and wide circle of friends. Through the work of such artists as Carpaccio, Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, Venice established a remarkable portraiture tradition.

Anonymous Italian artist

Portrait of a Woman with a Hairnet

Gift of H. P. Kraus, 1961

The artist who drew this sensitive portrait remains unknown. It probably was made during the first quarter of the sixteenth century by an individual from the Veneto or Lombardy working in the circle of Giovanni Bellini, Francesco Bonsignori, or Bartolomeo Veneto.

The sitter's headdress derives from Leonardo's Portrait of a Woman, known as La Belle Ferronière (Louvre, Paris). Painted in the 1490s, that work was much studied during the early years of the sixteenth century.

Portraiture

Inspired by earlier northern European models, Venetian artists of the sixteenth century approached portraiture with a new naturalism. Portraits of individuals were commissioned to document physical likeness as well as social status, often conveyed through opulent clothing and lavish settings. Initially, most sitters were portrayed in strict profile, much like the depictions on ancient coins. Later, evocative three-quarter or frontal views dominated, inviting a more direct and intimate relationship with the viewer. In Venice and northern Italy, group portraits became fashionable. The artist Palma Giovane, for example, produced numerous quick sketches of his large family and wide circle of friends. Through the work of such artists as Carpaccio, Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, Venice established a remarkable portraiture tradition.

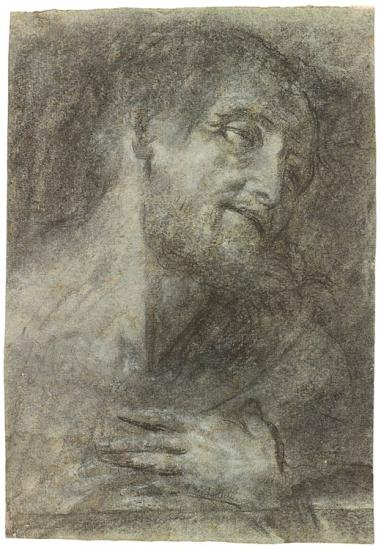

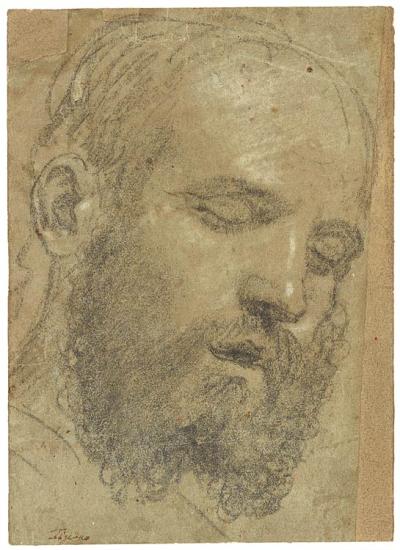

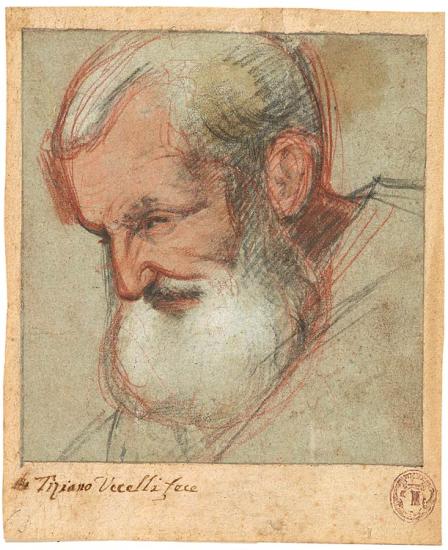

Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo

Head and Shoulders of a Bearded Man

Gift of Benjamin Sonnenberg, 1977

Brescian by birth, Savoldo lived in Venice from at least 1520 until 1548. He was an exceptionally rare draftsman, to whom only about fifteen drawings have been attributed. His drawings exhibit the same sense of atmosphere and luminosity that characterize the chalk drawings of Titian, Lotto, and other painters of the Venetian school.

The sitter is shown in contemporary dress. His sidelong glance leveled at the viewer and full lips—parted as if about to speak—make this one of the most intriguing of Savoldo's portraits.

Portraiture

Inspired by earlier northern European models, Venetian artists of the sixteenth century approached portraiture with a new naturalism. Portraits of individuals were commissioned to document physical likeness as well as social status, often conveyed through opulent clothing and lavish settings. Initially, most sitters were portrayed in strict profile, much like the depictions on ancient coins. Later, evocative three-quarter or frontal views dominated, inviting a more direct and intimate relationship with the viewer. In Venice and northern Italy, group portraits became fashionable. The artist Palma Giovane, for example, produced numerous quick sketches of his large family and wide circle of friends. Through the work of such artists as Carpaccio, Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, Venice established a remarkable portraiture tradition.

Paris Bordone

Head of a Bearded Sleeping Man

Inscribed at lower left, in pen and brown ink, Tiziano.

Gift of Janos Scholz, 1981

In comparison to Bordone's more forcefully drawn Standing Man Playing a Viola da Gamba, here the emphasis is on the shimmering surface of the subject's skin. The artist was strongly influenced by the chalk style of Titian, to whom the present sheet was once ascribed. The candid naturalism of this intimate study of a sleeping man suggests it was done from life.

