PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE: Ray Johnson Photographs

Dubbed “New York’s most famous unknown artist” by the New York Times, Ray Johnson (1927–1995) was a widely connected downtown figure, Pop art innovator, and pioneer of collage and mail art. After moving from Manhattan to suburban Long Island in 1968, Johnson selectively distanced himself from the mainstream art world, holding only two exhibitions after 1978. Yet even after his last show, in 1991, he remained a prolific and unpredictable artist.

Johnson used photographs in his work for decades, but it was only with his purchase of a single-use, point-and-shoot camera in January 1992 that he embarked on his own “career as a photographer.” By the end of December 1994 he had used 137 disposable cameras. His most frequent subjects were what he called his Movie Stars: meter-high collages on cardboard, often featuring the bunny head that served as his artistic signature. They became ensemble players in the curious tableaux he staged in everyday locales near his Locust Valley home.

At his death by suicide in January 1995, Johnson left a vast archive of art in boxes stacked throughout his house, including over five thousand color photographs, still in the envelopes from the developer’s shop. This body of work, virtually unseen until now, comprised his final major art project, the last act in a romance with photography that had begun some forty years earlier.

PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE: Ray Johnson Photographs is made possible by Ronay and Richard L. Menschel and the J. W. Kieckhefer Foundation, with support from the Young Fellows of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Unless otherwise noted, all works are by Ray Johnson. Johnson did not title his photographs; descriptive titles are provided for identification purposes only.

Overview

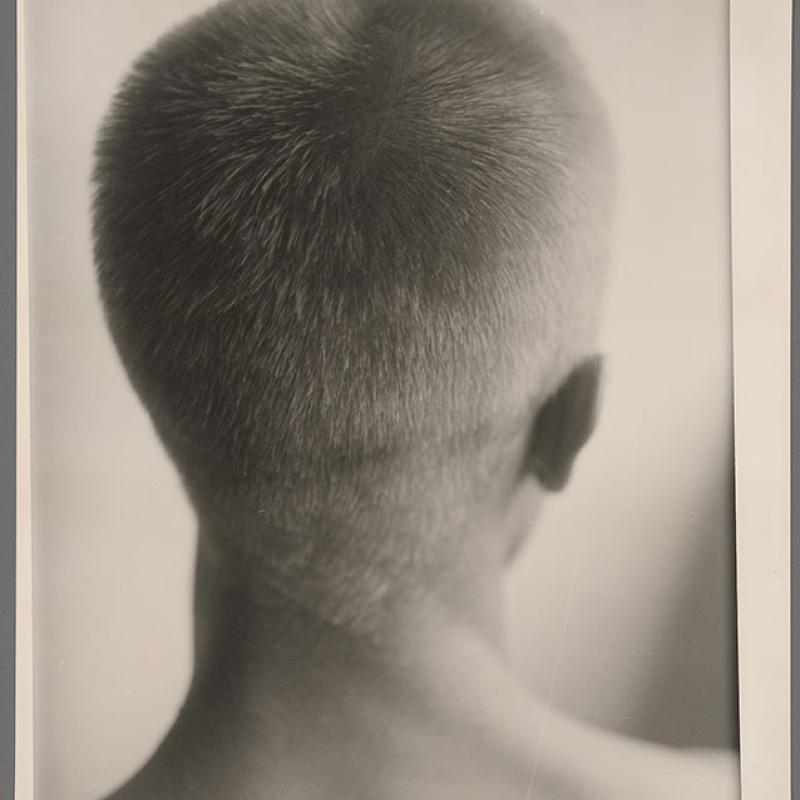

Ray Johnson at Black Mountain College

As a student at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College from 1945 to 1948, Johnson thrived under the rigorous tutelage of his foundation-course teacher Josef Albers (1888–1976). Johnson also modeled for Archer, a fellow student who would go on to teach photography at the school. This portrait—lush, faceless, and sexually ambiguous—foreshadows the complexity of Johnson’s use of photography throughout his career. Though attracted by the camera’s peerless ability to bestow glamour, he often tried to undercut its role as a transparent conveyor of facts.

Hazel Larsen Archer

American, 1921–2001

Ray Johnson at Black Mountain College

1948

Gelatin silver print

13 3/4 × 9 7/8 inches

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased as the gift of David Dechman and Michel Mercure, 2021.56

© Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer

RJ silhouette and wood, Stehli Beach

As an artist, Johnson was a master hunter-recycler, constantly revisiting and reinterpreting images from his past. On a visit to the beach at nearby Oyster Bay in 1992, he brought along a camera and a cardboard cutout of his head. Propping the board against a piece of driftwood log, he created a visual pun: the log’s central rings evoke the swirl of hair that Hazel Archer had once photographed on his (now long-bald) head.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

