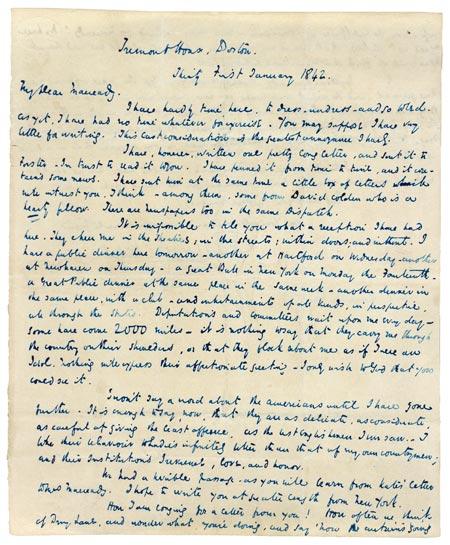

A Letter from Charles Dickens

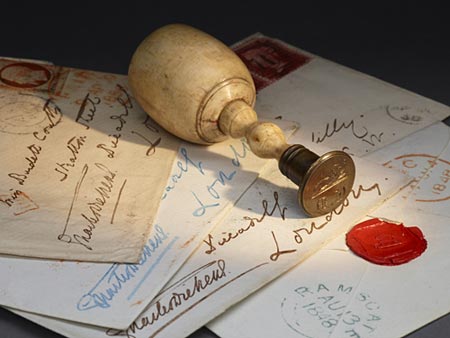

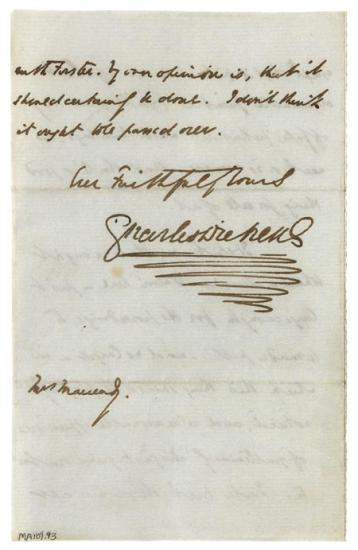

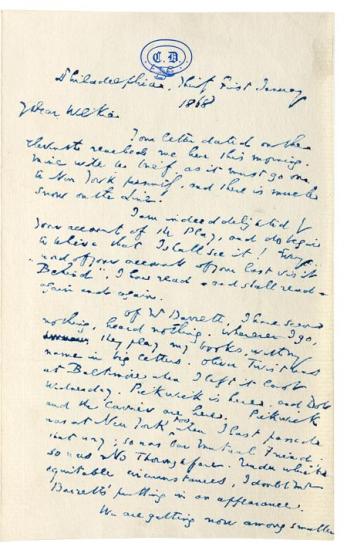

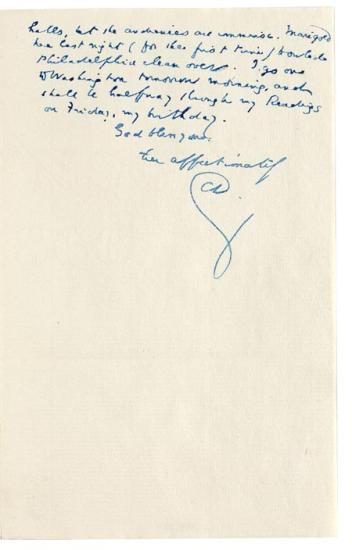

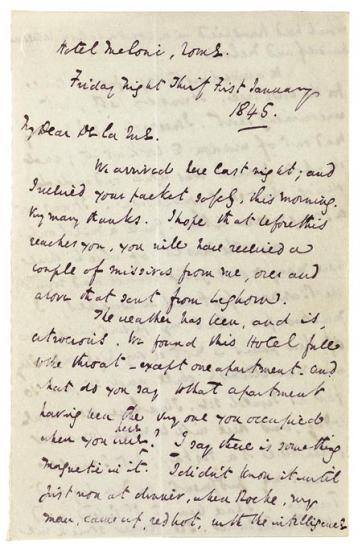

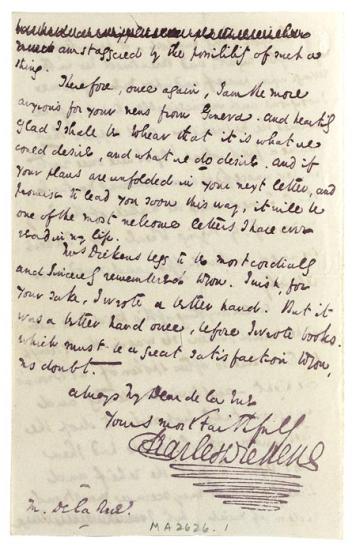

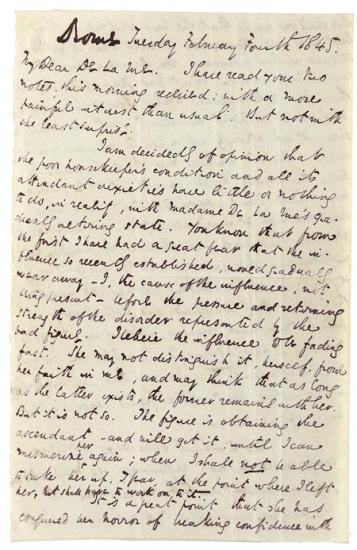

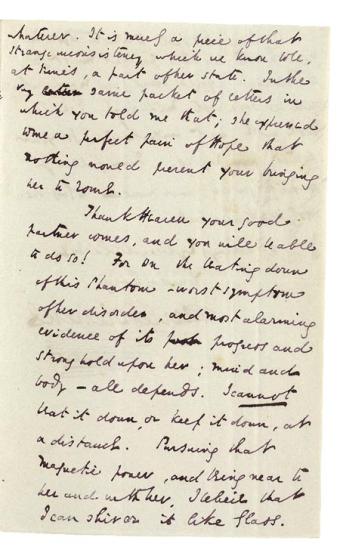

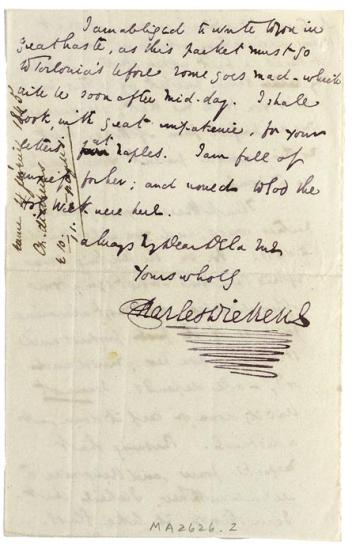

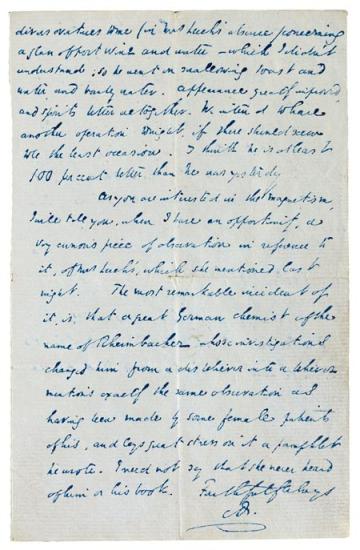

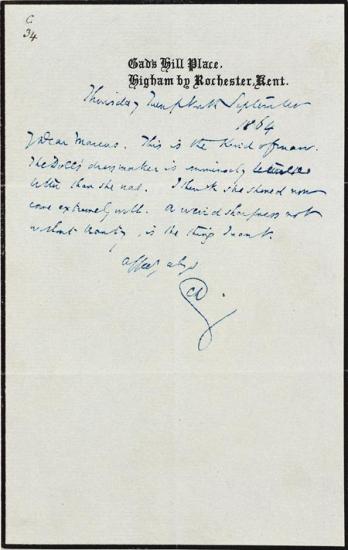

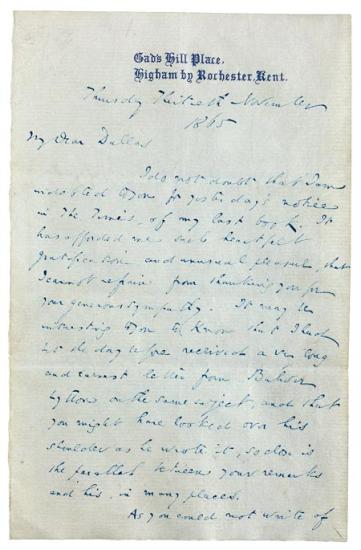

The letters of Charles Dickens (1812–1870) are exceptionally brilliant and entertaining and, alongside his literary manuscripts, provide great insight into his craftsmanship and imagination. Using a goose quill pen, he generally wrote from nine o'clock each morning until two in the afternoon. He favored black ink, now faded to brown, but in the late 1840s switched to blue paper and blue ink. Though Dickens would have preferred that his correspondence remain private, many recipients treasured and retained the letters he sent them, and some 15,000 have survived. The twenty featured here, selected from the Morgan's collection of over 1500 (the richest in the United States), track not only his work as a novelist but also his visits to the United States, his philanthropic pursuits, and his lesser-known experiments with an early form of hypnotism.

The letters of Charles Dickens (1812–1870) are exceptionally brilliant and entertaining and, alongside his literary manuscripts, provide great insight into his craftsmanship and imagination. Using a goose quill pen, he generally wrote from nine o'clock each morning until two in the afternoon. He favored black ink, now faded to brown, but in the late 1840s switched to blue paper and blue ink. Though Dickens would have preferred that his correspondence remain private, many recipients treasured and retained the letters he sent them, and some 15,000 have survived. The twenty featured here, selected from the Morgan's collection of over 1500 (the richest in the United States), track not only his work as a novelist but also his visits to the United States, his philanthropic pursuits, and his lesser-known experiments with an early form of hypnotism.