Of the several paintings and frescoes by Bordone that feature similar sleeping figures, the artist's Last Supper in San Giovanni in Bragora, Venice, in which St. John rests his head on Christ's shoulder, relates most closely to this drawing.

Portraiture

Inspired by earlier northern European models, Venetian artists of the sixteenth century approached portraiture with a new naturalism. Portraits of individuals were commissioned to document physical likeness as well as social status, often conveyed through opulent clothing and lavish settings. Initially, most sitters were portrayed in strict profile, much like the depictions on ancient coins. Later, evocative three-quarter or frontal views dominated, inviting a more direct and intimate relationship with the viewer. In Venice and northern Italy, group portraits became fashionable. The artist Palma Giovane, for example, produced numerous quick sketches of his large family and wide circle of friends. Through the work of such artists as Carpaccio, Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, Venice established a remarkable portraiture tradition.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

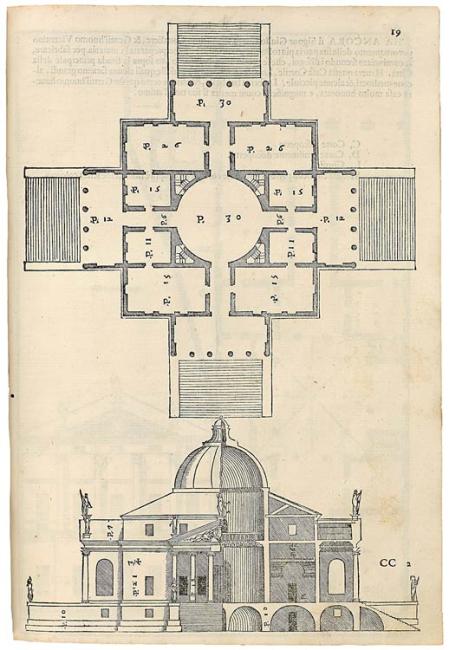

Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio (1508–1580)

I quattro libri dell'architettura (Four Books on Architecture)

Printed by Dominico de' Franceschi in Venice, 1570

Opening: Plan and Elevation of Villa La Rotonda

Gift of Paul Mellon, 1979

PML 76057

The architect Andrea Palladio's literary masterwork, the treatise I quattro libri dell'architettura, begun in 1555, profoundly influenced Western architecture.

This illustration presents a plan and an elevation of Palladio's Villa La Rotonda, just outside Vicenza. The design is for a completely symmetrical building with a square plan around a central circular hall with a dome. Each of the four facades has a portico.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

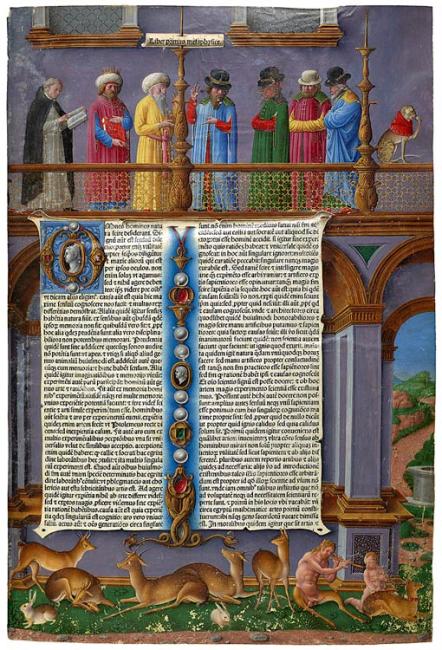

Aristotle

Aristotle

Opera (Works)

Printed on vellum by Andrea Torresanus and Bartolomeo de Blavis in Venice, 1483

Opening, Volume 1: Aristotle and Averroes Disputing by Girolamo da Cremona

Purchased in 1919

PML 21194-95

This luxurious two-volume edition of the works of Aristotle was called by Henry Yates Thompson "the most magnificent book in the world." The trompe-l'oeil tendencies already evident in Girolamo da Cremona's Augustine of 1475 have been developed even further in the two frontispieces of this copy. In the first volume, the vellum of the page appears to have been torn away to reveal Aristotle conversing with a turbaned figure, possibly the Cordovan commentator Averroës (1126–1190). Beneath is a richly decorated architectural façade set into a landscape populated with satyrs, putti, and deer. A Latin inscription on the façade states that one Petrus Ulmer "brought this Aristotle to the world." Some scholars have identified this figure with Peter Ugelheimer, a Frankfurt bookseller resident in Venice who sold to Torresanus the punches of the celebrated printer Nicolas Jenson.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

Aristotle

Aristotle

Opera (Works)

Printed on vellum by Andrea Torresanus and Bartolomeo de Blavis in Venice, 1483

Opening, Volume 2: Group of Philosophers Disputing by Girolamo da Cremona

Purchased in 1919

PML 21194-95

The text of Aristotle's Metaphysics is embellished by a group of disputing philosophers, including at far left a Dominican (probably Thomas Aquinas) and again Averroes (third from left).