RJ silhouette and wood, Stehli Beach

autumn 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:43

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

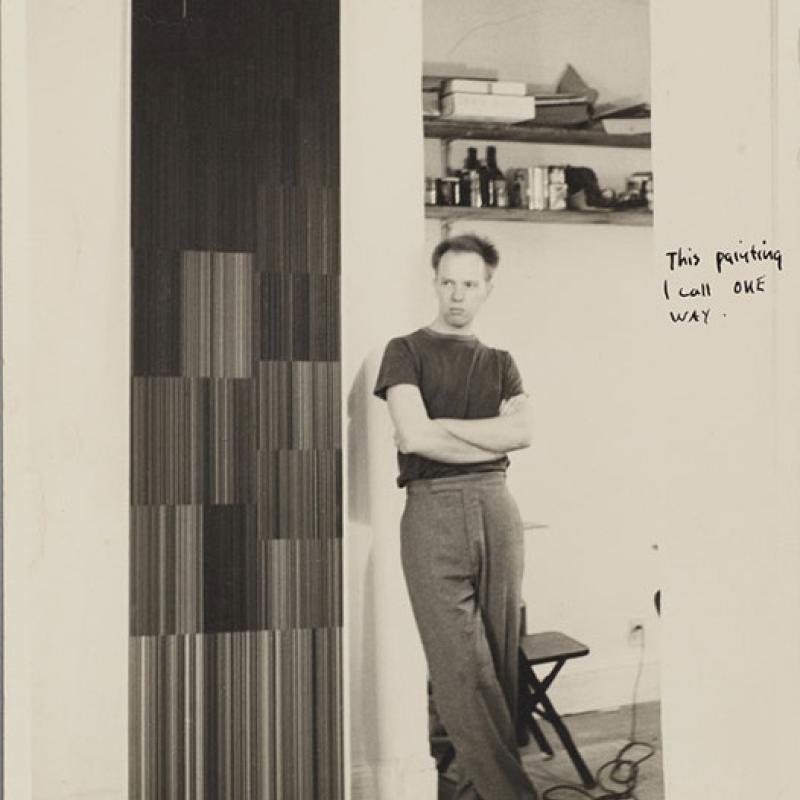

Ray Johnson with "One Way"

In this photograph, which Johnson mailed to a friend, he poses in his studio in New York City, where he moved after completing his studies at Black Mountain College. During his early years in the city, Johnson focused on abstract painting. In the mid-1950s, however, he would decisively shift his efforts to producing the small, irregularly shaped collages he called moticos. Johnson’s teacher Josef Albers had advised ambitious students to destroy their formative work when they felt ready to move on. Johnson burned every canvas still in his possession, including One Way, but traces of his early development survive in photographs such as this one.

Rudy Burckhardt

American, born in Switzerland, 1914–1999

Ray Johnson with "One Way"

ca. 1948–52

Gelatin silver print

7 1/2 × 5 1/2 in. (19.05 × 13.97 cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© 2022 Rudy Burckhardt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York DO NOT USE UNTIL PERMISSION IS CLEARED

Untitled (Moticos with KAFKAYLLA)

Johnson applied one all-purpose noun, “moticos” (both singular and plural), to his short writings, his collages, and the glyph-like shapes he drew. He and his friend Norman Solomon coined the term by reshuffling the word “osmotic,” chosen out of the dictionary. On this moticos made from a flattened box, Johnson paired a photograph of a pigeon with its strange twin: a sort of photo-bird, composed of cookie cutters and a checkerboard. Johnson proposes a second unlikely duo by combining the names of the author Franz Kafka (1883–1924) and the photographer Ylla (Camilla Koffler, 1911–1955), known for her images of animals.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Moticos with KAFKAYLLA)

ca. 1953–54

Collage on illustration board

13 × 5 in. (33.02 × 12.7 cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Untitled (James Dean in the Rain)

From the early 1950s, Johnson embraced photocollage as a way to inject Hollywood glamour into the cloistered world of avant-garde art. He was appropriating mass-media imagery years before Andy Warhol began populating monumental canvases with celebrity portraits. Here Johnson worked directly upon Dennis Stock’s iconic Life magazine photograph of James Dean walking alone through Times Square, which was published a few months before Dean died in a 1955 car crash. Whether Johnson made this work before or after Dean’s death is unknown. In the 1990s, he would again incorporate the actor’s silhouette in collages and photographs.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (James Dean in the Rain)

ca. 1953–59

Collage on illustration board

15 1/2 × 11 3/4 in. (39.37 × 29.85 cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Untitled (Moticos on floor)

For a short feature in the first issue of the Village Voice (26 October 1955), a reporter walked with Johnson as he approached strangers in Grand Central Terminal and asked them whether they knew what a “moticos” was. As seen here, Johnson also literally took moticos to the streets, staging crowds of them for the camera in disused spaces in downtown Manhattan. Few early moticos have survived intact: over the next several decades, in a practice he called Chop art, Johnson continually disassembled his work and used the fragments to create new pieces.

Elisabeth Novick

Untitled (Moticos on floor)

ca. 1955

Gelatin silver print

8 3/4 × 13 1/4 inches

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of

Frances Beatty; 2022.3:2

Elisabeth Loewenstein / ArenaPAL

© Elisabeth Loewenstein

A performance preserved

In 1955 Johnson asked his friend Elisabeth Loewenstein (later Novick) to bring a camera along on a walk with their mutual friend Suzi Gablik (1934–2022). Novick’s photographs record the impromptu performance that ensued, in which Johnson draped moticos on Gablik’s face and body. A fellow Black Mountain College alum, Gablik would become an influential critic; in her 1969 book on Pop art, she described improvised actions such as this one as the first “informal happenings”—ephemeral events conceived as works of art—in the postwar era.

Johnson preserved the photographs Novick made that day. Nearly forty years later, in one of his earliest experiments with a “throwaway camera,” he laid out the prints in a grid on his driveway and photographed them from atop a ladder.