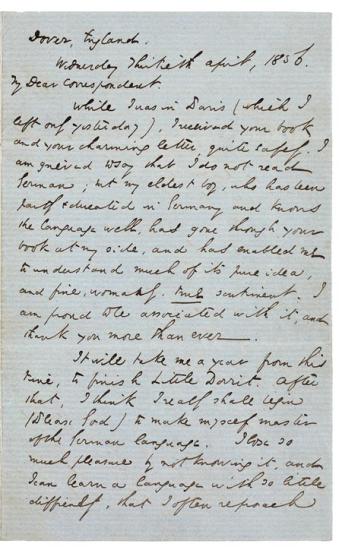

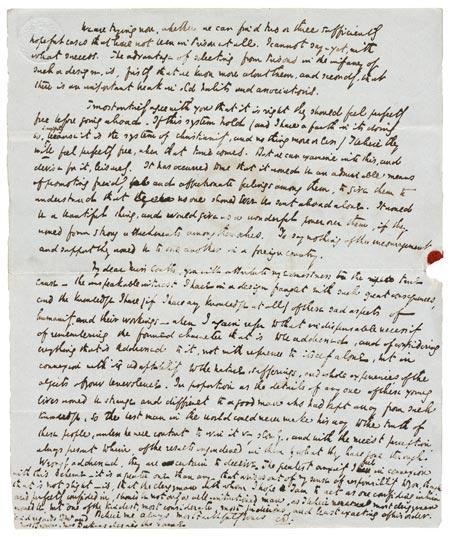

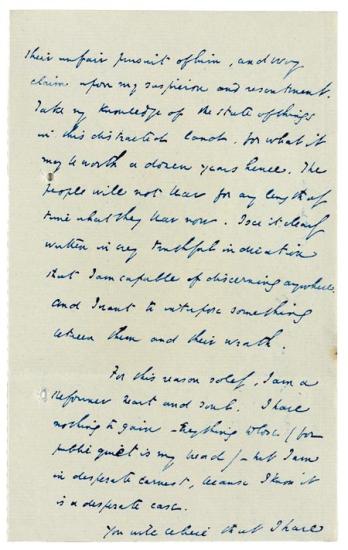

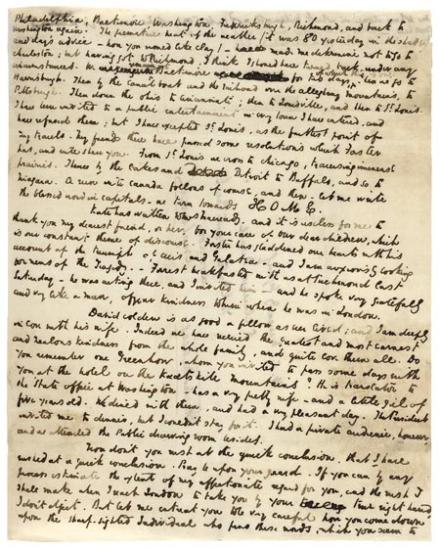

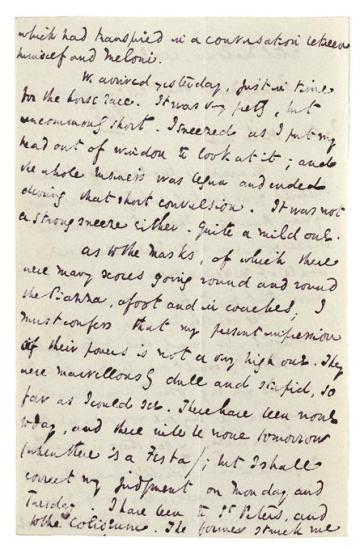

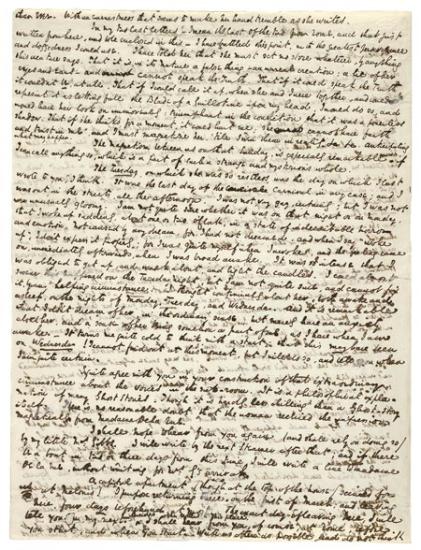

Letter 1 | 30 April 1856 | to Sophie Verena, page 1

Autograph letter signed, Dover, 30 April 1856 to Sophie Verena

Purchased for The Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection as the gift of the Heineman Foundation, 2011

This is an extraordinarily candid and personal letter to the young German novelist Sophie Verena, the pen name of Sophie Alberti, who dedicated her first novel to Dickens. Although it states: "I very seldom write or talk about myself," Dickens's letter describes in detail his physical appearance, exercise regimen, and writing habits. Asked whether he dictates his work, he tells Verena: "I answer with a smile that I can as soon imagine a painter dictating his pictures. No. I write every word of my books with my own hand.... I write with great care and pains (being passionately fond of my art, and thinking it worth any trouble)."

Manuscripts and Letters

The Morgan has the richest collection of Dickens manuscripts and letters in the United States. Dickens's letters are exceptionally brilliant and entertaining, and with his literary manuscripts, provide great insight into his craftsmanship and imagination, giving us the closest view of the novelist at work.

Dickens was careful, methodical, and painstaking in his work. Using a goose quill pen, he generally wrote from ten o'clock each morning until two in the afternoon, completing between two and four pages (or "slips," as he called them) each day. Except for letters, he wrote on only one side of the paper. In his early years, he favored black ink, now faded to brown, but in the late 1840s he switched to blue paper and blue ink, which dried more quickly. The handwriting in his early manuscripts is fluent, bold, and largely free of correction, suggesting "a hand racing to keep pace with the mind's conceptions." But, as he developed as an artist, his handwriting became increasingly small and compact, and his later manuscripts are more heavily revised and complex in appearance.