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

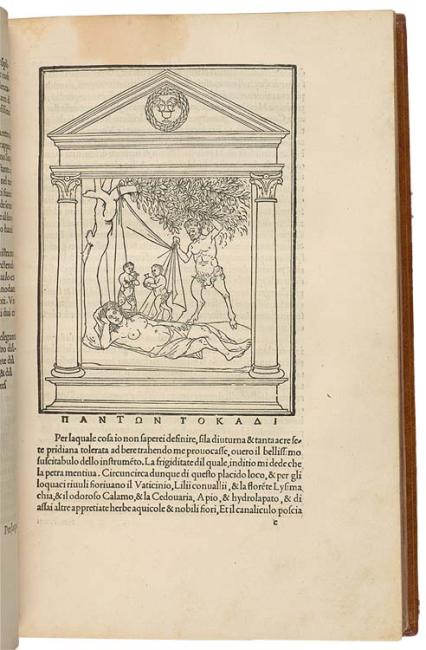

Attributed to Francesco Colonna

Attributed to Francesco Colonna

(1433–1527)

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Poliphilo's Strife of Love in a Dream)

Printed by Aldus Manutius in Venice, 1499

Opening: Nymph Discovered by a Satyr

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan with the library of Theodore Irwin, 1900

PML 373

Because of its elegant page layout, roman typeface, and refined woodcut illustrations, this famous example of early printing has been called the most beautiful illustrated book printed in Italy in the fifteenth century. The woodcuts are thought to have been designed by Benedetto Bordone, a successful miniaturist who turned to new artistic activities in the age of printing.

Written as an allegorical romance, the Hypnerotomachia tells of Poliphilo, who pursues his love, Polia, through a dreamlike landscape. The nymph discovered by a satyr shown here is thought to have inspired Giorgione's painting of around 1510, Venus Reclining (Dresden), considered the first painting of a female nude since antiquity.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

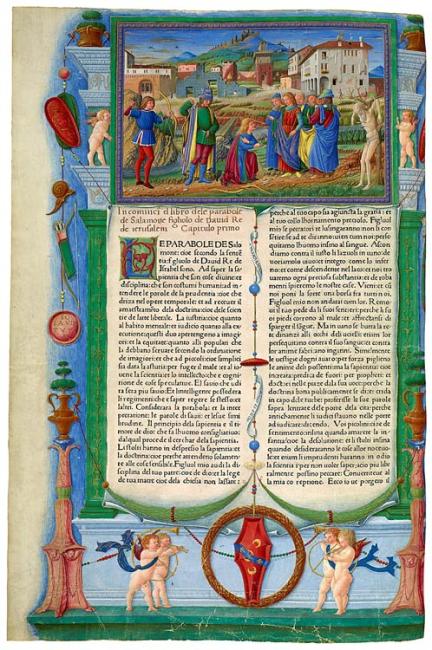

Biblia

Biblia

Translated into Italian by Niccolò Malermi.

Opening, Volume 2: Shooting of the Father's Corpse

Printed on vellum by Vindelinus de Spira in Venice 1 August 1471

Purchased in 1929 PML 26984

This is the frontispiece to the second volume of the 1471 bible. The text appears to have been printed on a frayed piece of parchment suspended from an architectural monument—one of the most ambitious pictorial illusions in a Venetian book created during the Renaissance.

The framed picture at top illustrates the Shooting of the Father's Corpse, one of the apocryphal judgments of Solomon. In an inheritance dispute between the true son of a recently deceased man and an impostor, the actual son kneels before the suspended corpse, while the impostor reveals his counterfeit status by following King Solomon's command to shoot at the corpse.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

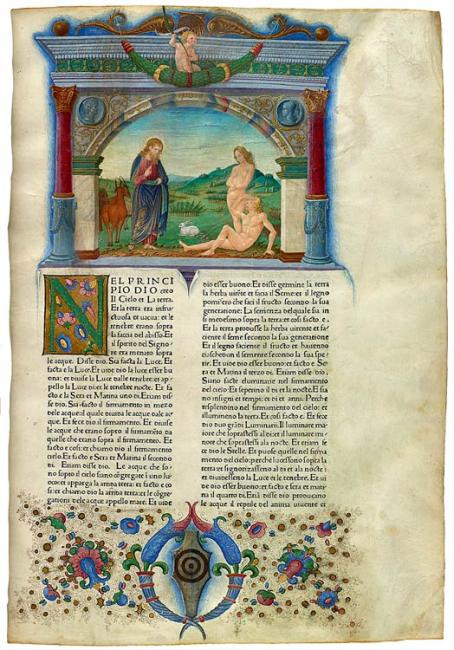

Biblia

Biblia

Printed on vellum by Vindelinus de Spira in Venice, 1 August 1471

Translated into Italian by Niccolò Malermi.

Opening, Volume 1: Creation of Eve

Purchased in 1929 PML 26983

Item description:

Professional illuminators supplied borders and initials for some of the first books printed in Venice, a center of the book trade with an affluent clientele prepared to pay handsomely for special copies decorated no less lavishly than the illuminated manuscripts of the day. An anonymous miniaturist known as the Master of the Putti produced this stunning trompe l'oeil frontispiece for the second volume of the Malermi Bible, the first edition of the Bible translated into Italian. In the framed miniature, Solomon reveals the rightful heir to an estate by having him and his heartless brothers shoot at their father's corpse, a task beyond the powers of a truly devoted son.

Most bibles were written or published in Latin. This copy, printed by Vindelinus de Spira, is in Italian. It is one of the earliest bibles published in the vernacular.

