Peacocks of the Midcentury

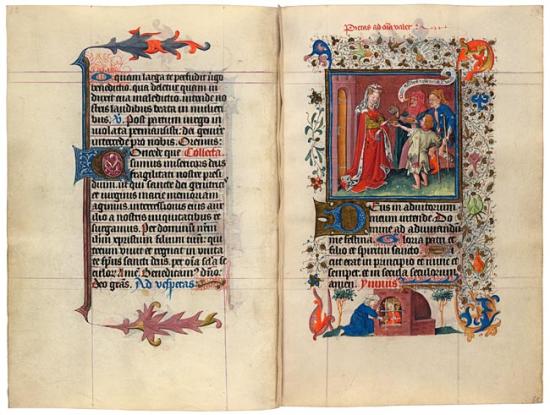

Hours of Catherine of Cleves, in Latin

Illuminated by the eponymous Master of Catherine of Cleves

Purchased on the Belle da Costa Greene Fund and with the assistance of the Fellows

Catherine of Cleves Shows Off

Although duchess of Guelders, in the northern Netherlands, Catherine was also the niece of Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy. For reasons of culture — and snobbery — she leaned toward the duchy of her famous uncle with its opulent court and extravagant clothes. In this portrait, Catherine, while humbly distributing alms, could not be more richly attired. Her voluminous ermine-lined houpeland, with cascading bombard sleeves, harks back to the luxurious early decades of the century. Her hair is enmeshed in reticulated gold temples. The boy receiving her coin is dressed in a hand-me- down, a handsomely tailored gown once owned by a wealthy man.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

St. Adrian as a Fashion Plate (Part 2)

Book of Hours, in Latin and French

Illuminated by a Master of the Gold Scrolls

Gift of Julia Parker Wightman, 1993

That artists kept the clothing they depicted in their illuminations current is confirmed by comparing this Adrian with the one exhibited in Section 3. Here the saint is also well-attired, albeit in styles from around 1440. He wears a fur-lined, knee-length gown that is belted at the waist. The regular pleating and the slightly opened V neck, above which juts the collar of his doublet, are new features of the tailoring. Also new is his fur hat with its round crown and wide brim. Adrian's attributes include the anvil and hammer that were used to break his bones.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

Women's Headgear Achieves New Heights

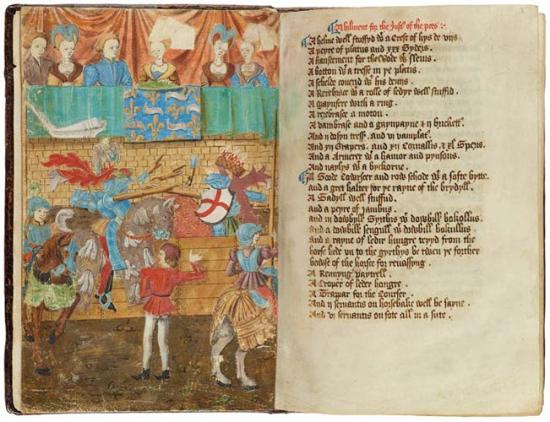

Ordinances of Chivalry, in English and Latin

Purchased, 1931

These men and women seated in a viewing stand watch a joust (in which lances are violently breaking). The two men wear the short gown — as does the squire in red in the foreground — with narrow pleats and raised shoulders. The muscular look is achieved by mahewters, padded rolls that enlarge the upper arms. Women wear fashionable gowns with wide V necks and partlets covering the bosom. (In addition, two of the women cover their fronts with fine linen.) Atop their temples two women wear thick V-shaped burlets, while the other two have butterfly veils that, supported by wires, sail high above their heads.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