My Dear Correspondent.

While I was in Paris (which I left only yesterday), I received your book and your charming letter, quite safely. I am grieved to say that I do not read German; but my eldest boy, who has been partly educated in Germany and knows the language well, has gone through your book at my side, and has enabled me to understand much of its pure idea, and fine, womanly, true sentiment. I am proud to be associated with it, and thank you more than ever.

It will take me a year from this time, to finish Little Dorrit. After that, I think I really shall begin (Please God) to make myself master of the German language. I lose so much pleasure by not knowing it, and I can learn a language with so little difficulty, that I often reproach

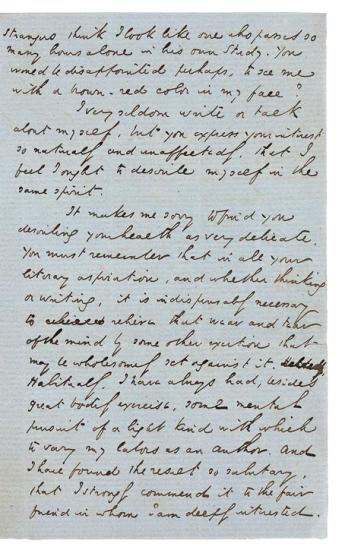

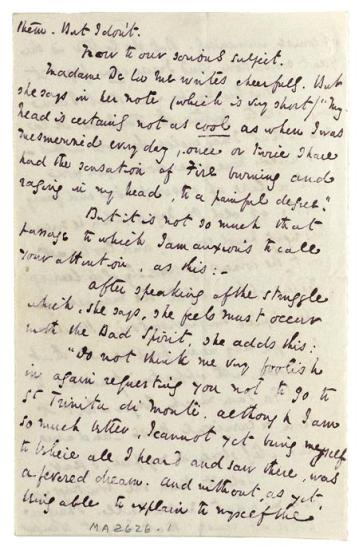

Letter 1 | 30 April 1856 | to Sophie Verena, page 2

Autograph letter signed, Dover, 30 April 1856 to Sophie Verena

Purchased for The Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection as the gift of the Heineman Foundation, 2011

This is an extraordinarily candid and personal letter to the young German novelist Sophie Verena, the pen name of Sophie Alberti, who dedicated her first novel to Dickens. Although it states: "I very seldom write or talk about myself," Dickens's letter describes in detail his physical appearance, exercise regimen, and writing habits. Asked whether he dictates his work, he tells Verena: "I answer with a smile that I can as soon imagine a painter dictating his pictures. No. I write every word of my books with my own hand.... I write with great care and pains (being passionately fond of my art, and thinking it worth any trouble)."

Manuscripts and Letters

The Morgan has the richest collection of Dickens manuscripts and letters in the United States. Dickens's letters are exceptionally brilliant and entertaining, and with his literary manuscripts, provide great insight into his craftsmanship and imagination, giving us the closest view of the novelist at work.

Dickens was careful, methodical, and painstaking in his work. Using a goose quill pen, he generally wrote from ten o'clock each morning until two in the afternoon, completing between two and four pages (or "slips," as he called them) each day. Except for letters, he wrote on only one side of the paper. In his early years, he favored black ink, now faded to brown, but in the late 1840s he switched to blue paper and blue ink, which dried more quickly. The handwriting in his early manuscripts is fluent, bold, and largely free of correction, suggesting "a hand racing to keep pace with the mind's conceptions." But, as he developed as an artist, his handwriting became increasingly small and compact, and his later manuscripts are more heavily revised and complex in appearance.

myself for not having acquired it long ago. I am not so young as I am in the picture you have seen, for that was painted some fifteen years ago, and I am now 44. It looks a good deal, on paper, I find; but I believe I am very young-looking still, and I know that I am a very active vigorous fellow, who never knew in his own experience what the word "fatigue" meant.

This is in answer to your first question. In reply to your second question whether I dictate, I answer with a smile that I can as soon imagine a painter dictating his pictures. No. I write every word of my books with my own hand, and do not write them very quickly either. I write with great care and pains (being passionately fond of my art, and thinking it worth any trouble), and persevere, and work hard. I am a great walker besides, and plunge into cold water every day in the dead of winter. When I was last in Switzerland, I found that I could climb as fast as the Swiss Guides. Few

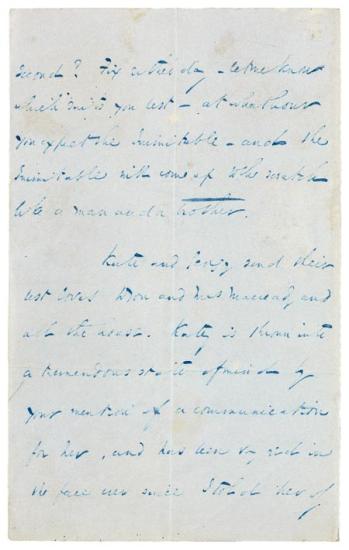

Letter 1 | 30 April 1856 | to Sophie Verena, page 3

Autograph letter signed, Dover, 30 April 1856 to Sophie Verena

Purchased for The Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection as the gift of the Heineman Foundation, 2011

This is an extraordinarily candid and personal letter to the young German novelist Sophie Verena, the pen name of Sophie Alberti, who dedicated her first novel to Dickens. Although it states: "I very seldom write or talk about myself," Dickens's letter describes in detail his physical appearance, exercise regimen, and writing habits. Asked whether he dictates his work, he tells Verena: "I answer with a smile that I can as soon imagine a painter dictating his pictures. No. I write every word of my books with my own hand.... I write with great care and pains (being passionately fond of my art, and thinking it worth any trouble)."

Manuscripts and Letters

The Morgan has the richest collection of Dickens manuscripts and letters in the United States. Dickens's letters are exceptionally brilliant and entertaining, and with his literary manuscripts, provide great insight into his craftsmanship and imagination, giving us the closest view of the novelist at work.

Dickens was careful, methodical, and painstaking in his work. Using a goose quill pen, he generally wrote from ten o'clock each morning until two in the afternoon, completing between two and four pages (or "slips," as he called them) each day. Except for letters, he wrote on only one side of the paper. In his early years, he favored black ink, now faded to brown, but in the late 1840s he switched to blue paper and blue ink, which dried more quickly. The handwriting in his early manuscripts is fluent, bold, and largely free of correction, suggesting "a hand racing to keep pace with the mind's conceptions." But, as he developed as an artist, his handwriting became increasingly small and compact, and his later manuscripts are more heavily revised and complex in appearance.

strangers think I look like one who passes so many hours alone in his own Study. You would be disappointed perhaps, to see me with a brown-red color in my face?

I very seldom write or talk about myself, but you express your interest so naturally and unaffectedly, that I feel I ought to describe myself in the same spirit.

It makes me sorry to find you describing your health as very delicate. You must remember that in all your literary aspiration, and whether thinking or writing, it is indispensably necessary to relieve that wear and tear of the mind by some other exertion that may be wholesomely set against it. Habitually, I have always had, besides great bodily exercise, some mental pursuit of a light kind with which to vary my labors as an Author. And I have found the result so salutary, that I strongly commend it to the fair friend in whom I am deeply interested.

Letter 1 | 30 April 1856 | to Sophie Verena, page 4

Autograph letter signed, Dover, 30 April 1856 to Sophie Verena

Purchased for The Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection as the gift of the Heineman Foundation, 2011

This is an extraordinarily candid and personal letter to the young German novelist Sophie Verena, the pen name of Sophie Alberti, who dedicated her first novel to Dickens. Although it states: "I very seldom write or talk about myself," Dickens's letter describes in detail his physical appearance, exercise regimen, and writing habits. Asked whether he dictates his work, he tells Verena: "I answer with a smile that I can as soon imagine a painter dictating his pictures. No. I write every word of my books with my own hand.... I write with great care and pains (being passionately fond of my art, and thinking it worth any trouble)."