Elisabeth Novick

Untitled (Ray Johnson and Suzi Gablik)

1955

Gelatin silver print

11 × 14 inches

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of

Frances Beatty; 2022.3:3

Elisabeth Loewenstein / ArenaPAL

© Elisabeth Loewenstein

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

1955 moticos photographs from ladder

January 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:53

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

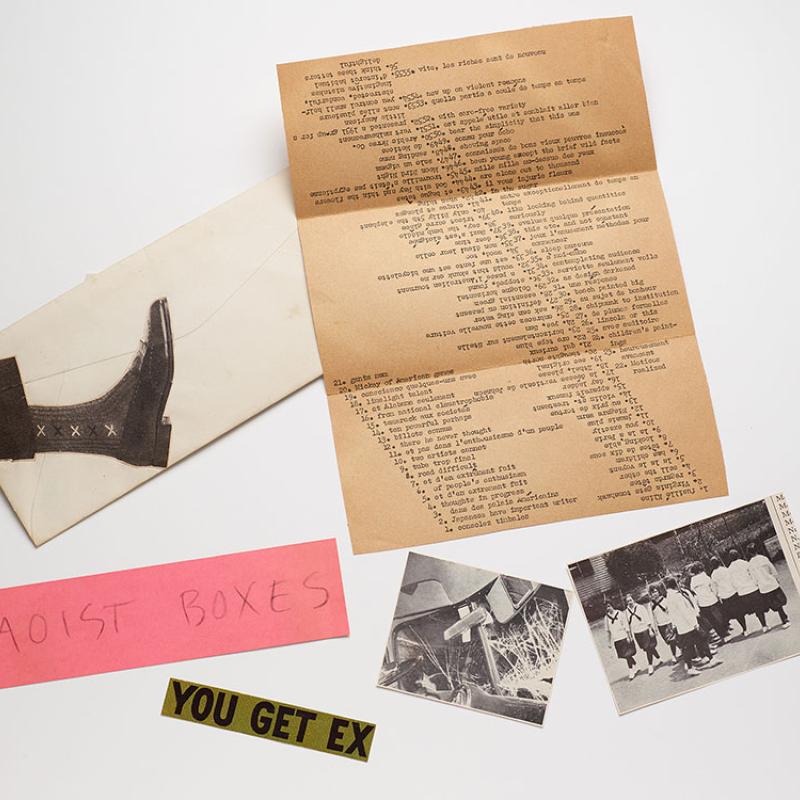

Correspondence to Frances X. Profumo

In the mid-1950s, Johnson simultaneously shifted from oil painting to small-scale collage and from gallery exhibitions to the mail as a way of putting his art before an individual viewer. An envelope from Johnson often contained enigmatic clippings from books and magazines, including photographic illustrations drawn from the same stockpile that fueled his collages. These are items Johnson sent in the 1950s to Frances X. Profumo, whom he befriended when he was a student and she an employee at Black Mountain College. The many visual and textual Xs invoke both Profumo’s distinctive middle initial and the convention of signing a fond letter “with kisses” (XXX).

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Correspondence to Frances X. Profumo

Undated

Typewritten text on paper, newspaper clippings

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photographic correspondences

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Nothing with Brancusi)

Undated

Ink on book page

9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24.13 × 19.05 cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Mapplethorpe with moticos)

Undated

Ink on magazine page

Image: 7 × 7 in. (17.78 × 17.78 cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (book page with umbrella as splint)

Undated

Ink on paper

Image: 9 1/2 × 7 in. (24.13 × 17.78 cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

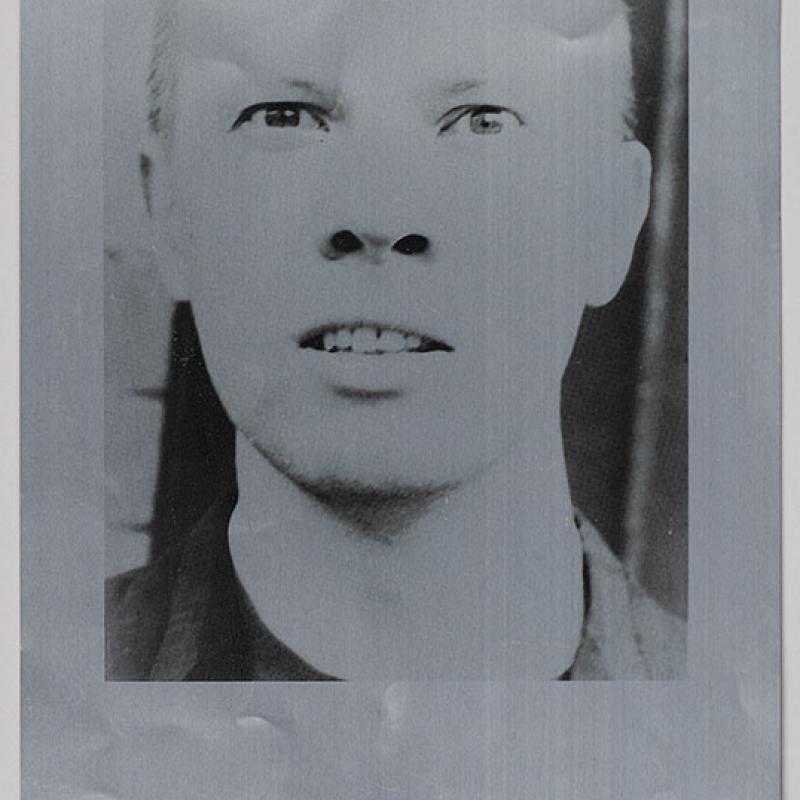

An unnerving likeness

Johnson favored likenesses that masked as much about him as they revealed. He repeatedly used a headshot that his friend Ara Ignatius made around 1963. It is an unnerving image, lacking the conceit of intimacy that characterizes most formal portraits; instead it “stands for” Johnson, in the artless manner of a government-issued ID.