Gold highlights in The Creation of Eve, shown at the top of the page, create the impression of a sun-drenched landscape. Although the miniatures in both volumes of this bible may be attributed to the Master of the Putti, the two books originally may not have belonged together. This one may have belonged to the Cornaro family of Venice (their shield is covered by a later coat of arms), whereas the second volume displays the arms of the Macigni family.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

Cesare Vecellio

Cesare Vecellio

(1521–1601)

Degli habiti, antichi et moderni di diversi parti del mondo (Of Costumes, Ancient and Modern, of Different Parts of the World)

Printed by Damian Zenaro in Venice, 1590

Opening: Woman Blonding Her Hair

Purchased with the Toovey Collection, 1899

PML 9626

Vecellio initially joined the workshop of his famous cousin Titian, but by 1570 was primarily active as a publisher. This book contains woodcut illustrations of costumes—exotic and domestic—and marks the culmination of a trend that began with the increase in travel during the mid-sixteenth century. Highly popular, this most famous example of costume books became a model of the genre.

The woman shown here is assiduously trying to make her hair a lighter shade of blonde with the help of different liquids. Her pianelle, high platform shoes, stand nearby.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

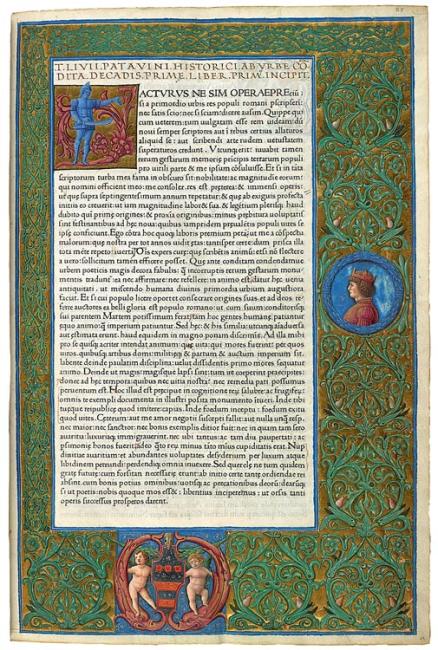

Livy (Titus Livius Patavinus)

Livy (Titus Livius Patavinus)

Historiae romanae decades (Roman History)

Opening: Illuminated Page with the Coat of Arms of the Venetian Donà Family

1470

Printed on vellum by Vindelinus de Spira in Venice

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan with the library of Theodore Irwin, 1900

PML 266

Livy's Historiae romanae decades was one of the first classical Latin texts to be printed in Venice. The book and chapter headings, at the top in gold, were added by a trained scribe. Woodcut patterns that served to guide the miniaturist were stamped into the margins after printing and appear underneath the intense green vine motifs contrasting with gold ground of the painted borders. The blue soldier in Roman armor with an outstretched arm represents the letter F, thus providing the initial for the first word on the page, Facturus.

Printing

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility.

The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

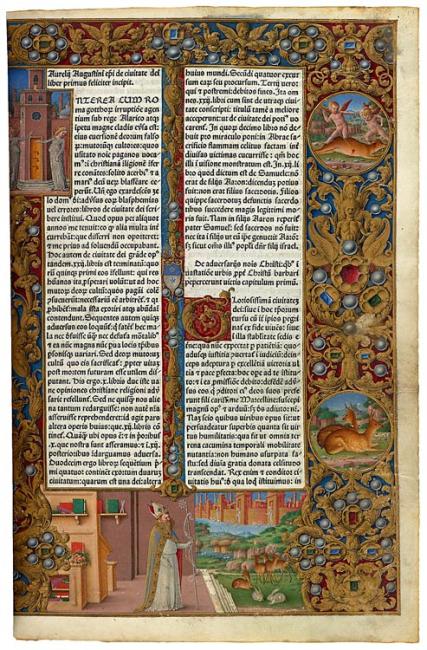

St. Augustine

St. Augustine

De civitate dei

Venice: Nicolas Jenson, 2 October 1475

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan with the library of Theodore Irwin, 1900

PML 310

Many magnificent books were printed in Venice. This copy of De civitate Dei left the printing press without initials and decorative borders, which were added by hand—probably by Girolamo da Cremona. The lavish frontispiece depicts St. Augustine standing to the side of his scholarly study before a distant landscape. The Heavenly City of his vision, with angelic guardians standing at the gates, floats in the distance. Clearly a luxury item, this book was printed on vellum. Set unobtrusively, near the center of the page, is the blue-and-white coat of arms of the Mocenigo family. Pietro Mocenigo was doge of Venice from 1474 to 1476; the volume probably once belonged to him.

In 1469—some fourteen years after Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible using movable type—this transformative technology arrived in Venice, and the city rapidly became Europe's preeminent center for book publishing. During the last few decades of the fifteenth century, a new kind of volume appeared: the hand-illuminated printed book. Trained scribes and artists carefully added chapter headings, initials, borders, and lavish frontispieces to the printed text. These luxury items were created for a wealthy and prominent clientele—predominantly Venetian nobility. The impossibility of hand decorating ever-increasing numbers of books led Venetian printers to adopt mechanical means to embellish their printed texts. From the 1490s, it became common to illustrate books by incorporating woodcuts. As the market for printed material flourished, artists such as Titian and Battista Franco produced masterly woodcuts and engravings to enhance their reputations.