Musicians Have Always Been Snappy Dressers

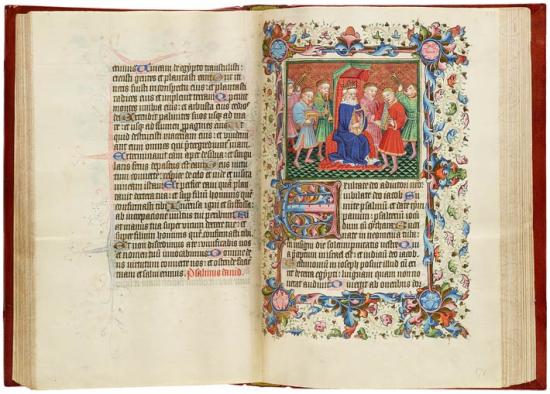

Warwick Psalter-Hours, in Latin

Purchased on the Belle da Costa Greene Fund, with the assistance of the Fellows, and the special assistance of the Hon. Robert Woods Bliss, Mrs. W. Murray Crane, Mr. Childs Frick, Mr. William S. Glazier, Mrs. Matilda Geddings Gray, Mr. Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. Donald F. Hyde, Mr. Milton McGreevy, Colonel David McC. McKell, Mr. Joseph V. Reed, Mrs. Landon K. Thorne, Mr. Ralph Walker, Mr. Christian A. Zabriskie, and an anonymous foundation, 1958

Psalm 80 in medieval Psalters was traditionally illustrated with an image of David playing the harp. In this prayer book, a group of young men — all fashionably attired — joins the king in making music with a variety of instruments. They wear the knee-length, fur-lined gown, belted at the waist and with a full or slit skirt. Pleats at the skirt, bodice, and upper sleeves make the garment quite ample. The man's gown evolves quickly: the skirt gets shorter and the shoulders get wider. The musicians sport the bowl haircut called a "not heed."

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

St. Julian Accidentally Kills His Parents

Golden Legend, in French

Illuminated by the Sapience Master

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Julian slew his wife and her lover in bed, only to discover later that the people he killed were actually his parents. The saint is dressed in a man's elegant gown. Below a cinched waist, the gown flares into a skirt so short it barely covers his buttocks. Above the waist the gown expands, accentuating the torso. Tight pleats, gathered at the front and back, flatter the swelling forms of chest, back, and buttocks. Together, the pleats and padded shoulders create the flattering V shape of the masculine silhouette. Tall boots and slit sleeves accent the lean look.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

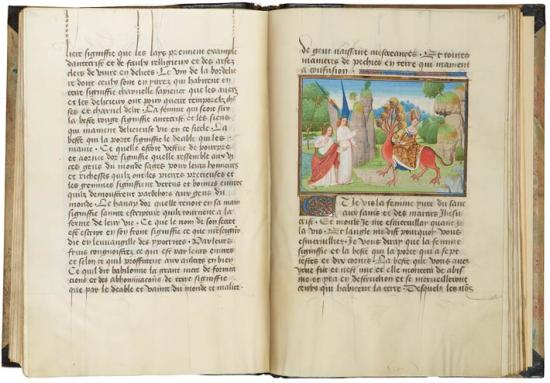

The Whore of Babylon Dresses the Part

Epistolary and Apocalypse of Charles the Bold, in French

Illuminated by Loyset Liédet and his workshop

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1905

Dressed extravagantly in scarlet cloth of gold, the Whore of Babylon rides the seven-headed beast. Although this manuscript was created around 1470, the Whore's headgear dates to the 1450s. Atop toweringly tall reticulated temples rests the thick rolls of a V-shaped burlet, behind which fall the dags of what was originally the burlet's cape. This headgear can go no further: it is as tall — and its burlet as close together — as can be. By 1470 it was seen as not just old-fashioned, but also decadent. (The styling of the Whore's gown, however, is characteristic of the period around 1470.)

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

St. Eugenia's Clothes Are Encoded

Golden Legend, in French

Illuminated by the Master of the Jardin de vertueuse consolation

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

SS. Protus and Hyacintus wear the full-length version of the man's gown — an alternate garment often preferred by middle-aged or older men. Above a full skirt, the torso was the same as with the short gown: pleats and padded shoulders formed a flattering male silhouette. Eugenia's attire, however, is anachronistic: the low wide neck and tippets hanging from her sleeves hark back to the fourteenth century. Her bejeweled turban (like that worn by the Roman emperor at the right) is complete fantasy. The illuminator used out-of-date and invented garments to place the martyrdom in a distant time and place, third-century Rome.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.