Many pieces of mail art that look like photocopies are in fact products of offset printing—a means of transferring photographs and other images to the page from reusable metal plates. The medium allowed Johnson to return to an image repeatedly, imposing variations that reflected his ever-changing purposes.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Offset printing plate (Ara Ignatius portrait)

ca. 1964

Metal

Image: 15 1/2 × 10 in. (39.37 × 25.4 cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Ara Ignatius portrait with a photograph of lips)

Undated

Cut paper on paper

Image: 11 × 8 1/2 in. (27.94 × 21.59 cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Ara Ignatius portrait with bunnyheads)

Undated

Ink on paper

Image: 11 × 8 1/2 in. (27.94 × 21.59 cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Untitled ("I shot an arrow into the air..." with Shirley Temple and Vikki Dougan)

In this photocollage, two movie actors meet: Vikki Dougan (b. 1929), who became a sex symbol in the 1950s by publicly appearing in backless dresses, and the quintessentially innocent child star Shirley Temple (1928–2014). Temple’s rendering as a blacked-out, moticos-like figure may allude to her adult married name, Shirley Temple Black. Across the bottom of the image, a line from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1845 poem “The Arrow and the Song” is altered to refer to Johnson’s forerunner in collage and assemblage art, Joseph Cornell (1903–1972), who lived in Flushing, Queens.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled ("I shot an arrow into the air..." with Shirley Temple and Vikki Dougan)

ca. 1970–72

Ink, wash, collage, vintage photograph on illustration board

18 × 15 in. (45.72 × 38.1 cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

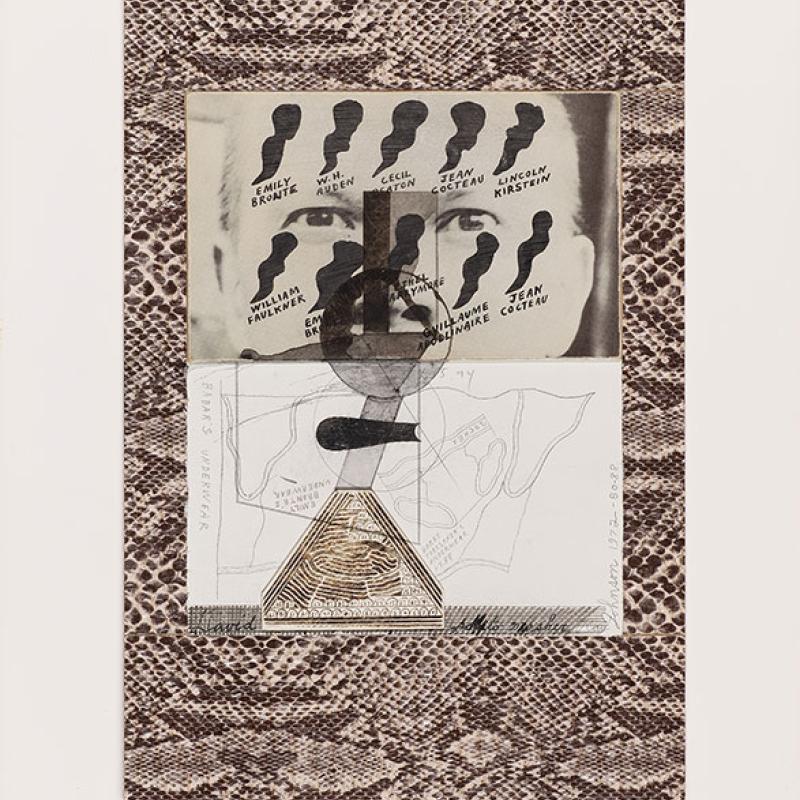

David Hockney's Mother's Potato Masher

The title of each collage in the Potato Masher series begins with a notable artist’s or celebrity’s name. The titles then take an abrupt turn away from stardom by alluding first to the famed figure’s mother, and then to her potato masher. Here, Johnson included his own likeness in the form of a headshot, made around 1963 by the photographer Ara Ignatius. His face is covered by black moticos and cut-up fragments of his earlier artworks. Johnson created his collages over a span of weeks, months, or even years, dating each element in pencil as it joined the composition.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

David Hockney's Mother's Potato Masher

1972–80–88–94

Collage on cardboard panel

20 3/8 × 15 1/4 in. (51.75 × 38.74 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Frances Beatty, Alexander Adler, and the Ray Johnson Estate; 2022.3:1

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Untitled (Photo Booth Collage)

Here, Johnson (visible at top left) employs a booth as an affordable studio for documenting works from his Potato Masher series. Sitting in the photo booth, he simply held up one collage after another for the automatic camera. The resulting sequence of vertical photo strips combines the qualities of a crude performance document and an art gallery’s inventory sheet. David Hockney’s Mother’s Potato Masher appears, not yet finished, fourth from the left in the bottom row.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Photo Booth Collage)

1972

Collage on illustration board

12 7/8 × 19 in. (32.7 × 48.26 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Frances Beatty, Alexander Adler, and the Ray Johnson Estate; 2022.3:3

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo booth self-portraits

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A Tab is a Bill

In 1976 Johnson began asking friends, art-world figures, and celebrities to sit and have their silhouettes traced onto paper. He thus built a library of nearly three hundred profile templates he could use and reuse. As a portrait form, the silhouette reduces its subject to a graphic shape, identifiable but resistant to psychological interpretation. In this example, Johnson overlapped the profiles of 1950s movie heartthrob Tab Hunter (1931–2018) and avantgarde writer William S. Burroughs (1914–1997).