Innovations in Drawing

Technical and artistic innovations combined to make Renaissance Venice a vital creative center. Late-fifteenth-century artists generally worked in pen and ink and wash to make relatively finished drawings, but new techniques emerged that enabled them to produce more diverse, and often dramatic, effects. Artists such as Vittore Carpaccio perfected a method of applying ink with a brush onto Venetian blue paper (carta azzurra)—a support greatly prized by Albrecht Dürer. Artists of Titian and Bordone's generation, followed by Tintoretto, preferred a soft black chalk that was ideally suited to record tonal subtleties and create impressions of movement. Jacopo Bassano's innovative use of colored chalks made him a precursor to the pastel tradition. Tintoretto's younger contemporary, Veronese, developed entire compositions with rapid pen sketches while retaining a typically Venetian preoccupation with light.

Jacopo Tintoretto

Roman Head (So-Called Head of Emperor Vitellius)

Purchased as the gift of Mr. and Mrs. Carl Stern, 1959

This drawing depicts a Roman portrait bust sent to Venice by Cardinal Domenico Grimani and exhibited in the Ducal Palace from 1525 to 1593. Traditionally it was thought to represent the Roman emperor Vitellius, famous for his indolence and gluttony. A plaster cast of this antique sculpture was documented in Tintoretto's studio.

About twenty studies of this bust by Tintoretto and his pupils are known. The present version portrays the head from a low vantage point, emphasizing the massive neck and jowls, with vigorous parallel hatching and sharp highlights making the figure look particularly alive and dramatic.

Innovations in Drawing

Technical and artistic innovations combined to make Renaissance Venice a vital creative center. Late-fifteenth-century artists generally worked in pen and ink and wash to make relatively finished drawings, but new techniques emerged that enabled them to produce more diverse, and often dramatic, effects. Artists such as Vittore Carpaccio perfected a method of applying ink with a brush onto Venetian blue paper (carta azzurra)—a support greatly prized by Albrecht Dürer. Artists of Titian and Bordone's generation, followed by Tintoretto, preferred a soft black chalk that was ideally suited to record tonal subtleties and create impressions of movement. Jacopo Bassano's innovative use of colored chalks made him a precursor to the pastel tradition. Tintoretto's younger contemporary, Veronese, developed entire compositions with rapid pen sketches while retaining a typically Venetian preoccupation with light.

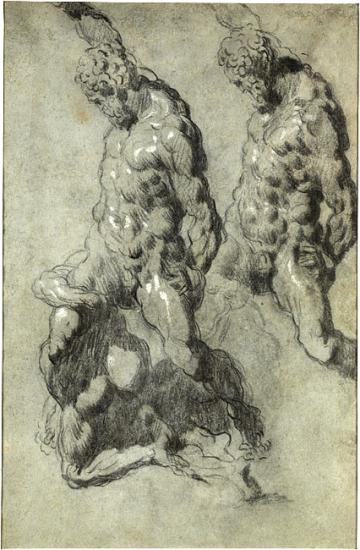

Jacopo Tintoretto

Two Studies of Samson Slaying the Philistines (Judges 15:14–19)

Thaw Collection, 2005

The present sheet is among the more than thirty studies Tintoretto and his workshop produced after a wax or clay replica of Michelangelo's 1528 sculptural model for Samson Slaying the Philistines. The spiraling and radically foreshortened figure of Samson wielding the jawbone of an ass atop one of his victims must have held a particular fascination for the artist, who rose to the challenge of producing a two-dimensional image of the sculpture with admirable skill.

In 1528 the republic of Florence commissioned Michelangelo to create a marble group representing Samson slaying the Philistines. The artist prepared a model but never executed the sculpture. Tintoretto owned a wax or clay model after Michelangelo's design, which is recorded in several drawings by him and members of his workshop. Tintoretto is said to have produced drawings after sculpture and "all good things" throughout his career, including statues by Jacopo Sansovino and casts of sculptures by Michelangelo and Giovanni Bologna.

Tintoretto's characteristic swelling contours and sharp flicks of the chalk heighten the drawing's sense of drama.

Innovations in Drawing

Technical and artistic innovations combined to make Renaissance Venice a vital creative center. Late-fifteenth-century artists generally worked in pen and ink and wash to make relatively finished drawings, but new techniques emerged that enabled them to produce more diverse, and often dramatic, effects. Artists such as Vittore Carpaccio perfected a method of applying ink with a brush onto Venetian blue paper (carta azzurra)—a support greatly prized by Albrecht Dürer. Artists of Titian and Bordone's generation, followed by Tintoretto, preferred a soft black chalk that was ideally suited to record tonal subtleties and create impressions of movement. Jacopo Bassano's innovative use of colored chalks made him a precursor to the pastel tradition. Tintoretto's younger contemporary, Veronese, developed entire compositions with rapid pen sketches while retaining a typically Venetian preoccupation with light.

Jacopo Bassano

Head of an Old Man Turned to the Left

Gift of Lore Heinemann in memory of her husband, Dr. Rudolf J. Heinemann, 1998

Although Jacopo and his sons were based in his native Bassano del Grappa in the Veneto, the artist attracted numerous patrons from Venice for his vivid biblical scenes in rural settings.

This drawing is a study for the head of St. Joseph in Jacopo's painting The Flight into Egypt, now in the Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. The painting is dated to the early 1540s on stylistic grounds. The drawing is one of the earliest examples of the artist's highly personal use of black, red, and white chalk on blue paper that was to become the hallmark of his style.