Manuscripts and Letters

The Morgan has the richest collection of Dickens manuscripts and letters in the United States. Dickens's letters are exceptionally brilliant and entertaining, and with his literary manuscripts, provide great insight into his craftsmanship and imagination, giving us the closest view of the novelist at work.

Dickens was careful, methodical, and painstaking in his work. Using a goose quill pen, he generally wrote from ten o'clock each morning until two in the afternoon, completing between two and four pages (or "slips," as he called them) each day. Except for letters, he wrote on only one side of the paper. In his early years, he favored black ink, now faded to brown, but in the late 1840s he switched to blue paper and blue ink, which dried more quickly. The handwriting in his early manuscripts is fluent, bold, and largely free of correction, suggesting "a hand racing to keep pace with the mind's conceptions." But, as he developed as an artist, his handwriting became increasingly small and compact, and his later manuscripts are more heavily revised and complex in appearance.

I am now upon my way home, merely staying here a couple of days to have some walks on the high cliffs by the sea. During the summer, I shall be generally at a little French Country House among pleasant gardens near Boulogne Sur Mer. But that is only a few hours journey from London, and I shall receive my letters and papers from thence, two or three times a week. My best address therefore, is at my own house

Tavistock House

London

— and there I shall always be delighted to hear from you. Perhaps I may see you there one day? If not, I must come to Potsdam after I have learnt German from your book.

Farewell. God bless you! Always believe me, with great regard,

Your affectionate

CHARLES DICKENS

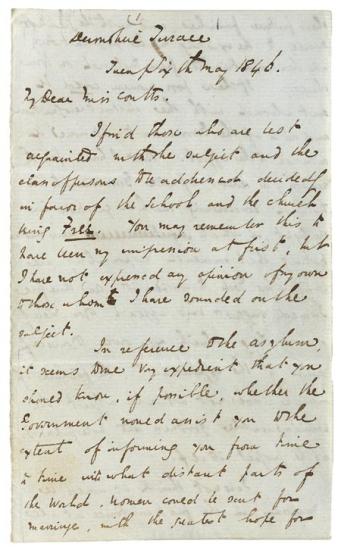

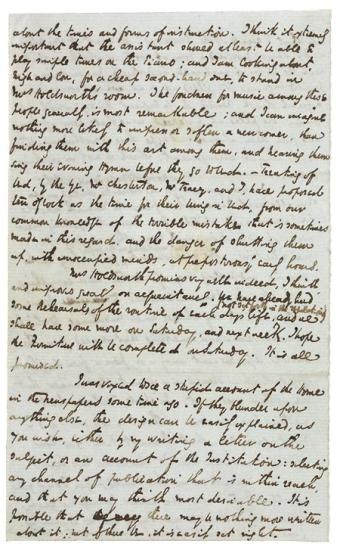

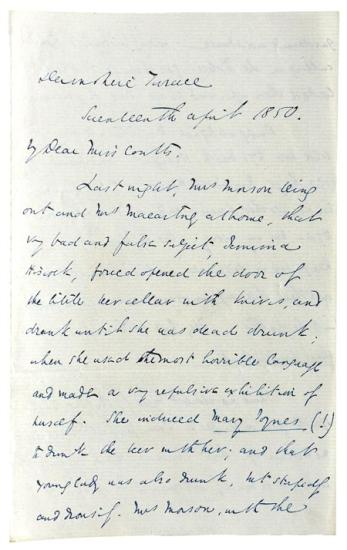

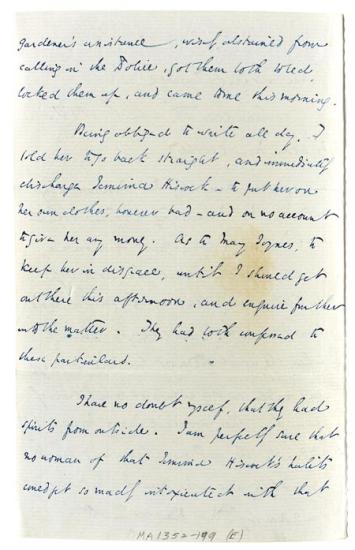

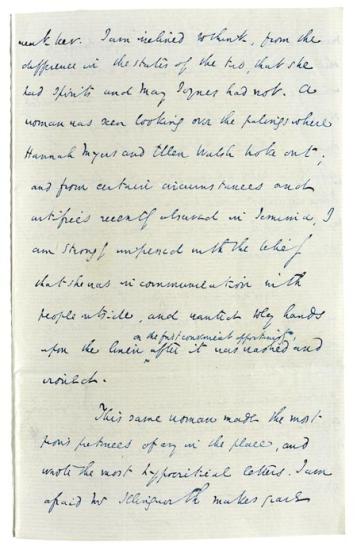

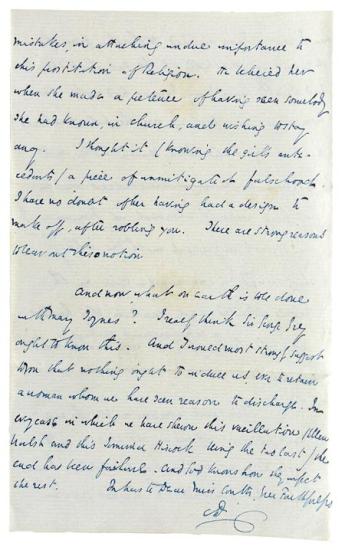

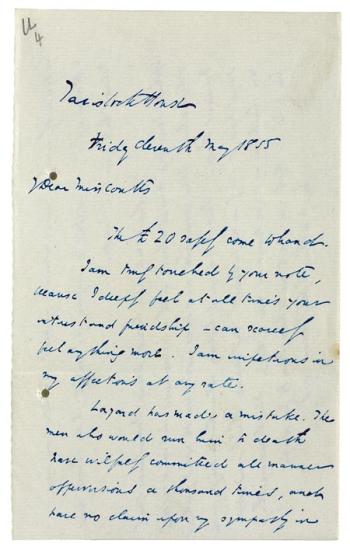

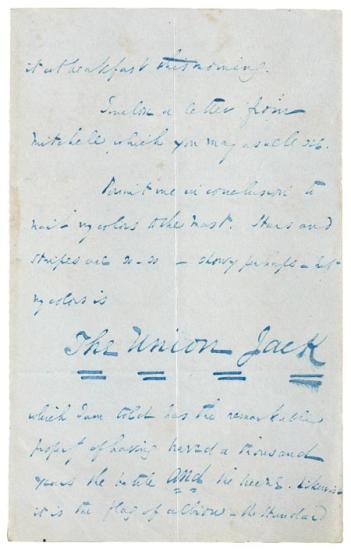

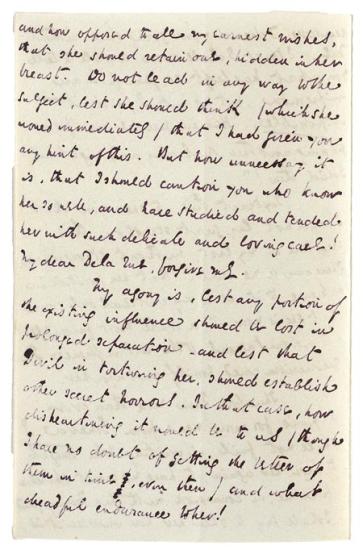

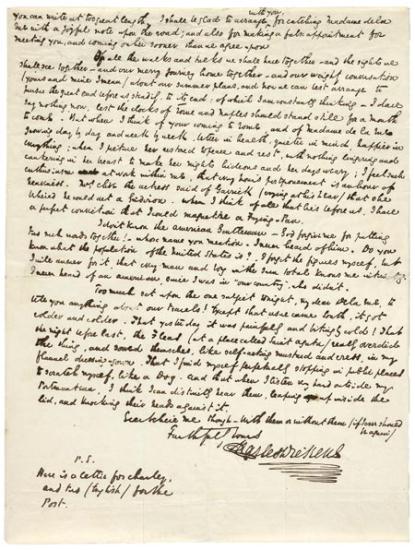

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 1

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

My Dear Miss Coutts.