In the 1990s Johnson photographed one of his stock props, a stuffed kingfisher, in combination with Burroughs’s silhouette. The beak of the bird extends the author’s prominent nose: a bill replacing the bill of a Bill.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Tab Hunter William Burroughs)

ca. 1976–81

Collage on cardboard panel

12 × 12 1/2 in. (30.48 × 31.75 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Frances Beatty, Allen Adler,

Alexander Adler, and the Ray Johnson Estate; 2022.3:2

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

William S. Burroughs silhouette and kingfisher

winter 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum, gifts of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy

of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:8

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

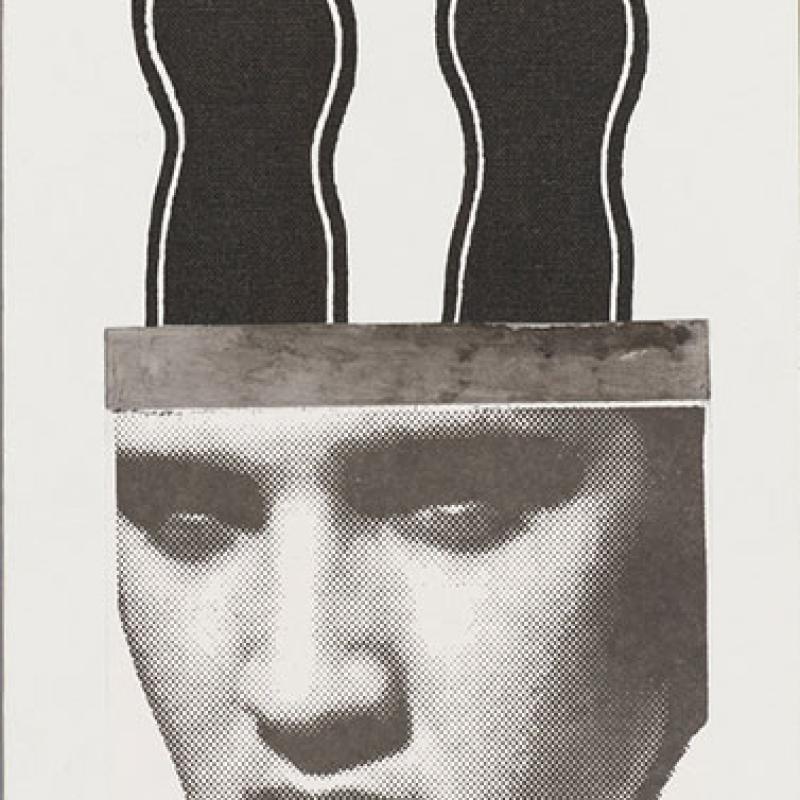

Untitled (Elvis with Bunny Ears)

Beginning in the 1950s, Johnson made artistic use of photographs of the twentieth-century cultural icon Elvis Presley (1935–1977). Johnson’s most emblematic motif, a stylized bunny face, first appeared beside the artist’s name in 1964. Bunny ears would serve both as a kind of trademark and as a way of turning anyone—Elvis, in this case—into a Ray Johnson character. The enlarged halftone dots that compose Elvis’s image confirm its status as a mass-market photographic reproduction.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Elvis with Bunny Ears)

1987

Collage with acrylic and ink on canvasboard

16 × 8 in. (40.64 × 20.32 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty.

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A new career

Johnson appears to have first used a disposable camera for a practical purpose: documenting his backlog of unused collage fragments. But in January 1992, he told curator Clive Phillpot, “I’m pursuing my career as a photographer,” and in March he added, “I’m having fun with my throw-away camera.” Always faithful to the rapidity of his own thinking, Johnson found in the “throwaway” Fuji Quicksnap a way to give graphic form to ideas as they occurred to him.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Rubble and photo credit

summer 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:25

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Andy Warhol life dates on flowers

July 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:21

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Shadow and manhole

spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:31

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Flopped horseshoe crab and RJ

summer 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:28

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A roaming studio

Johnson’s first photography studios were the driveway and back steps of his house, but soon he was carrying a pocket-size camera on his daily outings to nearby beaches, parks, and cemeteries. In spring 1992, he threaded a cutout silhouette of Joseph Cornell over the cord of a payphone, then photographed it with one hand while holding the receiver with the other—acting as operator of a hotline to the collage-art pioneer.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Path of headshots and back steps

spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:29

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Joseph Cornell silhouette and payphone

spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:36

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Bills, Stehli Beach

summer 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:11

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

One-legged figure beside back steps

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

One-legged figure beside back steps

spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:119

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Framing ideas

Even in his photography, Johnson exhibits a collagist’s instinct for insertion and layering. Most of his photographs are centered on objects that he placed between himself and a scene as he found it. On occasion, though, he used the camera in a conventional way, simply collecting views of sights that drew his interest, such as a billboard advertising nothing or the word HELP on the underside of a boat. Photographs such as these are the field notes of a minutely attentive observer

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Mondrian's grave and playing card, Mount Lebanon Cemetery, Queens

spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:133

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Billboard

summer 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:27

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Palm frond on sand

winter 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:10

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Hand, pier ruins, and Long Island Sound

23 August 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:93

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

HELP and shadow on underside of boat

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

HELP and shadow on underside of boat

spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:37

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Cactus in greenhouse

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Cactus in greenhouse

June 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:91

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Outdoor Movie Show in RJ's backyard