Innovations in Drawing

Technical and artistic innovations combined to make Renaissance Venice a vital creative center. Late-fifteenth-century artists generally worked in pen and ink and wash to make relatively finished drawings, but new techniques emerged that enabled them to produce more diverse, and often dramatic, effects. Artists such as Vittore Carpaccio perfected a method of applying ink with a brush onto Venetian blue paper (carta azzurra)—a support greatly prized by Albrecht Dürer. Artists of Titian and Bordone's generation, followed by Tintoretto, preferred a soft black chalk that was ideally suited to record tonal subtleties and create impressions of movement. Jacopo Bassano's innovative use of colored chalks made him a precursor to the pastel tradition. Tintoretto's younger contemporary, Veronese, developed entire compositions with rapid pen sketches while retaining a typically Venetian preoccupation with light.

Paolo Veronese

Studies for The Finding of Moses, ca. 1580

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

In this lively sheet of studies for the Finding of Moses, circa 1580 (Prado, Madrid), the artist worked in rapid strokes of pen and brown ink to resolve problems not only of pose but of light and volume. The subject derives from the Old Testament account in which Moses was hidden by his mother in the bulrushes to escape Pharoah's order that all male Israelite infants be killed; he was later found and cared for by Pharoah's daughter.

Unlike Titian and Tintoretto—the other members of the triumvirate of extraordinary artists active in Venice during the second half of the sixteenth century—Veronese most commonly drew rough sketches with a fine pen, thin wash, and a light touch, combining several ideas for groups of figures on a single sheet.

The present drawing documents the artist's various ideas for his composition of the Finding of Moses, which he painted in several versions, all thought to date from the 1580s.

Innovations in Drawing

Technical and artistic innovations combined to make Renaissance Venice a vital creative center. Late-fifteenth-century artists generally worked in pen and ink and wash to make relatively finished drawings, but new techniques emerged that enabled them to produce more diverse, and often dramatic, effects. Artists such as Vittore Carpaccio perfected a method of applying ink with a brush onto Venetian blue paper (carta azzurra)—a support greatly prized by Albrecht Dürer. Artists of Titian and Bordone's generation, followed by Tintoretto, preferred a soft black chalk that was ideally suited to record tonal subtleties and create impressions of movement. Jacopo Bassano's innovative use of colored chalks made him a precursor to the pastel tradition. Tintoretto's younger contemporary, Veronese, developed entire compositions with rapid pen sketches while retaining a typically Venetian preoccupation with light.

Terraferma

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Venice's mainland possessions, called the terraferma, stretched westward from Udine nearly all the way to Milan and included Padua, Vicenza, Verona, Brescia, and Bergamo. These Venetian strongholds ensured a continuous food supply and safeguarded trading routes to the north. Even though Venice's enemies combined to form the League of Cambrai and defeated the city in 1509, much of the mainland territory was recovered within a decade.

Venice's political independence and unified territories allowed artists considerable mobility. Some preferred to return to their native cities in Lombardy, Friuli, or the Veneto, where they established flourishing workshops. Distinctive local traditions—such as the realism of the Lombard painters of Bergamo and Brescia—also endured. The Veneto area in particular served as a country retreat for Venice's patrician families, who erected idyllic villas in the classical tradition designed by Andrea Palladio.

Giovanni Antonio da Pordenone

Crucifixion

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Pordenone used this quick exploratory sketch to map out the initial design for his fresco of the Crucifixion painted in 1520–21 on the inner wall of the facade of Cremona cathedral. In order to incorporate changes to the composition, the sheet was cut at the right, where the artist inserted the rectangular piece with the horseman.

The Cremona frescoes are remarkable for their violent expressivity, which borrowed elements from northern painting and prints.

Terraferma

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Venice's mainland possessions, called the terraferma, stretched westward from Udine nearly all the way to Milan and included Padua, Vicenza, Verona, Brescia, and Bergamo. These Venetian strongholds ensured a continuous food supply and safeguarded trading routes to the north. Even though Venice's enemies combined to form the League of Cambrai and defeated the city in 1509, much of the mainland territory was recovered within a decade.

Venice's political independence and unified territories allowed artists considerable mobility. Some preferred to return to their native cities in Lombardy, Friuli, or the Veneto, where they established flourishing workshops. Distinctive local traditions—such as the realism of the Lombard painters of Bergamo and Brescia—also endured. The Veneto area in particular served as a country retreat for Venice's patrician families, who erected idyllic villas in the classical tradition designed by Andrea Palladio.

Battista Franco

Ceiling Design with the Story of the Slave Girls of Smyrna

Inscribed above or below each scene, in pen and brown ink, with descriptions of the episodes depicted

Purchased as a gift of the Fellows, 1984

Seven episodes recount the victory, through female initiative, of the ancient city of Smyrna over the inhabitants of Sardis. When the Sardians offered to end their siege in return for the wives of Smyrna (1), a beautiful slave girl proposed that she and her companions go instead (2). The girls dressed the part and were welcomed by the Sardians (3, 4), who were later taken prisoner when they were overcome by sleep (5) and held captive in Smyrna (6). From then on a festival to Venus was held every year in honor of the slave girls and their victory (7).

The drawing may have served as the design for the decoration of a villa.