I find those who are best acquainted with the subject and the class of persons to be addressed, decidedly in favor of the School and the Church being Free. You may remember this to have been my impression at first, but I have not expressed any opinion of my own to those whom I have sounded on the subject.

In reference to the Asylum, it seems to me very expedient that you should know, if possible, whether the Government would assist you to the extent of informing you from time to time into what distant parts of the World, women could be sent for marriage, with the greatest hope for

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 2

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

future families, and with the greatest service to the existing male population, whether expatriated from England or born there. If these poor women could be sent abroad with the distinct recognition and aid of the Government, it would be a service to the effort. But I have (with reason) a doubt of all Governments in England considering such a question in the light, in which men undertaking that immense responsibility, are bound, before God, to consider it. And therefore I would suggest this appeal to you, merely as something which you owe to yourself and to the experiment; the failure of which, does not at all affect the immeasurable goodness and hopefulness of the project itself.

I do not think it would be necessary, in the first instance at all

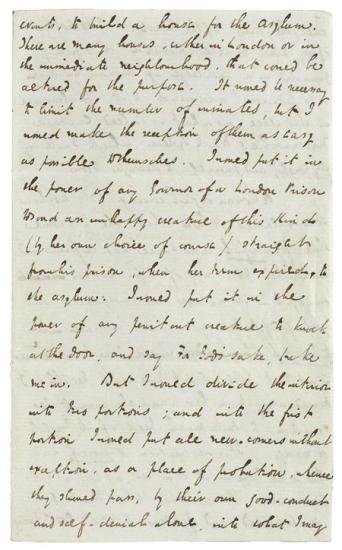

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 3

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

events, to build a house for the Asylum. There are many houses, either in London or in the immediate neighbourhood, that could be altered for the purpose. It would be necessary to limit the number of inmates, but I would make the reception of them as easy as possible to themselves. I would put it in the power of any Governor of a London Prison to send an unhappy creature of this kind (by her own choice of course) straight from his prison, when her term expired, to the Asylum. I would put it in the power of any penitent creature to knock at the door, and say For God's sake, take me in. But I would divide the interior into two portions; and into the first portion I would put all new-comers without exception, as a place of probation, whence they should pass, by their own good-conduct and self-denial alone, into what I may

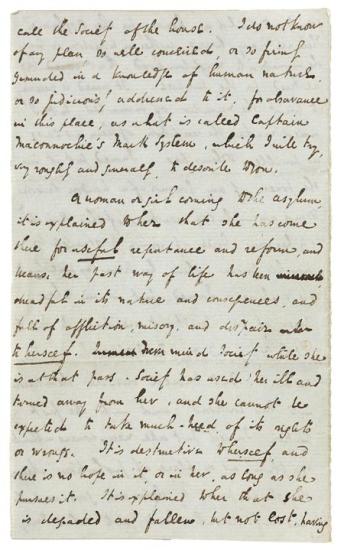

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 4

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

call the Society of the house. I do not know of any plan so well conceived, or so firmly grounded in a knowledge of human nature, or so judiciously addressed to it, for observance in this place, as what is called Captain Maconnochie's Mark System, which I will try, very roughly and generally, to describe to you.

A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs. It is destructive to herself, and there is no hope in it, or in her, as long as she pursues it. It is explained to her that she is degraded and fallen, but not lost, having

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 5

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

this shelter; and that the means of Return to Happiness are now about to be put into her own hands, and trusted to her own keeping. That with this view, she is, instead of being placed in this probationary class for a month, or two months, or three months, or any specified time whatever, required to earn there, a certain number of Marks (they are mere scratches in a book) so that she may make her probation a very short one, or a very long one, according to her own conduct. For so much work, she has so many Marks; for a day's good conduct, so many more. For every instance of ill-temper, disrespect, bad language, any outbreak of any sort or kind, so many—a very large number in proportion to her receipts—are deducted. A perfect Debtor and Creditor account is kept between her and the Superintendent, for every day; and the state of that account, it is in her own power and nobody else's, to adjust to her advantage. It is expressly pointed out to her, that before she can be considered qualified to return to any kind of society—even to the Society of the Asylum—she must give proofs of her power of self-restraint and her sincerity, and her determination to try to shew that she deserves the confidence it is proposed to place in her. Her

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 6

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

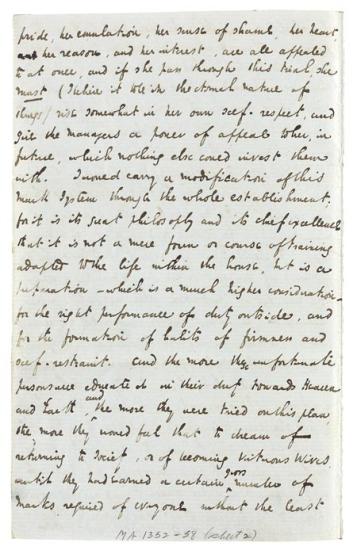

pride, her emulation, her sense of shame, her heart, her reason, and her interest, are all appealed to at once, and if she pass through this trial, she must (I believe it to be in the eternal nature of things) rise somewhat in her own self-respect, and give the managers a power of appeal to her, in future, which nothing else could invest them with. I would carry a modification of this Mark System through the whole establishment; for it is its great philosophy and its chief excellence that it is not a mere form or course of training adapted to the life within the house, but is a preparation—which is a much higher consideration—for the right performance of duty outside, and for the formation of habits of firmness and self-restraint. And the more these unfortunate persons were educated in their duty towards Heaven and Earth, and the more they were tried on this plan, the more they would feel that to dream of returning to Society, or of becoming Virtuous Wives, until they had earned a certain gross number of Marks required of everyone without the least

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 7

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

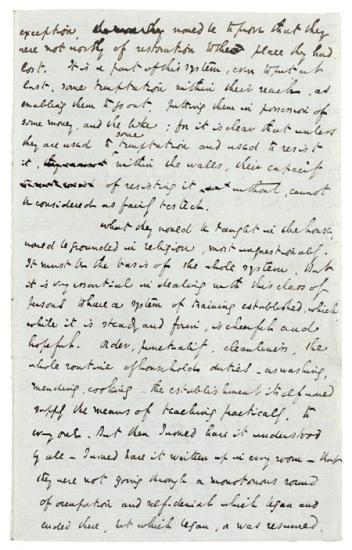

exception, would be to prove that they were not worthy of restoration to the place they had lost. It is a part of this system, even to put at last, some temptation within their reach, as enabling them to go out, putting them in possession of some money, and the like; for it is clear that unless they are used to some temptation and used to resist it, within the walls, their capacity of resisting it without, cannot be considered as fairly tested.

What they would be taught in the house, would be grounded in religion, most unquestionably. It must be the basis of the whole system. But it is very essential in dealing with this class of persons to have a system of training established, which, while it is steady and firm, is cheerful and hopeful. Order, punctuality, cleanliness, the whole routine of household duties—as washing, mending, cooking—the establishment itself would supply the means of teaching practically, to every one. But then I would have it understood by all—I would have it written up in every room—that they were not going through a monotonous round of occupation and self-denial which began and ended there, but which began, or was resumed,

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 8

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

under that roof, and would end, by God's blessing, in happy homes of their own.