The photographs Johnson made between January 1992 and December 1994 feature several dozen collages in a large, vertical format he had never used before. He referred to these works as Movie Stars (or Move Stars), writing that “if the wind didn’t knock them down,” he planned to cast them in a “Ray Johnson Outdoor Movie Show,” lined up like dancers in a musical revue. In the end, still photography was the nearest he came to filmmaking.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Outdoor Movie Show in RJ's backyard

1 June 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:142

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Headshots through windshield, RJ and camera in rearview mirror

Were the Movie Stars made to be photographed? Or are the photographs mere documents of the Movie Stars? Perhaps the two bodies of work are best understood as complementary parts of a continuous creative cycle. Many of the Movie Stars are made on cardboard that bears photographic product information, suggesting that it was scavenged from the dumpster of the shop where Johnson bought his cameras and turned them in for developing.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Headshots through windshield, RJ and camera in rearview mirror

June 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum, gifts of the Ray Johnson Estate,

courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:145

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

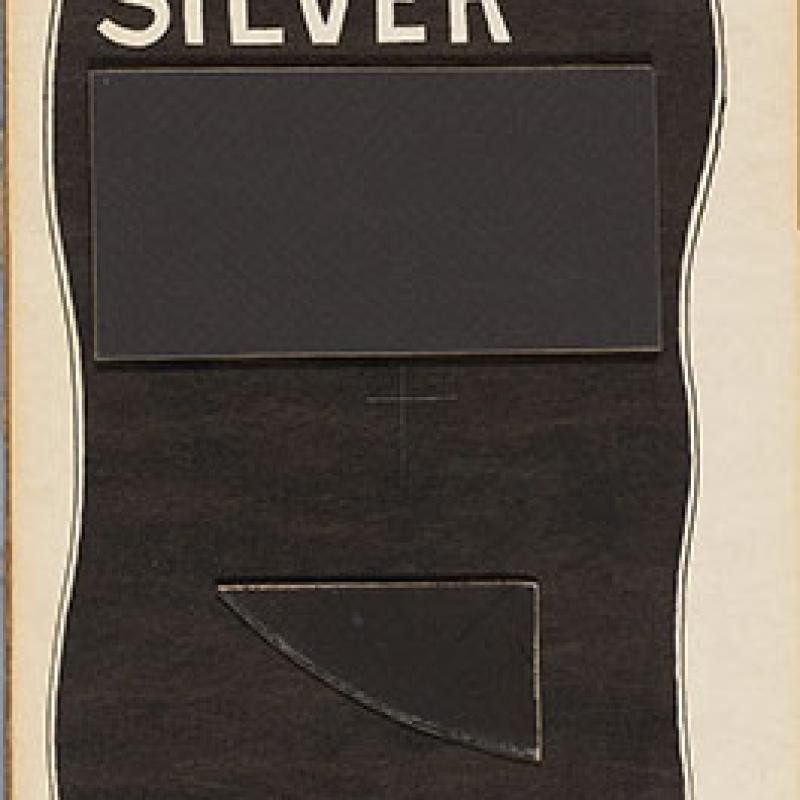

Movie Stars 1

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (LONG DONG SILVER)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

26 × 8 1/2 in. (66.04 × 21.59 cm)

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (EAR MUFS)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

31 1/2 × 8 1/2 in. (80.01 × 21.59 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty.

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (six blue Rays in Rolls)

Undated

Collage on corrugated cardboard

21 × 8 1/2 in. (53.34 × 21.59 cm)

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE, ONLY YOU)

1994

Collage on corrugated cardboard

32 × 7 1/2 in. (81.28 × 19.05 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty.

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

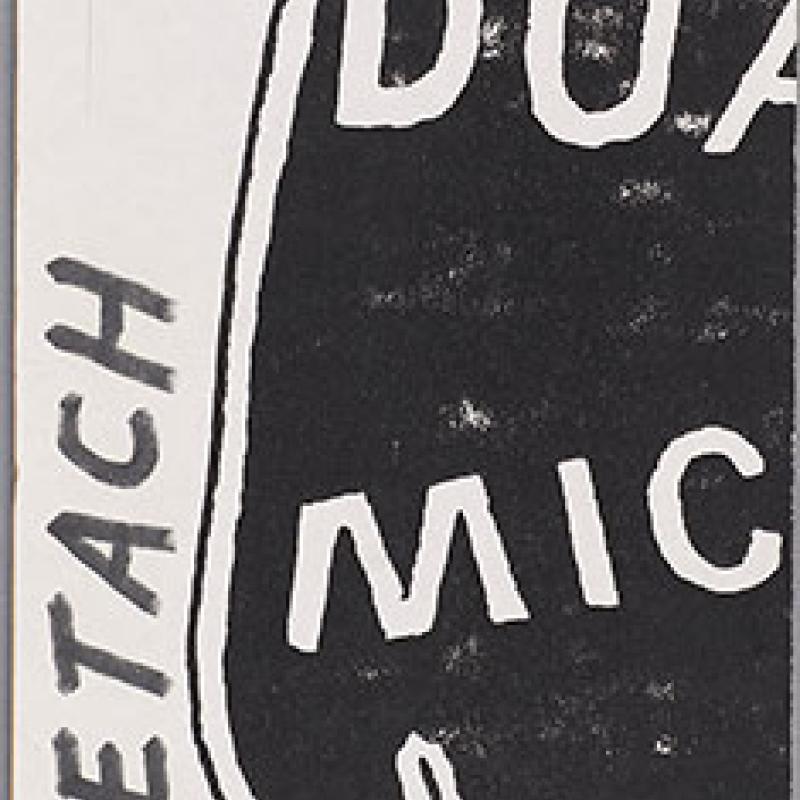

Movie Stars 2

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (detach DUANE MICHALS bunny)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

13 3/4 × 4 in. (34.93 × 10.16 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty.