Terraferma

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Venice's mainland possessions, called the terraferma, stretched westward from Udine nearly all the way to Milan and included Padua, Vicenza, Verona, Brescia, and Bergamo. These Venetian strongholds ensured a continuous food supply and safeguarded trading routes to the north. Even though Venice's enemies combined to form the League of Cambrai and defeated the city in 1509, much of the mainland territory was recovered within a decade.

Venice's political independence and unified territories allowed artists considerable mobility. Some preferred to return to their native cities in Lombardy, Friuli, or the Veneto, where they established flourishing workshops. Distinctive local traditions—such as the realism of the Lombard painters of Bergamo and Brescia—also endured. The Veneto area in particular served as a country retreat for Venice's patrician families, who erected idyllic villas in the classical tradition designed by Andrea Palladio.

Paolo Veronese

Studies of Jupiter Astride the Eagle

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Like the studies of Bacchus and Apollo in the Morgan's collection, the present drawing is associated with Veronese's frescoes on the vault of the upper loggia in the Palazzo Trevisan, Murano.

Veronese likely kept the present sheet in his workshop, for the upper sketch of Jupiter astride his eagle was reused in a now lost ceiling canvas executed for the Palazzo Pisani, Venice.

Terraferma

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Venice's mainland possessions, called the terraferma, stretched westward from Udine nearly all the way to Milan and included Padua, Vicenza, Verona, Brescia, and Bergamo. These Venetian strongholds ensured a continuous food supply and safeguarded trading routes to the north. Even though Venice's enemies combined to form the League of Cambrai and defeated the city in 1509, much of the mainland territory was recovered within a decade.

Venice's political independence and unified territories allowed artists considerable mobility. Some preferred to return to their native cities in Lombardy, Friuli, or the Veneto, where they established flourishing workshops. Distinctive local traditions—such as the realism of the Lombard painters of Bergamo and Brescia—also endured. The Veneto area in particular served as a country retreat for Venice's patrician families, who erected idyllic villas in the classical tradition designed by Andrea Palladio.

Lattanzio Gambara

Massacre of the Innocents

Gift of Janos Scholz, 1980

With the death of his teacher and father-in-law, Girolamo Romanino, in 1560, Gambara became the leading artist in Brescia. Completed in 1573, the frescoes in the nave arcade and internal facade of Parma cathedral depicting scenes from the life of Christ were his most prestigious commission. This is a late compositional study for one of those scenes, Massacre of the Innocents, which includes The Flight into Egypt as a vignette at upper left. The daringly foreshortened horse and rider at right reveal the influence of Pordenone.

Terraferma

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Venice's mainland possessions, called the terraferma, stretched westward from Udine nearly all the way to Milan and included Padua, Vicenza, Verona, Brescia, and Bergamo. These Venetian strongholds ensured a continuous food supply and safeguarded trading routes to the north. Even though Venice's enemies combined to form the League of Cambrai and defeated the city in 1509, much of the mainland territory was recovered within a decade.

Venice's political independence and unified territories allowed artists considerable mobility. Some preferred to return to their native cities in Lombardy, Friuli, or the Veneto, where they established flourishing workshops. Distinctive local traditions—such as the realism of the Lombard painters of Bergamo and Brescia—also endured. The Veneto area in particular served as a country retreat for Venice's patrician families, who erected idyllic villas in the classical tradition designed by Andrea Palladio.

Travel and the Venetian Empire

By 1500 Venice was the foremost maritime power in Europe as well as an international cultural destination. The city's empire included a dense web of fortified harbors in the eastern Mediterranean stretching along the Dalmatian coast to Crete and Cyprus, which protected its trading interests. In order to cater to the needs of its merchants and naval commanders, Venice became an important center of cartography.

The city's wealth and stability fostered artistic creativity and attracted a host of influential foreign artists, such as Albrecht Dürer, Andrea Schiavone, and El Greco. Not only did these visiting artists invigorate the city's artistic life, they also spread Venetian innovations far beyond the territorial confines of the empire.

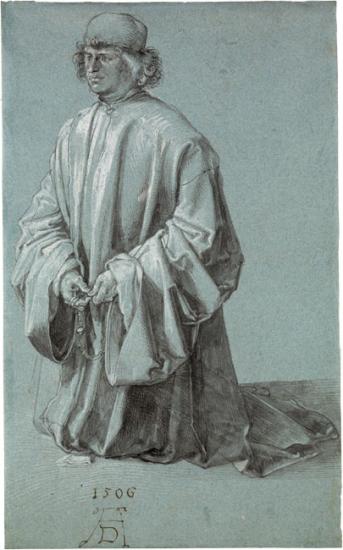

Albrecht Dürer

Kneeling Donor, 1506

Signed with the artist's monogram and dated, at lower left, in brown ink, 1506.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Dürer's interest in proportion and portraiture unite in this religious subject. This study is for one of his most prestigious commissions, the Feast of the Rose Garlands, an altarpiece now in the National Gallery, Prague. Created for the German Confraternity of the Rosary in Venice, it originally stood in the church of San Bartolomeo. While this figure corresponds to one of the donors flanking the Virgin and Child in the painting, the drawing is not merely a preparatory sketch but a highly finished work of art. Dürer chose a rich blue paper—the Venetian carta azzurra that he adopted during his 1505–7 sojourn in Italy—and used black and white heightening to achieve a full range of tonal effects.