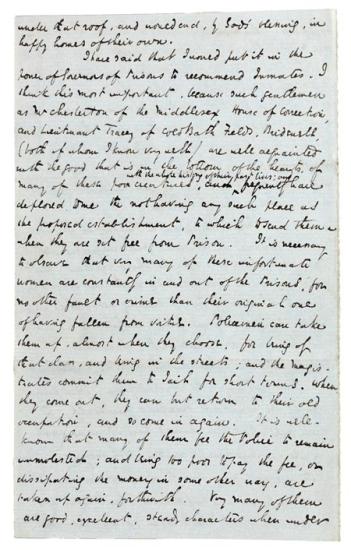

I have said that I would put it in the power of Governors of Prisons to recommend Inmates. I think this most important, because such gentlemen as Mr. Chesterton of the Middlesex House of Correction, and Lieutenant Tracey of Cold Bath Fields, Bridewell, (both of whom I know very well) are well acquainted with the good that is in the bottom of the hearts, of many of these poor creatures, and with the whole history of their past lives; and frequently have deplored to me the not having any such place as the proposed establishment, to which to send them—when they are set free from Prison. It is necessary to observe that very many of these unfortunate women are constantly in and out of the Prisons, for no other fault or crime than their original one of having fallen from virtue. Policemen can take them up, almost when they choose, for being of that class, and being in the streets; and the Magistrates commit them to Jail for short terms. When they come out, they can but return to their old occupation, and so come in again. It is well-known that many of them fee the Police to remain unmolested; and being too poor to pay the fee, or dissipating the money in some other way, are taken up again, forthwith. Very many of them are good, excellent, steady characters when under

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 9

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

restraint—even without the advantage of systematic training, which they would have in this Institution—and are tender nurses to the sick, and are as kind and gentle as the best of women.

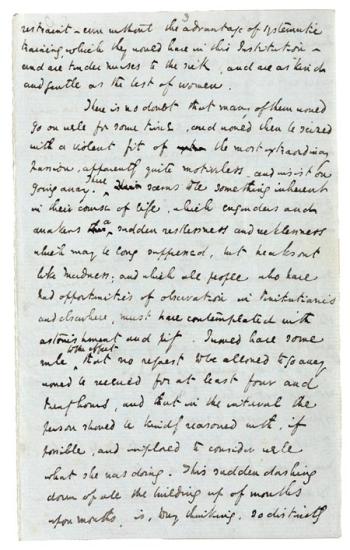

There is no doubt that many of them would go on well for some time, and would then be seized with a violent fit of the most extraordinary passion, apparently quite motiveless, and insist on going away. There seems to be something inherent in their course of life, which engenders and awakens a sudden restlessness and recklessness which may be long suppressed, but breaks out like Madness; and which all people who have had opportunities of observation in Penitentiaries and elsewhere, must have contemplated with astonishment and pity. I would have some rule to the effect that no request to be allowed to go away would be received for at least four and twenty hours, and that in the interval the person should be kindly reasoned with, if possible, and implored to consider well what she was doing. This sudden dashing down of all the building up of months upon months, is, to my thinking, so distinctly

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 10

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

a Disease with the persons under consideration that I would pay particular attention to it, and treat it with particular gentleness and anxiety; and I would not make one, or two, or three, or four, or six departures from the Establishment a binding reason against the readmission of that person, being again penitent, but would leave it to the Managers to decide upon the merits of the case: giving very great weight to general good conduct within the house.

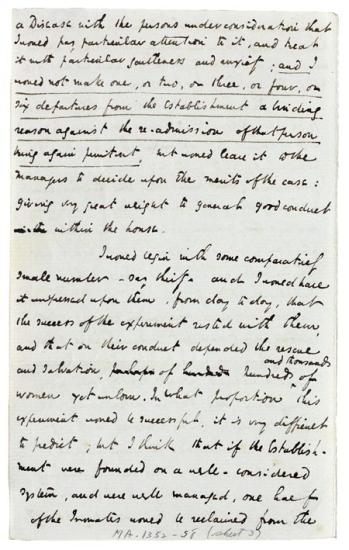

I would begin with some comparatively small number—say thirty—and I would have it impressed upon them, from day to day, that the success of the experiment rested with them, and that on their conduct depended the rescue and salvation, of hundreds and thousands of women yet unborn. In what proportion this experiment would be successful, it is very difficult to predict; but I think that if the Establishment were founded on a well-considered system, and were well managed, one half of the Inmates would be reclaimed from the

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 11

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

very beginning, and that after a time the proportion would be very much larger. I believe this estimate to be within very reasonable bounds.

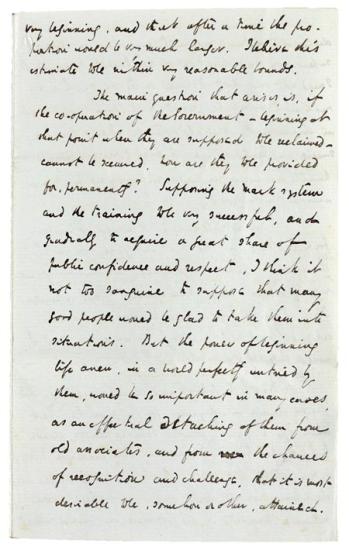

The main question that arises, is, if the co-operation of the Government—beginning at that point when they are supposed to be reclaimed—cannot be secured, how are they to be provided for, permanently? Supposing the mark system and the training to be very successful, and gradually to acquire a great share of public confidence and respect, I think it not too sanguine to suppose that many good people would be glad to take them into situations. But the power of beginning life anew, in a world perfectly untried by them, would be so important in many cases, as an effectual detaching of them from old associates, and from the chances of recognition and challenge, that it is most desirable to be, somehow or other, attained.

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 12

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

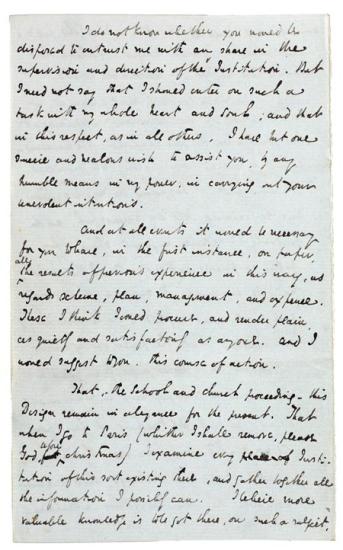

I do not know whether you would be disposed to entrust me with any share in the supervision and direction of the Institution. But I need not say that I should enter on such a task with my whole heart and soul; and that in this respect, as in all others, I have but one sincere and zealous wish to assist you, by any humble means in my power, in carrying out your benevolent intentions.

And at all events it would be necessary for you to have, in the first instance, on paper, all the results of previous experience in this way, as regards scheme, plan, management, and expence. These I think I could procure, and render plain, as quietly and satisfactorily as anyone. And I would suggest to you, this course of action.

That,—the School and Church proceeding—this Design remain in abeyance for the present. That when I go to Paris (whither I shall remove, please God, before Christmas) I examine every Institution of this sort existing there, and gather together all the information I possibly can. I believe more valuable knowledge is to be got there, on such a subject,

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 13

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

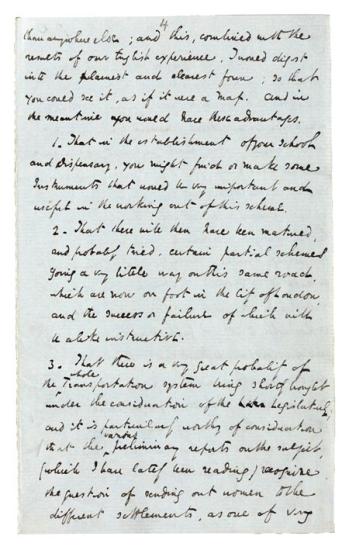

than anywhere else; and this, combined with the results of our English experience, I would digest into the plainest and clearest form; so that you could see it, as if it were a Map. And in the meantime you would have these advantages.

1. That in the establishment of your school and Dispensary, you might find or make some Instruments that would be very important and useful in the working out of this scheme.

2. That there will then have been matured, and probably tried, certain partial schemes going a very little way on this same road, which are now on foot in the City of London, and the success or failure of which will be alike instructive.

3. That there is a very great probability of the whole Transportation system being shortly brought under the consideration of the Legislature; and it is particularly worthy of consideration that the various preliminary reports on the subject, (which I have lately been reading) recognize the question of sending out women to the different settlements, as one of very

Letter 2 | 26 May 1846 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 14

Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

great importance.