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (yellow DUANE MICHALS bunny)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

13 3/4 × 4 1/2 in. (34.93 × 11.43 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty.

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Merkin Bunny)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

15 × 7 1/2 in. (38.1 × 19.05 cm)

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (JOSEF ALBERS with cat)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

17 3/8 × 7 1/2 in. (44.13 × 19.05 cm)

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Movie Stars 3

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (SIMONE SIMONE SIMONE with Joseph Cornell and Balanced Boulder)

1994

Collage on corrugated cardboard

31 1/2 × 8 in. (80.01 × 20.32 cm)

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (CAMP BELL SOUP, OTTO THEATRE)

1994

Collage on corrugated cardboard

31 1/2 × 8 1/2 in. (80.01 × 21.59 cm)

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (RAY JOHNSON COLLAGES ONE MILLION DOLLARS EACH)

1994

Collage on corrugated cardboard

31 5/8 × 8 in. (80.33 × 20.32 cm)

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Andy Warhol's Before and After with RJ as the noses)

1994

Collage on corrugated cardboard

31 1/2 × 8 1/2 in. (80.01 × 21.59 cm)

Camera and action

The Movie Stars feature a roll call of celebrity faces and names that is, in composite, unique to Johnson’s imagination. By photographing the collages, Johnson animated his personal pantheon in the familiar settings of his daily life. Composers Erik Satie and John Cage rest in the arms of a statue of Orpheus, the prophetic music-maker of Greek myth. Artist Jasper Johns punningly marks the door of an outhouse-like wooden structure. Johnson himself rides shotgun in his Volkswagen Golf while Elvis takes the wheel. And art critic David Bourdon and rock star David Bowie (embodiments, in different ways, of Pop’s legacy) join Johnson at the grave of “Wig art.” Once Johnson even photographed the Movie Stars in their staging area at home, ready to be loaded into the car and taken out for a day’s work.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Cage and Satie with Orpheus and Eurydice,

Planting Fields Arboretum

February 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:17

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Jasper John

February 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:4

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

WIGART grave and Movie Star of RJ between David Bs

April 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:159

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Movie Star storage in the house

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Movie Star storage in the house

14 December 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:71

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Out and about

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Headshot and Elvises in RJ's car

February 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:18

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Outdoor Movie Show on dumpster

18 May 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:141

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Four Movie Stars, Locust Valley Cemetery

31 March 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:59

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Crane figure at Piano Exchange window,

Glen Cove

winter 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:39

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Silhouette version of RJ portrait by Joan Harrison, Lattingtown Beach

To create this picture-within-a-picture, Johnson returned to the site of a much-reproduced portrait of him that photographer Joan Harrison made in the early 1980s. In the spot where he once sat, knees raised and arms outstretched, Johnson leaned a card that features a black silhouette of his symmetrical pose. As so often occurs in his photographs, Johnson here strikes an unsettling balance between absence and presence, erasure and memorialization.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Silhouette version of RJ portrait by Joan Harrison, Lattingtown Beach

autumn 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of

Frances Beatty; 2022.2:44

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Bill and Long Island Sound

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Bill and Long Island Sound

winter 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of

Frances Beatty; 2022.2:7

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Twins 1

In his writing and visual art, Johnson used juxtapositions and puns to suggest that nothing stands alone: everything finds correspondence in something else. Photography’s optical literalness gave him new ways to explore reality’s doubleness. Twins—and photocopied photographs—are nearly alike yet insistently distinct. Mirrors give back a faithful, yet laterally reversed, image of nature. The shadow of a thing echoes its original, but (like a moticos) it is flat and empty of internal detail.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Twins

22 November 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:103

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

RJ reflected in ice truck and split Duane Michals Movie Star

11 May 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:140

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Max Ernst bunny, chair, and mirror

7 October 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:99

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Back steps and moticos

spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:32

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Twins 2

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Moticos and shadows in the house

10 October 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:100

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

CAMP BELL SOUP at NOON, Saint Patrick Cemetery, Upper Brookville

18 September 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:98

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New YorkHand, pier ruins,

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Shadow and Lee Friedlander book