During his sojourn in Venice from 1505 to 1507, Dürer received the important commission to paint The Feast of the Rose Garlands for the German Confraternity of the Rosary. It was to hang in their national church, San Bartolomeo, prominently located near the Rialto.

The drawing is a study for one of the principal donors in the painting—possibly a member of the Fugger family—seen holding a rosary and kneeling in the right foreground. It is drawn with the point of the brush on blue paper, a technique that had become customary among Venetian painters during the late fifteenth century.

Travel and the Venetian Empire

By 1500 Venice was the foremost maritime power in Europe as well as an international cultural destination. The city's empire included a dense web of fortified harbors in the eastern Mediterranean stretching along the Dalmatian coast to Crete and Cyprus, which protected its trading interests. In order to cater to the needs of its merchants and naval commanders, Venice became an important center of cartography.

The city's wealth and stability fostered artistic creativity and attracted a host of influential foreign artists, such as Albrecht Dürer, Andrea Schiavone, and El Greco. Not only did these visiting artists invigorate the city's artistic life, they also spread Venetian innovations far beyond the territorial confines of the empire.

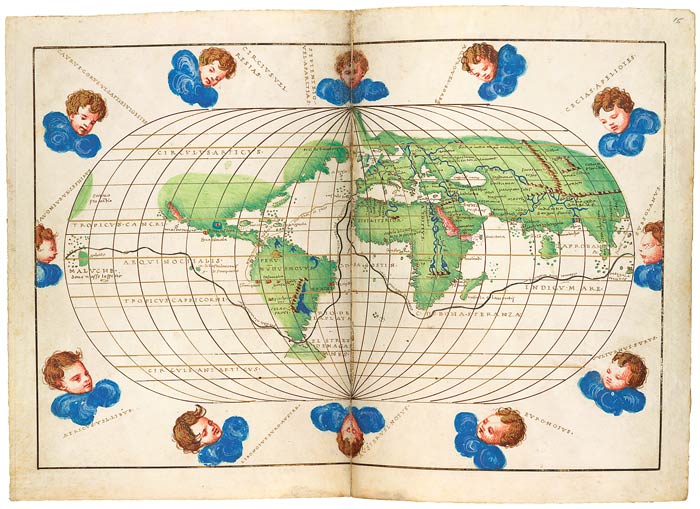

Battista Agnese

Battista Agnese

(ca. 1500–1564)

Portolan Atlas, on vellum

Opening: Map of the World with Magellan's Route 1536–64

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1912

MS M.507

Between 1536 and 1564, the heyday of Italian mapmaking, the cartographer Battista Agnese produced in Venice a number of remarkably accurate and beautifully decorated nautical or "portolan" atlases. About seventy copies are known to exist today. A luxury item, the atlas was unlikely to have been used in practical navigation and was reserved for rich merchants and high-ranking officials.

The map with twelve wind cherubs traces Ferdinand Magellan's sea route for his near circumnavigation of the world (he died before completing it) in 1519–22 along with a route from Spain to Peru. The oval depiction of the world represented a new type of map introduced by Benedetto Bordone's Isolario (Book of Islands).

Travel and the Venetian Empire

By 1500 Venice was the foremost maritime power in Europe as well as an international cultural destination. The city's empire included a dense web of fortified harbors in the eastern Mediterranean stretching along the Dalmatian coast to Crete and Cyprus, which protected its trading interests. In order to cater to the needs of its merchants and naval commanders, Venice became an important center of cartography.

The city's wealth and stability fostered artistic creativity and attracted a host of influential foreign artists, such as Albrecht Dürer, Andrea Schiavone, and El Greco. Not only did these visiting artists invigorate the city's artistic life, they also spread Venetian innovations far beyond the territorial confines of the empire.

Benedetto Bordone

Benedetto Bordone

(1460–1531)

Isolario (Book of Islands)

Printed by Nicolò Zappino in Venice, 1528

Opening: Map of Vinegia (Venice)

Gift of Lydia L. Redmond, in memory of her mother and stepfather, Mr. and Mrs. William M. Clearwater, 1996

PML 125859

Originally intended as a guide for sailors, Bordone's Isolario describes the important islands and ports throughout the Mediterranean and in other parts of the world, also touching on their culture and history. Some of the illustrations are among the earliest printed maps of the regions depicted. The book also includes new discoveries, such as the connection between North and South America. The polymath Bordone—a miniaturist, astrologer, engraver, and cartographer—helped to establish island books as a popular new genre in Italy, and many were produced in Venice.

This marvelously detailed map of Venice (Vinegia) provides an excellent perspective of the lagoon and surrounding islands, detailing the major canals and landmarks in and around the city.

Travel and the Venetian Empire

By 1500 Venice was the foremost maritime power in Europe as well as an international cultural destination. The city's empire included a dense web of fortified harbors in the eastern Mediterranean stretching along the Dalmatian coast to Crete and Cyprus, which protected its trading interests. In order to cater to the needs of its merchants and naval commanders, Venice became an important center of cartography.

The city's wealth and stability fostered artistic creativity and attracted a host of influential foreign artists, such as Albrecht Dürer, Andrea Schiavone, and El Greco. Not only did these visiting artists invigorate the city's artistic life, they also spread Venetian innovations far beyond the territorial confines of the empire.