I have that deep sense, dear Miss Coutts, of the value of your confidence in such a matter, and of the pure, exalted, and generous motives by which you are impelled, that I feel a most earnest anxiety that such an effort as you contemplate in behalf of your Sex, should have every advantage in the outset it can possibly receive, and should, if undertaken at all, be undertaken to the lasting honor of your name and Country. In this feeling, I make the suggestion I think best calculated to promote that end. Trust me, if you agree in it, I will not lose sight of the subject, or grow cold to it, or fail to bestow upon it my best exertions and reflection. But, if there be any other course you would prefer to take; and you will tell me so; I shall be as devoted to you in that as in this, and as much honored by being asked to render you the least assistance.

Ever Faithfully Yours

CD.

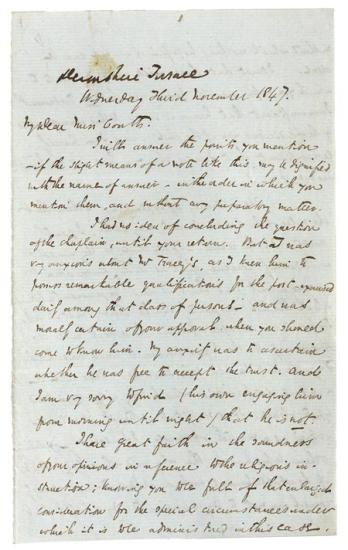

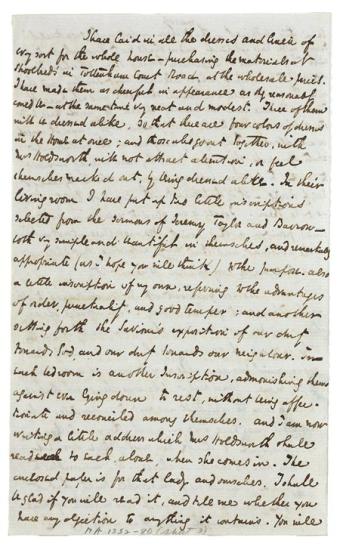

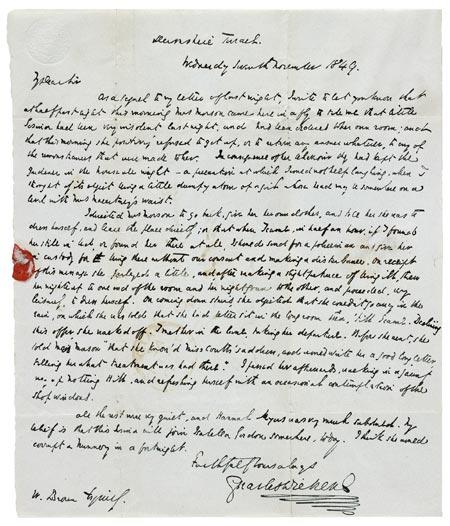

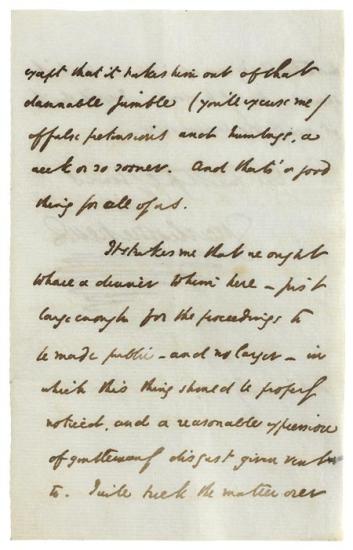

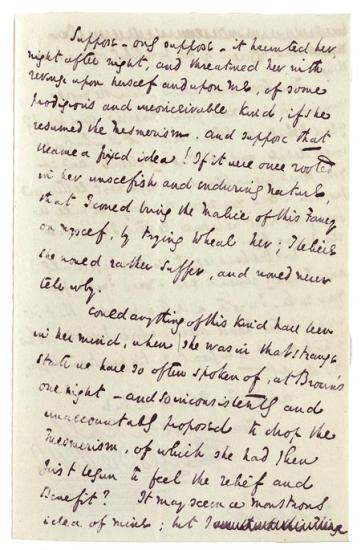

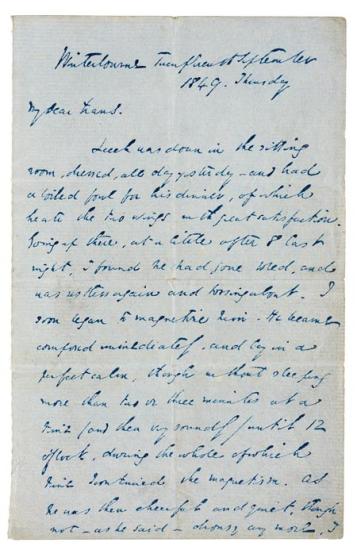

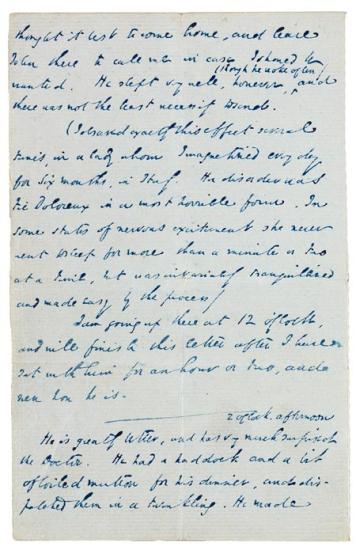

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 1

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

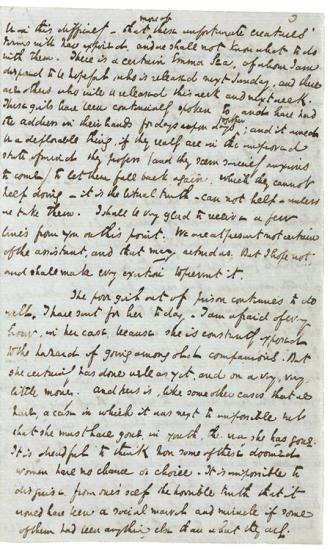

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

My Dear Miss Coutts.

I will answer the points you mention—if the slight means of a note like this may be dignified with the name of answer—in the order of which you mention them, and without any preparatory matter.

I had no idea of concluding the question of the chaplain, until your return. But I was very anxious, about Mr. Tracey's, as I knew him to possess remarkable qualifications for the post—exercised daily among that class of persons—and was morally certain of your approval when you should come to know him. My anxiety was to ascertain whether he was free to accept the trust. And I am very sorry to find (his own engaging him from morning until night) that he is not.

I have great faith in the soundness of your opinions in reference to the religious instruction; knowing you to be full of that enlarged consideration for the special circumstances under which it is to be administered in this case,

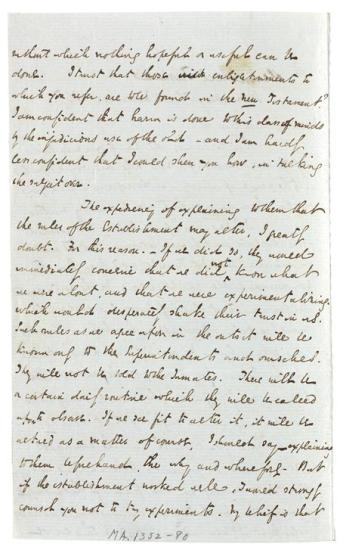

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 2

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

without which nothing hopeful or useful can be done. I trust that those enlightenments to which you refer, are to be found in the New Testament? I am confident that harm is done to this class of minds by the injudicious use of the old—and I am hardly less confident that I could shew you how, in talking the subject over.

The expediency of explaining to them that the rules of the Establishment may alter, I greatly doubt. For this reason.—If we did so, they would immediately conceive that we did not know what we were about, and that we were experimentalizing. Which would desperately shake their trust in us. Such rules as we agree upon in the outset will be known only to the Superintendents and ourselves. They will not be told to the Inmates. There will be a certain daily routine which they will be called upon to observe. If we see fit to alter it, it will be altered as a matter of course, I should say—explaining to them beforehand, the why and wherefore. But, if the establishment worked well, I would strongly counsel you not to try experiments. My belief is, that

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 3

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

nothing would unsettle them so much, or render their staying with us so doubtful.—Recollect that we address a peculiar and strangely-made character.