winter 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:15

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Bunnies

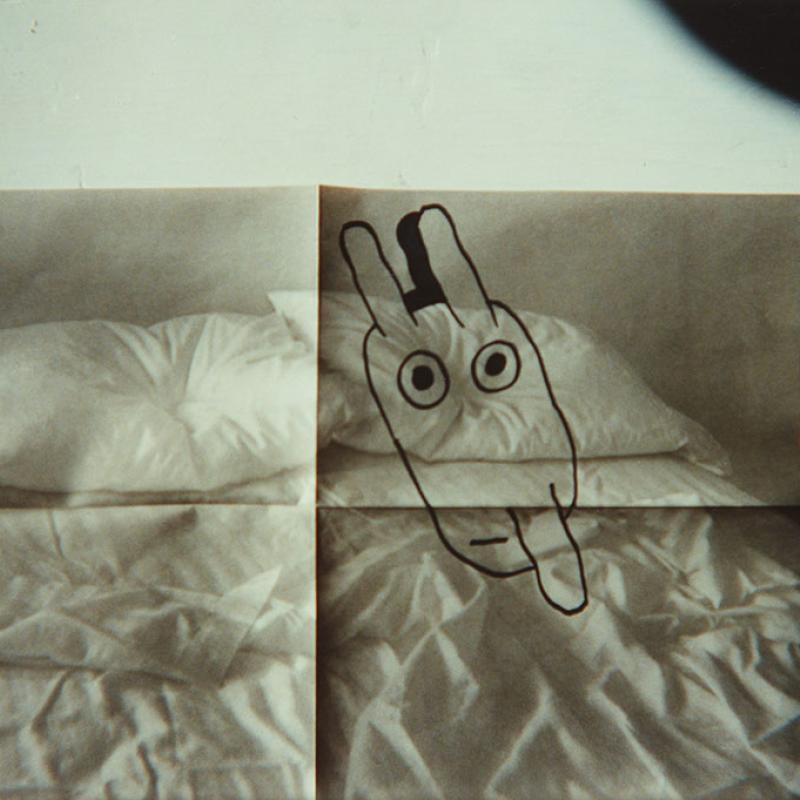

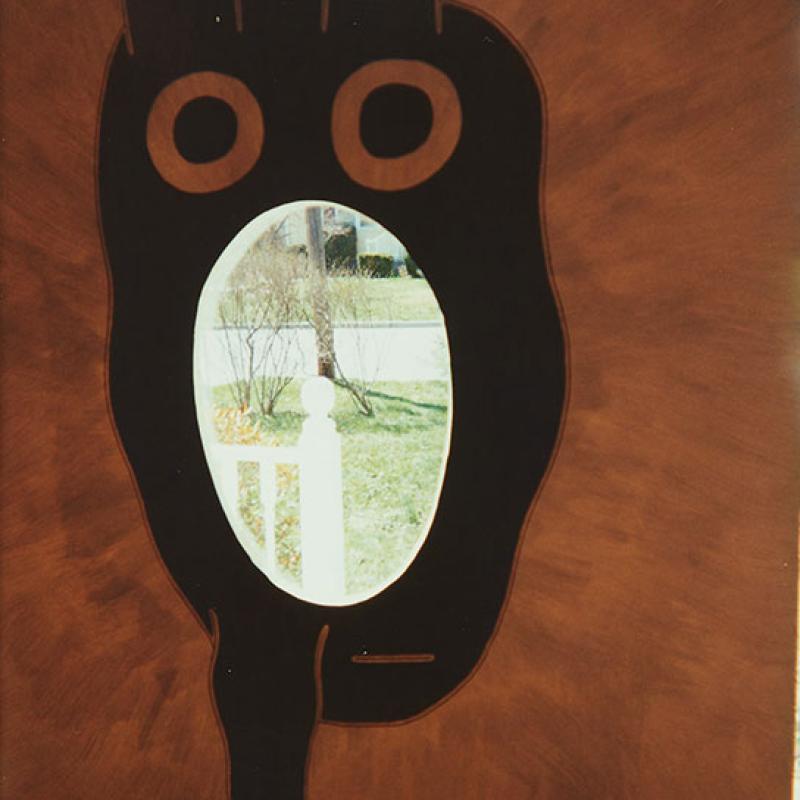

A round-eyed, long-nosed bunny head functioned as Johnson’s signature and, as he said, “a kind of self-portrait.” Despite the bunny’s blank expression, context can render it comical, hapless, sinister, or obscene. Johnson altered Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s photograph of a rumpled empty bed—an iconic image of gay mourning during the AIDS crisis—by resting a lone bunny’s head on one of the two pillows. Johnson cut a face-sized hole out of one bunny, then photographed the view outside his front window through the gap. He gave the same bunny to passersby to wear and, once, laid it suggestively atop his toilet bowl. When a large old tree next door was being chainsawed apart, Johnson found in its branching form a gaunt, eyeless bunny’s face.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Bunny drawn on Felix Gonzalez-Torres's

"Untitled"

2 January 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:72

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Long Dong Silver, Lattingtown Beach

16 November 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:67

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Half bunny on manhole cover

summer 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:120

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Six Movie Stars in RJ's car

April 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:63

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Rabbit Hole

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Cutout bunny and view of front yard

19 April 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:87

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Flopped stranger wearing cutout bunny

spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:34

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Cutout bunny and toilet in the house

30 October 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:132

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Bunny tree in backyard

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Bunny tree in backyard

7 April 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:62

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photographs into collages

What did Johnson intend to do with the thousands of photographs he made between 1992 and 1994? There are few solid indications. He mailed some to correspondents, either in the form of original prints or as photocopies. He also incorporated a handful of his photographs into collages that differ markedly in scale and sensibility from the larger, contemporaneous Movie Stars. In one collage, a photograph of five Movie Stars—arranged like sequential ads beside a road—is punningly combined with a bunny head bearing the name of abstract painter Ad Reinhardt (1913–1967), a friend and employer of Johnson’s in his early New York years.

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (red bunny NOTHING)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

12 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (31.75 × 19.05 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum,

gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.5:2

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

Untitled (Ad Rein Hardt Bunny)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

12 1/2 × 7 5/8 in. (31.75 × 19.37 cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.5:1

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

RJ with PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE and camera in mirror

This self-portrait appears on a roll of film Johnson turned in for developing about three weeks before his suicide by drowning on 13 January 1995. The flopped lettering on the Movie Star in his hand undergoes a further reversal in the mirror. On a literal level, the words “REAL LIFE” refer to the New York–based art magazine REALLIFE (1979–94), which Johnson hoped would soon publish an article about his yearslong collaboration with a friend, Sheila Sporer. But the message unmistakably announces, too, that the artist was soon to venture beyond the reach of “real life.”

Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

RJ with PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE and camera in mirror

23 December 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of

Frances Beatty 2022.2:106

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York