There is this objection to the address of the chaplain to each person individually.—It would decidedly involve the risk of their refusing to come to us. The extraordinary monotony of the Refuges and Asylums now existing, and the almost insupportable extent to which they carry the words and forms of religion, is known to no order of people as well as to these women; and they have that exaggerated dread of it, and that preconceived sense of their inability to bear it, which the reports of those who have refused to stay in them, have bred in their minds. I am afraid if they were thus taken to task, and especially by a clergyman, they would be alarmed—would say "its the old story after all, and we have mistaken the sort of place. It's better to say at once that we are not fit for it"—and that so we should lose them. That they are sensible of the sinfulness and degradation of their lives—

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 4

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

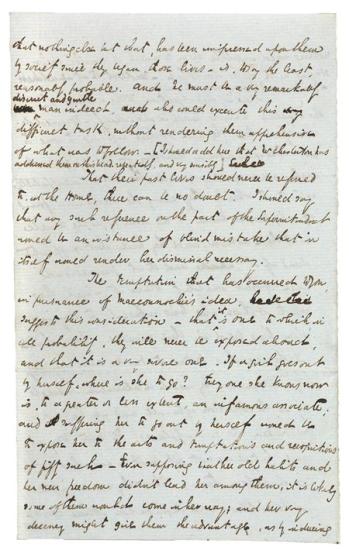

that nothing else but that, has been impressed upon them by society since they began those lives—is, to say the least, reasonably probable. And he must be a very remarkably discreet and gentle man indeed, who could execute this very difficult task, without rendering them apprehensive of what was to follow.—[I should add here that Mr. Chesterton has addressed them on this head, repeatedly, and very sensibly.]

That their past lives should never be referred to, at the Home, there can be no doubt. I should say that any such reference on the part of the Superintendent would be an instance of blind mistake that in itself would render her dismissal necessary.

The temptation that has occurred to you, in pursuance of Macconnochie's idea, suggests this consideration—that it is one to which in all probability, they will never be exposed abroad, and that it is a very severe one. If a girl goes out by herself, where is she to go? Every one she knows now is, to a greater or less extent, an infamous associate; and suffering her to go out by herself would be to expose her to the arts and temptations and recognitions of fifty such—Even supposing that her old habits and her new freedom didn't lead her among them, it is likely some of them would come in her way; and her very decency might give them the advantage, as by inducing

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 5

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

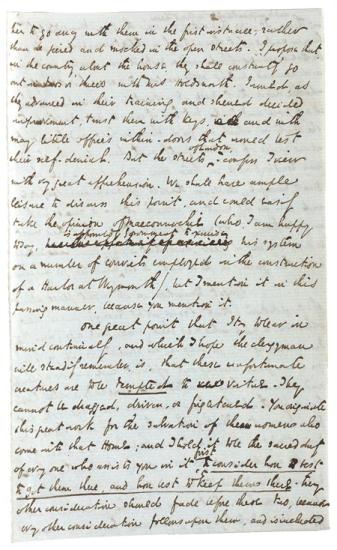

that nothing else but that, has been impressed upon them by society since they began those lives—is, to say the least, reasonably probable. And he must be a very remarkably discreet and gentle man indeed, who could execute this very difficult task, without rendering them apprehensive of what was to follow.—[I should add here that Mr. Chesterton has addressed them on this head, repeatedly, and very sensibly.]

That their past lives should never be referred to, at the Home, there can be no doubt. I should say that any such reference on the part of the Superintendent would be an instance of blind mistake that in itself would render her dismissal necessary.

The temptation that has occurred to you, in pursuance of Macconnochie's idea, suggests this consideration—that it is one to which in all probability, they will never be exposed abroad, and that it is a very severe one. If a girl goes out by herself, where is she to go? Every one she knows now is, to a greater or less extent, an infamous associate; and suffering her to go out by herself would be to expose her to the arts and temptations and recognitions of fifty such—Even supposing that her old habits and her new freedom didn't lead her among them, it is likely some of them would come in her way; and her very decency might give them the advantage, as by inducing

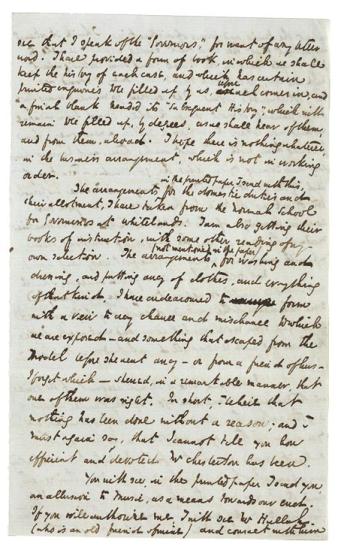

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 6

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

in them, and is impracticable without them. It is for this vital reason that a knowledge of human nature as it shews itself in these tarnished and battered images of God—and a patient consideration for it—and a determined putting of the question to one's self, not only whether this or that piece of instruction or correction be in itself good and true, but how it can be best adapted to the state in which we find these people, and the necessity we are under of dealing gently with them, lest they should run headlong back on their own destruction—are the great, merciful, Christian thoughts for such an enterprize, and form the only spirit in which it can be successfully undertaken. Do you not feel, with me, that this must be kept steadily in view, and that a chaplain imbued with this feeling in the outset, is the only Minister for this place?

I forgot to mention in its right place, about the temptation, that I saw, at Mr. Tracey's prison the other day, a girl who was there, some time ago (merely, if I remember right, for being in the streets, or, if for felony for some offence arising out of that life) whose appearance and behaviour had so interested some lady or other, living hard by, that when her term was over, she took her for a servant. That girl, although she had the reputation of being a drunkard, worked hard and honestly in this employment for seven or eight months, and had wine and spirits constantly in her keeping, which she never touched. But in an evil hour her Mistress gave her a holiday. She fell among her old companions

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 7

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

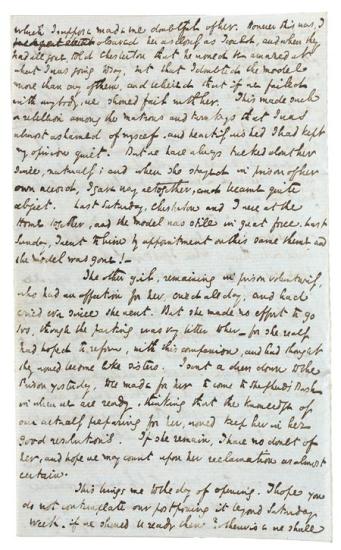

—her removal from whom had been the main cause of her reformation, poor creature—never went back again, fell into her old way of life, and is in prison now. I saw her with Mr. Chesterton, and talked to her, but thought it best to decline her: for besides the danger of her attachment to liquor (though I do not, like Mr. Chesterton: neither does Mr. Tracey attach overwhelming importance to that, in a young woman of that way of life, who drinks because she is utterly miserable—a middle aged woman who drinks, is another thing, and is always hopeless) she had a singularly bad head, and looked discouragingly secret and moody.

I must tell you of one of the two young women who were remaining in Prison voluntarily, until we could take them. When I first went there, about your home, she was produced to me by Mr. Chesterton, before I saw any of the others, as a model. She was the Matron's model, and the head female turnkey's model, and the peculiar pet and protegée of Mr. Rotch the Magistrate, who is a very good man, and takes infinite pains in the prisons—though I doubt his understanding of the company he finds there. She was much better educated than any of the others (some of whom are extremely ignorant), had a very intelligent face, and a remarkably good voice; but she impressed me as being something too grateful, and too voluble in her earnestness, and she seemed, in a vague, indescribable, uneasy way, to be doubtful of me.

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 8

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951